The crisis of tea gardens in north Bengal go far deeper than only locked- out gardens and starvation deaths. These are but only one part of the complex web of problems plaguing the industry. Non-payment, or rather non-existence, of minimum wages being only one of them. The ongoing 3-day workers strike across the entire region for minimum wages, despite backlash and sabotage from the trade union wings of the ruling parties of both the Hills and the state, provides an opportunity to bring to the fore the structural crisis faced by the tea workers and the industry. Samik Chakraborty writes, from the Darjeeling hills.

One and half decades back, the City Center shopping mall was built over the ruins of Chandmoni Tea Garden. Two workers were shot dead to quell the huge protest opposing this destruction of the tea garden and eviction of garden workers to build a ‘satellite township’. On 7th August, hundreds of tea garden workers, were squatting in rows in front of that mall. They were coming down from tea gardens scattered over the Terai region bordering Bihar and Nepal, to Uttarkanya, the administrative headquarter for North Bengal, in a rally which was stopped in front of the mall by the police. On 7 August 2018, the police stopped numerous such rallies taken out by the tea workers from tea gardens across the Terai, the Darjeeling Hills and the Dooars regions, from entering Siliguri. But workers’ rallies still kept pouring into the streets, relentlessly. Police forces have been posted across the tea gardens. Venue of the meeting for tripartite talks on that very day, was changed three times within a span of a few hours, to confuse and mislead the garden workers and prevent them from assembling there. One km radius around the meeting location had been cordoned off by the police, blocking all roads.

“What’s the minimum wage for tea workers? Even that much is not paid?” – we often hear this question. Far away from the tea gardens, in Kolkata or other such places, this is how the question of minimum wage floats in the air. Even those who work on issues of workers’ rights, have such questions.

The answer is no, there is no minimum wage in the tea industry! It was never there.

Unlike in the case of other industries where the Government takes up the responsibility of determining minimum wages, the situation of tea workers of West Bengal (and Assam) has been different. Here every three years wages are fixed after Owners-Workers-Government tripartite negotiations. This time the workers want an end to this practice of perpetual uncertainty. From 2014 onwards, the tea workers of West Bengal have built up a struggle demanding minimum wage.

Around four and a half lakh workers working in the 278 tea estates (plus the lakhs of workers working in the numerous “New Gardens”) spread across the Darjeeling hills and Terai, parts of Kalimpong hills, and the vast Dooars region covering Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar districts, were eagerly looking forward to the decision of the Government this time. After many years of delaying tactic, this 6th August was the day when the minimum wage was finally supposed to be declared. Needless to say, the Government has failed these workers yet again.

Around four and a half lakh workers working in the 278 tea estates (plus the lakhs of workers working in the numerous “New Gardens”) spread across the Darjeeling hills and Terai, parts of Kalimpong hills, and the vast Dooars region covering Jalpaiguri and Alipurduar districts, were eagerly looking forward to the decision of the Government this time. After many years of delaying tactic, this 6th August was the day when the minimum wage was finally supposed to be declared. Needless to say, the Government has failed these workers yet again.

The proposal of a Rs 172 as daily wage that was placed at the meeting in the presence of the State Labour Secretary, was rejected unequivocally by representatives of the Joint Forum leading this struggle. An immediate sit in dharna was started after the negotiations failed. Late in the same night, together with threats of arresting the protestors, came a proposal from the Government that the meeting will be re-convened again the following day. The dharna was called off. But by then news had spread to the tea gardens across the entire region that the workers’ hopes and aspirations were being trampled in Uttarkanya. A 3-day strike was called in gardens across Terai-Dooars, and it was decided that ‘Made-Tea’ supply in the hills will be stopped.

From 7th morning the strike started in Terai-Dooars, and supply of tea leaves was stopped across the hills. The waves of strikes swelled on the 8th, only to intensify further on the third day on 9th. The Labour Secretary had unilaterally left the meeting on the 6th, announcing that a fresh meeting will be reconvened only on the 20th. But because of the pressure built by the successful and widespread workers strike, the Government preponed the determining meeting on the coming 13th. As of now, workers wait for that meeting.

“What would be the amount of the minimum wage? How much are the workers asking for?” There are many who want to know this.

Many owners have normalized the non-paying of PF, gratuity, etc. Though the responsibility of repairing roads inside the gardens rests with the owners, but lately even that has been relegated to NREGS. Post the Food Security Act of 2016, the owners also shed off their responsibility of providing ration supplies to the workers, though that ration is actually a component of the wage!

In this country there is this thing called the Minimum Wage Act of 1948. But the tea industries of Bengal and Assam had been kept outside of its purview. Whereas the gardens of Kerala and Tamil Nadu have already adopted minimum wages, in the gardens of the north ‘collective bargaining’ has been the procedure for determination of wage. Tea industry of West Bengal is regulated according to the Plantation Labour Act of 1951 and the WB Plantation Labour Rules of 1955. This led to the two-part wage system – a cash wage, plus the so-called ‘fringe benefits’. Since the location of these gardens mean just paying cash is not enough to ensure that workers would be able to procure necessary supplies easily, things like ration, medical needs, house repairing utilities, other requirements such as umbrellas, shoes, blankets, fuel wood or cash thereof, crèche facilities for children etc., are supposed to be provided under these ‘fringe benefits’. However, the supply of these ‘benefits’ have only waned over time, and at present they are altogether non-existent across many gardens. The arrear amounts due to the workers have consistently swelled. The Government has known all of this. The most detailed account of this situation can in fact be found in the Government’s own report of 2013. But still no measures were taken. Many owners have normalized the non-paying of PF, gratuity, etc. Though the responsibility of repairing roads inside the gardens rests with the owners, but lately even that has been relegated to NREGS. Post the implementation of Food Security Act in the gardens in 2016, the owners also shed off their responsibility of providing ration supplies to the workers, though that ration is actually a component of the wage! After dilly dallying for a couple of years, only recently it was announced that the cash equivalent of this ration will be added to the workers’ wages. But even that amount is shamefully low, at Rs 9 only. The Government’s own calculations suggested earlier that this figure should be at least Rs 26. Moreover, the ration allowance of Rs.9 (even if it is so!) was not paid over a period stretching from February 2016 to April 2018.

In the 2014 Wage agreement (which was signed finally only in 2015 because of the ongoing struggle for Minimum Wage), wage was fixed at Rs 112.50 for the first year, and was increased recently to Rs 132.50 after annual increments of Rs 10 every year. It was also decided then that this was the last such agreement, and Minimum Wage will be implemented from 2017 onwards. For this purpose, a Minimum Wage Advisory Committee was constituted following that agreement, in 2015. However, staying true to its policy of cuddling up with the owners, the Government had kept this Committee mostly in hibernation. Last March, the Government abruptly declared an interim wage of Rs 150. Together with the Rs 9 ration allowance, the effective daily wage came up to Rs 159.

Incidentally, similar to the situation in West Bengal, tea workers in Assam also do not have minimum wage. There also the latest wage was Rs 137. Assam Government also announced interim wages recently, fixing it at Rs 167, around the same time that interim wages were announced in West Bengal. This 14th August, Assam CM is supposed to declare minimum wages, failing which the tea workers of Assam have also decided to strike work, according to sources. The news of the Minimum Wage Committee of Assam having suggested Rs 351 as minimum wage, is the minimum wage that has been prescribed by the committee for all categories of scheduled industries. But neither the Assam Government, nor the plantation owners there seem to have taken it seriously. In fact this can be treated as ignorable.

Incidentally, similar to the situation in West Bengal, tea workers in Assam also do not have minimum wage. There also the latest wage was Rs 137. Assam Government also announced interim wages recently, fixing it at Rs 167, around the same time that interim wages were announced in West Bengal. This 14th August, Assam CM is supposed to declare minimum wages, failing which the tea workers of Assam have also decided to strike work, according to sources. The news of the Minimum Wage Committee of Assam having suggested Rs 351 as minimum wage, is the minimum wage that has been prescribed by the committee for all categories of scheduled industries. But neither the Assam Government, nor the plantation owners there seem to have taken it seriously. In fact this can be treated as ignorable.

Coming back to the West Bengal side of things, counting the probable arrears for a year, if the wage agreement took place in time, and together with the proper ration allowance money that was never paid, the total money looted by the plantation owners from the workers would amount to around Rs 500 crores.

Ironically, even after such a massive loot, the owners are still slithering out when it comes to the question of a minimum wage. The fringe benefits, which are practically non-existent for the most gardens, are being cited to justify suppressed wages. Added to this is the story of losses being incurred in tea trade. Data from the Tea Board has consistently shown not only that there are no losses, but in fact profits from exports and production quantum of tea have only soared. Demand for tea in the domestic market has been rising consistently. The story of loss therefore does not hold any water even under a simple economic scrutiny.

This 17th July, when the Government made it’s first proposal for a minimum wage, this 25% component (covering children’s education, health expenses, festivals and functions, old age savings, etc.) was left out, which clearly amounts to a contempt of the court order. While refusing to accept the offer of Rs 172 as minimum wage, the Joint Forum placed it’s own calculations where the food component alone was shown to amount to Rs. 239.82.

Actually the relationship between the tea planters and the tea workers has been one of fiefdom, over the years. This tradition has continued from the British owners to their Indian counterparts post transfer of power. Now and then, at the cost of blood and lives of struggling workers, certain rights have been obtained, such as the Plantation Labour Act. This historic exploitation of the tea workers in fact received the Government’s official seal of approval right at the beginning, when their wages were being decided for the first time. In any industry, at the time of wage fixation, the worker and family members dependent on her/him are considered. For instance, while fixing minimum wage, the total number of dependents is taken to be 3 people (two adults in the family, plus two children counted as half unit each). In the case of tea plantations, right from the first ever act of fixing wages, this number of dependents was taken to be 1.5. The logic that was presented to back this up was that typically both the adult members in a family work in the tea garden, therefore the wage has to be halved. Thus from the very beginning, wages had been suppressed when it came to the lakhs of workers working in the tea industry – an industry which is highly labour intensive, and is in fact the second largest employment generating industry in the country.

This however could not be any further from the reality. In the tea gardens since long, no more than one adult member from a family is employed permanently. The proportions of temporary workers across the gardens has been rising steadily. The temporary worker is given even lesser amenities than what the law prescribes for the permanent worker. In this situation, the demand for Minimum Wage therefore is in fact the minimum justice that the workers must get, given the burden of this history of “1.5 dependents” that they have been carrying on their shoulders all this while.

According to the law of the land, there already exists a framework for fixing minimum wage. The Minimum Wages Act of 1948, the 15th Indian Labour Conference, and later on, rulings from the Supreme Court stipulate, assuming 3 dependents per worker, 2700 calories of food per person per day, 72 yards of clothing per year, 5% of the total minimum wage for basic housing, 20% for fuel, lighting, etc., and 25% of the total minimum wage for covering children’s education, health expenses, festivals and functions, old age savings, etc. The total minimum wage is to be computed adding together all these components. This 17th July, when the Government made it’s first proposal for a minimum wage, this 25% component was left out, which clearly amounts to a contempt of the court order. While refusing to accept the offer of Rs 172 as minimum wage, the Joint Forum placed it’s own calculations where the food component alone was shown to amount to Rs. 239.82. To this one has to add the costs for clothing, etc. Compromising on any of these amounts on the part of the union leaderships would be tantamount to an incomplete culmination of a promising struggle. The echoes of this refusal to compromise this time, can be heard everywhere across the Hills-Terai-Dooars belt, from loud angry voices at protest meetings-rallies.

The tea gardens of Terai and Dooars are on strike. Although at certain places the ruling party trade unions have opposed and sabotaged the strike, but there is no question about the complete involvement of majority of the tea workers in this ongoing movement. Same is the case in the hills. The ruling party of the hills are singing in unison with the ruling party of the state. The only difference is that the TMC’s trade union is not a member organisation of the Joint Forum, it never was. But the trade union affiliated to the ruling party of the Darjeeling hills have not still left the Joint Forum. Their official stand is that they are not with the Joint Forum when it comes to this specific movement. Other unions operating in the hills are however taking the movement forward, with ever swelling mass support.

Aggressive profiteering practices of plantation owners and their day to day ruthless exploitation of the workers, together with the Government’s complete support to such praxis and complete indifference to the plight of workers – these are the foundational reasons for the crisis faced today by the tea industry and it’s workers. Abandoned gardens and starvation deaths are but only one part of the problem.

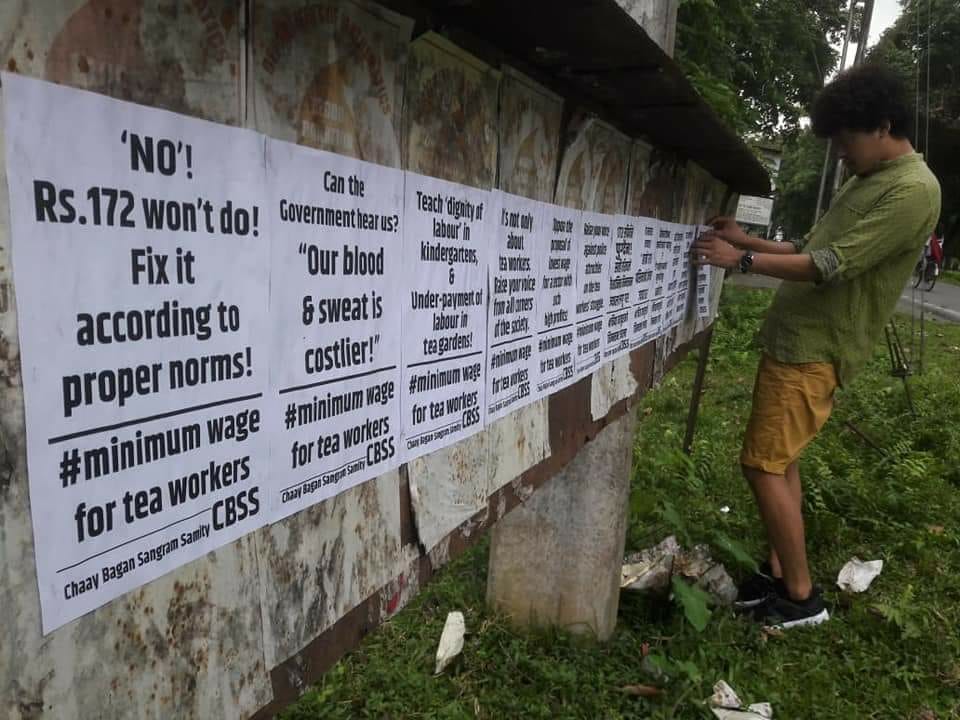

There is no doubt about the fact that this movement has activated the workers, and united them. Organisations such as the Chaay Bagan Sangram Samiti have also joined the movement in solidarity. These are organisations that work not only with the tea workers but also work towards building bridges of solidarity and support between the workers and other sections of the society including intellectuals, professors, lawyers, journalists, poets, writers, students. The issue of the tea workers is also a social issue. Which is why various sections of the local population have come out in active solidarity with the ongoing movement, in different ways.

It is a good sign that this time there is also support emerging from Kolkata and many other places distant from the lives of the tea workers. The enterprise will be worthwhile if this engagement that is getting built leads to realizations on the part of the supporters from outside that the issue of tea gardens in this country go far deeper than only locked-gardens and starvation deaths. One must realize that aggressive profiteering practices of plantation owners and their day to day ruthless exploitation of the workers, together with the Government’s complete support to such praxis and complete indifference to the plight of workers – these are the foundational reasons for the crisis faced today by the tea industry and it’s workers. Abandoned gardens and starvation deaths are but only one part of the problem. Almost all the tea gardens and almost all of their workers suffer everyday from various common shared issues, non-payment, or rather non-existence, of minimum wages being one of them.

We should definitely hope today that this movement for minimum wages brings out all these other crises faced by the tea workers, and expands further the struggle for workers’ rights and dignity.

The author is a political worker, documentary maker and Co-Convener of the Chaay Bagan Sangram Samiti. The photos are courtesy Chaay Bagan Sangram Samiti and other Facebook pages.

[…] „Strike and Despatch Blockade demanding Minimum Wage: Tea workers take to the streets“ am 09. Au… ist eine redaktionelle Streikreportage (vom dritten Streiktag) – vor allem aus der nördlichen Region Westbengalens, an der Grenze zu Nepal („Darjeeling“). Das Gesetz, das seit 1955 eine Sonderregelung für die bengalischen Teeplantagen bedeutet, sieht neben dem Lohn die Bezahlung verschiedener für Arbeit und Leben auf den Plantagen nötiger „Sozialausgaben“ vor, die von Arbeitsschuhen über Essensversorgung auf de Feldern bis zu medizinischer Betreuung reichen. Sozialleistungen, die die Unternehmen in den letzten Jahren willkürlich immer mehr gekürzt haben. Die insgesamt dazu führten, dass der faktische – nicht offizielle, den gibt es bisher nicht – Mindestlohn bei 159 Rupien am Tag liegt, und der Vorschlag der Regierung war es, einen Mindestlohn von 172 Rupien festzulegen, was von den Gewerkschaften rundweg abgelehnt wurde. (Die ebenfalls zur selben Zeit tagende staatliche Kommission im Bundesstaat Assam hatte einen Mindestlohn von rund 330 Rupien vorgeschlagen, was die Unternehmen schlichtweg ignoriert haben, weswegen bei einer Neuaufnahme des Streiks in Westbengalen dieser auch gemeinsam mit einem Streik in Assam stattfínden könnte). Die Regierung Westbengalens, so wird abschließend informiert, habe nun, aufgrund des Drucks der Gewerkschaften, den angekündigten Termin, an dem der Mindestlohn definitiv festgelegt werden solle, vom 20. auf den 13. August vorverlegt. […]