The adoption of the new National Education Policy (NEP) on July 29 by the Council of Ministers in the BJP-led central government has received an enthusiastic reception from a wide section of popular personalities. That such a policy renewal came 34 years after the last such exercise (NEP 1986) has created hope that the problems we face from a highly unequal educational hierarchy, increasingly disconnected from the life and labour that sustains crores of Indians, will now be looked into. Even those who are often critical of the ruling regime, have applauded the vision behind this document, while at most reserving judgment on the nitty-gritties of its execution.

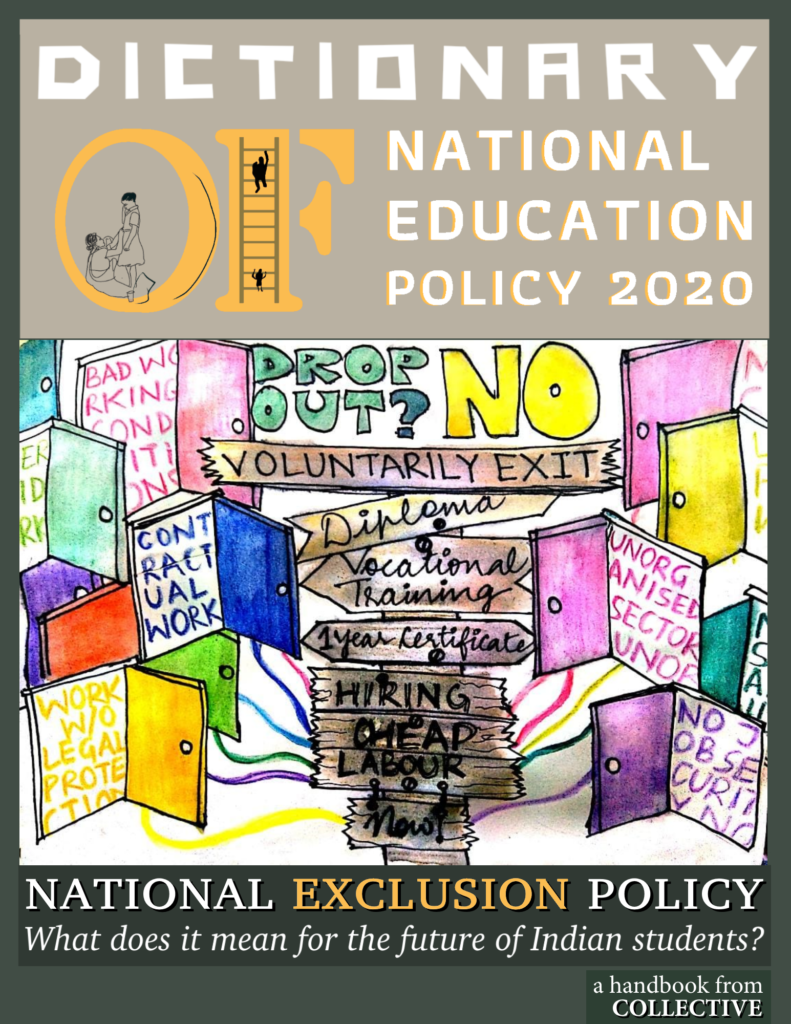

A recent booklet titled ‘A Dictionary of National Education Policy 2020’ published by COLLECTIVE, a left revolutionary student organization based in New Delhi, argues that ‘A closer look at the document as well as the track record of successive Indian governments in education, reveals that some of the very ideas that are causing much enthusiasm today, in fact, have very different meanings.’ Below is an excerpt from the report.

The revised draft of NEP 2020, adopted by the Cabinet without democratic deliberation in either house of the Parliament, has seen enthusiastic support from a sizable section of personalities who are often known to be critical of the present ruling dispensation. From electoral opponents such as Shashi Tharoor, Yogendra Yadav and Chandrababu Naidu to popular opinion-makers such as journalist Rajdeep Sardesai, academic Pratap Bhanu Mehta and virtual celebrities Dhruv Rathee and ‘Deshbhakt’ Akash Banerjee, many have supported the broad thrust of this change in the education system while holding marginal reservations.

This raises important questions, not just on this policy document, but on how any policy document should be read and responded to. Should not a policy document be read in the context of who is bringing it, what are their stated agendas and how such words have turned out in actuality in the past? The present NEP 2020, even in good faith, assuming that the government will indeed stick to its words, retains several fundamental flaws.

For instance, the government might come up with a vision document claiming that today’s environmental laws are ‘outdated’ and in need of ‘reform’, so as to make them ‘flexible’, ‘time-bound’ and ‘friendly’ to ‘all sections of society’. It might claim that now, we must utilize our resources to equip the nation to ‘compete in the global arena’. Given consecutive governments’ history of ecological devastation, one might conclude that ‘flexibility’ and ‘friendliness’ for ‘all sections’ would mean big multinationals being given a freer hand to circumvent the norms of clearance, compliance and impact assessment, in the name of ‘development projects’, to the ultimate detriment of the environment. Is it not clear that the forests, mountains and rivers, which they may claim are ‘lying idle’, will now be sold off to big business houses in the name of ‘utilizing resources’ and bringing ‘development’?

Or, say for instance, if similar sentences are written for labour law ‘reforms’, is our experience with such changes over the last three decades not enough to clarify that the government intends to further ramp up contractualization of labour, loosen safety requirements for industry, make employers free from their social security obligations and so on. Should we then choose to appreciate the intent of such environmental or labour policies and later criticize its actualization?

One need not even be a ‘crazy Communist’, have a ‘negative outlook’ or be part of an ‘anti-national conspiracy’ to understand this. The question here is not just about the ‘intentions’ of the ruling establishment and their history of putting up nice but deceptive, empty words to disguise their aims. Whenever a policy document is to be critically appreciated, it needs to be seen in its context, seen for what possible shape it will take when it is realized in a society riven by large structural inequalities along different axes.

One method is to see what shape it takes for the ‘under privileged’ and whether the policy uplifts them in absolute and relative terms with respect to the privileged. In other words, the impact of the policy must be evaluated in terms of whether it will decrease existing inequality or increase it. But such a method of looking at policy becomes an agenda only if we are convinced that ‘inequality’ is bad, not just for the under privileged but for the progress of our entire society and country. We would argue that there has been a shift in the discourse in this aspect and hence many are complacent in reducing this aspect of structural inequality to mere ‘implementation issues’ of an otherwise progressive policy.

Indeed, a ‘bold change’ in our present education system has been an urgent requirement. It is has been long-awaited by the toiling and oppressed sections of Indian society and by progressive students, teachers, educationists and citizens. The changes to be brought by NEP 2020, however, are the opposite of what has been expected. In this booklet, so far, we have presented an analysis of the different aspects of the policy, decoding the words in the document itself. Here, in this afterword, we will focus on two unsaid but fundamental assumptions that are driving NEP’s policy makers and their enthusiastic supporters.

The first assumption behind this push for early vocational education is the following. It is assumed that the lack of adequate/appropriate skill within India’s labour force is the primary cause of India not becoming able to attract investment from domestic and foreign Big Capital and for the lack of ‘economic growth’. Through vocational training from late childhood and an extensive skill development program, India will be able to harness its ‘demographic dividend’ (that is, the fact that we currently have a young population) and will become a hub of cheap, skilled labour. This will lead to foreign/domestic capital investment, therefore, ‘economic growth’ and ‘development’ in the country.

But the reason for foreign direct investment (in productive sectors) in India remaining low is not due to the lack of skilled labour. The domestic market too is not suffering from any lack of labour supply given the huge labor-surplus in our economy but from a lack of aggregate demand. So, the question remains: even if we do enhance ‘marketable skills’ among young people, who is going to buy those skills? Or, simply, where will these skilled workers (now burdened under student loans) get employed? Thousands of those who are already skilled in these sectors are getting retrenched or not finding dignified employment. In economic terms, the policy is aimed at ‘supply side’ management, which will not mitigate an economic problem which lies mostly on the ‘demand side’.

There is an added layer to the problem in the first assumption. In this framework of development through investment of domestic/international big capital, the terms of winning the ‘investors’ confidence’ in ‘developing countries’ like ours is its ability to offer the cheapest labour and give away its natural resources at throwaway prices. The point is, even if India is able to win this game of pleasing investors over other backward nations, the future of our country and its young population will remain doomed.

Proponents of NEP 2020 are relying on an ahistorical understanding of economics. They hide the fact that countries with a history of colonial exploitation like ours have been able to grow economically only if they have made rapid advances in primary and secondary education for the whole populace, made a robust indigenous base of higher education, including research, and thereby secured a foothold in the scientific and technological fields. Only then have they been able to integrate themselves in the global economy on their own terms. The upper ten percent of society, in any underdeveloped country like ours, aspires to integrate themselves more closely with the global elite because they are, to an extent, a direct beneficiary of this economic model. Among the remaining ninety percent, for whom an opportunity for upward mobility has opened only formally, some are ardently supporting such an economic and educational model. But it is historically proven that for the overwhelming majority, these dreams of upward mobility will never get actualized in the existing neoliberal model. Rather a substantial section will get further pauperized and entrapped in debt.

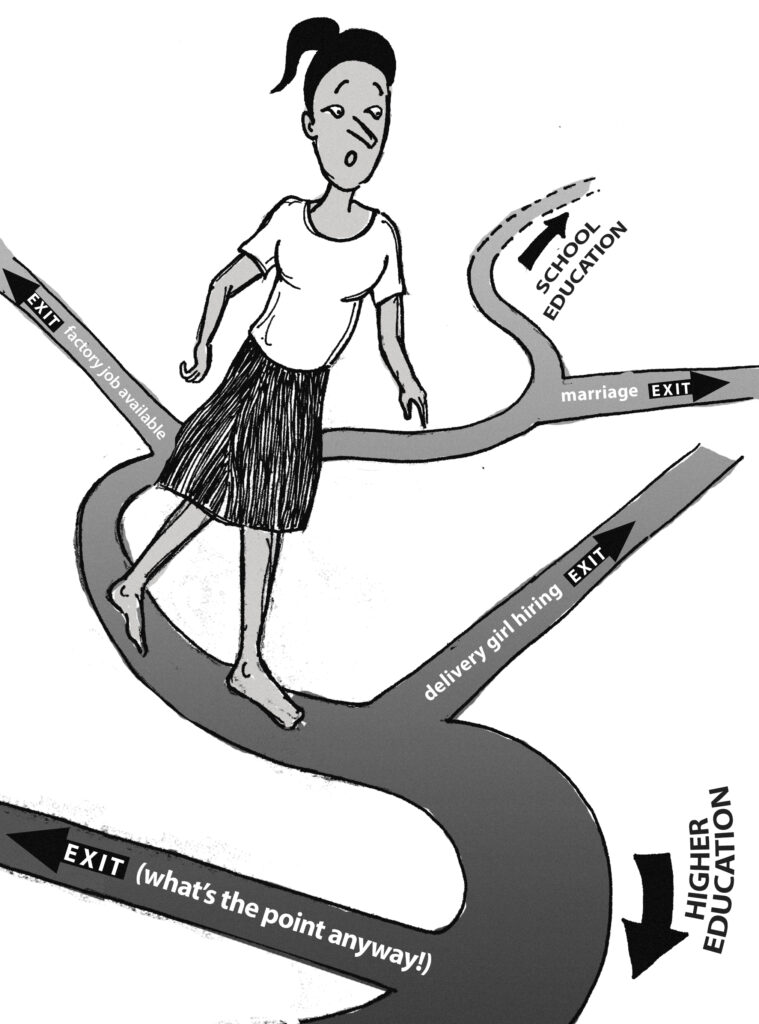

This brings us to the second unsaid assumption that is shared by the document and its enthusiastic supporters. This is regarding the assumption of formal-juridical equality between members of a group in a society fraught with rising inequality, discrimination and segregation. In 1966, the Kothari Commission argued for a Common School System in every locality, virtually arguing that any student, whether the daughter of a Prime Minister or a daily-wage worker, would get the same schooling. The standard of all schools would be improved and the rich and powerful will not be able to maintain their exclusive, elite schools. The assumption behind this was that unless we provide an equal opportunity for all children, they will be left to repeat the histories of their families. Their socio-economic conditions will constrain their development. Nice pleasantries like ‘choice’, ‘flexibility’ and ‘multiple exits’ are indeed beautiful ways for the state to shirk off its responsibility to providing proper and comprehensive education for all, at least till secondary level.

The argument for public-funded education was not conceived as ‘taking care of the under-privileged’. Rather, it was understood as the way forward for the progress of a nation, in line with earlier anti-colonial struggle. It is a fact that only if everybody is given equal opportunity, which includes policies of positive discrimination like reservation and other policies in favour of the marginalized, that the best of the cumulative capabilities of the nation can be brought out and then there can be a more level playing field for students to choose courses and employment. A robust public education would be the way for rebuilding the nation from the wounds of colonial plunder—economically, intellectually and morally.

That did not happen in our country. The egalitarian aspirations of the anti-colonial struggle had pushed the governments to ensure a minimum of public-funded schooling and higher education, a few scholarships, cheap hostels, libraries, laboratories and so on. These, coupled with policies of reservation, played a positive role in beginning to draw in a section of the marginalized into the arena of higher education. The reversal of such policies started much earlier and is speeding up now like never before.

In a starkly unequal society like ours, it is not hard to imagine what will happen if kids (effectively their parents) are given an ‘opportunity to choose’ their career trajectory at the age of 11-14, how that ‘choice’ will be made in reality. Ours is a society where the reality of ‘choice’ is that most people from oppressed castes still end up doing low-paid manual jobs. Patriarchy is so deeply entrenched and dominant over the mobility and sexuality of women that it cripples the aspirations of most women at an early stage, particularly for women from toiling sections. Undoubtedly, the marginalized sections will bear the brunt of this policy, where effectively, state-funding for a robust and comprehensive schooling for all will recede further.

The demand for a common public education is not just for creating a more level playing field for students from diverse backgrounds. It is also for making future citizens aware of the real history and culture of their region, nation and the world, which is integral to the imagination of an informed citizenry and hence of any substantive democracy.

A reversal from this direction is also apparent globally. A new consensus is being forced upon us, in the garb of the argument that private competition will enhance the quality of education. A shift in paradigm, from ‘substantive equality’ to a mere ‘formal equality’, is visible in policy discourse. More precisely, public discourse is being shifted from the paradigm of equality to a paradigm of survival of the fittest. This is not happening due to any sudden change in ‘human rationality’ itself. The neoliberal economic model is hegemonic over society not by virtue of its inherent strength or superior economic rationality. Rather, it is a result of the balance of forces between labour and capital tilting towards capital over the last few decades and the strength of progressive forces worldwide diminishing.

Pressure from the international Communist movement, from workers-peasants’ struggles and anti-colonial, anti-race, anti-patriarchal movements worldwide and the anti-caste struggles in India during the first few decades of the twentieth century beat capitalism into a particular form. To a limited degree, it won workplace protections and social welfare, the rights of local communities over common resources, political freedoms for the individual, a representative-democratic state, norms against social discrimination and a degree of fraternity across nations. The brute force and ideology of capitalism was arm-twisted into coming to terms with the norms of a ‘humane society’, or rather, these pressures from below built what we know today as a ‘humane society’. Capitalism today has been liberated from the baggage of remaining ‘humane’. It is not shying away from happily marrying with fascist social forces to mitigate its crisis.

For a startling contrast, it would not be difficult to imagine that the previous generation of so-called ‘liberals’ in India, like D S Kothari who dared to draft the policy of the Common School System (mentioned above) in 1966, would today find their ideas being called ‘radical’, ‘Communist-like’ or ‘crazy’ by the same people who think of themselves as liberal. Unfortunately, they have internalized that they must retain the middle-ground, distant from either extreme. If they have criticized four government policies, they feel compelled to defend the fifth and reclaim their ‘neutrality’. With the consensus shifting to the right, those seeking to find a middle-ground in policy debates have had to shift rightward periodically. ‘Liberal’—which has become an all-purpose, denunciatory category in our country today—must have the strength to withstand not just verbal and physical attacks by the far-Right forces but also to stand tall and lose friends who are aspiring to join the global elite, if indeed they still choose to stand with the principles of ‘Liberty’, ‘Equality’ and ‘Fraternity’.