In order to truly appreciate the magnitude of the student strike, it is important to consider the long-term social history which made it possible.To be more precise, they protested against two of the least-recognized but massively important effects of the long colonial era which ran from 1492 until 1945, namely colonial carbon and colonial demography – writes Dennis Redmond.

There is an old saying (incorrectly attributed to Auguste Comte) that demographics is destiny. On Friday, March 15, the first global student strike in world history turned destiny into demographics.

An estimated 1.5 million young people, in two thousand locations and 125 countries across the planet, left their classrooms to protest against climate change caused by the burning of oil, coal and gas. More precisely, they were protesting against the lack of serious action by the world’s political and economic elites to stop climate change. While many of the student strikers marched in the high-income nations, there were plenty who marched in middle-income and low-income nations:

The strike began with a single individual who had the courage to stop doing what the world’s elites were doing — namely, almost nothing. This individual was Greta Thunberg, an ordinary 15-year-old Swedish high school student who decided to do something extraordinary. On August 20, 2018, she sat down in front of Stockholm’s parliament building as her very own one-person protest.

At the time, nobody took her seriously, including her parents. But she was entirely serious. Like any good student, she had diligently researched the topic, and learned that the world’s climate scientists agreed on one simple truth. This truth is that we human beings must end our carbon emissions, or else climate change will destroy all human life on our planet.

So Thunberg kept coming back to protest every Friday, until a passing reporter noticed her and filed a story. The news spread across the world’s digital media networks like wildfire, inspiring individuals to start their own student strikes elsewhere. A few students went on strike in the Netherlands on September 4, a few in Germany on September 14, and a few in Canada on November 2. And then everything snowballed, all at once. The tens turned into hundreds, and then thousands, and then millions.

Yet the importance of the climate strike is much bigger than a list of cities and numbers. The strikers are one of the first mass movements to draw on two of the least-understood but most influential legacies of the long colonial era which ran from 1492 until 1945. These two legacies are colonial carbon and colonial demography — a.k.a. how empires burned fuel, and how empires produced people.1

The colonial carbon story is simple. The nations which had the biggest colonial empires also burned most of the fossil fuels causing climate change. According to the best estimates of climate scientists, about 70% of humanity’s total carbon emissions since the beginning of industrialization occurred between 1751 and 2002, and the remaining 30% between 2003 and 2017. The World Resources Institute estimated that the United States (a colonial empire until 1945) was responsible for 29.3% of carbon dioxide generated by human beings between 1850 and 2002.

This is slightly greater than the countries of the European Union (a.k.a. the polity created by the heartlands of the former Austrian, Belgian, British, Dutch, French, German, Italian, Portuguese and Spanish empires), which generated 26.5% of all emissions during the same period. The figure for Russia (the former heartland of the Romanov colonial empire and the Soviet neocolonial empire) is 8.1%, while the figure for Japan (an empire until 1945) is 4.1%. Add them all up, and the former empires were responsible for 68% of all carbon dioxide emissions until 2002, as compared to only 7.5% for China and only 2.2% for India.

It is true that China and India industrialized rapidly between 2003 and 2017, which is why they are now the largest and fourth-largest emitters of carbon, respectively. That said, their emissions in per capita terms are much lower than those of the US and EU. In fact, the nations which were formerly colonial empires still account for about one-third of the 36.15 billion tonnes of CO2 human beings sent into the atmosphere in 2017:

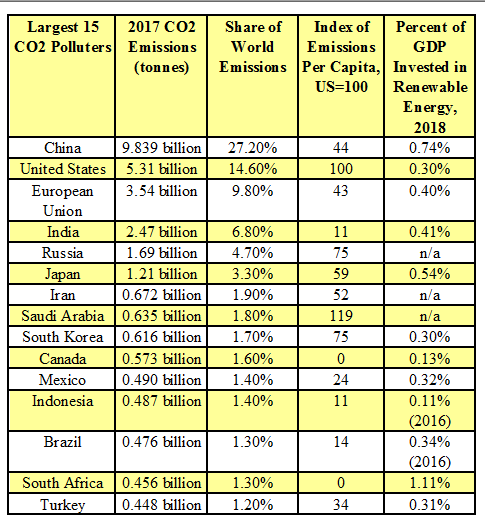

Table 1. Largest 15 CO2 Polluters, 2017. Emission data is from Global Carbon Atlas and renewable investment data is from Bloomberg BNEF.

Shockingly, the polities most responsible for carbon colonialism (e.g. the US at 0.30% and the EU at 0.40%) spent less on renewable energy as a percent of their total economies in 2018 than China (0.74%) or India (0.41%), despite being vastly richer than the latter (Japan’s figure of 0.54% is the shining exception to this dismal rule).

To be sure, colonial carbon is much more than just a history of predation. It is also a history of the resistance to that predation, a.k.a. the global climate justice movement. The history of this latter can be traced all the way back to Karl Marx, who famously began his career as a radical journalist defending the rights of German peasants to gather fallen firewood in manorial forests. Conversely, the same British miners who produced the coal enabling the British navy to rule the world’s oceans also organized the Chartist uprisings of the 1840s and some of Britain’s most militant unions during the 1880s. More ambiguously, the anti-colonial revolutionary movements of the 1960s and 1970s sought to nationalize coal and oil resources to benefit the public (albeit with deeply problematic results).2

While these past resistances had their weaknesses and limitations, they did make today’s climate justice movement possible. One of the most famous examples is the 2016 Standing Rock Sioux campaign against the DAPL oil pipeline, which synthesized centuries of indigenous American resistance against 19th century colonial genocide and 20th century oil barons, thereby inspiring a whole generation of contemporary activists. Beginning in 2017, the climate justice movement began to assert significant electoral power, forcing many US states and EU government to shut down coal plants and invest heavily in solar and wind power.

While a number of the student strikers knew about the climate justice movement, and a few of them might have participated in its campaigns, this does not fully explain why millions of young people suddenly took to the streets.

This is where colonial demography enters the picture. Between 1492 and 1945, colonialism generated massive economic inequality — a few imperial polities got rich, while entire continents were impoverished. Colonialism also created gargantuan levels of political inequality, i.e. a few imperial polities developed democracy, whereas all colonial regimes remained despotic.

More subtly, colonialism generated titanic levels of demographic inequality. The three-stage demographic transition typical of industrialization — an initial population boom, a subsequent slowdown, and eventual stabilization — occurred first in the imperial nations, and spread to the colonized regions a century later.3 This history means the middle-income and low-income nations of the world, who are the least responsible for carbon colonialism but who will suffer the most damage from climate change, now have the largest youth populations.

In 2018, the total number of human beings under the age of 20 reached 2.567 billion, or 33.4% of the planetary population of 7.7 billion. The main participants of the school strike have been the oldest and most mature section of this group, namely 15 to 19 year-olds, a subsection which numbers about 600 million. According to the 2017 United Nations world population estimates, about half of these 600 million young people live in Africa and India, and nine out of ten live in the industrializing nations. Conversely, only 60 million — one in ten — live in the fully industrialized nations.

What makes these 600 million so important is that they are the most digitally savvy group of people on the planet. Teenagers have long been regarded as the single most valuable test market by the world’s advertising, media and cultural industries, due to their status as the “early adopters” of consumer goods and technology. Whatever transnational capitalism is selling — TV shows, videogames, clothing, smartphones — is always tested first on teenagers, and only later released for general consumption.

That said, these same teenagers also experience one of the most explosive aspects of plutocratic capitalism: the continuous intensification of competition by those least able to sustain such. The public funding of education has been systematically cut almost everywhere on the planet, driving parents to send their children to private schools which charge sky-high fees. Students are also being subject to escalating levels of social pressure to excel at standardized national tests (this is especially true for China’s youth). Many teenagers have highly educated older family relatives who cannot find jobs at all, and who survive in the underground economy or by emigrating.

On March 15, a million and a half teenagers (plus an unknown number who followed the protests online) transformed themselves from objects of plutocratic capitalism into potential subjects. Their immense numbers, when combined with their sophisticated digital media skills, means this was quite possibly the single most powerful coordinated protest ever conducted by young people in world history.

One of the first achievements of this protest has been the sudden and dramatic popularization of a new discursive frame to talk about climate change. Whereas the 1960s were all about decolonization, and the 1990s were all about democratization, the student strike has made it clear the 2020s are going to be all about decarbonization — a.k.a. the complete cessation of fossil fuel emissions between 2020 and 2030, or what can be called Carbon Zero.

Carbon Zero will require massive investments in renewable energy in every country on the planet, the replacement of all hydrocarbon-powered vehicles by electric ones (literally everything from automobiles to marine supertankers), biofuels for jet planes, and the mitigation of past carbon emissions via the regrowth of rainforests and mangrove wetlands.

Less than two weeks after the March 15 strike, researchers at the Rainforest Action Network gave Carbon Zero its first target: some of the biggest banks in the world have been financing humanity’s extinction, by pouring $1.9 trillion into the fossil fuels industry between 2016-2018. As for what role the student strike will play in energizing Carbon Zero, that is a subject for our next article.

Notes:

1. The original idea of carbon colonialism can be credited to Anil Agarwal and Sunita Narain, who wrote a famous article in 1991 denouncing a UN report which blamed climate change on the industrializing world instead of on the rich countries as environmental colonialism.

2. There is a cruel irony in the fact that these nationalizations turned horribly toxic when postcolonial elites plundered the energy-rents of these resources as ruthlessly as the former colonists, or else used them to wage wars of imperial aggression as horrible as anything in the annals of colonialism, e.g. Saudi Arabia’s criminal war against Yemen or Russia’s monstrous imperialist war against Ukraine.

3. The initial population boom of the postcolonial and newly-industrializing nations took place between 1945 and 1985, roughly a century after the initial population boom of the imperial nations. This doubled the world population from 2.5 billion in 1950 to 5 billion in 1987. After 1987, the industrializing nations entered the second stage of their demographic transition, about seventy years after the fully industrialized nations. Fertility rates dropped sharply, reducing world population growth from a peak of 2.12% per annum in 1969 down to 1.78% in 1987 and then to 1.24% by 2008. After 2008, industrializing nations entered the third stage of transition, namely stabilization, about fifty years after the fully industrialized nations. The latest UN projections show the long-term world population will stabilize at around 10 billion.

Feature image: Photo from Thailand by Biel Calderon, courtesy Greenpeace.

Dennis Redmond is an independent scholar of digital media, videogames and transnational media.