As the standoff in Rajasthan’s Hanumangarh district enters a critical phase, the struggle for farmers of Tibbi tehsil is no longer only against an ethanol plant. It has become a larger battle over who decides the future of land and water—and whether rural livelihoods and fragile ecologies can survive the march of an ecologically destructive, corporatised model of industrial “development.”

Groundxero | December 17

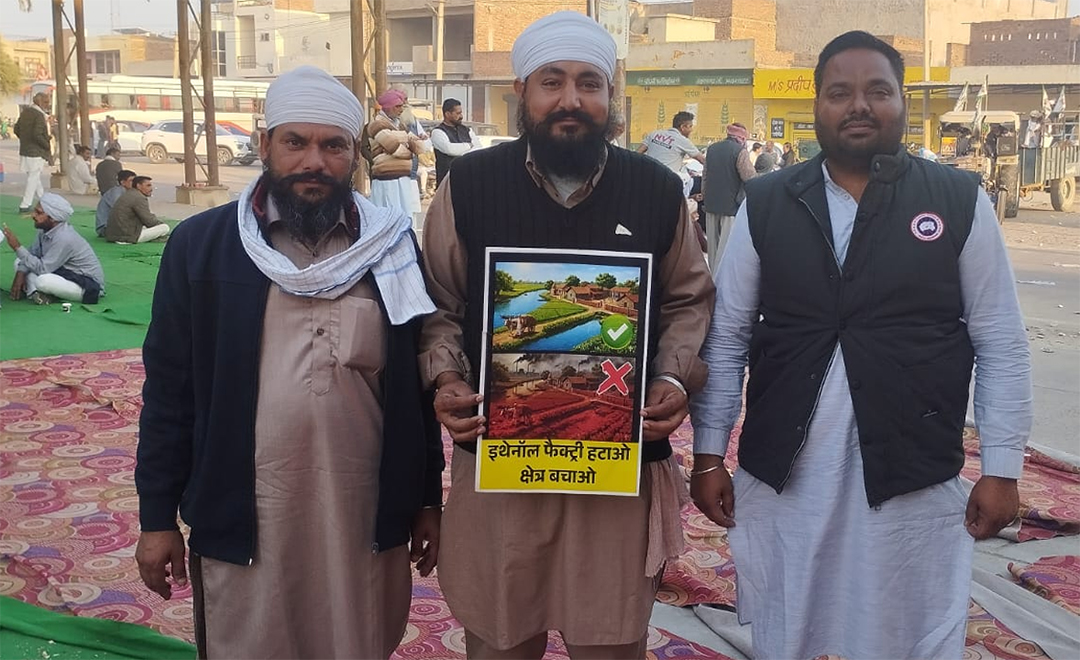

Thousands of farmers, farm workers and rural residents gathered at a Mahapanchayat at the grain market in Hanumangarh Junction on Tuesday, issuing a 20-day ultimatum to the Rajasthan government to cancel the MoU signed with the ethanol company and withdraw all cases filed against protesting farmers. The Mahapanchayat concluded peacefully, but with a clear warning: if their demands are not met, the agitation will escalate.

Long before the Mahapanchayat began, farmers started arriving at the grain market from villages across Hanumangarh and neighbouring districts. Despite prohibitory orders, internet shutdowns and the area being turned into a fortified police zone, the message was unmistakable—this was not a movement that could be subdued through administrative restrictions.

For over seventeen months, farmers of Tibbi tehsil in Rajasthan’s Hanumangarh district have opposed the construction of an ethanol factory in Rathi Kheda village. What began as quiet opposition to a so-called “development project” has hardened into a sustained resistance shaped by fears of livelihood loss, ecological destruction, administrative indifference and repeated state repression.

The factory at the centre of the storm is a 1,320 KLPD grain-based ethanol plant with a 40 MW co-generation power facility, promoted by Chandigarh-based Dune Ethanol Private Limited. The company purchased around 40 acres of farmland in 2020. In June 2021, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change granted environmental clearance to the project.

An Ethanol Factory in a Fertile Agricultural Belt

The Chandigarh-based Dune Ethanol Private Limited purchased 40 acres of farmland in 2020. On June 16, 2021, the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEFCC) granted clearance for a 1,320 KLPD grain-based ethanol plant with a 40 MW co-generation power facility. The company assured the provision of local employment and maintains that the project will support the Union government’s Ethanol Blended Petrol (EBP) programme by reducing fuel imports and boosting ethanol production.

Initially, many villagers were persuaded by promises of jobs and prosperity. But by early 2024, opposition began to crystallise as farmers studied the environmental footprint of ethanol production and realised the scale of extraction involved. What troubled them most was not just pollution, but the possibility that land sustained for generations could turn into wasteland.

Tibbi’s agriculture thrives on water from the Indira Gandhi Canal. The area forms part of the Ghaggar basin—an intermittently flowing river system known for floods and ecological fragility—where farmers grow two to four crops and practise animal husbandry. It is one of the few green belts of Rajasthan and sustains the livelihoods of lakhs of people.

Locals fear that ethanol brewing will deplete groundwater, industrial effluents will contaminate canal water, and poisonous ash will worsen air pollution. They point to the example of Zira in Punjab, where a sustained peasants’ protest recently forced the shutdown of a similar ethanol plant over pollution concerns.

From Peaceful Protest to Resistance

For over the last 17 months, farmers in this canal-dependent agricultural belt have peacefully opposed the ethanol factory, arguing that it poses severe threats to groundwater levels, soil fertility and crop yields through potential environmental pollution and ecological destruction. The Ethanol Factory Hatao Sangharsh Samiti has led dharnas, marches and submitted memorandums, but claims authorities dismissed their pleas without site inspections or environmental impact reassessments. The peasants accused the BJP-led state government of consciously promoting corporate interests, ruining land, soil and water bodies that provide food and livelihoods.

The protests intensified in July 2025 after the company began constructing a boundary wall at the site. The last discussion with the administration was scheduled for November 25; however, ahead of the meeting, on November 19, a massive police force arrested 12 key leaders of the agitation, and construction resumed under heavy police protection. The arrests shattered any remaining trust in the administration, triggering fresh anger among the peasants.

A farmers’ gathering was called on December 10 to decide the future course of the struggle, drawing thousands of peasants from about 15 villages of Tibbi tehsil. Farmers held a large protest outside the Tibbi Sub-Divisional Magistrate’s office, demanding cancellation of the project. The protest spiralled out of control after police baton-charged the protesting farmers. Enraged farmers broke through barricades, marched with tractors towards the factory site at Rathi Kheda and clashed with security forces. Tear gas shells were fired, lathi charges followed, and more than a dozen vehicles—including a police jeep—were set on fire.

A large number of farmers, as well as policemen, were injured in the clashes. Local Congress MLA Abhimanyu Poonia—who had joined the agitation alongside MP Kuldeep Indora and farmer leaders from Haryana and Punjab—sustained injuries and was hospitalised.

Farmer leaders insist the violence was not planned. It was an outburst of anger and frustration, as their peaceful protest had failed to make the state government see reason.

Mahapanchayat Venue Turned into Police Camp

The Mahapanchayat on December 17 was called in the shadow of this violence. Even after state repression, the farmers have continued their protest and have vowed that the ethanol factory will not be allowed to operate until fresh environmental clearances are obtained and the consent of local residents is ensured.

The district administration imposed Section 163, banned gatherings and slogans, prohibited carrying sticks and travel by tractors, and suspended internet services. Over 1,400 police personnel were deployed, turning the entire area around the grain market in Hanumangarh Junction into a fortified police camp.

Despite this, thousands of farmers arrived from across many districts of Rajasthan and even neighbouring states. Leaders of the Samyukt Kisan Morcha—Rakesh Tikait, Gurnam Singh Chaduni and Jogendra Singh Ugrahan—addressed the Mahapanchayat, linking the Hanumangarh struggle to a broader national pattern of land and livelihood dispossession by the state-corporate nexus. Farmer leaders clearly stated that the agitation will continue until the MoU for the ethanol factory is cancelled.

Farmers Issue 20-day Ultimatum

The farmer leaders accepted the administration’s offer to hold talks. Discussions were held between farmer leaders and the administration oficials regarding the proposed construction of the ethanol factory in Rathi Kheda. Farmer leaders strongly presented their key demands during the talks. Their demands were clear: cancel the MoU signed with the ethanol company and withdraw all cases filed against protesting farmers.

Officials assured them that the demands would be forwarded to higher authorities. However, no concrete decision was announced by the administration. In response, farmers issued a 20-day ultimatum to the administration to fulfil their demands.

The Mahapanchayat concluded peacefully, with farmers issuing a clear warning that if their demands are not met within the stipulated time frame, they will again resort to a large agitation and call another Mahapanchayat in Sangaria on January 7. Farmer leaders clarified that the agitation will continue peacefully for the next 20 days.

Meanwhile, the state government had announced the formation of a five-member committee to examine the potential impacts of the ethanol factory on groundwater levels and the environment. This committee will provide a detailed assessment report, based on which further action and decisions will be taken. Farmers, today, rejected the committee outright, pointing out that it consists entirely of government bureaucrats.

Beyond Hanumangarh

The Samyukt Kisan Morcha has condemned the police crackdown and extended full support to the agitation. It has demanded the release of arrested farmers, compensation for the injured, and discussions with the Sangharsh Samiti to resolve all the pressing demands of the protesting farmers. SKM has accused the Union and state governments of promoting corporate interests by attacking farmers and usurping fertile farmland.

As the standoff enters a critical phase, for the farmers of Tibbi, the struggle is no longer only against an ethanol plant. It is about who decides the future of land and water—and whether rural livelihoods and ecology can survive the march of an ecologically destructive, corporatised model of industrial “development.”

________________

All images courtesy Shailendra, an activist from Rajasthan.

Also Read: Ethanol Giant in Rajasthan Face Fierce Peasant Resistance Despite Police Brutality