Labour activists, journalists, writers and lawyers, under a group named ‘Delhi for Workers’, organised a solidarity meeting for the ongoing workers’ struggles across sectors in India at the Press Club of India, New Delhi, to highlight these significant struggles, and inviting members of the press and concerned citizens to know and write more about these struggles.

Groundxero | October 16, 2024

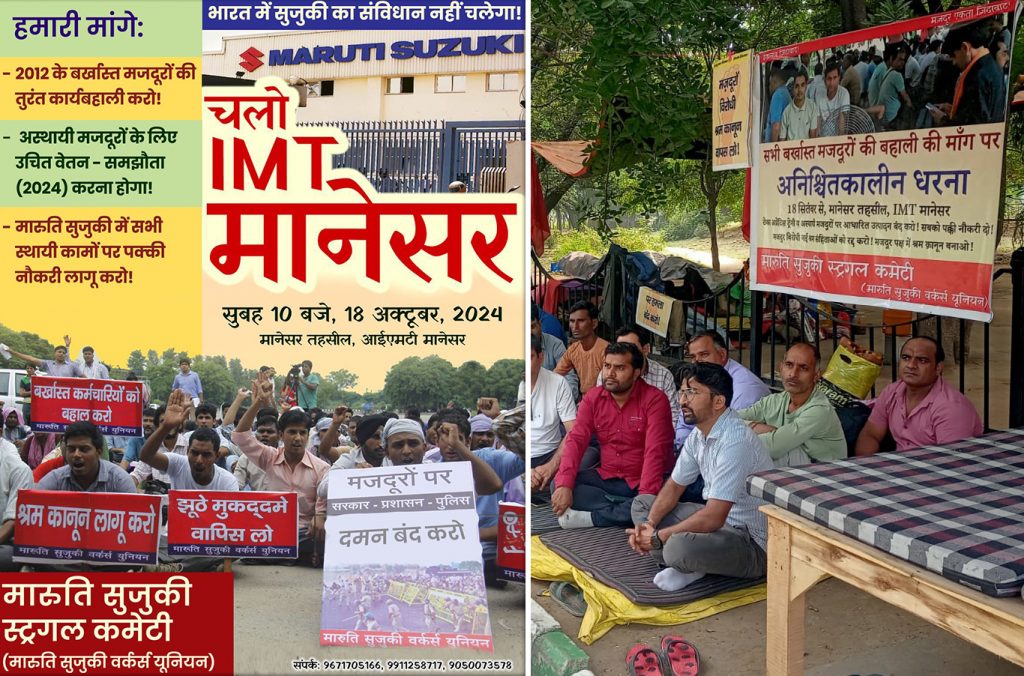

In the last few months, several protests, demonstrations and strikes across India have rekindled hope and interest about working class movements against the multipronged tyranny of Indian corporates and governments. The Samsung workers’ strike in Sriperumbudur industrial belt in Tamil Nadu, the tea garden workers’ movement in Darjeeling hills in West Bengal, the terminated Maruti Suzuki workers’ dharna in Manesar industrial belt in Haryana and the Dolphin-Lucas TVS workers’ strike and dharna in Udham Singh Nagar in Uttarakhand are some of the prominent ones among these. The mainstream media, primarily funded by the corporates, has as usual not played a promising role in conveying the details of these movements to the public and in some cases, have actively vilified the protesting workers.

On 16th October – ironically commemorated as the International Day for the Eradication of Poverty – a community of activists, journalists, writers and lawyers, under the title ‘Delhi for Workers’, organised a press meet cum solidarity meeting at the Press Club of India, New Delhi, to highlight these significant struggles, inviting members of the press and concerned citizens to know and write more about these.

Referring to the misleading or discriminatory roles the media houses have been playing, Delhi for Workers urged through its leaflet:

“The issues and perspective of labour, which constitute a core aspect of any society, has been significantly marginalised in mainstream coverage of events in contemporary society. […] We rely upon and request the diligent and conscious journalism and public writings of members of the press and citizenry, as such those present in today’s gathering, to help us amplify the voices of the workers.”

45 years back on 17th October, 1979, the Neelam Chowk massacre in Faridabad was committed by the Haryana police. The Delhi for Workers press meet was dedicated to the victims of that massacre, in which striking workers were mercilessly beaten up and many innocent civilians including children were either shot at or were beaten up by the police and went missing.

While the Neelam Chowk massacre was an extreme but not an uncommon example of how the Indian state and Corporate value the working class, the ongoing struggles reveal different means through which workers are being exploited. The speakers at the press meet were Colin Gonsalves – senior advocate at the Supreme Court, Anil Chamadia – journalist and publisher, Anjali Deshpande – author and journalist, Satish – representative of Maruti Suzuki Struggle Committee of terminated Maruti workers, Ajit – representative of Bellsonica Auto Component India Employees Union, Santosh – labour activist and journalist and Nayanjyoti – labour activist and researcher. They brought out different aspects of the workers’ struggles mentioned above.

Satish, a terminated Maruti Suzuki worker, spoke about the past atrocities such as severe physical assaults by police, imprisonment of 13 workers, unlawful termination and struggle for survival faced by the 546 unlawfully retrenched workers and their families. He also spoke about the ongoing dharna and relay hunger strike in Manesar – a desperate measure that the Maruti Suzuki Struggle Committee has been forced to take in the face of years of suffering. For the past couple of days, the participants in the dharna have been threatened by the Haryana police. Though the Indian judiciary found these workers innocent of the so-called crime for which they were terminated, even today the police is allegedly accusing them of being criminals, trouble-makers and anti-patriotic. These tags are never attached to the corporates – the exploiters of the workers. Satish concluded his talk with an appeal to those present to join their protest program at the dharna site on 18th October in Manesar.

Ajit from Bellsonica Auto Component India Employees Union, spoke about the dire condition of workers – many of them women – in Dolphin-Lucas TVS. These workers received less than minimum wage, did not get a legal overtime wage rate for work beyond eight hours and lacked most basic facilities in their workplace. As a punishment for protests, 4000 permanent workers in the company were shifted to contractual status and 48 were terminated even without any enquiry. Dolphin is an auto-component supply company for Maruti, and the management in its five factories matches the ruthlessness of the Maruti management in exploiting its workers. While the workers are in struggle for the last one year, and have been demanding to be reinstated as permanent workers with full back wages, the company has repeatedly harassed them using the police and bouncers, especially harassing and humiliating women workers. Workers and solidarity activists have even been charged under the Goondas Act. But the workers are determined to intensify their struggle for reinstatement of the illegally retrenched workers, recognition of their union and settlement of their charter of demands. A Mazdoor-Kisan Mahapanchayat in Udham Singh Nagar was held recently in this matter. Ajit ended his speech by mentioning the repression and de-registration faced by the Bellsonica union for attempting to include contract workers as union members.

Senior SC advocate Colin Gonsalves, who had closely worked with the renowned militant trade union leader Dutta Samant, and had been vocal and active against the new labour codes, spoke about the extreme corruption in the Indian legal system that works in tandem with the state and the corporates. He described how despite many pro-labour judgments, the system is forced to remain useless unless workers organise themselves and raise their voices, militantly if required. He expressed hope that the young leadership in the trade unions might come up with new strategies to battle against the increasingly violent, immoral and powerful opponents.

Anjali Deshpande writes about workers’ struggles. Last year she and Nandita Haksar wrote a book on the history of the Maruti workers’ struggle. Anjali spoke about the dearth of writing on workers’ lives in our literature. Expressing concerns about increasing automation and further deterioration of workers’ plight, she also spoke about the discrimination by social movements such as the neoliberal feminist movement that tends to undermine what freedom for all women across class means.

Nayanjyoti spoke about the struggle of nearly a lakh of workers in the tea gardens of Darjeeling demanding a 20 percent festival bonus. The tea garden workers are one of the poorest worker communities in India, thanks to the management’s adamant stand to not pay even the minimum wage and inadequate or no bonus at all. The garden delves into massive wage and provident fund theft, and does not provide even the most basic perks and facilities to the tea garden workers. While the tea garden workers are at present on a relay hunger strike in a few gardens, here too, political pressure and police oppression are gradually getting harsher. Nayanjyoti explained the political and economic significance of the movement primarily for the 20% bonus to be given at one go. He mentioned how women workers are playing the most significant role in bringing this movement to the forefront.

Anil Chamadia spoke about how big media houses are bought and owned by corporations. He too extensively spoke about the appropriation of social justice movements in order to hoodwink injustice towards workers. Mentioning the negative role of the mainstream media against movements such as the largest Bharat Bandh on April 2, 2018, against the SC/ST amendment Act and the farmers’ movement, he energetically spoke about his convictions that silence of mainstream media will not silence the workers’ struggle for their rights, their need to come together and act.

Santosh concluded by briefly discussing the Samsung workers’ movement, which underwent a settlement between the striking workers and the management on the same day as the program. The movement that began for recognition of a CITU-led union, better wage as well as better facilities such as food and transportation, remained unresolved as the management was opposed to recognise workers’ union. However, for over a month, over 1000 workers stopped working and sat in a protest dharna that brought to light facts such as low wage and precarious workplace conditions of the permanent workers in a major manufacturing company like Samsung.

Though these struggles are in different parts of the country, they are not so different. As the corporates are finding new strategies to make deeper divisions among workers by creating categories of contract workers, apprentices, trainees etc. on top of caste-religion-gender based divisions, they are also increasingly reluctant to allow unionisation of contract workers. On the other hand, in many companies, permanent workers’ unions are easier to appropriate by the management, especially when these are comparatively high-paid employees with more to lose. If a union seems a potential trouble for a company’s profit-oriented exploitations of the workers, then vilification and repression are the ways to restrain them. The corporate and the State are also wary about allowing workers’ demonstrations and protests in the industrial belts such as Sriperumbudur and IMT Manesar, as it can be an inspiration for workers in other companies.

To prevent workers – especially contract workers – from unionising, the state has been violating various Acts such as Trade Union Act, Industrial Dispute Act, ILO Conventions, Contract Labour (Regulation and Abolition) Act and so on. Ironically, though these companies are not questioned for violating labour laws, the workers protesting the violations peacefully like sitting in hunger strike are often accused of being law-breakers for lack of permission from the court to do so. It is, however, fine by the state if these workers just starve at their homes and do not protest.

It’s important to consolidate the energy of struggles going on in different parts of the country in this era of voiceless and jobless growth.