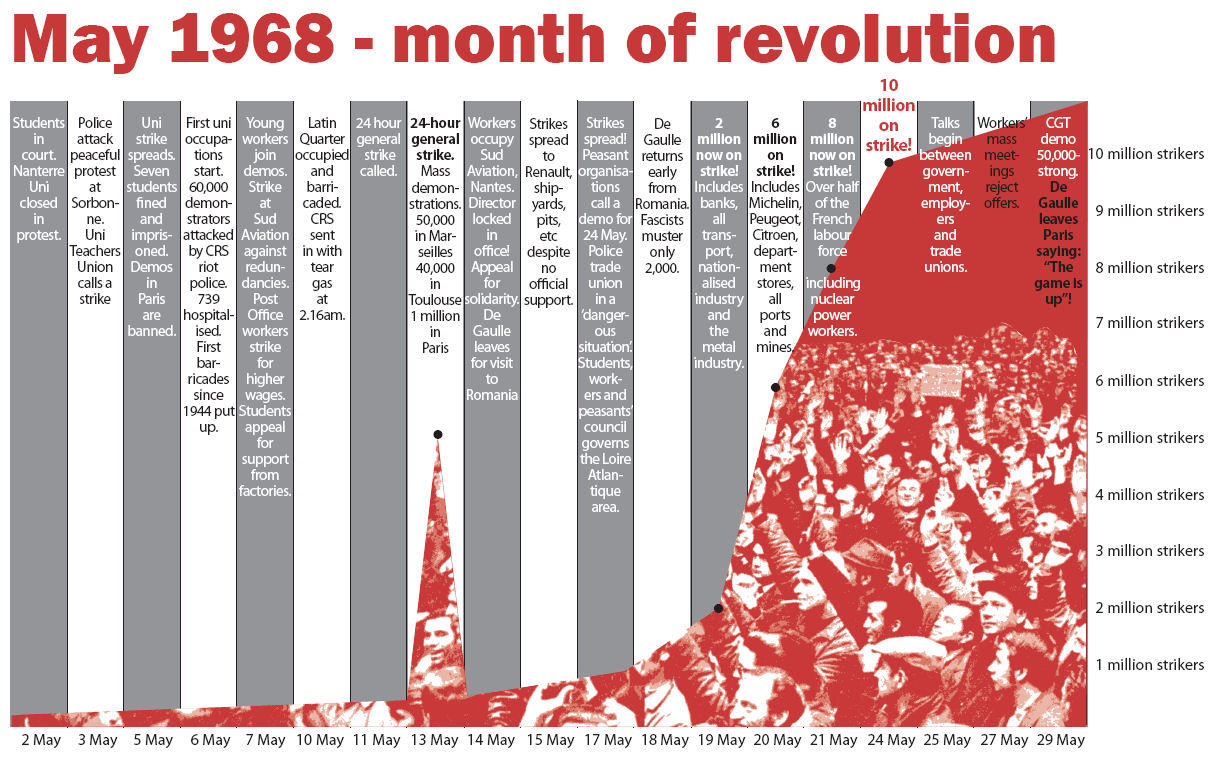

Paris is witnessing another turbulent spring. In the Paris of 1968, as students and workers were prepared for an all-out battle, the French bourgeoisie were left faltered. Let the hundred flowers bloom this time. Prasit Das writes.

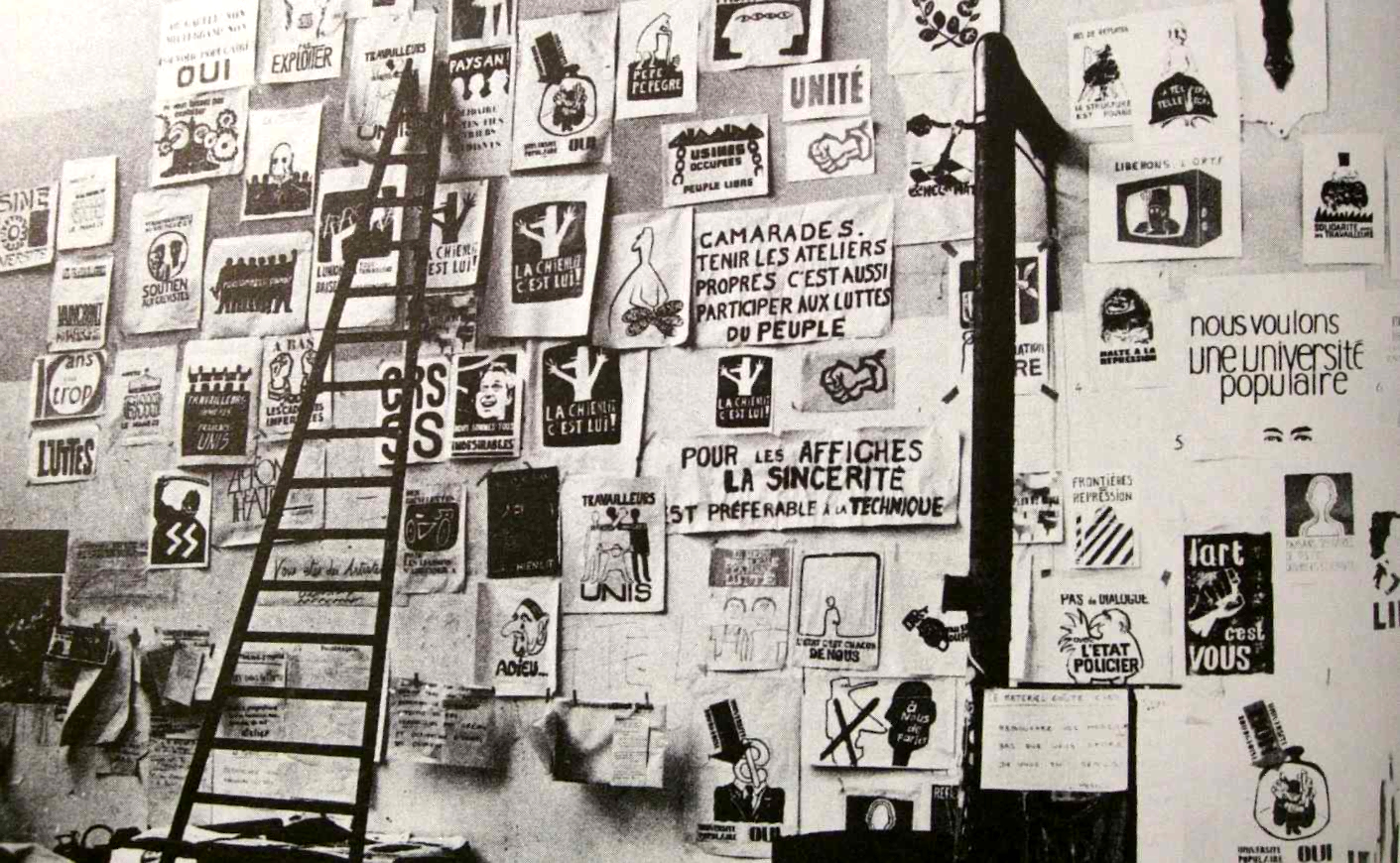

On 5 May last, on the day Karl Marx completed his 200th birthday, The Guardian published a story reporting that the posters prepared by Atelier Populaire, a group of radical artists, during May 1968 were now being exhibited at the Musee de Beaux-Arts in Paris and on sale at a fair hosted by the Royal Academy of Arts in London. According to the story, the posters printed on newspaper rolls supplied by printers on strike in 1968 France were fetching handsome prices at the Royal Academy fair. Not curiously, the title of the Guardian story is: ‘Spirit of ’68 bows to market forces as rebel icons go on sale’.

Now extracting value out of every last bit of rebelliousness is a very old knack of the capitalist society, as has been proved in the case so many icons of rebellion and/or dissent in the past. Fauchon, a luxury Parisian food store, offers its customers a May ’68 brand of tea with ‘the flavor of revolution’. It is rather funny that the British paper found in it an instance of bowing down of the ‘spirit of ’68’ to ‘market forces’, but thought nothing much of the way this ‘spirit’ was being celebrated elsewhere in the country of May ’68.

Source: Internet

As a matter of fact, since the inception of the student protests against the Macron government’s proposed baccalaureate reforms (in reality, a bid to curtail access to university education) in last February and the railway workers’ strike against the government’s privatization bid and the Air France pilots’ strike for an increase in pay in last April, the mainstream western media have been at great pains to define these protests satisfactorily. Consequently, they have taken resort to nice little phrases such as ‘commemorating the anniversary’, ‘rerun of history’ and so on. As if it is the sequel of a historical romance that they are encountering. The students’ protests, on the other hand, denounced such notions from the very beginning. A slogan of the protesters and strikers that was tagged onto the statue at the Place de la Republique square in Central Paris on the occasion of a gathering amply summarizes this spirit: ‘May ’68. They are commemorating, we are starting again.’

The iconic students’ protests that began at Nanterre University demanding some substantial reforms in the educational system and of the university’s policy on inter-sexual relationship on campus in March 1967 and spread like a wild fire all over France next year due to a combination of events represent a constant source of fear and anxiety to the French bourgeoisie. Even Macron’s educational reforms express the same sort of anxiety in some way. One should not forget that thanks to the post-war expansion of the French economy, the middle-class and lower-middle class families were able to send their children to university in a much greater number in the 1960s France. This resulted in a four-fold increase in middle and lower-middle class enrollment while enrollment numbers of the upper class remained stable. This shift in the composition of student population coupled with a remarkable increase in the enrollment numbers of female students (while women constituted 33 percent of the entire student population in 1950, they accounted for 50 percent in 1965-66) did a great deal to transform the political and cultural sensibilities on the French campuses. Here enters Macron with his higher educational reforms.

Source: Internet

While at present every French high school graduate is guaranteed a place at the public university, the new reforms would introduce a tightened selection process for the entry to university. These reforms would also require students to specialize in two major and two minor subjects early at the university as opposed to the present ‘study anything you wish’ system. Clearly, a highly specialized, performance-based and selective higher education system is what is in Macron’s mind. Moreover, these reforms have struck at the roots of the French policy of ‘higher education for all’, a hard-earned trophy of the previous French revolutions. For the French Revolution of 1789, the first one in a long series of revolutions (1830, 1848, 1871, and 1968), declared unambiguously: ‘End all privileges’. And it does not take the brains of a genius that these reforms have been designed to lessen the number of claimants in higher education. Or, shall we say, in order to prevent another May ’68?

Source: Internet

Seems too far-fetched? Well, I am not trying to suggest that preventing another May ’68 is the sole motive of Macron and his colleagues behind introducing the baccalaureate reforms. Certainly a broad neo-liberal design is at work here. In fact President Macron could not be more explicit in this regard when he said that the new reforms would prepare the students better for the job market. Combine this with the French government’s privatization bid in the railways and the pension reforms, and you have a neatly planned neo-liberal design to ‘speed up the economy’ congenial to a global design. But May ’68 is an evergreen poisonous tree in this neo-liberal garden where everything seems so lovely.

Nicolas Sarkozy, one of the recent predecessors of Macron, admitted as much when, during his election campaign in 2007, he wanted the ’68 legacy to be ‘liquidated’ once and for all. In fact, a well-trained social scientist could not have expressed some of the principal ideas of the May ’68 legacy better than Sarkozy who lashed out at the generation that had said “that authority, good manners and respect were out of fashion; that nothing was sacred, nothing admirable; … that nothing was forbidden”. Sarkozy’s hostility towards May ’68 and everything it stands for is well-known. Allegedly, a 13-year-old Nicolas Sarkozy had to be restrained by his mother from joining the infamous right-wing pro-De Gaulle march up the Champs-Elysees in 1968. But his words echo a deep fear of the French bourgeoisie.

Source: Internet

Why are the French bourgeoisie so much afraid of May ’68? Analyzing this fear, the French philosopher Alan Badiou has concluded that what is in fact haunting the regime under the name of ’68 is the proverbial specter of communism, ‘in one of its last real manifestations’. As Badiou has observed, Sarkozy and the class (well well, the tabooed word at last!) he represents would prefer even the ‘hypothesis of communism’ to become unmentionable. Now what is this hypothesis of communism? It means, to quote more extensively from Badieu, “…the fundamental subordination of labor to a dominant class – the arrangement that has persisted since Antiquity – is not inevitable; it can be overcome. … that a different collective organization is practicable, one that will eliminate the inequality of wealth and even the division of labor. … The existence of a coercive state, separate from civil society, will no longer appear a necessity….” May ’68 inspired belief in the possibility of this impossible; moreover, it taught the world that even this impossible could be demanded on the barricades. And hence it represents the worst nightmare of the French bourgeoisie.

There is no dearth of the commentators in the mainstream press who will tell you that the legacy of May ’68 is nowhere to be found. In fact, Raymond Aron’s book on May ’68 is called La revolution introuvable, which in English means The Nowhere-to-Be-Found Revolution. The French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy, on the other hand, has argued that the reason there is no possible legacy of ’68 is that ’68 never ended. One often gets to hear talks such as ‘the sixties were a different time’, ‘the shadow of the anti-Vietnam War protests and the liberation war of Algeria loomed large over ‘68’, ‘so many things were happening around the world’ etc. The moral is short and simple: gone are the good old days when people thought revolution possible and/or this not just the right time. I wonder what will the apologists of the present order, who always want to situate the moment of revolution in the past, say now with half of Europe burning with rage against an aggressive capitalism, with thousands of workers (yes, literally) marching across the continent on last May Day and people rejecting the neo-liberal model everywhere. A deep discontentment with society, with the present order, with powers-that-be is manifesting itself in different ways itself across the globe, be it in the form of students’ protest against the unjust gun laws in the USA, or be it the workers’ protests demanding better pay and better working condition in Germany. This feeling that things are not going right has been historically crucial in any revolution. As I have said earlier, memorabilia and specimens of rebellion indeed fetch good money in a marketplace ruled by the conditions of capital. But a real rebellion will frighten the ruling class out of their wits as it is capable of abolishing those very conditions.

Distant view of crowds during mass demonstration of students and workers during general strike in Paris on May 13, 1968. Picture was taken on Rue De Turbigo with the Place de la Republique in the background. (AP Photo/Eustache Cardenas)

The spirit of the revolution (Do you mind my calling it a revolution? Well, I just cannot help it.) that demanded sexual liberation and an education system free of state intervention and social conservatism, that brought students and workers together on the streets, that showed the world that a rally of 50,000 students could be brought out without any centralized, party-based mobilization, that showed that the coexistence of groups of various political colors (Anarchists, Maoists, Troskysts, and Situationists, to name a few) was possible in a single movement, that taught the world that irreverence should be the spirit to greet capitalism, that turned the bourgeois culture upside down in all its forms and gave birth to a number of era-defining cultural currents is resurfacing once again. Paris is witnessing another turbulent spring. While the students and workers were prepared for an all-out battle, the French left faltered in 1968. Let the hundred flowers bloom this time.

Prasit Das is a freelance journalist.