Amma’s Pride and If (in Bengali ‘Jodi’) – a documentary and a short film respectively, were screened at Dialogues: Calcutta International Film & Video Festival 2024 on 30th November and 1st December at the iconic single screen cinema hall ‘Basusree’ in Kolkata.

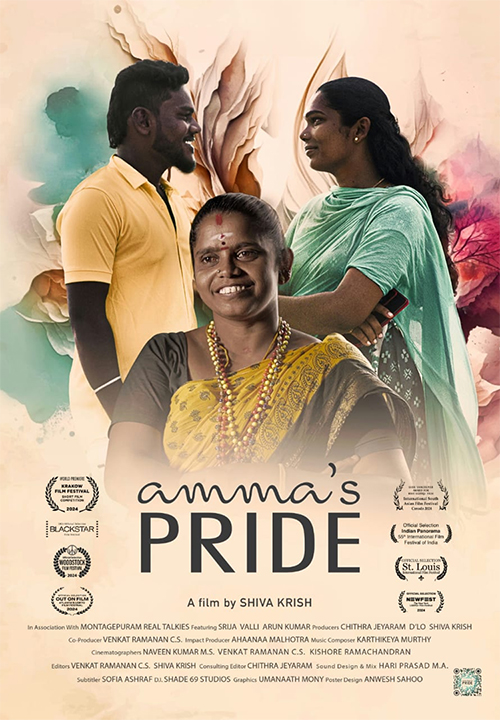

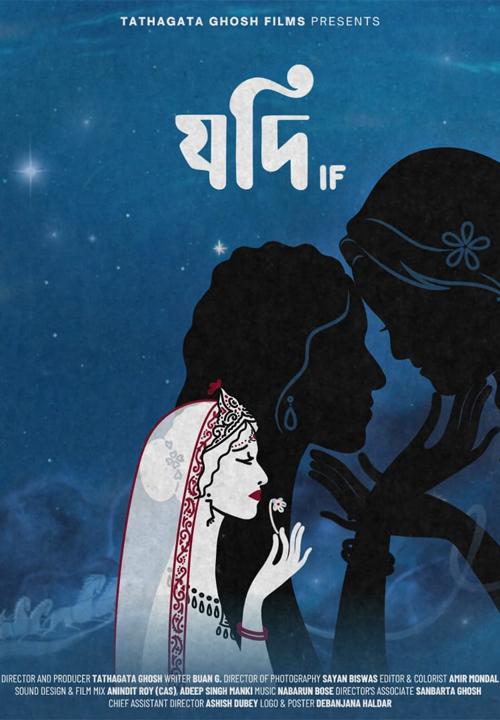

The themes of both these films are ‘marriage’. Though different in forms, both the directors Shiva Krish (Amma’s Pride) and Tathagata Ghosh (If) have taken a nuanced look at the idea of marriage within the trans & queer community. Also, in both the films, the mothers of the protagonists play an important role.

Amma’s Pride tells the real life story of Srija, a trans woman from South India, and how Srija navigates the complexities of marriage, advocating for its legal recognition while also battling to sustain it, all with the wholehearted support of her mother Valli.

Tathagata Ghosh’s If tells the story of Jaya and Fatima, two women deeply in love with one another and desire to have a family. They dream of a future together that would seem straight out of a fairytale. But then destiny has planned for them otherwise.

Sudarshana Chakraborty from Groundxero spoke to directors Shiva Krish and Tathagata Ghosh about the idea of marriage, marriage equality, relationships, power dynamics in relations and the socio-political backdrop that both the directors brought subtly in their films.

Sudarshana Chakraborty (SC): Other than Srija’s case making headlines, was there any other reason that you chose it as the theme of your first documentary?

Shiva Krish (SK): Honestly the case was the reason. The legal victory of Srija was very important, it happened in 2019, and I felt it’s very very important to tell the story to the world through a documentary film, and that’s how it started for me actually. That’s how I initially started. That’s how I approached the film, by getting along with Srija and her family, getting to know them more, and all the things. But only after I got closer, I realized the value of her mother Valli, who has been her biggest strength working from behind. So that was something none of the media had reported at that point of time in articles about Srija’s legal victory. So that was something I didn’t know. I thought that’s where the film should focus and I directed the film towards that angle. That’s the journey so far.

SC: In the process of making the film, which character became more important to you – Srija Valli, Arun (Srija’s husband) or the concept of marriage?

SK: All, I mean all of them were important. As I told you, I started out with Srija. See, for Srija herself, her mom and her husband, both are equally important. So we also channeled the film towards all these angles, to make all these characters as integral to the film as it is for Srija herself. So that was the core of the film and that’s how it came out.

SC: As a young filmmaker or a young person in today’s India how do you view marriage as an institution or a concept?

SK: It should be left out to an individual person, basically one should decide their own marriage, that should be ideal, someone else should not decide for an adult. So, whether to marry, who to marry, how to marry, whether not to marry, it should be decided by the person, an individual, by the couple themselves, rather than by someone else from their family members deciding it. Unfortunately our culture in India has been such that the family decides marriage, it shouldn’t be that way. I hope this changes in the future.

SC: To the sexually marginalized community ‘marriage’ is often seen as a right which is denied to them. So while making this film how did you deal with that?

SK: Basically as you said, the idea of marriage is very important here in the film’s context. Because see, the whole point as I started the film was LGBTQIA+ marriages. Srija’s legal victory was a huge stepping stone, for her and as well as for the community members. Her case has been studied in various law schools. It’s very iconic. That’s how the film starts. But it’s just not about marriage or legal victory. What happens post marriage? What happens before that? There is a huge journey, pre and post the victory. To a common man, only the victory is visible, every time, not only in her case, only the victory is visible, but what are the things they have paid for that, is what our film covers in depth. That’s important for everyone to know because otherwise it’s difficult for a common man to understand what goes behind this, what cost they pay to make this happen. For example, Srija had to sell her gold ornaments to continue the legal process because they were from a working class background. And also it was very vital that they filed the public interest litigation (PIL). They could have easily filed their own case but they still chose to file a PIL for the larger community. That is something which is very important. If Srija can do it, I’m sure anybody else can do it.

SC: How do you see the political angles of marriage? In the film Srija’s mother mentioned the happiness on the day of Srija’s marriage as like ‘winning an election’. On the other hand Arun’s mother didn’t approve of the marriage and said if Srija would have belonged to Dalit community, even then she could have accepted Srija but not Srija being an transgender. You kept both views while editing the film. Tell us what you think of such thoughts?

SK: There is a reason of course. Both the mothers’ views are important and they find place in the film. Even though their point-of-views are different, opinions do differ – their views come from the fact that they both love their children so much.

SC: Other than loving their children, as a director, how do you decipher Srija’s mother Valli’s comment when she says it was like ‘winning an election’?

SK: It sums up the whole community’s aspect of legal victory. Even after section 377 and a lot of legal victories before, it was like winning an election. This was also one such moment. So every time the community has to come up and break that barrier it is like ‘winning an election’. So Srija’s mom Valli has summed it up and articulated it beautifully. It’s the best that she could have articulated and of course it stayed in our film.

SC: And probably it also shows the stereotype about transgender community when Arun’s mother says she could have accepted even if Srija belonged to a Dalit community.

SK: That’s the politics as you said. Not just the marriage, the whole LGBTQIA+ community as well, because that’s how they are seen from the perception of a common man, that’s how they are seen as the lowest of the low. And it sums up how they are seen in general perception.

SC: When you spoke to Valli while making the film, what do you think made her support Srija’s marriage and the struggle?

SK: Valli is like any other general parent in India where all the parents believe my child will be happy after marriage and my child should have a happy married life. That’s the perception of any parent and that’s how Srija’s mom’s aspirations were too.

SC: When you communicated with the community people, Srija’s neighbors, what was their reaction?

SK: I’ve been part of a lot of NGOs during the Chennai flood. I’ve worked with queer community people and have been volunteering. They were all quite aware of Srija’s case. When I started filming it was post working in the community. Everyone was definitely positive towards Srija’s legal victory and wanted it to be highlighted.

SC: When Arun left Srija for a time being and Srija was hiding it from others – do you see that insecurity similar with or different from hetero-normative couples?

SK: The insecurity was very similar, similar to hetero-normative couples as well. We society is conservative. Thutukudi is a small town, even in big cities couples do not tell the neighbours that they are separated. So it’s very common in our Indian families.

SC: Have you shown the film to the community people?

SK: Yeah of course. Even while making the film, even during the rough-cut stage, we have been showing the film to lot of community members, from time to time, to get their views, and know how politically right the film is, from the rough cut stage to the final cut, it was shown to many community activists and their responses were amazing. They were very happy. They kept on asking – “When will you finish?” “When will it come out?” One of our producers is a transman, a Srilankan-American, he is also from the community. When he saw it during the rough cut, he was very very happy about it and said that he wanted this message to be out in the world as widely as possible and indeed that’s why he became a part of our film!

SC: While you were making the film the ‘marriage equality’ case was going on. What do you want to say about that?

SK: It was very disheartening, that they did not legalize it. We are planning to do a social impact campaign through our film. We are planning a five-city tour in India and five-city tour in the US, as well as we are planning to cover rural Tamilnadu. There are more than 12600 village panchayats in Tamilnadu where we are planning screening along with discussion post-screening. We really hope this film to be a call to action more than a film as such because it’s very important to create awareness, once this awareness is there the next things will definitely be happening. We hope our film will enable that. That is one of the primary reasons for the positive portrayal of Srija’s mom Valli as well as highlighting the legal victory of Srija’s marriage – both are very important parts of the film and we want it out in the world.

Sudarshana Chakraborty with Tathagata Ghosh

Sudarshana Chakraborty (SC) How do you view marriage as an institution?

Tathagata Ghosh (TG): I think marriage as an institution is sometimes confused or misunderstood, because I feel that first of all it’s an individual’s choice. And it should not be forced or imposed, as we have also explored in our film ‘If’ (‘Jodi’ in Bengali). Sometimes you impose a decision on someone and that does not lead to good consequences, because we often overlook the personal choices of the partners. What we often hear in India is that marriage is between families. I don’t agree with it personally because marriage is between two individuals. It’s about living together, it’s about trying to find the best out in both the people amongst one another and respecting each other’s choices. But as we often see, that’s not the case. That’s why I feel it’s confused, it’s misunderstood. It should be left on individuals and their choices. That’s what I feel about marriage.

SC: Any particular reason that you chose this theme?

TG: Actually there are few reasons to choose. First of all, the events in this film are based on certain true incidents that I have seen. I wanted to explore the middle class life, milieu, the spaces where I’ve grown up, the cramped spaces, so those are the spaces I wanted to explore through visuals, through cinema. And other than that I also wanted to explore the displacement of minorities. Religious discrimination – as we see through the character of Fatema, that is the one aspect I explored, though not very directly, but that is also a plot point in the film. So what’s happening around us, socially, politically, all of it combined – I wanted to make this film. So there are three, four reasons for me to make this film – exploring those spaces, exploring middle class Bengali life, and of course true stories, and even though it has been a few years that homosexuality has been decriminalized in India but still I feel the acceptance of it, that is still a far fetched dream. Individual choices are not respected. These complexities, I wanted to explore, and that is the reason I chose to make this film.

SC: As you said you wanted to explore middle class social space and your films usually distinctly portray this kind of social realities. What was there in your mind while you were exploring the middle class social realities through your characters in the backdrop of same sex relationship, marriage, parents, neighborhood?

TG: I think all of it was in a way I would say very autobiographical because these are things, these are people I have actually seen up close. I would say I didn’t have to do much research per say on these characters because I’ve grown up with these people. Growing up in a very conservative, patriarchal society, I was surrounded by these kinds of people. So, for me…as we see the acceptance by the mother (of her daughter being homosexual), in real life I have not seen this thing unfolding. I think cinema is a medium where what I see wrong around me I can set right. That is like living in a fantasy, but that is what cinema is for me personally, and that is where I think personal catharsis is all about. So that is how I chose to explore these characters. That’s the route I took basically.

SC: There were subtle moments, dialogues where you made strong socio-political statements, for example in the context of a minority woman’s identity. What was going in your mind while you were writing the script, the dialogues?

TG: For me at the end of the day ‘If’ ( ‘Jodi’ in Bengali) is a very human story, it’s a story of relationships, but the social discourse I wanted to have, that had to be sub-textual. So I didn’t want it to be on the face. The previous short film I made, ‘The Scapegoat’ (‘Dhulo’ in Bengali), there, things were shown very directly, on the face. That is something I would not do anymore in my films, because over the years, I’ve realized there are personal things to say. I think there is a fine line between filmmaking and activism. I don’t want my films to be rants of an activist. Because films should be visual and there I’ll say what I’ve to say about what is going around me but in a very sub-textual way, so that they do not feel on the face. People should see a human story unfold and then what I am trying to say politically will also come across, if it’s a story well told. So that’s how I went about exploring the narrative this time, as far as socio-political discourse is concerned.

SC: Why did the mother of one of the protagonist women become important to you?

TG: For me it comes from a very personal space again because I lost my father when I was 21. Honestly, I would say my friends or me sometimes didn’t see the unfiltered love that we should have from near and dear ones. And I think about the role of a mother… over the years I’ve realized how important it is. Not for any individual personal choices, but just as a person. Certain choices we make in our career also, it is very important to have support of your parents, be it a mother or a father, and as we have both of their selves inside us especially our mothers because they carry us in their wombs for nine months. So I think the mother figure is so important to me, and the love probably sometimes which we took for granted when mothers are concerned. Through the films I do I try to underline the fact that – Mothers are important and their love and support mean the world to us.

SC: In your movie the character of the mother becomes a strong, independent woman character also within her limited scope or space in a conservative, patriarchal family, she was taking a stand. You developed the character like that.

TG: Absolutely. That’s what I just said. In our real life I’ve seen exactly the opposite in the mother figure. So in the film I tried to flip that and kind of maybe fix that. Fix the wrong doings, sometimes the mothers are bound to…because they have almost surrendered to the patriarchal norms. Probably I wanted to correct it in a way. That’s why the character you saw.

SC: There is discrimination regarding marriage in our society. From our stereotypical social understanding we often describe it as an institution, we talk about choices. But to the marginalized community it is often seen as a right which is denied to them. Would you like to comment on that?

TG: I think discrimination is there and last year when they filed a petition also (the marriage equality petition), the outcome was not what we desired it to be. But I think this is high time, because marriage as I said is a very personal choice and still the patriarchal system of controlling lives exist pretty much. For me, it’s just a human being, it doesn’t matter about gender, sexuality, caste, religion, class – whatever it is, it is about choices and we should respect those, that’s what I feel and I hope that the justice system of our country will understand this and will make amends to the existing set of norms or laws.

SC: One of the interesting parts of your film is the male character (the husband) whom you didn’t portray as a negative one. We have often seen that there is always a chance to do so. How and why did you avoid the trope?

TG: I think I was very clear that there will be no negative character in this film. No one is bad. For me all the characters in this film are victims of circumstances. I wanted the husband to be a real Bengali ‘bhadralok’. The husband, the mother, the lovers, all of them are victims, all of them want choice, that’s why the name of the film is ‘If’. If I had made that choice, things wouldn’t be this way. So this is about the one choice we make and that is exactly the choice of marriage also that we are talking about. So it was that one choice which has created an upheaval knowingly or unknowingly in their lives. I wanted the male character, not a good or a bad guy but grey and somewhere between a good person, a typical good man, who is not scary. In some screenings I heard that the audience thought the husband will turn out to be a villain, which was not my intention at all.

SC: If it was a relationship between two gay men, and you had to portray the character of a ‘wife’ would you have shown her like this also?

TG: Absolutely. Probably. I’ve not given it a thought but I think I would definitely make them…I would have made them grey.