The Occupy movement led to a sort of reinvention of the American left. To understand how and why Occupy made this possible, it is worth reflecting on the unique political history of the United States during its sixty-three years of world hegemony (1945-2008) – writes Dennis Redmond.

Part 1 of this series can be read here.

The great mass uprisings of 2011, most notably Arab Spring and Occupy, were a glorious beginning. They mobilized societies which had seemed impossible to mobilize, due to virulent state repression (the Presidential monarchies of northern Africa and southwestern Eurasia) or untrammeled consumerism (the US). They generated a slew of remarkable media innovations, ranging from the social media sites and chatrooms which supported the Egyptian, Tunisian and Libyan revolutions to the livestreams and citizen journalism websites which chronicled Occupy’s encampments.

Yet their true historical importance is not that they succeeded in any way to bring about change. In fact, most of the protests achieved none of their goals, not even the basic one of more accountable governance.1 This does not mean they were failures. What it means is that their greatest contribution was to make change thinkable.

They did this by garnering a wave of sympathy and mass support from ordinary citizens across the world. This support was visible everywhere from the sudden popularity of news channels such as Al-Jazeera, to the crowds which filled up hundreds of city squares for days on end. It was embodied in slogans such as “We are the 99%” and “The people demand the fall of the regime”.

One of the most important results of this wave of support was the reinvention of the American Left. In 2013 and 2014, young people began to rebel against their plutocratic elites on a scale with no parallel in recent American history. Tens of thousands of these young people participated in the Black Lives Matter campaign against policies of mass incarceration, and then went on to transform the 2016 Bernie Sanders primary campaign into a major political force. In 2017, those young people marched in the biggest pro-immigrant and anti-kleptocracy protests in modern American history. In the summer of 2018, they ran as openly progressive candidates and won primary elections all across America.

Young women of color suchas Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez are reinventing the American Left. Photo by Brandon Jordan, courtesy Queens County Politics.

To understand how and why Occupy made all of this possible, it is worth reflecting on the unique political history of the United States during its sixty-three years of world hegemony (1945-2008).

Since 1945, all progressive movements in the United States have struggled against two powerful barriers. The first barrier was the incomparable power and wealth of the US economy during the second half of the 20th century – or more precisely, the imperial surplus distributed to ordinary US citizens. The second was the uniquely atavistic nature of the US political system – or more precisely, the ways in which US hegemony endowed fundamentally obsolete political institutions with unnatural longevity.

Let’s start with the imperial surplus. Between 1945 and 1973, real wages rose steadily for almost all Americans thanks to massive military spending (10% percent of the US economy was military-related during the 1950s, and 8% during the 1960s), Great Society programs like Medicare and Medicaid, and strong unions (about a third of the US workforce was a member of a labor union in 1950).

This exceptional wealth generated an equally exceptional political consciousness, one saturated with consumerism. US citizens had the highest real wages in the world, which meant ordinary workers could afford cars, homes and consumer goods the rest of the planet could only dream of. Given this extraordinary prosperity, it is not surprising the United States never developed the sort of labor-based, socialist or communist parties which played a prominent political role in post-1945 Britain, France, Italy, Japan and other Western European democracies. Small versions of these parties did exist in America, but they never became popular.

That said, the United States did develop a lively politics of dissent. This politics was rooted primarily in the experience of social groups excluded from the imperial surplus. It took the form of what sociologists call the micropolitics or identity-politics – a.k.a. the politics of the distribution and consumption of the imperial surplus.

One of the most famous and successful examples of this post-1945 identity-politics was the African American civil rights movement. The US had the highest real wages in the world in the 1950s, but the one in ten Americans who were African American suffered from vicious segregation, low-wage employment, and atrocious police violence. In the words of the 2018 US Civil Rights Commission report:

At the beginning of the civil rights movement and with more aggressive litigation, black registration rates increased by 6 percentage points from 1947 to 1950 across the South—yet by the mid-1950s, 75 percent of African Americans were not registered to vote. The registration rate of black citizens in Mississippi was still less than 5 percent, and in states like Arkansas, Florida, Louisiana, and Texas, it was about one third.

The ingenious response of the civil rights movement was to leverage the margins to move the mainstream, by launching mass struggles for racial equality inside the key superstructures of US society. These superstructures ranged from those of consumption (the consumer-led campaigns to desegregate shops and small businesses) to those of local governance (campaigns for African American voting rights), and from regional transportation networks (Rosa Parkes’ historic bus protest and the later Montgomery bus boycott) to mass media networks (the performances of Afro-Caribbean diasporic stars such as Harry Belafonte, as well as the creation of modern rock music by African American artists such as Chuck Berry and Jimi Hendrix).

It should be emphasized that none of these movements rejected class politics per se. Nor were they a distraction from some more authentic or radical project of working-class resistance. Rather, they were a clever and necessary tactical adaptation by American workers to the political deep freeze of Cold War America. This was an epoch when the most violent forms of racial terror and sexual violence were rampant, when McCarthyism crushed most forms of open political dissent, and when most labor unions focused on higher wages rather than building community coalitions.

The identity-politics movements responded to this onslaught by repackaging worker self-organization as community mobilization. For example, the environmental movement constructed coalitions of home-owners, nature enthusiasts and environmental scientists to win landmark anti-pollution legislation. The counter-culture of the 1960s built its own musical infrastructure of music festivals, community gatherings and road caravans, anticipating many of the features of the independent digital music and videogame cultures of later eras. The feminist movement politicized the infrastructures of gender, using the insight that “the personal is the political” to mobilize Americans against all aspects of misogyny in US society. In the wake of the landmark Stonewall protests, the American LGBTQ movement politicized the infrastructures of sexuality, inaugurating mass struggles against homophobia and heteronormativity. Finally, the anti-Vietnam War protesters of the 1960s created a wide range of informal institutions and local spaces where new types of anti-colonial solidarity movements could crystallize.

Radical movements flourished in Oakland and Berkeley, California in the 1960s. Photos courtesy Hoffman/Barb, Grover Wickersham/LNS. The Berkeley Revolution: A digital archive of one city’s transformation in the late 1960s & 1970s

Collectively, these movements achieved remarkable improvements in the lives of ordinary Americans over the second half of the 20th century. Environmental laws made the air more breathable and water more potable; brain-rotting lead compounds were banned from gasoline and paint while ozone-destroying chlorofluorocarbons were eliminated from refrigerants; African Americans won full voting rights; women entered the professional workforce in significant numbers; the LGTBQ community fought for and won partnership benefits and mass acceptance; US soldiers left Vietnam; racist immigration quotas were overturned, and so forth.

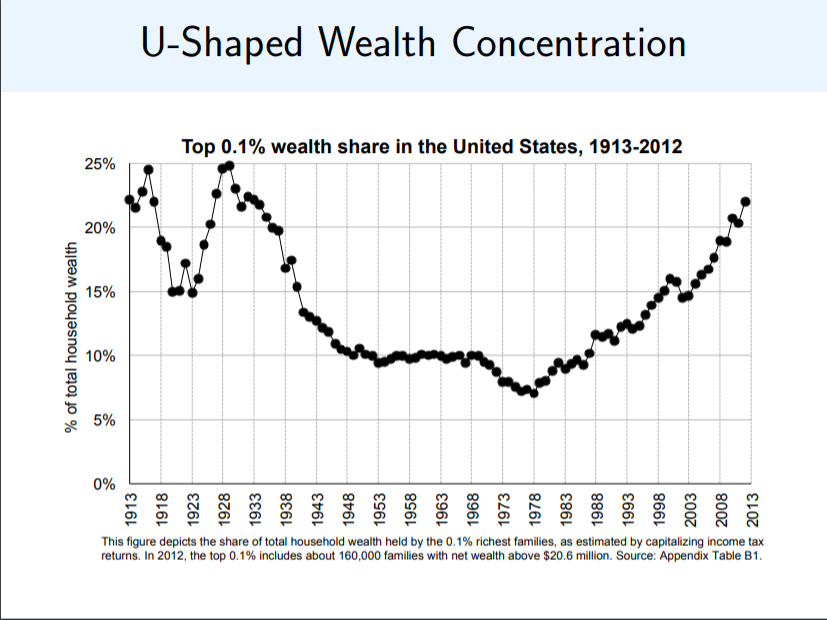

It is true that the limits of these victories were those of the American imperial surplus. This became a problem after 1973, when the economic elites of the United States began to take more and more of that surplus for themselves, leaving less and less for everyone else.

In most societies, this ripping up of the social contract would trigger a political firestorm. So why didn’t ordinary Americans protest? They did indeed protest, but their protest was overwhelmingly canalized and channeled by the post-1973 populist Right, not by a revitalized Left.

There were two main reasons for this canalization. First, rising levels of debt replaced rising wages as the main engine of US mass prosperity. Between 1973 and 2008, students took out more and more education loan debt, thinking the value of their degree would keep going up. Home-owners took out more and more mortgage debt, thinking the value of their property would keep rising every year, enabling them to sell at a profit and buy an even bigger home (people who did this were called “equity emigres”). Wall Street banks took out more and more debt, thinking the value of the securities signified by that debt would keep increasing. And so the theoretical values of degrees, homes and securities increased – until they didn’t. While the debt bubble lasted, though, most debtors were too busy purchasing consumer goods or scrambling to make their next payment to worry about politics.

After 1973, plutocracy ran riot in the United States. Data from Emmanuel Saez.

The second reason for the success of the populist Right is that second barrier we mentioned previously. This barrier is the extreme atavism of America’s political institutions.

While the US produces some of the most advanced technology on the world, it remains the world’s last 18th century constitutional oligarchy, with a shamelessly corrupt political system beholden to wealthy elites rather than voters. Its first-past-the-post electoral system makes it almost impossible to create independent political parties outside the prevailing duopoly; its president is selected by an outrageously undemocratic electoral college, which enabled the candidate with fewer popular votes to become President in 2000 and again in 2016; its senate gives Wyoming and California two senators apiece, even though Wyoming has only 0.6 million citizens and California has 39.5 million; and its congressional districts suffer from rampant gerrymandering.

This is in shocking contrast to the parliamentary democracies of all other fully industrialized nations. In fact, most contemporary middle-income nations have democratic polities more functional than that of the United States. For example, Mexico, the southern neighbor of the United States, junked its one-party state in the 1990s and adopted a modern electoral system of modified proportional representation.

Yet the atavism of US electoral institutions cannot be explained away as a case of poor decision-making or historical inertia. It existed because powerful forces want it to exist. These forces included the plutocratic elites who own the US economy, of course, but they also included ordinary Americans corrupted by the imperial surplus.

The single most powerful form of this corruption – and the real reason for the atavism of US politics – was imperial white nationalism. It is easy to forget just how xenophobic, racist and exclusionary American society was prior to the identity-politics movements of the 1950s and 1960s. During the 1920s, vicious discrimination was practiced against Jews, Catholics, Asian Americans and Latinx Americans, while African American communities suffered open terror from white extremist groups. Joshua Rothman notes that membership in the white terrorist organization, the Klu Klux Klan, hovered between 2 to 5 million in the mid-1920s – roughly 2% to 5% of the entire American population.

This vast reservoir of imperial racism did not disappear during the mass mobilizations of the New Deal and World War II, but was restructured into a consumer-based imperial whiteness. Rising US real incomes between 1945-1973 were the literal and figurative wages of this imperial whiteness, which is one of the reasons why the US Federal state unleashed unprecedented levels of open violence on the Black Panthers between 1968 and 1971.2 The Panthers were among the few dissident groups to emphasize that imperial whiteness was not some minor blemish or defect of the US imperial polity. Rather, it was its most central and constitutive feature. The everyday violence it unleashed on the bodies of US citizens of color was the flip side of the US military interventions against Third World anti-colonial revolutions.

Conversely, the 1973-2008 debt bubble signified the financialization of imperial white nationalism, in much the same way that the IMF structural adjustment packages of the 1990s represented the financialization of the Cold War military intervention. The effects of this financialized white nationalism on the American people have been catastrophic. After the end of Jim Crow (a.k.a. legal segragation) and most overt forms of racial discrimination, this reconfigured white nationalism legitimated the post-1973 mass incarceration of communities of color and the poor by means of the war on drugs (what Michelle Alexander called the new Jim Crow). The achievement of full voting rights for Americans in the late 1960s was sabotaged by taking away the voting rights of convicted felons, by making it difficult for poor Americans to register to vote, and by making it legal for corporations to purchase politicians like so many head of cattle. When the segregation of schools was finally ended in the 1950s, white nationalism responded by slashing government funding for all levels of public education. When racist immigration quotas were abolished in 1965, white nationalism responded by endless campaigns to demonize and deport nonwhite immigrants.

It was the combination of a debt-fueled imperial surplus, plus the rabid revanchism of financialized imperial whiteness – an empire of debt yoked to an empire of whiteness – that made the populist Right the driving force of US politics after 1973.

Conversely, what made Occupy so important is that it was the first progressive mass movement to make this collusion visible. Before Occupy, most Americans could not grasp the collusion between the imperial surplus and imperial whiteness. After Occupy, ordinary Americans started to see – and spontaneously resist – this collusion all around them. This spontaneous resistance was most evident among America’s youth, who are the heaviest and most skilled users of today’s digital technologies. As for the story of how young Americans are using digital tools to reinvent American Leftism, that requires another essay.

Endnotes

- The largest six Arab Spring uprisings of 2011, namely those of Bahrain, Libya, Egypt, Syria, Tunisia and Yemen, all had a common political root in the legitimation crisis of Presidential monarchies which failed to deliver employment to the swelling youth population of the Arab cities. All six uprisings also mobilized their respective populations through digital media and digitally-inflected strategies of mass participation. While Tunisia made a peaceful transition to full electoral democracy, the economic crisis of its remittance-fueled and tourist-dependent economy was not addressed by subsequent governments. Meanwhile, forms of semi-praetorian rule were imposed on Bahrain and Egypt, militia rule was imposed on Libya, and Syria and Yemen devolved into sectarian and ethnic civil wars.

- “The federal government and local police forces across the nation responded to the [Black] Panthers with an unparalleled campaign of repression and vilification. They fed defamatory stories to the press. They wiretapped Panther offices around the country. They hired dozens of informants to infiltrate Panther chapters. Often, they put aside all pretense and simply raided Panther establishments, guns blazing. In one case, in Chicago in December 1969, equipped with an informant’s map of the apartment, police and federal agents assassinated a prominent Panther leader in his bed while he slept, shooting him in the head at point-blank range……Federal agents sought ‘to create factionalism’ among Party leaders and between the Panthers and other black political organizations. FBI operatives forged documents and paid provocateurs to promote violent conflicts between Black Panther leaders—as well as between the Party and other black nationalist organizations—and congratulated themselves when these conflicts yielded the killing of Panthers. And COINTELPRO sought to lead the Party into unsupportable action, ‘creating opposition to the BPP on the part of the majority of the residents of the ghetto areas.’ For example, agent provocateurs on the government payroll supplied explosives to Panther members and sought to incite them to blow up public buildings, and they promoted kangaroo courts encouraging Panther members to torture suspected informants.” Joshua Bloom and Waldo E. Martin, Jr. Black against Empire: The History and Politics of the Black Panther Party. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2013 (5-6).

Dennis Redmond is an independent scholar of digital media, videogames and transnational media.