One of the sanitation workers, Deepu, who survived the tragedy at Mughalsarai, said that if the private hospital had wanted, at least Vinod’s life could have been saved but due to the presence of feces on his body, the doctor shooed him away from a distance.

Groundxero | May 15, 2024

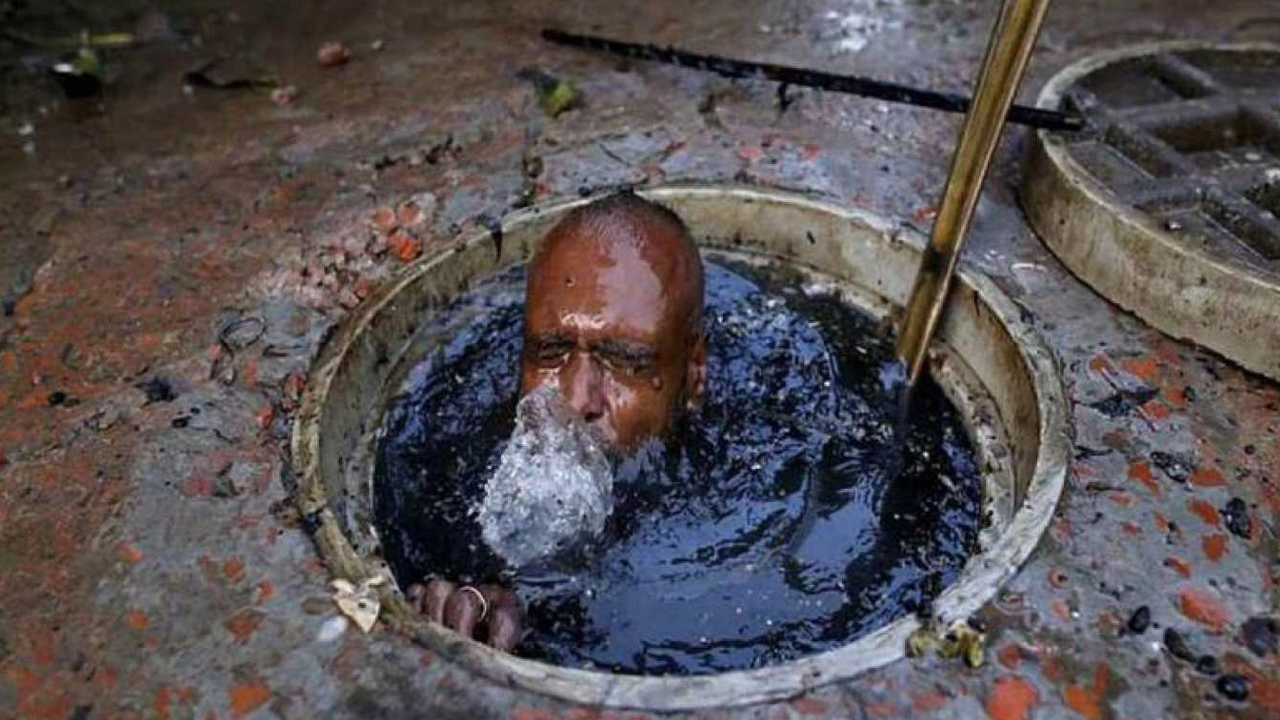

The death of sanitation workers while cleaning sewers and septic tanks without safety equipment and risking their lives continues. Recently, 8 workers engaged in cleaning of sewer lines and septic tanks died in Uttar Pradesh within a short span of ten days.

On 2nd May, Shroban Yadav, 57, and his son Sushil Yadav, 30, were killed while testing a sewer line in Lucknow’s Wazirganj area. On 3rd May, two daily wage-workers, Kokan Mandal, 40, and Nooni Mandal, 36, were killed while cleaning the septic tank of a private residence in Noida Sector 26.

Soon after on 9th May, four people including three sanitation workers died from inhaling toxic gases while cleaning the septic tank of a private house in Mughalsarai, Chandauli district of Uttar Pradesh. Three of the victims, Vinod Rawat, 35 Kundan, 42 and Loha, 23, were informal sanitation workers while the fourth victim was the son of the house owner who died while trying to save the workers. All of the deceased workers belonged to the Dom community of Kali Mahal colony of Mughalsarai. This is the second such incident in the Varanasi division within the last two months.

In another such incident on 12th May, a house-keeping staff member, Hare Krishan Prasad, was forced to enter the sewer in D Mall in Delhi, and died due to inhalation of toxic gases.

These deaths are testimony that manual scavenging is still prevalent in this country even after a decade of the practice being formally banned. Today, the deaths due to manual scavenging go unacknowledged by the government authorities who refuse to accept the crisis.

According to eyewitness’s account of the incident at Mughalsarai, when one of the three workers, Vinod Rawat, was taken out of the septic tank, he was still breathing. All the three workers were taken to a private hospital but were refused treatment and told to be taken to Banaras Trauma Center. An hour had passed by the time they reached the trauma centre and the three workers lost their lives due to delay in treatment.

One of the sanitation workers, Deepu, who didn’t go down into the septic tank and hence survived the tragedy at Mughalsarai, said that if the private hospital had wanted, at least Vinod’s life could have been saved but due to the presence of feces on his body, the doctor shooed him away from a distance. “People need us when they have to clean up the shit. After that people don’t even like to see us,” told Deepu.

The family members of the deceased sanitation workers alleged ‘we are made to work on contract basis and are paid only Rs 8-10 thousand per month. Contractors get the work done every day but do not pay our wages on time. To run the family, we are forced to work here and there, risking our lives.

The irresponsible and inhuman action of the private hospital probably cost the workers their lives. But no enquiry and action has reportedly been taken so far against the hospital. There has been no official talk of providing any compensation to these families yet. Their horrifying death did not make news headlines in any mainstream media.

A Press Conference was held on 15th May 2024 at the Press Club of India, New Delhi, where many advocates, journalists, and social activists expressed concern at the alarming number of deaths due to manual scavenging. Addressing the Press, Indira Unninayar, a senior advocate said that there is no proper data on the number of manual scavengers and the government hugely suppresses the number of manual scavenging deaths.

In all of the incidents, the workers worked as informal labourers or contractual sanitation workers and were made to clean sewer/septic tanks without any supervision. The sewer/septic tank workers are not provided with any safety equipment and often they have to face the toxic gases with just a handkerchief, said Radhika Bordia, a senior journalist who has been covering these cases for the last 25 years, at the press conference

Colin Gonsalves, senior advocate of the Supreme Court said that the municipal authorities should be held responsible for the deaths of these workers and held accountable for these offences which are as serious as murder charges. The local governance authorities have failed to fulfil the responsibility of supervising the cleaning in their jurisdiction and thus should be held liable for these deaths.

In October 2023 the Supreme Court ordered a compensation of 30 lakhs to the families of victims of manual scavenging which has not reached any of the victims so far. Allegedly, the District Administration promised to provide only ₹4 lakh ex gratia to each deceased in the incident in Chandauli. In India the lives of workers are considered cheap and inexpensive and they can only safeguard their rights through unionisation, said Roma, a senior activist from the All India Union of Forest Working People.

The Press Conference in Delhi was organised by Dalit Adivasi Shakti Adhikar Manch (DASAM) and Justice News in collaboration with National Alliance of People’s Movement (NAPM), National Campaign for Dignity and Rights of Sewerage and Allied Workers (NCDRSAW), Sewerage and Allied Workers Forum (SSKM), Delhi Solidarity Group (DSG), Indian Sanitation Studies Collective (ISSC) and Vimarsh Media. The speakers at the press conference also pointed out that the poor condition of sewer and sanitation workers, who largely belong to marginalised caste groups, also shows the persistence of caste based exploitation in India. They said that deaths of sewer/septic tank workers are not new in this country but most of these cases go unacknowledged by the government authorities and are suppressed by the police.

Manual scavenging is also a violation of Article 21 of the Constitution which guarantees the right to live with dignity. The Prohibition of Employment as Manual Scavengers and their Rehabilitation Act, 2013 doubly reinforces this right by making manual scavenging an outlaw practice. However, even after a decade of its implementation, this caste-based practice continues to exist within the nation and take the lives of uncountable people.