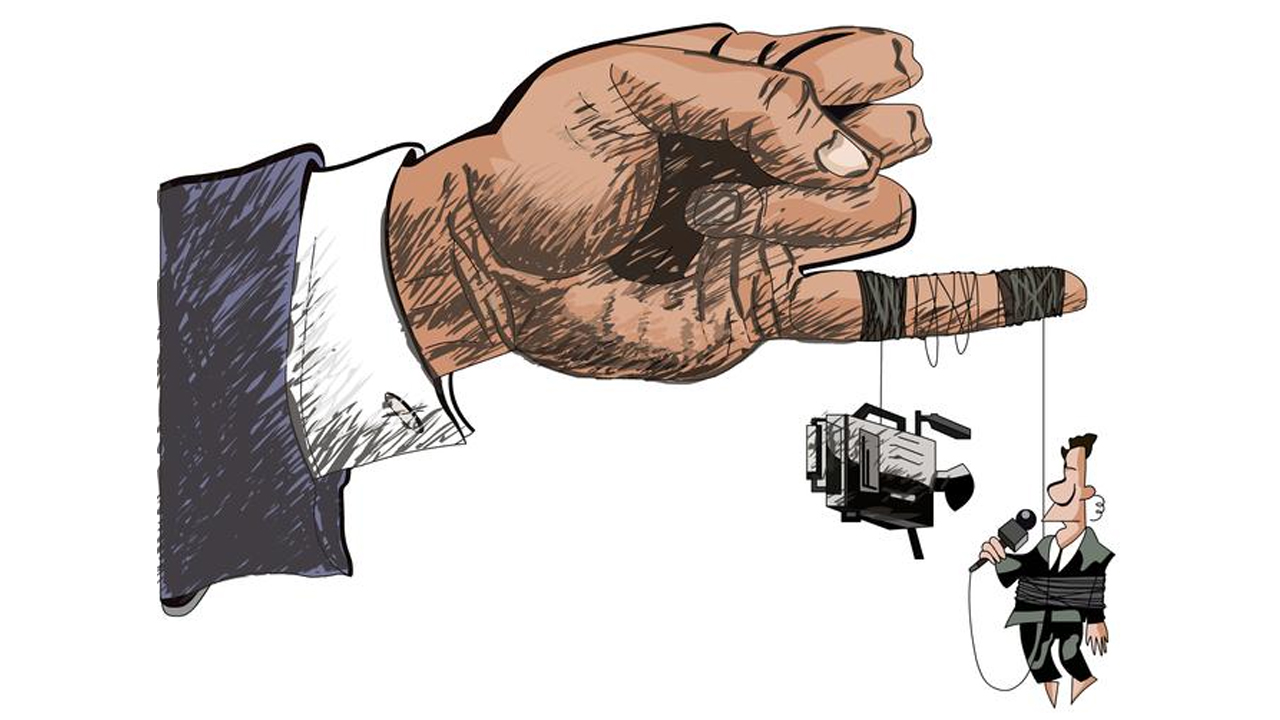

Press freedom in India has been badly hit by the gobbling up of media platforms by a few large companies. Large and powerful corporate houses have exercised diverse strategies to acquire several well-established media companies. What has arguably worked to favour them is their closeness to Narendra Modi’s government.

By R Srinivasan

Published on May 3, 2024

December 30, 2022, was a day to forget for India’s already badly mauled and tamed media.

For, that day, influential – and, for many, controversial – Indian businessman Gautam Adani, then the world’s third richest man, took nearly full control of the much-respected and revered NDTV after his Adani Enterprises acquired 27.26 percent additional shares, taking his total holdings to 64.71 percent.

A few months before delivering this coup de grace, Adani’s media company, AMG Media Networks, had hired a new CEO and a retinue of government-friendly journalists.

His tail up, Adani’s next target was The Quint which, like NDTV, wore its anti-establishment badge with pride. On March 27, 2023, AMG Media Networks acquired 49 percent stake in Quintillion Business Media Pvt Ltd, The Quint’s holding company. This happened five years after central tax authorities raided The Quint’s offices in Noida, Uttar Pradesh.

Over the last 15 years or so, large and powerful corporate houses such as Mukesh Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd (RIL) and Adani Enterprises have exercised diverse strategies to acquire several well-established media companies.

What has arguably worked to favour the Ambanis and the Adanis is their closeness to Narendra Modi’s government.

While one 2019 report said that Reliance “controlled” 72 television channels across India, the company does not shy away from claiming that it has an “omni-channel presence”. This brings to sharp relief the issue of diversity, or the lack of it, in Indian media.

The government has made no secret of its intent to control the media narrative.

India leads the world in government-ordered takedowns of social media posts across platforms like YouTube, micro-blogging platform X (formerly Twitter) etc.

Recently, X blocked dozens of accounts backing farmers protesting government policy on agricultural prices, while journalists and media outlets perceived as being “unfriendly” to the Modi government have faced arrests, tax raids and other coercive action by government agencies.

On paper, India is one of the world’s largest and most diverse media markets. There are more than 140,000 registered newspapers and periodicals, of which more than 22,000 are daily newspapers. These are published in an astonishing 189 languages and dialects, covering not only all the multiplicity of tongues, but many foreign languages as well.

There are more than 900 television channels, of which more than 350 are news channels, with a majority of them broadcasting 24/7. India also has more than 850 FM radio channels, of which only the state-owned All India Radio is officially allowed to broadcast news.

Rapid expansion in broadband internet access has also led to an explosion of digital news media outlets.

While there are no estimates of the number of digital news media sites in India, many of the legacy print publications and TV news channels also have a digital presence, while the number of digital only news sites continues to soar with rising internet penetration. At last count, India had more than 820 million active internet users.

There is, however, another yardstick which is of more fundamental importance to plurality of news and opinion – media ownership.

Organised mass media is no longer the purvey of journalist-entrepreneurs. It is a large scale business requiring heavy capital investment and lots of working capital. This has increasingly led to a growing corporatisation of media – in India and elsewhere – bringing large business conglomerates into play as media owners.

While the takeover of major Indian media networks by large corporate conglomerates is legion, increasing control by business houses poses a threat to the untrammelled working of the media. A problem which has been recognised elsewhere too.

Two years ago a senior Bangladeshi editor of an English newspaper wrote: “As our business houses increase in number, they are investing resource and power, into newspapers (read media in general) that can serve as a part of their arsenal for business growth, fighting rivals and frightening others from exposing their malpractices.”

It is a no-brainer why business houses seek to control media.

First, there are collateral benefits of proximity to the powers-that-be. Second, there is the attraction of posting greater profits.

One estimate pegs the Indian media and entertainment sector’s revenues to hit about Rs 2.6 trillion (USD$31.15 billion) this year. Another estimate states that by 2026, India will be the world’s fifth largest media market by value, in both print and broadcast television. Such mammoth numbers make media a legitimate focus of interest for businesses.

However, a consequence of this growing corporatisation has been the dominance of business interests in the decision-making processes in media houses, which has hampered editorial independence.

Heavy reliance on advertising revenues is the other threat to genuine media independence.

In 2022, while Indian print media generated Rs 165.95 billion (USD$1.9 bn) in advertising revenues, circulation revenues were only a fraction of this at an estimated Rs 76.30 billion (USD$0.9 bn).

This means that advertising – and as a corollary, the need to keep advertisers happy – is of prime importance, further weakening the freedom of editors and journalists. This is true for broadcast television, which has seen advertising revenues rise while subscription revenues have fallen.

No less significant is the rise of publicly listed media enterprises, with a large number of public shareholders. With managements under pressure to deliver dividends to shareholders, the pursuit of profit is the paramount objective.

Increasingly blurred lines across channels – both newspapers and TV channels also run websites, which compete with similar digital-only websites – has meant that news is no longer news – it is content.

And what content is produced and presented is driven more by algorithms than the informed decisions of editors. This has changed the reader/viewer from a citizen and a key stakeholder in the democratic process to a consumer and a target for advertisers.

But perhaps the most singular threat to a diversity of voices in the media is posed by the growing concentration of media ownership in the hands of a few.

A 2018 a research project found that the print media market is highly concentrated. Just four publications – Dainik Jagran, Hindustan, Amar Ujala and Dainik Bhaskar – capture three out of four readers in Hindi.

With no laws or regulations in India on cross-holdings, a few powerful conglomerates now control a significant slice of the media audience in India.

This makes it easier for vested interests to assert control through opaque and non-public means and reduces plurality and diversity in the marketplace.

R Srinivasan is a Professor of Practice at the School of Journalism and Communication, O P Jindal Global University, Sonipat, Haryana. He has been a senior journalist, having worked for The Hindu Business Line, Mail Today, Hindustan Times, The Times of India, Indian Express and Business Standard among others, in a career spanning over 30 years. The views expressed here are the writer’s own.

Originally published under Creative Commons by 360info™.