More than a century after the Ghadar Party launched one of the earliest internationalist challenges to British colonial rule in India; its revolutionary legacy continues to live on in Punjab. The annual Gadri Mela in Jalandhar is not merely a commemoration of the past but a living political and cultural space that reconnects history with present-day struggles against imperialism, fascism, and injustice.

By Pritha Paul

Groundxero| December 29, 2025

In the early 20th century, amidst colonization and imperialist war, an internationalist revolutionary movement was brewing, aiming to challenge British rule in India. In the 1900s, a large number of South Asians emigrated to North America and Canada. Among the Indians were mostly people belonging to rural regions of Punjab, many of whom had served in the British military. These immigrants, mostly belonging to humble backgrounds and working in fields and factories, along with some students, formed the Pacific Coast Hindustan Association, which later became the Ghadar Party, with its official founding meeting on 15 July 1913 in Astoria, Oregon. Sohan Singh Bhakna, a labourer in a timber mill, became the President, while Lala Hardayal, a student who arrived from Europe, became the General Secretary.

Unlike the Congress’ ideology of non-violence, the Ghadar Party believed in armed revolution. They also rejected the Congress’ call for dominion status for India and instead demanded complete independence. In order to spread their ideas among the Indian diaspora and to encourage Indians to join their cause, the Ghadar Party established the Yugantar Ashram press in San Francisco in November 1913 with funds raised by the Indian diaspora and Indian students at the University of California, Berkeley. The name of the official weekly publication of the Ghadar Party was Hindustan Ghadar, which especially aimed at inspiring Indian soldiers in the British army to revolt. Its tagline read ‘Angrezi Raj ka Dushman’ (Enemy of the British Rule), and it carried an advertisement for interested revolutionaries: ‘Wanted brave soldiers to stir up rebellion in India. Pay – Death, Reward – Martyrdom, Pension – Liberty, Field of Battle – India.’

Lala Hardayal was the editor of the Urdu Ghadar, and the first Urdu edition was published on 1 November 1913. Kartar Singh Sarabha, a student of the University of California, was the editor of the Punjabi Ghadar, and the Punjabi edition was published on 9 December 1913. In order to protect the members and supporters of the Ghadar Party, names and details of the subscribers were not documented anywhere to avoid them falling into the wrong hands, particularly those of British intelligence. Instead, thousands of these details were memorized by heart. As the Ghadar movement spread among the Indian diaspora in other countries, many revolutionaries began to return to India. With them and other returning immigrants, Hindustan Ghadar reached India, where it was soon deemed seditious and banned by the British government.

During the political persecution of Ghadar activists, the Desh Bhagat Parivar Sahayak Committee was constituted by Baba Vasakha Singh in 1920, himself a Ghadar activist who had recently been released from the Andamans Cellular Prison. The purpose of the Committee was to provide financial, legal and social support to the activists and their families. After independence, the committee became the Desh Bhagat Yadgar Committee, which vowed to keep the unfulfilled dreams and hopes of the revolutionaries alive. On 17 November 1959, the 45th martyrdom day of Ghadar Party member Kartar Singh Sarabha, the foundation stone of the Desh Bhagat Yadgar Hall—a memorial hall paying tribute to the freedom fighters of the Ghadar Party—was laid in Jalandhar, Punjab. Every year since 1992, the Desh Bhagat Yadgar Committee has been organising the ‘Mela Gadri Babian Da’ or ‘Gadri Mela’ to commemorate the Ghadar movement, its members, and its anti-imperialist, secular, democratic ideals, and to keep the flame of revolution burning in the hearts of the people of India.

The Gadri Mela takes place from 30 October to 1 November every year at Desh Bhagat Yadgar Hall, Jalandhar, Punjab. People from all over the country and even from abroad attend the event, and the ambience is one of celebration and festivity. This year was the 34th year of the Gadri Mela, and it was dedicated to the centennial death anniversary of Gadri Gulab Kaur, perhaps the only female Ghadarite. Born in a village called Bakshiwala in Sangrur, Punjab, Gulab Kaur was married off to Mann Singh, and the couple settled in Manila, Philippines, with the hope of one day migrating to and settling in America. But her life changed drastically when she came to know of the Ghadar Movement. Wanting to be a part of the independence struggle, she decided to sail for India and fight on her own land. Her husband, who was initially enthusiastic about participating in the movement, changed his mind at the last minute. Seeing no other option, Gulab Kaur decided to quit her marital life and set sail with her compatriots and comrades.

As the authorities deemed her less of a threat because of her gender, she avoided suspicion while taking part in daring activities, often adopting various guises to evade detection. There is a famous story about the police raiding one of the gatherings of the Ghadarites, who fled in a hurry to avoid arrest. However, they realised they had left behind a trove of arms and critical documents at the raided place. Gulab Kaur, in disguise, returned to the office and recovered the arms and documents in a basket from under the noses of the authorities without being caught or suspected. She also supervised the party printing press in disguise. She would often pretend to be a journalist with a press pass in her hand and distribute arms and ammunition to the Ghadarites. She travelled from place to place, giving fiery speeches and distributing revolutionary literature among the people, inspiring them to join the freedom struggle.

Her fearlessness made her one of the leading members of the Ghadar Party, and she soon became a member of the Central Committee. Any person who wanted to join the Ghadar Party had to speak to Bibi Gulab Kaur, and only when she was satisfied with the person’s intentions would she allow them to join the movement and work with the others. In 1915, Gulab Kaur was arrested on charges of sedition. She was mercilessly abused and tortured for two years for information about the other members of the Ghadar Party and was even threatened with execution, but she refused to reveal anything about her associates. She was eventually released due to lack of evidence, but her health suffered gravely, and she was diagnosed with breast cancer. She died soon after, in 1925.

The entrance of the Desh Bhagat Yadgar Hall was adorned with pictures of Bibi Gulab Kaur, Shaheed Haafiz Abdullah, Rahmat Ali Wazidke, Jiwan Singh Daula Singh Wala, and other female freedom fighters from across the country, such as Begum Hazrat Mahal and Pritilata Waddedar, among others. The premises on which the hall is built is named Shaheed Abdullah Nagar by the Committee, after the martyr Haafiz Abdullah, a leader of the Ghadar Party in the Philippines who was hanged in 1917 in Lahore upon his return to India.

Main Gate of the Desh Bhagat Yadgar Hall or Shaheed Abdullah Nagar

Inside the main building, there is a museum on the ground floor and an auditorium on the first floor. Right opposite the building, book stalls were set up by various publications selling political literature, Punjabi literature, fiction, posters of freedom fighters and eminent social reformers. Across the stalls, a small stage was set up with a big poster showcasing the 25 books banned in Kashmir. Beside the main building was a huge open space with the main stage on one side, where most of the cultural performances took place. This stage is dedicated to Harnam Singh Tundilat, who was one of the founding members of the Ghadar Party and who lost one of his arms in an explosion while manufacturing bombs.

On 30th October, the events started with a painting and photo art exhibition and a discussion on banned books. The exhibition contained paintings of female freedom fighters from across the country; paintings capturing Punjabi culture and the Palestinian struggle; portraits of freedom fighters and of nature; photographs of the Gadri Mela in preceding years, of the floods that plagued Punjab, and of the daily toil of the working classes. There was also a display of an image of undivided Punjab. Just like West Bengal, Punjab, being a border state, is marred by the history of Partition and a tragic nostalgia for its shared culture. The exhibition captured life in Punjab in the 1850s and featured paintings relaying stories of the Ghadar Movement.

During the panel discussion on banned books, speakers emphasized the systemic restrictions placed by the state on issues concerning Kashmir, tribals, and other marginalized communities who are exploited. They stated that forces which challenge the status quo and raise questions against the exploitative system are purposefully silenced—students who came out to support Palestine were harassed and threatened by ABVP goons. The panel warned that soon these restrictions would not be limited to specific issues but would haunt the whole population, the whole nation, and pointed out the changes being brought about in history books, reminding the audience of the book burnings in Nazi Germany. Such actions serve the purpose of altering history, distorting facts in order to hide reality, so it is important to remind ourselves and others of the truth, and to write, publish, and distribute books that speak of the truth.

On 31st October, the day began at 9 a.m. with an opening ceremony. Soon after, a quiz competition began in the auditorium. The topic of this year’s quiz was “Fascism”. The moderator, who also happens to be a trustee of the Desh Bhagat Yadgar Committee, Harvinder Bhandal, explained to the audience that the topic of the quiz was chosen keeping in mind the times we are living in today, the re-emergence of fascist regimes, and the increasing need to resist such regimes. Bhandal candidly admitted that the quiz competition is only an excuse to inform students about history and current times.

Each year, for the quiz, the Committee chooses topics related to history and its lessons. Last year, the topic was “Life of Gulab Kaur”. Prior to that, topics included the Russian Revolution, the Ghadar Movement, the Meerut Conspiracy, Karl Marx, among others. The reading material for the quiz is provided to the students in advance, and in some years the Committee itself has published books on the quiz topics as reading material. Interestingly, the questions were not only based on the candidates’ ability to memorise facts but also tested their understanding and analysis of the material they studied.

Also interesting was the approach of the moderator. Not only did he focus on the correct answers, but he also explained each answer in detail, providing additional information and making the whole process more engaging and informative rather than merely competitive. While discussing fascism in Italy and Germany, Bhandal emphasized how, in a fascist regime, along with the government, the people too turn oppressive. The quiz was not only limited to fascism in bygone eras but also included questions pertaining to present times as well.

One of the quiz rounds focused on the Palestinian struggle, with questions regarding the inception of Zionist ideology, the formation of the state of Israel, and the history of the struggle for Palestinian liberation, such as the formation of the Palestine Liberation Organisation—questions that have largely been pushed to the background by imperialist forces. Questions were also dedicated to the Rwandan genocide, the violence against the Rohingyas, and contemporary India.

Around seventeen schools and colleges from all over Punjab participated in the quiz, with each team comprising three members. When asked about youth participation, Bhandal responded, saying, “There was a time when around 40 schools and colleges would participate. But times have changed now. The environment greatly affects people, and we do not see as much participation as before, though many students are still participating. One key reason behind the decrease in participation is that the state has begun to organise a youth festival exactly overlapping the dates of the Gadri Mela. It is being purposely organised in parallel so that participation here is affected. We have submitted representations to the government, made several requests, and tried to explain the cultural significance of the Gadri Mela, but to no avail.”

While it might seem absurd that the state would take such effort to curb attendance at an event commemorating the freedom struggle, anyone attending the event can understand why. The Gadri Mela does not merely glorify the days gone by; it raises pertinent questions with respect to the present and aims to imbibe in the youth the same revolutionary fervour that motivated their ancestors to challenge the status quo for a better future devoid of division and exploitation. Evocation of empathy among the people has always been a threat to state machinery.

Apart from the quiz competition, there were also singing, painting, and speech competitions. Youngsters participating in the singing competition sang fiery songs of resistance and hope, imagining the establishment of Begumpura—a place without caste, division, or sorrow. Around 29 other youngsters participated in the speech competition and delivered inspiring and insightful speeches on pressing issues, bringing questions of caste to the forefront. One youth focused her speech on the use of social media by ruling forces in society against the interests of the vast majority of the working masses.

Such engagements truly reveal the deep impact of the event on young minds, who are encouraged to think consciously and critically about the system they have inherited. On the other hand, children and young adults of various ages made paintings of Ghadarites and paintings on Palestine, calling for peace and an end to wars.

Thereafter, a conference was held in the auditorium where guest speaker, economist and political commentator Prabhat Patnaik, spoke about the dangers of neoliberalism and imperialism. “Neoliberalism is the main face of capitalism in recent times. The problem with neoliberalism is that capital and commodities can move easily across borders, which means workers have less bargaining power and fewer rights. Fascism rises when there is a crisis in capitalism. Capitalism is in a terminal crisis. Rosa Luxemburg stated that there will come a terminal crisis in capitalism. There was a Gujarat Global Investors Summit in 2013, and it was decided that Modi would lead the alliance between monopoly capital and fascist forces. Increases in tariffs and increased militarisation also have roots in neoliberalism.”

Patnaik went on to emphasize the dire conditions in which the majority of people are living and how resources are concentrated among a few. “I have calculated that if we want to give people five fundamental economic rights—and we do not have fundamental economic rights in the Constitution—such as the right to food, employment, free public healthcare, education, living non-contributory pensions, and disability pensions, the resources can be raised in two ways. Either the top 1% should pay a 2% income tax, or a one-third inheritance tax should be imposed on the top 1%.”

The next guest speaker, Punjabi playwright, poet, administrator, and editor Swarajbir Singh, began his speech by invoking Avtar Singh Pash, a revolutionary Punjabi poet whose words, he said, are all the more relevant today. Singh recited a poem by Pash titled Sade Samian Vich (‘In Our Times’), which expresses resilience in the face of adversity. Singh spoke about the birth of fascism in India from the womb of colonialism with the help of Hindutva forces like Savarkar.

He distinguished Indian fascism as rising slowly and through different fascist organisations, as opposed to fascism in European countries, which developed quickly and was more individual-centric, centred on figures such as Hitler or Mussolini. Invoking the example of the farmers’ protest, Singh explained that the only way to counter fascism in India is to truly achieve unity among the people—of revolutionary organisations, trade unions, political organisations, and civil society—and to continually maintain this unity. He emphasized that such unity will not be possible until the working masses demand it and create pressure on these organisations to work in their favour.

The next events were a poetry competition where the candidates recited feminist and anti-colonial poems and book launches, after which two films were screened. The first short film, The Present, is directed by Farah Nabulsi. It follows a Palestinian father and daughter trying to navigate the Israeli check points in occupied Palestine and their struggle to bring a present across the check points for the wife and mother, waiting for her family back at home. The next film to be screened was a documentary called Loha Garam Hai directed by Biju Toppo and Meghnath. The documentary traces the lives of the people affected by the fastest polluting industry of sponge iron and their struggle to save themselves from the hazardous effects of land, water and air pollution caused by the coal-based plants producing sponge iron while they also resist forceful acquisition of land in their villages to build these very plants which threaten their life and livelihood.

A scene from Jhande Da Geet depicting Gadri Gulab Kaur joining the Ghadar Movement in India

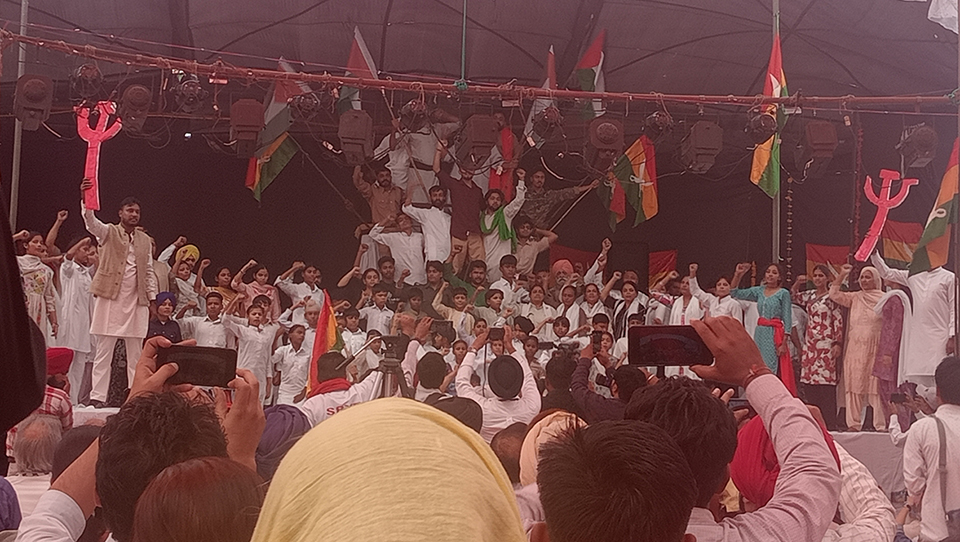

On 1st November, the main event of attraction was the Jhande Da Geet or the Flag Ceremony which started at around 10:15 am on the main stage – Harnam Singh Tundilat Manch. The stage was adorned with numerous flags of the Ghadar Party as well as photographs of Gadri Gulab Kaur, revolutionary theatre artist and activist Gursharan Singh and student activist Umar Khalid who has been in jail without trial for more than five years. These three images perfectly represent the anti-capitalist, anti-imperialist, secular ideology of the Ghadar movement. While Bibi Gulab Kaur represents women’s contribution in the making of this country, Gursharan Singh who opened the world of theatre to the toiling masses of Punjab becomes a symbol for the Gadri Mela itself which attempts to awaken the conscious resistance of the people against power structures and religious dogmas through culture and conversations. Umar Khalid’s picture remained as a representation and reminder of all the political prisoners who have been and are being persecuted by the state because of their courage and conviction to raise the demands of the most marginalised, most oppressed, most exploited classes of the society. All the political prisoners – from the activists incarcerated in the Bhima Koregaon case to the Muslim students arrested for their anti-CAA protests, from G.N. Saibaba and Prashant Rahi to Siddique Kappan, Aasif Sultan and Khurram Parvez – would come to be invoked again and again in the various performances and speeches in the Gadri Mela to the extent that they became an integral part of the event through their very palpable absence, much like the Ghadarites.

A Scene from Jhande Da Geet or the Flag Ceremony Performed on the Main Stage or Harnam Singh Tundilat Manch

Before the Flag Ceremony began, Kalvinder Singh, a member of the Indian Workers’ Association, UK – an organisation attempting to unify the working classes in the United Kingdom – spoke about the life and works of Bibi Gulab Kaur, about how she would sarcastically implore men to sit at home afraid while the women freed India from the British, about how she became an integral part of the Ghadar Party, about how she would make the flags of the Party and about how she endured all torture and abuse by the police without breaking or bending before the authorities. The Flag ceremony comprised of children and youngsters coming together to perform a musical play enacting the life of Gadri Gulab Kaur, her marriage and travel to Philippines, her introduction and engagement with the Ghadar Party, her conscious decision to leave her husband and family life behind to travel back to India to become a freedom fighter and her daring feats as a leader of the Ghadar Party – fighting the British forces with her courage and wit, imbibing the Ghadar ideology in others and inspiring them to join the cause. After the Flag Ceremony, a book was launched titled ‘Kirti Leher di Veerangana – Bibi Raghbir Kaur’ which is an extremely significant book, given that it is the first book to be published on the life of Bibi Raghbir Kaur who was a member of the Kirti Kisan Party and a member of the first Punjab legislative assembly, and who was also instrumental in inspiring women to join the Kirti Kisan Lehar – the peasant-worker-landless labour resistance movement which swept Punjab in 1928 inspired by the Ghadar movement and its militant nationalist and anti-imperialist ideologies.

Next was welcomed on the stage, Mohamad Yousuf Tarigami, a member of the Communist Party of India (Marxist) and a member of the Jammu and Kashmir legislative assembly. Bhandal, who introduced Tarigami to the audience, also emphasized on the need to inform ourselves of the conditions in Kashmir and the plight of the Kashmiri people. Tarigami began his speech by invoking the history of revolutionary struggles in India and in Kashmir and by reminding the audience that when Kashmir was under Dogra rule, the people of Punjab had raised their voices for the independence of Kashmir. He explained to the audience the dire state of Kashmiri people and categorically stated that the silence in Kashmir does not accurately reflect the feelings of the Kashmiri people and that the silence should not be mistaken as acceptance or resignation to fate, but instead their resilience which will help them rise up again. Drawing parallels with Palestine, he expressed how around the world, empires are scrambling to survive and as a result exerting greater pressures on the working classes around the world. But, drawing parallels with the Gadri movement and the independence struggles against the British Empire, he expressed hope that all empires crumble eventually and the will of the people stands as the last will.

The next speaker was Dr. Navsharan Singh, a feminist author and human rights activist. She began her speech by commemorating the contributions of women like Gadri Gulab Kaur, Raghbir Kaur, Durgawati Devi, Bibi Amar Kaur, Kalpana Dutt and Pritilata Waddedar who have historically had a significant role in resistances against colonialism and imperialism but who have largely been invisibilised. She also paid tribute to the farmer-peasant rebellions in which women played a huge role and which paved a new path for the people of India, such as the Tebhaga Andolan, the Telengana Andolan, the Naxalbari Andolan and the more recent Farmers’ Protest, and she emphasized the direct relation between imperialism and famines and starvation and the direct impact it has on women who have to raise their families in such dire inhuman conditions. She brought up the plight of Dalit women who are still fighting for their rights. Most importantly, she lamented that though we have gained independence from the British, we have failed to create a country which was truly envisioned by the revolutionaries like Gulab Kaur and Bhagat Singh – a country of all equals. She continued to commemorate the different struggles of women, be it the women of Kashmir or the women of Manipur who dared to expose the injustices of the Indian armed forces, be it cultural activists like Jyoti Jagtap arrested in the Bhima Koregaon case, be it the students and activists who have been wrongfully incarcerated by the Indian state among whom Gulfisha Fathima is one, a member of Pinjra Tod – a feminist organisation which protested against curfews on women in hostels and institutions and demanded women’s share of the night and the sky. She criticised the state for its suppression of free speech and wrongful incarceration of Muslim activists in order to win over their vote bank and she also lamented the inaction of the courts to bring the political prisoners to justice and prolonging their incarceration without any trial. She ended her speech by comparing the incarceration of the Ghadarites to the incarceration of today’s political prisoners, who the state wants us to forget, but the Gadri Mela is a testament to our remembrance, it is a testament to our collective resistance, and it is a testament to women’s indispensable role and leadership in the revolutionary struggle.

The fiery speeches of the guest speakers were followed by various other performances, with artists presenting revolutionary songs and plays on various topics of social relevance. There were plays on the Ghadar Movement and the life of Gulab Kaur. There were satirical plays focussing on issues like unemployment, the corruption in our judicial system and the genocide in Palestine. There were tragic dramas relaying stories of partition – an event that looms over Punjab as much like a dark cloud as it looms over West Bengal. Despite his age and ill health, Baba Nazmi, a labourer, trade unionist and revolutionary Punjabi poet from Pakistan graced the event with his presence on call and expressed his desire to attend the Gadri Mela when his health is better. He parted with the gathering after reciting two lines which resonated across state borders, even obliterated them, and lingered for all to ponder upon:

“Majdoora Da Jad Vi Murka Dolega

(Whenever the working class shall rise in rebellion)

Himmatwala Hor Ek Bua Kholega

(The courageous will open a new door).”

The cultural performances went on throughout the night and continued till the dawn of 2nd November. The stage was abuzz and with the thousands of audience members watching intently, it did not seem like the state’s Youth Festival could affect the turnout at the Gadri Mela much. The Mela, after all, is unrivalled for those with a fervent revolutionary spirit and no amount of desensitised glitz and glitter and bollywood-type glamour can outshine the fire that the Mela seeks to ignite in the hearts of their people.

Most of the Ghadarites belonged to humble backgrounds – most of them being workers and labourers – and most of them did not receive much education, but they dared to dream of a future where there would be no class divisions, no rich or poor, no exploitation or oppression of one over another, no kale angrej or Indian ruling class, and no religious dogma. The secular ideology of the Ghadar Party is perfectly encapsulated in the act of the Ghadarite Udham Singh who adopted the name ‘Ram Mohammad Singh Azad’ to represent the three major religious groups in India. The word Azad represented his free spirit and his anti-colonial, anti-imperial stance. This is the name he was hanged with after he stood in a British court before a British judge facing a British jury and condemned British imperialism. As a people, despite inheriting the history of our ancestors, we have failed to realise their dreams. We have failed to build the nation that they envisaged. The Gadri Mela reminds us of this harsh truth but also encourages us to work towards these dreams.

But its significance is not limited to just that. In a country where all the freedoms and festivities are reserved for the powerful and the power-hungry, in a country where the press is silenced, students and activists are wrongfully incarcerated under false grounds as a warning to others against raising difficult questions, in a country which occupies a people – the people of Kashmir – takes away their statehood and leaves them invisibilised and throttled, the Gadri Mela serves as a respite to the people who want to feel, who want to speak, who want to sing, who want to resist – this is the people’s festival. In a country which wants to rewrite history by renaming places with Urdu names and branding Muslims as terrorists, the Gadri Mela is held on premises named after a Muslim martyr. In a nation steeped in hatred, ignorance and religious dogmas, the Gadri Mela provides a space to celebrate the love of people and their shared dreams of a fulfilling future, and it provides the tools with which to build this collective future – history and hope.

Pritha Paul is a legal activist and member of Groundxero Collective.

Feature Image: Prabhat Patnaik, speaking about the dangers of neoliberalism and imperialism at a conference organised during the Gadri Mela.