V. Geetha

In this summer of our discontent, with fury raging on our campuses and streets, I would like to take a detour through nineteenth century lives and ideas, so as to return to the present, with an enabling sense of history. I start by calling attention to the way knowledge came to be reconceptualised in this period.

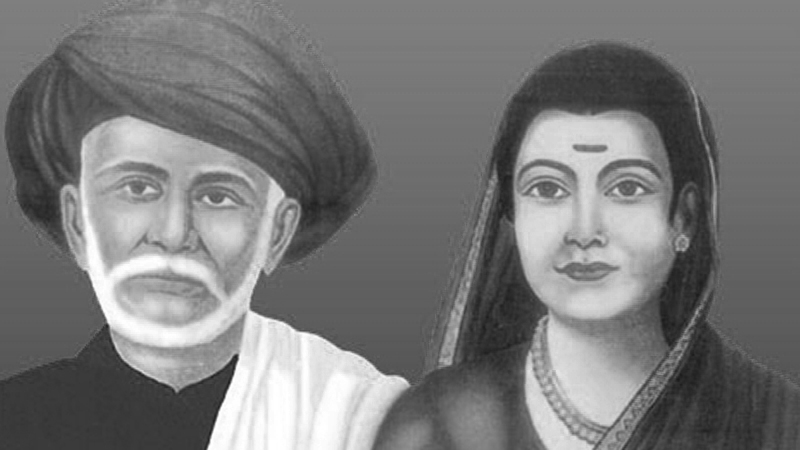

As we all know, Mahatma Phule and Savitribai Phule were amongst the first educators to start a school for Mahar and Mang girls. These schools did not last long, but they clearly left a mark on those that attended them – as is evident from a letter by one of Savitribai’s students, 14 year old Mukta Salve, which was published in the weekly, Dnyanodaya. In it she called attention to what ailed her society: forced ignorance, poverty and caste resentment directed against the so-called untouchables. Education was important in this context – it would heal a wounded self and render it ‘moral and righteous’.

Mahatma Jyothiba and Savitribai Phule

Clearly she had learned her lessons well, and perhaps not only within the classroom. The school that she studied in was part of a larger public space, and one which saw Mahatma Phule and Savitribai speak and act against the caste order. Like other anti-caste thinkers – Iyothee Thass, Periyar and Dr Ambedkar – Phule viewed education as a mode of attaining critical knowledge, that which opened the third eye of discernment, and made for a rational and just analysis of the world. The education that children received in the schools he founded therefore was rather unique – and made for confident and self-assured expression as much as it nurtured literacy.

The quality of voice that is evident in Mukta Salve’s letter is a measure of the sort of consciousness these schools enabled into existence. What constituted this consciousness and how might we understand its relevance to our times?

From the mid-nineteenth century onward, Indians who had the chance to go to school and university could expect to follow debates in the realm of science and read dissenting literature, which included anti-religious polemic and radical political tracts. In the Madras province, for example, a remarkable journal was published in the 1880s, called The Thinker (the Tamil version was Tattuva Vivesini) by an organisation called the Hindu Freethought Union (it was also referred to as the Madras Secular Society). These journals featured articles on science, and took up the cause of the ‘scientific world view’ – which advocated a form of knowledge based on evidence, reasoning and experiment. However the scientific view was not restricted to understanding observable, physical phenomena alone. It was understood as a form of knowledge that could just as effectively challenge religion, religious dogma, custom, dicta and social habit. The Thinker published extensive critiques of superstitious practices, faith-based rituals and what its editors considered unreasonable and obscurantist beliefs.

A related approach to knowledge that emerged during this period had to do with a systematic study of the past. The past, it was argued, is neither what is handed down to us nor memory that is revered as custom and habit. It is knowable through rational means, and through an analysis of what time has left behind, including material objects such as statues and monuments and diverse texts, including royal proclamations, edicts and notices. Such knowledge of the past is not to be undertaken in a vacuum – rather it requires an understanding of how change and progress happen.

An interest in and fascination for history was not restricted to formal educational spaces. Rather, a study of the past appeared important to all those who felt enslaved by history and desired to free themselves from it. In the event, those who took to historical research and reasoning, even if they were not formally trained in the new discipline, came to advance startlingly new ways of looking back. In other words, historical knowledge was made coeval with social action (See Gail Omvedt, ‘Colonial Challenges, Indian Responses and Buddhist Revival’, in Buddhism in India, New Delhi: Sage, 2003, pp. 217-242).

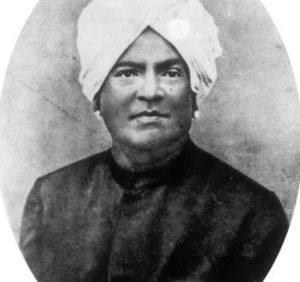

Importantly, for Phule, the Madras Secularists and for those possessed of the historical spirit such as Pandit Iyothee Thass, critical knowledge had to also help remake social relationships. The staunchly scientific Madras Secularists urged the cause of cooperation. For his part, Phule aligned knowledge to truth, arguing that the latter was one that grounded men and women – stripurush – in a network of mutual rights, respect and responsibility. Iyothee Thass insisted that critical knowledge had to heed the mandate of compassion, and wrote of the importance of jeevakarunya or compassion towards all of creation, a value that he posited as the very opposite of the animus of caste.

Pandit Iyothee Thass

It seems to me that this emergent sense of knowledge, at once scientific, critical and social, and bound to history, provides a context for us think of how we might re-imagine the university in our times. In what follows I present two examples of how new knowledges shaped social critique and action and were, in turn, shaped by them.

Amongst Mahatma Phule’s writings, those which featured in the journal Satsar are important (See G. P. Deshpande (Editor), Selected Writings of Jotirao Phule, New Delhi: Leftword, 2002, pp: 203-223). These were explicit in their intent, defending the great educator Pandita Ramabai’s conversion to Christianity and upholding the writer Tarabai Shinde’s acute, provocative and fierce criticisms of male sexual and social hypocrisy in her remarkable Stri-Purush Tulana (See Rosalind O’ Hanolan (Editor), A Comparison between Women and Men: Tarabai Shinde and the Critique of Gender Relations in Colonial India, Oxford University Press, 1994). This latter text had earned the ire of even some members of Mahatma Phule’s Satyashodak Samaj, and it was this which impelled him to defend Tarabai’s work. The support he extended to Pandita Ramabai was equally remarkable, and had to do both with his lifelong criticisms of Hindu dogma, Brahmin intellectual pretensions and hostility to reform and social change; as well as his keen sense of what the rebellion of Brahmin women would bode for caste society – nothing short of a rejection of the shastras and an abandoning of the faith (For a detailed account of Pandita Ramabai’s life, see Uma Chakravarti, The Rewriting History: the Life and Times of Pandita Ramabai, New Delhi: Zubaan, 2013 (originally published, Kali for Women, 1998).

The polemic against brahmins – and some shudras – who castigated Ramabai and fellow shudras who took up against Tarabai was deliberately crafted. Cast in the form of conversations, a mode favoured by Phule and which allowed him to work through doubts, confusions and ambiguities with regard to contentious matters to do with faith and history, the polemic was wide ranging.

The defense of Ramabai’s conversion becomes the occasion for a robust critique of Hindu social reform. Reform, argues Phule, must start with discarding Hindu scripture and canon, as these have been traditionally assembled and interpreted. Secondly, shudras and atishudras (Phule used these as essentially compound words, thereby assigning them a coeval shared presence in the Hindu social order) must be restored to a state of dignity. It was not enough to claim that they too were aspects of an all-pervasive formless brahman, as organizations such as the Brahmo Samaj were wont to. Such claims could serve no useful purpose, except that they seek to assimilate all those who were currently socially degraded state into an unreformed Hindu faith. Mahars and Mangs needed education, not benevolent charity, for it was only learning that would enable them to engage critically with Brahmin intellectual authority and its essentially duplicitous core.

Phule also points out in this context, that the mere incorporation of shudras within Brahminical texts, including the assigning of a shudra identity to Vyasa does not quite address the problem of Mahars and Mangs, or for that matter, the fate assigned to shudra women. For even if Vyasa’s mother was shudra, his father was still Brahmin and this reckoning through the father served the Brahmin cause well. Further, he asks, “Is there any proof in your books about the brahmans having incorporated into themselves the progeny of a brahman woman and an atishudra man?”

In his defense of Tarabai, Phule trains his critique on male hypocrisy on the one hand, and on the other hand, called attention to the power invested in powerful wealthy and ruling class men – and indicated that women of such families and communities did not possess the authority and force to do all that men from such backgrounds could do. From this point onwards he launches into a scathing, powerful critique of male proclivity for both individual and social violence, producing as it were a short and searing history and critique of war, slavery and inhumanity. Interestingly, his calling out men on their hypocritical responses to Tarabai simultaneously positions women as less prone to such behavior; and his rejection of war and violence separates out women, even of royal and rich families, from the havoc wrought by their men.

In these addresses, Phule does the following: he works through the complexities of male sexual authority, the relative powerlessness of shudra-atishudra men in society, and their relative authority within their families; he is keenly aware of the exceptional status of the Brahmin woman, when compared to what shudra and atishudra women endured, but he was also aware of her essential precarity within her own context, a fact that moved him enough to start a foundling home for the children of Brahmin widows. In short, his defense of the two articulate women who, in different ways, had challenged the Hindu social order and male privilege hinged on his acute sense of what kept both in place. The sexual and familial subordination of women, as we know, is fundamental to the sustaining of caste hierarchy and should women rebel against both familial and caste authority, the system does begin to unravel

It seems to me that this complex perspective, communicated through the persona of the disarming Tatya (the persona adopted by Phule in his dialogues as featured in Satsar and elsewhere), who is both severe as well as kind, holds out a model of mentorship that is scathing and consistent in what it criticizes and teaches. Yet this model is also fundamentally compassionate in how it engages with injustice and suffering. Intellectual acumen, polemical vigour and a deep and conscious sense of what the powerless and the precarious endure in their relative contexts – there is something here for teachers to think through. Often it is the absence of the last that compromises all else – something which we witness in the anguished responses to students who feel betrayed by those they perceive as progressive. For all his anger against brahmins, Phule is essentially driven by his sense of what atishudras and shudras endure, and the balance he achieves between a keen and tender awareness of social suffering and indignation at social wrong holds important lessons for all of us, engaged in the business of teaching and communication.

I now turn to Iyothee Thass: he lived and worked – as a writer, journalist and siddha healer – in colonial Madras (For an account of his life and work see, G. Aloysius, Religion as Emancipatory Identity: A Buddhist Movement Amongst Tamils Under Colonialism, New Age International, 1998). An acute observer of life and times, as these unfolded under the aegis of India’s colonial rulers, he welcomed the British, for they appeared to observe no caste norms, did not mind eating beef and kept company even with the so-called lowborn. Further, they did not seem to be motivated by prejudicial thoughts and their courts of justice heeded no authority external to their own. Most important, the British had made available a public culture of learning that was nominally, at least, available to all and thus in a single stroke undermined the Brahmin’s control over knowledge.

Emboldened by the context that he found himself in, and inspired by the late nineteenth century revival of Buddhism in parts of India and in Sri Lanka, Iyothee Thass, like several others of his time, and of other times, took to the teachings of the Buddha. He also took to glossing Tamil literary texts – to construct a history of Buddhism which, he argued, had been eclipsed by the success of Brahminical Hinduism.

For Iyothee Thass acts of critical knowledge, including those he had undertaken, are essentially ethical acts. They did not wait upon divine sanction or the endorsement of brahmins and their texts. Rather those who sought to know the nature of reality or history did so on the understanding that they were acting on their own, and were responsible for their mode of reasoning and understanding. This was also why thought had to be ‘right’, not coloured by prejudice or privileges derived from birth.

Significantly, Iyothee Thass likens the acquisition of knowledge to the art of healing: just as a good healer enquires into the conditions and cause of the illness, so does a responsible human being seek the meaning of what ails him. And just as a healer does not seek to rest his responsibility of knowing on another, but trusts his own diagnosis, so does the good Buddhist trust his own powers of enquiry. Importantly,

Thass also locates knowledge in what people did, and not merely on what was said, recited or remembered, or what was made available in texts. Knowledge inhered in labour, for instance and here Thass sought to redefine caste labour. Caste occupations, he notes, are valuable forms of labour that had been degraded. Such forms of labour do not have to do with birth, rather they are universal and had to be understood as what human beings undertook in diverse geographies. Those who performed such labour “knew” reality in a useful, productive sense. Their labour, Thass insists, and the knowledge it encodes, is different from and must be contrasted with the “really useless knowledge of the Brahmins”, as present in their endless interpretations of scripture, custom and law.

Thass thus offers an expansive vision of knowledge: knowledge rests on critique that the individual learner learns to cultivate. It is also not limited to the labour of thought and what that does to consciousness. Rather it inheres in doing, in acts of production and exchange.

It seems to me that Thass’ definition of ‘useful’ and ‘useless’ knowledge is apposite to our concerns today. Our commonsensical sense of education, especially knowledge generated in institutions of learning, is that it betters, tempers and uplifts the learner. Knowledge is seldom seen as something that might be gleaned from what students bring to the classroom. With dalit and bahujan students coming into higher education in increasing numbers, have we responded imaginatively to their needs and claims? To the knowledges that are central to their life-worlds?

If we are indeed sensitive in this regard, we would effectively reimagine methods of understanding and processes of learning. We would learn to align thought with the long history of labour and artisanal practices, with experiences of cooperative and collaborative work that keeps a working class and subaltern neighbourhood together. Most crucially, we would come to an understanding of knowledge as active and dynamic, and inherently transformative, as something we do, make, create, and not as something we learn by rote, and which requires us to remain and interpret within the limits of what is given to us.