Places like Shaheen Bagh, Park Circus, and Rajabazar have thus far been off our political maps, where one only takes out a rally or holds a program, or goes to collect ‘data’, when one is to engage with what is construed as ‘Muslim’ issue, writes Jhelum.

Spaces have their own stories, their own archives of histories. Shaheen Bagh today has almost become a pilgrimage site. If one visits in the afternoon or evening, one can only see colourful heads huddled together beneath the shamiyana, raising fists in the air while echoing slogans that are being chanted on the stage. The songs and slogans, though, have spilled onto the streets, in the local tea shops on the road to Jasola Vihar-Shaheen Bagh metro station, in front of what had been the Shaheen Bagh bus stop, just beneath the footbridge. Conversations on politics, friendly banter, jam sessions, and reading corners have all come together in a cacophony of protest, in a carnival of resistance, creating different stories, some new, some old, some uncertain.

But spaces also carry with them stories of histories. The shooting at Jamia Milia Islamia and the open firing at Shaheen Bagh and Jamia have been testimony to that. For many, they brought back memories of the Batla House encounter of 2008, and made afresh memories of the recent attacks in Jamia Milia Islamia on 15 December, 2019, where the police fired at students, brutally attacked them, and then made them leave their own campus with their hands raised in the air as ‘suspects’. The resurfacing of these memories serves as a reminder of how these spaces have always been precarious, how lives in these spaces have always been dispensable. It seems like the stench of gunpowder had never really left the area, and neither did the sense of dread, or the humiliation of persecution. Every story thus embeds in it other stories, other histories – histories of being a ‘suspect’, histories of being lesser citizens, histories of being pushed to shrink one’s own identity to keep together the secular fabric of the country.

Liberal and mainstream Left politics too have either shied away from engaging with Muslim people or have seen them mostly as ‘subjects’, as people to be rescued, and ‘taught better’. Places like Shaheen Bagh, Park Circus, and Rajabazar have thus far also been off our political maps, where one only takes out a rally or holds a program, or goes to collect ‘data’, when one is to engage with what is construed as ‘Muslim’ issue.

For a visitor, perhaps the first realisation of how spaces can also be ‘untouchable’ dawns when one tries to book a cab/bike ride to or from Jamia Nagar. Negotiations begin as the voice on the other end says, “Wahaan pe danga hota hain, hum nahin jaate (Riots happen there, we won’t go),” or just simply cancel, because some areas are off our regular maps, some areas are demarcated as ‘dirty’ or, as what ‘secular’ India terms it, ‘mini Pakistan’. Shopkeepers in Shaheen Bagh, though, are unfazed. Residents of the area have become so used to being ‘invisible’, being ‘untouchable’, that they will nonchalantly tell you to walk towards the other side, to the other end of the metro to book your ride. “Yahaan pe nahin aate (They don’t come here),” they tell you with a straight face. These are spaces where perhaps the only government buildings that crop up more are police stations, where corporation waste disposal vans can afford to skip a day, where even with such a large population there are no parks or playgrounds, where public land can easily be given off to plastic burning plants without the rest of the city batting an eye. However, this practice of ‘untouchability’ has not been the sole prerogative of the far right. Liberal and mainstream Left politics too have either shied away from engaging with Muslim people or have seen them mostly as ‘subjects’, as people to be rescued, and ‘taught better’. Places like Shaheen Bagh, Park Circus, and Rajabazar have thus far also been off our political maps, where one only takes out a rally or holds a program, or goes to collect ‘data’, when one is to engage with what is construed as ‘Muslim’ issue.

The visibility of Muslim women in Shaheen Bagh, in Park Circus, in Nagpada, in Seelampur wearing all their religious markers, asserting their identities, thus, not only breaks our so far dearly held notions of ‘secularism’ to make way for newer understandings of ‘secularism’ – secularism that is truly hinged on assertion and acceptance of all religions.

This is perhaps where Shaheen Bagh intervenes. It not only brings one to spaces where one would otherwise choose not to tread, but also makes those spaces a site of learning and more importantly, unlearning. The centering of the movement on Muslim women’s political subjectivity forces us to question our privileges, our own political Brahminism. When the ‘dadis’ of Shaheen Bagh, Mehrunissa, Bilkis, Rafika and others, greet you with “Acchaa hua is bahaane aap log yahaan aye, aapse mulakat hui (It’s good, at least this has made you come here, we got to meet you)”, it also becomes a moment of reflection on the black spots of our own political maps, on the blanks in our own understandings of spaces. One is reminded of how in Bengal, rationalist organizations, even some non-parliamentary Left organizations, have refused to walk in the same rally with Muslim organizations, how Muslim organizations have had to pass the litmus test of ‘secularism’ to be included in joint anti-fascist forums. One is reminded how even sometimes back one would see ‘progressive’, ‘liberal’ people expressing discomfort at walking with men with beards and topis, or women in hijabs, or label such mobilizations as ‘Islamic’ or ‘fundamentalist’. The visibility of Muslim women in Shaheen Bagh, in Park Circus, in Nagpada, in Seelampur wearing all their religious markers, asserting their identities, thus, not only breaks our so far dearly held notions of ‘secularism’ to make way for newer understandings of ‘secularism’ – secularism that is truly hinged on assertion and acceptance of all religions.

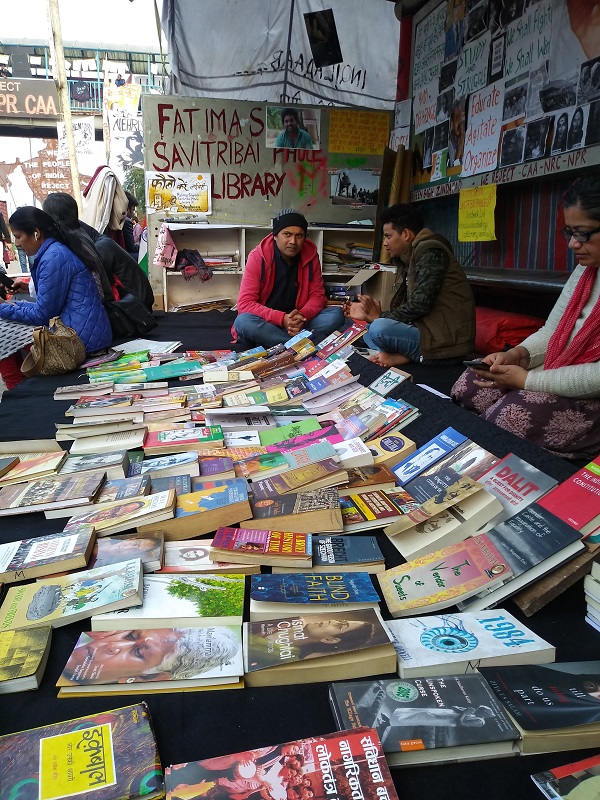

It is in this context that the spilling over of Shaheen Bagh onto bus stops, tea shops, libraries, and highways becomes so supremely important. I ask Mehrunissa, one of the women who have now become more known as a ‘dadi’ of Shaheen Bagh, “Why chakka jam? (Why the blockade?)”. Pat came Mehrunissa’s reply, “Nahin to koi humara sunta nahin hain… agar isse nahin hua to pura Dilli mein chakka jam karna hain (Otherwise no one would have listened to us… if this doesn’t work we’ll bring all of Delhi to a standstill)”. Even the first visit to Shaheen Bagh or Seelampur makes you realise that it is the protest sites that are rehabilitating these spaces on our map. It is the road blockades, the occupying of public spaces that are forcing us to take cognizance of people who have been so far considered ‘unauthorised’, of people who have been so far invisible to us. It is the roadblock that made Shaheen Bagh enter our conversations in autos, metros, buses, at dining tables, on college campuses, in office canteens. Shaheen Bagh too spilled over onto the bus stop that became the Savitri Bai-Fatima Sheikh library, stacked with ‘seditious’ books and posters, beside the footbridge that bears the marks, sketches, and etches of resistance, remembering and reminding us of things we cannot look away, in the porch of a shop that has now become home to kids in Shaheen Bagh where children can walk in, read a book, draw, make posters.

This spilling over is perhaps what unsettles the regime most as it defies their neatly demarcated spaces, their ideas of ‘authorization’, their notions of ‘permission’ as well as our notions of the ‘political’. It is like the ‘velivada’ of Rohith Vemula – the site that still haunts the citadels of the Brahminical state, so much so that the authorities keep tearing it down, only to find it rebuilt. Shaheen Bagh, Seelampur, Park Circus Maidan, Ghantaghar, Shanti Bagh, Mumbai Bagh, Mumbra – these are the ‘untouchable’ ghettos that we are now forced to visit, to learn from, and to take note of. A poster made by one of the children in Shaheen Bagh reads, “Kuch din to guzaariye Shaheen Bagh mein (Come, spend some days in Shaheen Bagh)”. As India prepares itself to become a police state, where one’s existence is made legal provided one is able to ‘show their papers’, it is these sites that are rebuilding our notions of citizenship, our notions of ‘secularism’. Libraries and reading corners that do not require membership, where anyone can just drop in and read; makeshift schools where one need not fill up paperwork to learn; a children’s library where children demand ‘papers’ to make posters; a big board set up as an ‘unemployment mirror of India’ where people put up their ‘papers’ to chart unemployment; a gallery of photographs documenting police atrocities captioned ‘Sab yaad rakha jayega (All of this will be remembered)’ – these sites are not only forcing us to re-examine our contracts of citizenship, but also making us rethink the politics of ‘documentation’. As one sees the children paint posters of women protesting, as one sees a poster made by a student of class 7 say, “Azaadi ke geet ga liye par Kashmir ko bhul mat jaana (While singing songs of freedom, please do not forget Kashmir)”, or when one talks to Alika and many other young girls who comes to these protests everyday from school, one is also reminded of how our notions of ‘protective childhood’ are constructed through our privileges, as one listens to women share their difficulty in explaining to them why the ministers ‘hate’ them, one is forced to interrogate our own privileged notions of ‘innocence’.

… as Hindutva footsoldiers fire at Jamia, young Muslim girls in Shaheen Bagh fill the streets at 3 AM with the slogans “Jamia tere khoon se inquilab aayega”…

Thus, as the Supreme court expresses its concern over why a four month old baby was out there at a protest site, women build makeshift creche’s around the protest sites; as the paid media goes berserk over children being ‘radicalised’ and ‘indoctrinated’, children who have so far grown up in these velivadas make sense of our Islamophobia, paint their ideas of a ‘nation’, their ideas of resistance; as Hindutva footsoldiers fire at Jamia, young Muslim girls in Shaheen Bagh fill the streets at 3 AM with the slogans “Jamia tere khoon se inquilab aayega (Jamia, your blood will usher in the revolution)” ; as the police spray unknown chemical substances in a protest rally of Jamia students, and as CCTV footage lays bare the brutal way police had entered the university and beat up students who were reading in the library, the protesters at Shaheen Bagh and Park Circus build makeshift libraries where people read and listen to stories of people in Kashmir, in Pakistan, in India, stories of oppression and stories of resistance; as we go to these protest sites to ‘teach’, those who we have so far thought of merely as ‘subjects’ of revolution, force us to take a back seat and take note and learn ethics of solidarity, of allyship and most importantly, friendship. One of the refrains that remain from the conversations in Shaheen Bagh, in Seelampur is about friendship, about love. As one of the women in Seelampur jokes, “Modiji ne yehi ek acchha kaam kiya hain, is silsile mein bahut saare naye dostiyaan diyi hain (One good thing that Modi has done is made us all friends)”.

As the state tries to reinforce borders, bloodlines, and family structures, Shaheen Bagh, Park Circus, Seelampur, Mumbai Bagh, Ghantaghar emerge as sites of friendships, queer kinships that keep defying, messing up our hetero-patriarchal notions of ‘family’.

It is these friendships, forged through the spilling over of the protests from neatly ‘authorised’ spaces of Jantar Mantar or Azaad Maidan to Shaheen Bagh, Seelampur, Nagpada, Mumbra, of people from the demarcated ‘ghettos’ to highways, of women from their assigned domestic spaces to the streets, of children from adult sanctioned spaces to protest sites – that has unsettled the powers that be. As the state tries to reinforce borders, bloodlines, and family structures, Shaheen Bagh, Park Circus, Seelampur, Mumbai Bagh, Ghantaghar emerge as sites of friendships, queer kinships that keep defying, messing up our hetero-patriarchal notions of ‘family’. In times when our hitherto known structures of democracy are failing, it is this politics of friendships forged through learning and unlearning, through navigating differences, through setting newer terms of allyship, through newer negotiations (where the terms would not be set by the privileged), through newer modes of disruption and making noise, through newer ways of remembering, that might help us sail through.

Jhelum is a researcher and involved in activism. Views expressed in the article are authors own.

All photographs used in the article are by the author.

Immensely thought-provoking. The writer really gets into the heart of the Shaheen Bagh struggle.