“Thanksgiving’ is a white-washed holiday designed to conceal its true origins of violence, genocide, land theft, and forced assimilation,” said the Indigenous Environmental Network.

Nov 28, 2024

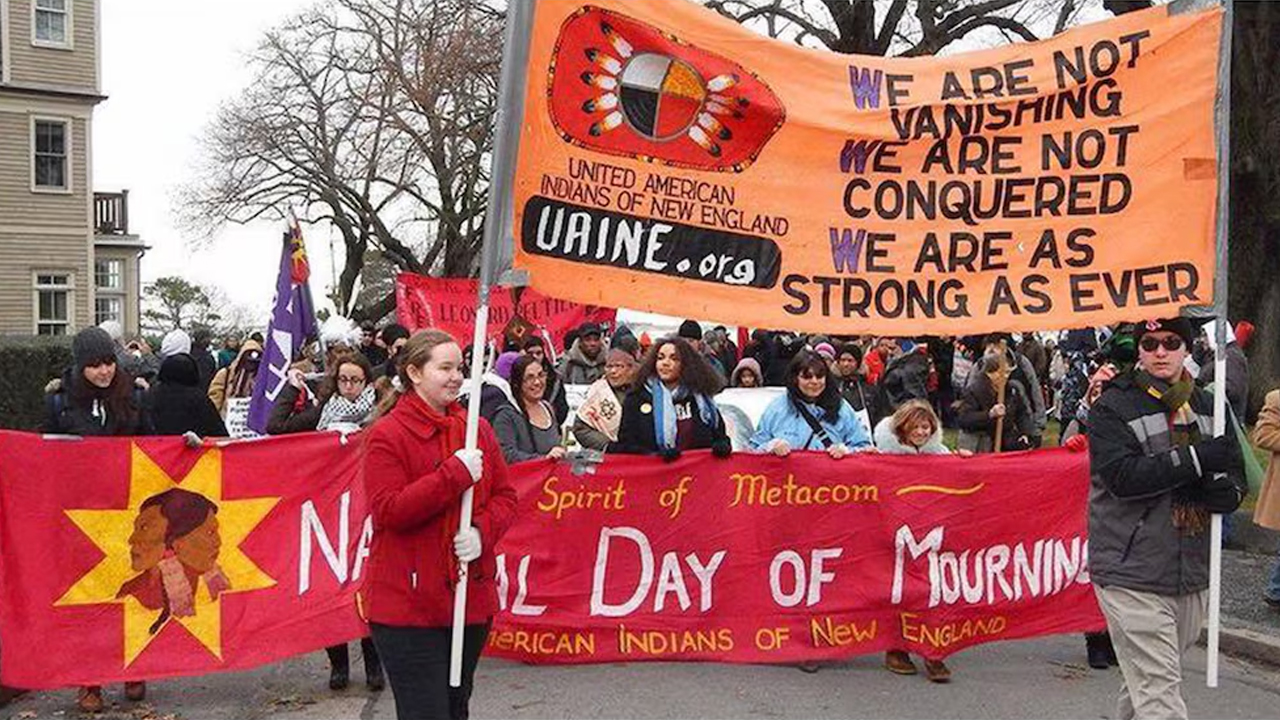

In contrast with Thanksgiving celebrations across the United States on Thursday, Native Americans held a National Day of Mourning, promoted accurate history, and championed Indigenous voices and struggles.

Despite rainy conditions, the United American Indians of New England held its 55th annual National Day of Mourning at Cole’s Hill in Plymouth, Massachusetts. Kisha James, who is an enrolled member of the Wampanoag Tribe of Gay Head (Aquinnah) and also Oglala Lakota, shared how her grandfather founded the event in 1970 and pledged to continue to “tear down the Thanksgiving mythology.”

“The past influences the present” and “the settler project” continues with racism, misogyny, and anti-LGBTQ+ discrimination, James told the crowd. “The Pilgrims are not ancient history.”

James took aim at fossil fuel pipelines, oil rigs, skyscrapers, corporations, the U.S. military, mass incarceration, and the criminalization of immigrants, and declared that “no one is illegal on stolen on land.”

Jean-Luc Pierite, a member of the Tunica-Biloxi Tribe of Louisiana and president of the board of directors of the North American Indian Center of Boston who helped organize this year’s gathering, told USA Today that “while we are mourning some tragic history but also contemporary issues, we are also expressing gratitude for each [other] and building this community space.”

“Coming together as a community for a feast and to express gratitude—that’s not something that was imported to this continent because of colonization,” Pierite said. “Indigenous peoples have had these practices going back beyond, beyond colonial contact.”

This year’s event in Plymouth included speeches about the suffering of Palestinians—as Israel wages a U.S. government-backed war on the Gaza Strip that has killed at least 44,330 people, injured 104,933, and led to a genocide case at the International Court of Justice—and of people impacted by extractive industries.

“The message from Indigenous peoples internationally has been consistent: that we need to center the development of traditional ecological knowledge, Indigenous knowledge, and move away from fossil fuel extractive economies,” said Pierite. “At this time the world needs Indigenous peoples.”

On this day, Indigenous people and allies confront the settler-colonial narratives of “Thanksgiving,” observing it instead as a National Day of Mourning. The whitewashed story of unity with the Wampanoag people—who have long lived in southeastern Massachusetts and eastern Rhode… pic.twitter.com/3yRoyfohPj

— Jewish Voice for Peace (@jvplive) November 28, 2024

In New York City, police arrested 21 pro-Palestinian protesters who blocked the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade route.

According to ABC 7:

For the second year in a row, the group ran in front of the Ronald McDonald float to briefly stop the parade.

This year, they jumped the barricades at West 55th Street just after 9:30 am.

Many sat on the ground, locking arms and chanting “Free, free Palestine!“

Others held a banner behind them, reading “Don’t celebrate genocide! Arms embargo now.”

Video footage shared on social media shows members of the New York Police Department grabbing protesters and their banner, and throwing at least one person face-first into the road.

BREAKING: Autonomous anti-genocide activists bring the Macy’s Thanksgiving Day Parade to a grinding halt after blockading the McDonald’s float for a second year in a row. pic.twitter.com/Aj6XRsUF9T

— Talia Jane ❤️? (@taliaotg) November 28, 2024

Multiple Indigenous groups circulated messages about Thanksgiving on social media Thursday.

NDN Collective said that “as Indigenous peoples, we reject colonial holidays rooted in the genocidal erasure of our existence. We demand #LANDBACK to reclaim sovereignty, repair ties with Mother Earth, and protect Indigenous ways of life—honoring them for generations to come.”

The Indigenous Environmental Network similarly highlighted that “‘Thanksgiving’ is a white-washed holiday designed to conceal its true origins of violence, genocide, land theft, and forced assimilation.”

“We must re-evaluate what we’ve been taught about the history of this land and recognize that genocide, extraction, and exploitation of our lands and communities continue today,” the group argued.

Decolonize Thanksgiving by honoring Indigenous peoples. Here are ways how. pic.twitter.com/d5cgP332HV

— ACLU of Florida (@ACLUFL) November 28, 2024

Brenda Beyal, an enrolled member of the Diné Nation and program coordinator of the Brigham Young University ARTS Partnership’s Native American Curriculum Initiative, wrote about the history of Thanksgiving on Wednesday for The Salt Lake Tribune.

“Our history books mark ‘the first Thanksgiving’ in 1621 when at least 90 Wampanoag men, led by Massasoit, walked in on a Puritan harvest feast,” Beyal detailed. “Approximately 150 years later, all 13 colonies celebrated a day of solemn Thanksgiving to celebrate the win of the Battle of Saratoga in December of 1777. [U.S. President] George Washington called for a day of thanksgiving and prayer in 1789 to give gratitude for the end of the Revolutionary War.”

“Then, in 1863, [President] Abraham Lincoln proclaimed Thanksgiving a national holiday to be held in November of every year,” she continued. “During the same year that Lincoln canonized Thanksgiving, the Shoshone experienced the worst slaughter of Native Americans in U.S. history while winter camped on the Boa Ogoi (Bear River) near what is now Preston, Idaho. More than 400 men, women and children were massacred.”

“This Thursday, my family and I will gather for a meal of thanksgiving. I have extended an invitation to whomever needs a place to rest, feast, and give gratitude. There is room at my table,” she explained. “Ultimately, it is my hope that we as a nation can continue to consecrate days of remembrance, where we can both celebrate and mourn, acknowledge and repair, and find ways to be thankful, even with a wounded heart.”

Many Native Americans observe Thanksgiving, a few don’t, but the main thing to remember is no matter where anyone is today, they are on lands that were ripped off from Indigenous nations, an injustice still ongoing to this day because Native people are still here! pic.twitter.com/68LVg76Nbw

— Brett Chapman (@brettachapman) November 28, 2024

Writing for the San Francisco Chronicle on Thursday, Diné/Dakota writer Jacqueline Keeler addressed the future under U.S. President-elect Donald Trump, who won another term in the White House this month.

“In my book Standoff: Standing Rock, the Bundy Movement, and the American Story of Sacred Lands, which was published after Trump’s first term, I delved into the settler colonial mindset that the Pilgrims landed with on these shores, and contrasted it with the perspective of the Indigenous people of the United States,” Keeler noted.

“Origin stories define people by articulating the terms of their relationships with our Mother, the Earth, as well as other living beings, and each other. In my book, I proposed that these stories could act as algorithms,” she continued. “The ‘origin story’ algorithm for settler colonists was straightforward; they came to other people’s lands, occupied them, and sent the wealth back to their ruling 1%. Based on that origin story, you can predict what Trump and his base will do next.”

“My question at Thanksgiving time,” she concluded, is “how do we create a new origin story that includes everyone and puts us on a path to come together as a people—in harmony with each other and the Earth, our Mother.”

Lakota historian Nick Estes, a citizen of the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe and co-founder of the Indigenous group the Red Nation, appeared on Democracy Now! on Thursday to discuss the origins of Thanksgiving and his book Our History Is the Future, which focuses on seven historical moments of resistance that form a road map for collective liberation.

Estes examined the Standing Rock Sioux Tribe’s battle against the climate-wrecking Dakota Access Pipeline. “I actually look at a physical map that was handed out to water protectors who came to the camp. And on that map there was, you know, where to find food, where to find the clinics,” he said. “To me, that provided, you know, a kind of interesting parallel to the world that surrounded the camps.”

“You had the North Dakota National Guard, the world of cops, the world of the militarized sort of police state. And in the camps themselves you had sort of the primordial sort of beginnings of what a world premised on Indigenous justice might look like. And in that world, you know, everyone got free food. There was a place for everyone,” Estes noted. “The housing… obviously, was transient housing and teepees and things like that, but then also there was health clinics to provide healthcare, alternative forms of healthcare, to everyone. And so, if we look at that, it’s housing, education—all for free, right?—a strong sense of community.”

“Given the opportunity to create a new world in that camp, centered on Indigenous justice and treaty rights, society organized itself according to need and not to profit. And so, where there was, you know, the world of settlers, settler colonialism, that surrounded us, there was the world of Indigenous justice that existed for a brief moment in time,” he said. “And in that world, instead of doing to settler society what they did to us—genociding, removing, excluding—there’s a capaciousness to Indigenous resistance movements that welcomes in non-Indigenous peoples into our struggle, because that’s our primary strength, is one of relationality, one of making kin.”

Jessica Corbett is a senior editor and staff writer for Common Dreams.

This article is republished from Common Dreams under a Creative Commons license.

Read the original article.