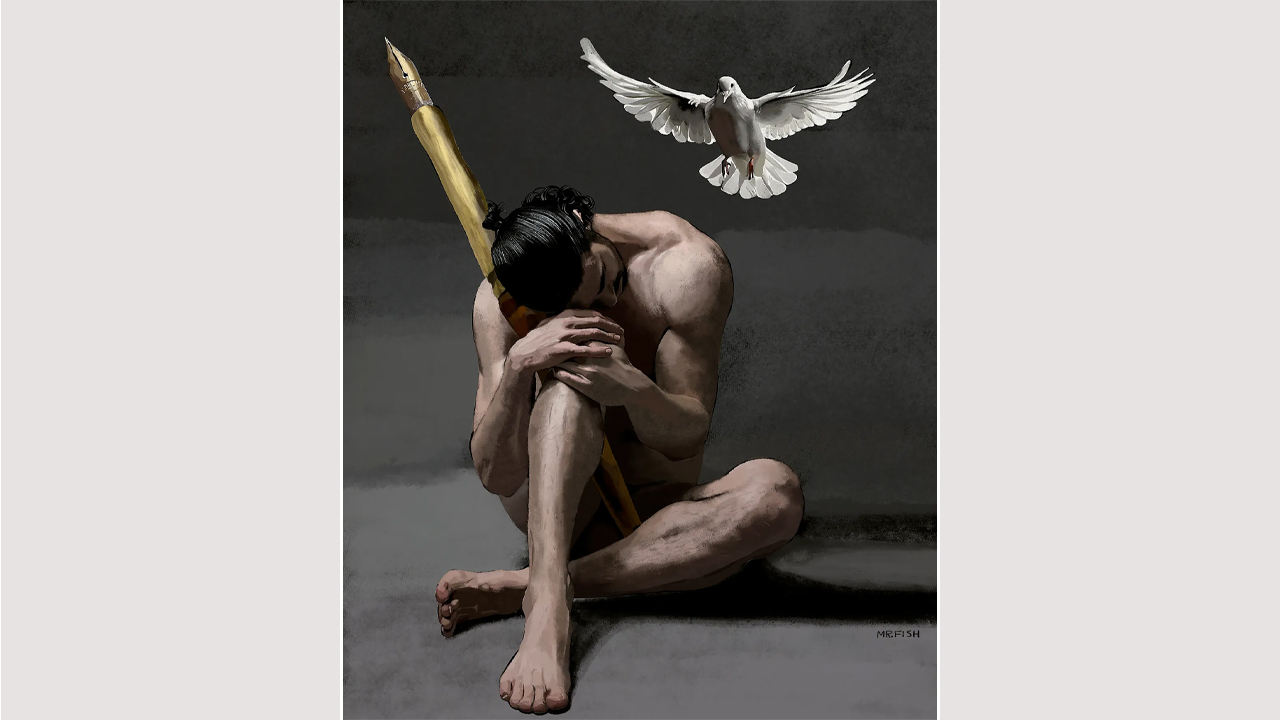

A year ago on Dec. 6, 2023 Israel murdered Palestinian poet Refaat Alareer in Gaza. His poems, however, remain, condemning his killers and beseeching us to honor our shared humanity.

By CHRIS HEDGES

DEC 11, 2024

Dear Refaat,

We are not silent. We are being silenced. The students who, during the last academic year set up encampments, occupied halls, went on hunger strikes and spoke out against the genocide, were met this fall with a series of rules that have turned university campuses into academic gulags. Among the minority of academics who dared to speak out, many have been sanctioned or dismissed. Medical professionals who criticize the wholesale destruction by Israel of hospitals, clinics and targeted assassinations of health workers in Gaza have been suspended or terminated from medical school faculties with some facing threats to revoke their medical licenses.

Journalists who detail the mass slaughter and expose Israeli propaganda have been taken off air or fired from their publications. Jobs are lost over social media posts. The tiny handful of politicians who condemn the killing have seen millions of dollars spent to drive them from office. Algorithms, shadow-banning, deplatforming and demonetizing – all of which I have experienced – are used to marginalize or ban us on digital media platforms. A whisper of protest and we are disappeared.

None of these measures will be lifted once the genocide ends. The genocide is the pretext. The result will be one huge step towards an authoritarian state, especially with the ascendancy of Donald Trump. The silence will expand, like a great cloud of sulfurous gas. We choke on forbidden words. They killed you. They are strangling us. The goal is the same. Erasure. Your story, the story of all Palestinians, is not to be told.

The Zionists and their allies have nothing left in their arsenal but lies, censorship, smear campaigns and violence, the blunt instruments of the damned. But I hold in my hand the weapon that will, ultimately, defeat them. Your book, “If I must Die: Poetry and Prose”.

“Stories teach life,” you write, “even if the hero suffers or dies in the end.”

Writing, you told your students, “is a testimony, a memory that outlives any human experience, and an obligation to communicate with ourselves and the world. We lived for a reason, to tell the tales of loss, survival, and of hope.”

It has been a year since an Israeli missile targeted the second-floor apartment where you were sheltering. You had been receiving death threats for weeks online and by phone from Israeli accounts. You had already been displaced multiple times. You fled in the end to your sister’s home in Al-Sidra neighborhood in Gaza City. But you did not escape your hunters. You were murdered with your brother Salah and one of his children and your sister and three of her children.

You wrote your poem “If I Must Die” in 2011. You released it again a month before your death. It has been translated into dozens of languages. You wrote it for your daughter Shymaa. In April 2023, four months after your death, Shymaa was killed in an Israeli airstrike along with her husband and their two-month-old son, your grandson, who you never met. They had sought refuge in the building of the international relief charity Global Communities.

Your write to Shymaa:

If I must die,

you must live

to tell my story

to sell my things

to buy a piece of cloth

and some strings,

(make it white with a long tail)

so that a child, somewhere in Gaza

while looking heaven in the eye

awaiting his dad who left in a blaze—

and bid no one farewell

not even to his flesh

not even to himself—

sees the kite, my kite you made, flying up above

and thinks for a moment an angel is there

bringing back love

If I must die

let it bring hope

let it be a tale

You have joined the martyred poets. The Spanish poet Federico García Lorca. The Russian poet Osip Mandelstam. The Hungarian poet Miklós Radnóti who wrote his final verses on a death march. The Chilean singer and poet Víctor Jara. The Black poet Henry Dumas, shot dead by New York City police.

In your poem “And We Live On…” you write:

Despite Israel’s birds of death

Hovering only two meters from our breath

From our dreams and prayers

Blocking their ways to God.

Despite that.

We dream and pray,

Clinging to life even harder

Every time a dear one’s life

Is Forcibly rooted up.

We live.

We live.

We do.

Why do killers fear poets? You were not a combatant. You did not carry a weapon. You put words on paper. But all the might of the Israeli army and intelligence services were deployed to track you down.

In times of distress, when the world is enveloped by cruelty and suffering, when lives are perched on the edge of the abyss, poetry is the sad lament of the oppressed. It makes us feel the suffering. It is intuitive. It captures the mix of complex emotions — joy, love, loss, fear, death, trauma, grief — when the world falls apart. It creates in its beauty a salvific meaning out of despair. It is an absurd act of hope, a defiant act of resistance, taunting those who dehumanize you with erudition and sensitivity. Its fragility and beauty, its sanctification of memory, experience and the intellect, its musicality, mock the simplistic slogans and cant of the killers.

In your poem “Freshly Baked Souls” you write:

The hearts are not hearts.

The eyes can’t see

There are no eyes there

The bellies craving for more

A house destroyed except for the door

The family, all of them, gone

Save for a photo album

That has to be buried with them

No one was left to cherish the memories

No one.

Except freshly baked souls in bellies.

Except for a poem.

Writing, as Edward Said reminds us, is “the final resistance we have against the inhuman practices and injustices that disfigure human history.”

Violence cannot create. It only destroys. It leaves nothing of value behind.

“Don’t forget that Palestine was first and foremost occupied in Zionist literature and Zionist poetry,” you said in a lecture given to your students in Advanced English Poetry at the Islamic University in Gaza. “When the Zionists thought of going back to Palestine, it wasn’t like, ‘Oh, let’s go to Palestine.’”

You snapped your fingers:

It took them years, like over fifty years of thinking, of planning, all the politics, money, and everything else. But literature played one of the most crucial roles here. This is our class. If I tell you, ‘let’s move to the other class.’ you need guarantees that we’re going to go there, we’re going to find chairs — right? That the other class, the other place, is better, is more peaceful. That we have some kind of connection, some kind of right.

So, for fifty years before the occupation of Palestine and the establishment of the so-called Israel in 1948, Palestine in Zionist Jewish literature was presented to the Jewish people around the world [as]… ‘a land without a people [for] a people without a land.’ ‘Palestine flows with milk and honey.’ ‘There is no one there, so let’s go.’

Killers are trapped in a literal world. Their imaginations are calcified. They have shut down empathy. They know poetry’s power, but they do not know where that power comes from, like an audience left gaping at the deft skill of a magician. And what they cannot understand they destroy. They lack the capacity to dream. Dreams terrify them.

The Israeli general Moshe Dayan said that the poems of Fadwa Tuqan, who was educated at Oxford, “were like facing twenty enemy fighters.”

Taqan writes in “Martyrs Of The Intifada” of the youth throwing stones at heavily armed Israeli soldiers:

They died standing, blazing on the road

Shining like stars, their lips pressed to the lips of life

They stood up in the face of death

Then disappeared like the sun.

Many Palestinians can recite from memory passages of the poems “To My Mother” and “Write Down I am an Arab” by Palestine’s most celebrated poet Mahmoud Darwish. Israeli authorities persecuted, censored, imprisoned and kept Darwish under house arrest before driving him into exile. His lines adorn the concrete barriers erected by Israel to wall off the Palestinians in the West Bank and are incorporated into popular protest songs.

His poem “Write Down I am an Arab” reads:

Write down:

—I am an Arab

And my ID number is 50,000

I got eight kids

And the ninth is due after summer.

So will you be mad?

—I am an Arab

And I work along with my labor buddies in a stone quarry

And I got eight kids

I secure them bread, clothing and notebooks

Hacked out of the rocks

And I don’t beg for charity at your door,

And don’t lower myself at the footsteps of your court

—So will you be mad?

Write down:

—I am an Arab.

I am a name without an epithet,

Patient in a country where everything

has a tantrum.

—My roots

—Were deeply entrenched before the birth of time

—And prior to the ushering of eras,

—Before cypresses and olive trees,

—And even before the grass grew.

My dad hails from a family of plowers, not blue-blood barons

My grandpa was a farmer, totally unknown

Taught me about the zenith of the soul before teaching me how to read

And my home is a cabin made out of sticks and bamboos

So are you displeased with my status?

I am a name without an epithet!

Write down:

—I am an Arab.

Hair color: coal-like; eye color: brown

Distinguishing marks: I wear a headband on top of a keffiyeh

—And my palm is rock-solid, scratches whoever touches it

As to my address: I am from an isolated village, forgotten

—Its streets are unnamed

—And all its men are in the field or in the stone quarry

—So will you be mad?

Write down.

—I am an Arab

You stole the meadows of my ancestors and a land I used to cultivate

—Together with all my kids

—You didn’t leave to us or to my offspring

—Anything – except these rocks

—So will your government take them away as well, as it’s been announced

—In that case

—Write down

—On the top of the first page:

—I don’t hate people and I don’t rob anyone

—But… If I starve to death, I’m left with nothing else but

—The flesh of my usurper to feed from

—So beware, beware of my hunger and anger

You wrote about your children. Your words were to be their legacy.

To your daughter Linah, then eight-years-old, or as you say “in Gazan time, two wars old,” you told bedtime stories when Israel was bombarding Gaza in May 2021, when your children “all sat up in bed, shaking, saying nothing.” You did not leave your home, a decision you made so “we would die together.”

You write:

On Tuesday, Linah asked her question again after my wife and I didn’t answer it the first time: Can they destroy our building if the power is out? I wanted to say: “Yes, little Linah, Israel can still destroy the beautiful al-Jawharah building, or any of our buildings, even in the darkness. Each of our homes is full of tales and stories that must be told. Our homes annoy the Israeli war machine, mock it, haunt it, even in the darkness. It can’t abide their existence. And, with American tax dollars and international immunity, Israel presumably will go on destroying our buildings until there is nothing left.”

But I can’t tell Linah any of this. So I lie: “No, sweetie, they can’t see us in the dark.”

Mass death was not new to you. You were shot by Israeli soldiers with three rubber-coated metal bullets when you were a teenager. In 2014, your brother, Hamada, your wife’s grandfather, her brother, her sister and her sister’s three children were all killed in an Israeli strike. During the bombardment Israeli missiles destroyed the offices of the English Department at the Islamic University of Gaza, where you stored “stories, assignments, and exam papers for potential book projects.”

The Israeli army spokesman claimed they bombed the university to destroy a “weapons development center,” a statement later amended by the Israeli defense minister who said “IUG was developing chemicals, to be used against us.”

You write:

My talks about tolerance and understanding, Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions (BDS) and nonviolent resistance, and poetry and stories and literature did not help us or protect us against death and destruction. My motto “This too shall pass” became a joke to many. My mantra “A poem is mightier than a gun” was mocked. With my own office gone by wanton Israeli destruction, students would not stop joking about me developing PMDs, “Poems of Mass Destruction,” or TMDs, “Theories of Mass Destruction.” Students joked that they wanted to be taught chemical poetry alongside allegorical and narrative poetry. They asked for short-range stories and long-range stories instead of normal terms like short stories and novels. And I was asked if my exams would have questions capable of carrying chemical warheads!

But why would Israel bomb a university? Some say Israel attacked IUG just to punish its twenty thousand students or to push Palestinians to despair. While that is true, to me IUG’s only danger to the Israeli occupation and its apartheid regime is that it is the most important place in Gaza to develop student’s minds as indestructible weapons. Knowledge is Israel’s worst enemy. Awareness is Israel’s most hated and feared foe. That’s why Israel bombs a university: it wants to kill openness and determination to refuse living under injustice and racism. But again, why does Israel bomb a school? Or a hospital? Or a mosque? Or a twenty-story building? Could it be, as Shylock put it, “a merry sport”?

The existential struggle of the Palestinians is to reject the barbarity of the Israeli occupiers, to refuse to mirror their hatred or replicate their savagery. This does not always succeed. Rage, humiliation and despair are potent forces that feed a lust for vengeance. But you heroically fought this battle for your humanity, and ours, until the end. You embodied a decency your oppressors lacked. You found salvation and hope in the words that captured the reality of a people facing erasure and death. You asked us to feel for these lives, including your own, which have been lost. You knew that there would come a day, a day you understood you might never see, when your words would expose the crimes of those who murdered you and lift up the lost lives of those you honored and loved. You succeeded. Death took you. But not your voice or the voices of those you memorialized.

You, and they, live on.

Chris Hedges is a Pulitzer Prize–winning author and journalist who was a foreign correspondent for 15 years for The New York Times.

The Chris Hedges Report is a reader-supported publication.

Read the original article.