What’s at stake in Chandigarh is the future of India’s federal democracy. The move to alter the status of Chandigarh fits more into the larger pattern of the RSS-BJP’s agenda of systematic centralisation of power by weakening of federal structures.

Groundxero | Nov 23, 2025

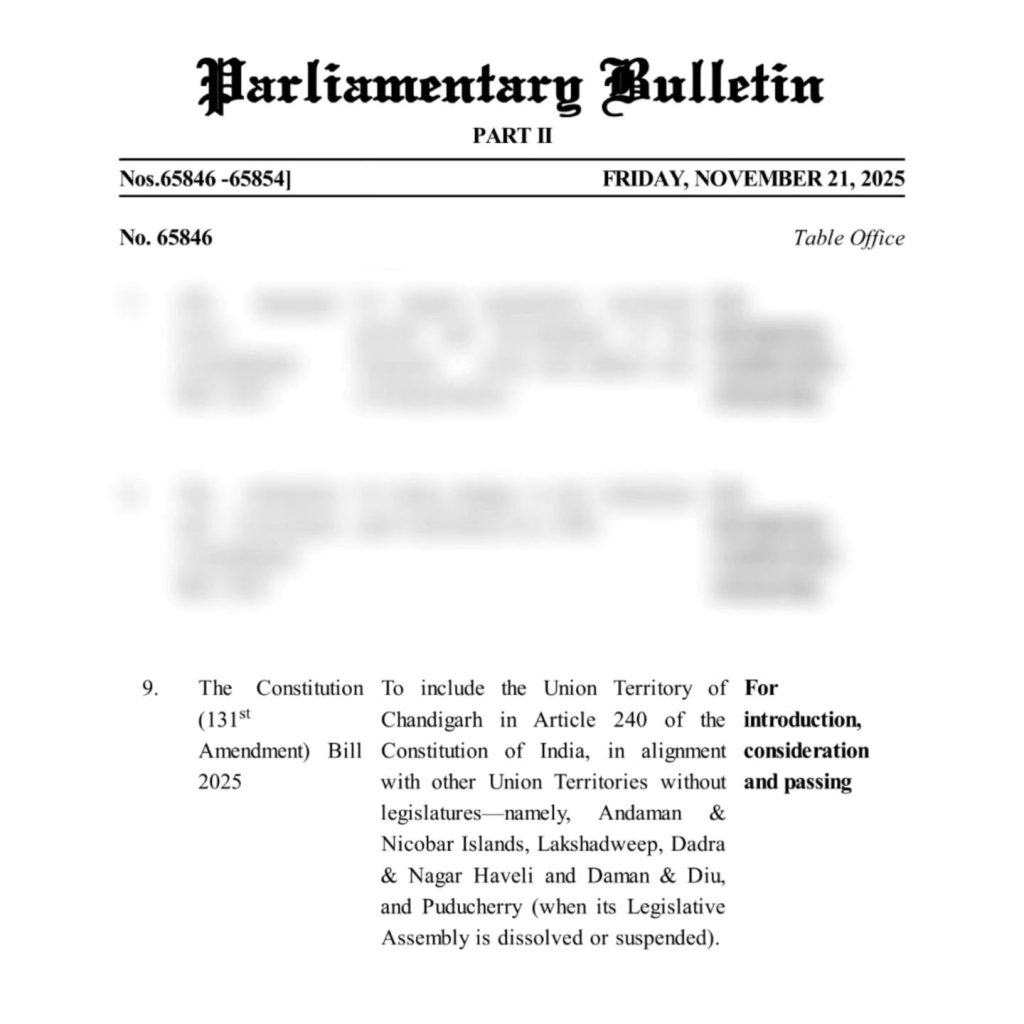

The Union Home Ministry’s announcement on 23 November that it will not introduce the proposed Constitution (131st Amendment) Bill, 2025 to alter the status of Chandigarh in the upcoming Winter Session has temporarily diffused a political crisis. The Home Ministry’s issued a clarification that “no final decision has been taken” to bring Chandigarh under Article 240. But that the issue “is still under consideration at the level of Central Government”—means the move is paused, not abandoned.

The proposed Bill seeks to include the Union territory of Chandigarh under the ambit of Article 240, in alignment with other UTs without legislatures such as Andaman & Nicobar Islands, Lakshadweep, Dadra & Nagar Haveli and Daman & Diu, and Puducherry. The Bill aimed to hand over Chandigarh’s administration to a Delhi via the Union government appointed Lieutenant Governor. Article 240 of the Constitution empowers the President to make regulations for the UT and legislate directly, bypassing the state government.

The move sparked fierce political reaction across Punjab, with all major political parties, including Aam Aadmi Party, Akali Dal and Congress opposing it and accusing Centre of trying to “weaken” Punjab’s historic and emotional claim over Chandigarh.

Chandigarh was built as a planned city to be post-partition Panjab’s capital after Lahore went to Pakistan. After the Punjab’s reorganisation in 1966, and its trifurcation, Chandigarh was made the joint capital of Punjab and Haryana. It was administered independently by the chief secretary. However, since 1984, Chandigarh has been administered by Punjab governor.

The transfer of Chandigarh to Punjab has been a long-standing demand and aspiration of the people of the Punjab. The issue formed a core component of the injustices that the Punjab movement raised. The Union government had accepted in principle to transfer Chandigarh to Punjab in 1970. Its resolution was once agreed upon in the Rajiv–Longowal Accord, and a deadline of January, 1986 was fixed for the transfer of Chandigarh to Punjab. The accord was also ratified by Parliament.

Yet, nearly four decades later, these promises still remain unfulfilled. Delhi has repeatedly reneged on its commitments, deliberately keeping the issue unresolved for decades. Successive governments at the centre have steadily diluted Punjab’s claim to Chandigarh —most notably in 2016, when the Modi government attempted to appoint former IAS officer K.J. Alphons as an independent administrator of Chandigarh. However, the move was withdrawn after an uproar within Punjab and stiff opposition from the then Punjab chief minister, Parkash Singh Badal, from Akali Dal, which part of the BJP-led NDA ruling alliance at the centre.

The proposal of Amendment is a direct provocation and a yet another assault on Punjab rights—whether on Chandigarh, river waters or Punjab University. In Punjab, the move was seen not as an administrative measure but as a continuation of the historic injustices committed against the people of the state. The attempted legislation has a clear motive — negate Punjab’s historical and emotional claim over its own capital.

Punjab Chief Minister Bhagwant Mann said it is a grave injustice that the BJP government is “conspiring to snatch” Punjab’s capital. Punjab Congress president Amarinder Singh Raja said “Chandigarh belongs to Punjab and any attempt to snatch it away will have serious repercussions.”

Describing the proposed legislation as an “assault on the rights of Punjab” Shiromani Akali Dal (SAD) president Sukhbir Singh Badal Badal said the Bill was not only against federalism, it would be a “betrayal” of the commitments given by the Centre to restore Chandigarh to Punjab.

Even Punjab BJP chief Sunil Jakhar, sensing the public mood to the Centre’s proposal, asserted that Chandigarh “is an integral part of Punjab.” Posting on X, he said the Punjab BJP “stands firmly with the interests of the state, whether it is the issue of Chandigarh or the waters of Punjab.”

Seen in isolation, the Amendment may appear technical, as the Home Ministry emphasized in its clarification that the Bill only seek to “simplifying the process of law-making for the Union Territory by the Central Government” But placed alongside the Modi government’s abrogation of Article 370 in Jammu & Kashmir, its bifurcation into UTs to the enactment of the CAA–NRC, from repeated assaults on democratic institutions to the authoritarian push of the three anti-peasant Farm Laws, the Chandigarh proposal looks less like an administrative reform. It fits more into the larger pattern of the RSS-BJP’s agenda of systematic centralisation of power to establish its ideological and political hegemony by weakening of federal structures.

This government has consistently trampled upon people’s livelihood, states’ rights, regional aspirations, and the constitutional framework itself. The people of Punjab have offered one of the most resolute and inspiring resistance to these authoritarian attacks. Whether in opposing the CAA–NRC, defending the autonomy of Punjab University’s senate, or leading the historic farmers’ movement, Punjab has repeatedly forced the Modi government to retreat.

During the past several weeks, Punjab University in Chandigarh has become the site of one of the most significant student-led democratic struggles in recent years. On 28 October, 2025, the central government issued a notification drastically restructuring the Punjab University Senate—downsizing it from 97 to 31 members and eliminating most elected seats, including the graduate constituency. In response, students, teachers, alumni, farmers and workers unions, and civil society groups across Punjab erupted in massive protests under the banner of the Punjab University Bachao Morcha.

What began as a protest to defend the Senate quickly developed into a wider battle over university autonomy, federal rights, and democratic governance. The students’ movement—drawing support from farmers’ unions, trade unions, social and political organisations across Punjab—forced the central government to withdraw the notification.

But the agitation continues as students demand immediate restoration of Senate elections, dismissal of criminal cases against protesting students, and a moratorium on major administrative decisions until an elected Senate is constituted.

Punjab is one of the few states where sustained, broad-based resistance continues to challenge Modi’s authoritarian governance. While the Union government might have backtracked at present, but the PIB statement on X, stating that the proposal is still under consideration means it is not a retreat, it is just a postponement of the decision. Once the political climate is more favourable—the government could revive the Amendment.

Punjab’s political parties understand this. Its people understand it. Delhi’s long history of reneging on commitments has made them conscious that the issue of Chandigarh is not merely an administrative dispute but a political fight for Punjab in its larger struggle to protect its political and cultural identity.

One of the major signs of an authoritarian or fascists regime is concentration of power at the centre in the hand of the supreme leader. The assault on Punjab and on the federal rights of other opposition party ruled state are not mere administrative measure but are part of the right wing RSS-BJP’s agenda to impose its ideological and political hegemony on these states and societies.

At its core, the issue is about the nature of Indian federalism. Should the rulers in Delhi be able to override regional aspirations through executive fiat? Can a Union government through brute majority convert state territories into UTs governed by appointed administrators without meaningful consultation with the concerned states?

These questions do not concern Punjab alone. They concern every state that found itself at odds with the Centre—from Tamil Nadu to Kerala, Telangana to West Bengal. All progressive and democratic forces—not only across Punjab, but throughout the country—must launch a united broader struggle against every authoritarian move of the centre to defend federalism, democracy, and constitutional justice in India today.