Belafonte remained steadfast in his belief that the only songs worth singing are those which acknowledge the struggle of ordinary people against injustice and poverty. His greatest works were the democratic anthems of the struggle of the 2 billion against the millionaires, which pointed the way towards today’s struggle of the 8 billion against the billionaires. Dennis Redmond pays tribute to Harry Belafonte.

The passing of Harry Belafonte (1927-2023), one of the 20th century’s titanic artists, marks the end of an era for two reasons. Firstly, he was part of a generation of progressive artists who catalyzed the rise of transnational cultural production in the United States between 1945 and 1973. Belafonte’s own contribution was to transform the Caribbean popular musical form of calypso into a transnational art-form, catapulting him to the status of the first African American television star.1

The other noteworthy members of the same generation included Pete Seeger, the musician who transformed folk songs from obscure relics of the past into one of the staple genres of late 20th century American popular music; Sidney Poitier, the great actor who became the first African American superstar of Hollywood cinema; and Leonard Bernstein, the world-class conductor who popularized the works of late 19th and early 20th century European musical industrial modernism throughout the United States and later among transnational audiences.2

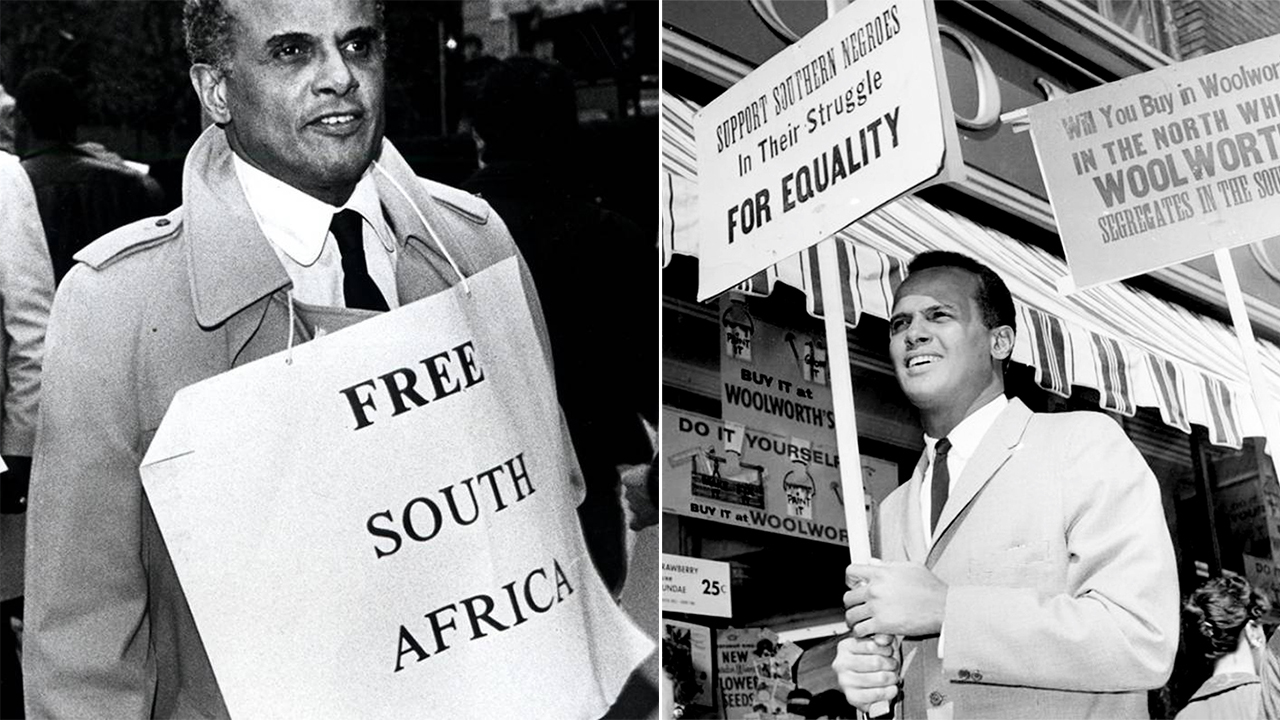

Secondly, Belafonte set the model of the socially committed media artist of the second half of the 20th century. Instead of resting on his laurels as a media star, he became a key confidante of Martin Luther King, Jr. and served as a staunch supporter of the US civil rights struggle of the 1950s. During the 1960s and 1970s, Belafonte protested against the Vietnam War while mobilizing support for the anticolonial movements of Africa and Asia. During the 1980s and 1990s, he was a key figure in the international campaign which ended South Africa’s apartheid regime.

The heart of this commitment to democracy was Belafonte’s profound cosmopolitanism. He was receptive to all forms of musical aesthetic creativity from all over the world, something especially remarkable at a time when the world’s mass media was dominated by a handful of US corporations. One the most obvious expressions of this cosmopolitanism was Belafonte’s legendary generosity to the young artists who followed in his wake. He helped to launch the musical career of South Africa’s Miriam Makeba, and remained a mentor figure to progressive artists, musicians and activists all across the world until the very end of his life.

This cosmopolitanism was rooted in Belafonte’s biographical experience of being born into excruciating poverty in Harlem, New York City, and living with his extended family in British-colonized Kingston, Jamaica, between the ages of five and thirteen. Throughout the 20th century, New York was a key center of African American blues and jazz music while Kingston was a center of mento, calypso and other staples of Afro-Caribbean popular music. Belafonte would draw extensively from both of these musical continuums throughout his musical career, crossing musical borders in the same way he crossed the barriers of race and nationality.

In 1940, Belafonte returned to live with his parents in New York City, dropped out of high school and enlisted in the US Navy in 1944. His experience as a soldier profoundly radicalized him, due in part to the bitter personal experience of the racial segregation typical of the pre-1945 US armed forces (while Kingston and New York City were deeply racist cities, they did not have Jim Crow policies enshrining racism as state law), but also to the African American soldiers he met who hailed from all across America. The more educated of these soldiers taught him the basics of politics and history, and motivated him to begin to read widely at a local public library.3

After leaving the Navy in December 1946, Belafonte attended a theatrical performance at the American Negro Theater (ANT), a small progressive African American theater group, very much by chance – and was instantly enthralled. He became a volunteer actor with the ANT and befriended Sidney Poitier, at that time a penniless youth who had grown up in the Bahamas and dreamed of becoming an actor.

The ANT also gave Belafonte the chance to meet the legendary artist Paul Robeson in person. This meeting inspired Belafonte to take acting seriously as a career, and he subsequently enrolled at the Dramatic Workshop of the New School for Social Research from 1946 until 1948. His classmates at the Workshop included future luminaries such as Bea Arthur, Marlon Brando, Wally Cox, Tony Curtis (originally named Bernard Schwartz), Walter Matthau, Rod Steiger and Elaine Stritch.

When not working at the theater, Belafonte spent many of his off hours at the Royal Roost, a local nightclub which hosted some of the greatest jazz musicians of the 1940s.4 These musicians accidentally overheard him giving impromptu singing performances, realized he had a musical gift, and convinced him to try performing live. In his memoir, Belafonte described his debut as a singer as follows:

And then something very odd happened, something I remember as vividly today as when it happened more than sixty years ago.

Tommy Potter came out onstage [at the Royal Roost] with us, picked up his bass, and started playing along. I looked at him, surprised and confused. He gave me a nod and a smile.

Then Max Roach glided out and slid behind his drum set.

And finally Charlie Parker emerged from backstage and picked up his sax.

Al Haig, Tommy Potter, Max Roach… and Charlie Parker!

I couldn’t believe it. Four of the world’s greatest jazz musicians had just volunteered to be the backup band for a twenty-one-year-old singer no one had ever heard of, making his debut in a nightclub intermission.5

Belafonte’s combination of stage presence, Jamaican-American musicality and artistic intensity was an instant hit with the crowd. What he could not have known at the time, but realized only decades later, was that his performance occurred at just the right time and place to launch a national career:

I had a voice the crowd liked, and a look. “The Gob with a Throb,” as one nightlife columnist dubbed me. But I could have sung those songs in a hundred other jazz joints around the country and gone nowhere. The [Royal] Roost wasn’t just another joint. In the winter of 1949, it was the epicenter of jazz, a birthplace of bebop, its nightly torrent of hot licks broadcast live around the country from a glassed-in booth in the back of the club by radio’s premier jazz DJ, Symphony Sid. And it was Symphony Sid, as much as Monte Kay, who helped launch me.

‘This is your man Symphony, Symphony the Sid, your all-night, all-frantic one…’ Symphony Sid, born Sidney Tarnopol on the Lower East Side, had become the ‘dean of jazz,’ a white hipster who introduced black jazz stars to mass radio audiences. He had a regular show on WJZ, which Lester Young promoted in his song Jumpin’ [Jumping] with Symphony Sid (“The dial is all set right close to eighty…”). But in a collaboration with Monte, he often broadcast live from the Roost. That first week of my intermission gig, Sid presided from his booth in back, telling his fans to listen. “Down here at the Royal Roost, a lot of exciting stuff going on, we got an exciting singer here, Harry Belafonte. Now this is a great story, folks… One week ago he was in the garment district pushing a rack of clothes. Now he’s packin’ ’em [packing them] in at the Roost! It’s a Cinderella story, is what it is, which is why we call him… the Cinderella Gentleman!”

That first week, Monte and Symphony Sid became my co-managers, and the Roost’s publicist, Virginia Wicks, became my publicist.6

This was the beginning of Belafonte’s ascent to musical superstar status, which culminated in 1956 with the release of his iconic album, Calypso. This latter sold a million copies, an unprecedented number for a music album. Belafonte leveraged his commercial success to land roles in films such as Carmen Jones (1954), Island in the Sun (1957), and Odds Against Tomorrow (1959), and went on to found his very own media production company. However, one of his most important subsequent contributions was a series of ground-breaking television broadcasts.

One of the first of these was his electrifying performance of Jamaica Farewell on the Ed Sullivan Show during 1956, wherein Belafonte delivered Irving Louis Burgie’s extraordinary lyrics:

Down at the market you can hear

Ladies cry out while on their heads they bear

Ackee [Jamaican fruit], rice, salt fish are nice

And the rum is fine any time of year

Ackee with saltfish is widely considered to be Jamaica’s national dish, while rum is still one of its most important agricultural exports. Yet far from invoking the stereotypical figures of the illiterate, drunken Afro-Caribbean fisherman or farmer, Belafonte’s onscreen persona radiated intelligence and urbanity. Nor is it difficult to read the refrain of the song (“My heart is down, my head is turning around / I had to leave a little girl in Kingston town”) as the very personal expression of Belafonte’s childhood attachment to – and adult distance from – British-colonized Jamaica.7

His spectacular television performances convinced CBS to sponsor his own one-hour television special, Tonight with Belafonte, broadcast in 1959. This was one of the most remarkable televisual works of its time, with dance numbers featuring Mary Hinkson and Arthur Mitchell, musical performances by Odetta, Brownie McGee and Sonny Terry, and Belafonte’s own classic rendition of the folk song John Henry.8

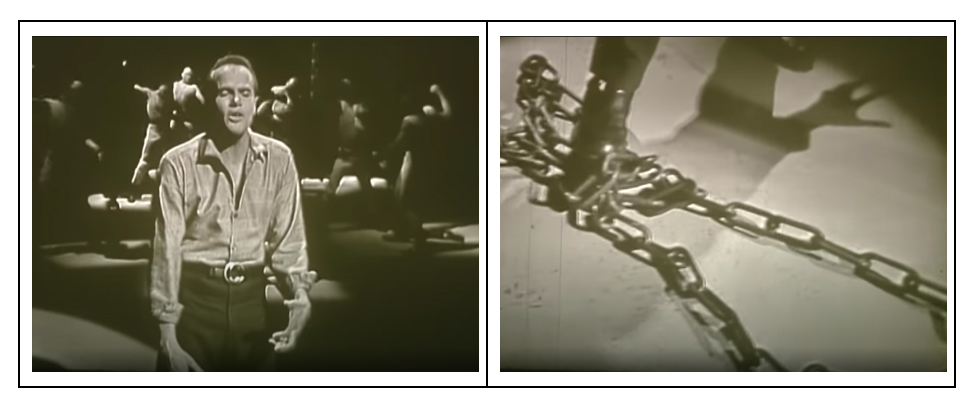

The opening song of the broadcast featured Belafonte framed against a group of dancers performing a dance in the background. It ended with the spoken lyric, “Hold that line” and the camera focused on Belafonte’s foot stamping on iron fetters, evoking the smashing of slave shackles. Both moments are shown in Figure 1 below:

Figure 1. Screenshot of Belafonte silhouetted against a dance troupe on the left, screenshot of the breaking of slavery’s chains on the right.

This sequence was scandalous in 1959, when the US civil rights struggle was still just beginning to win victories and had not yet become the irresistible mass movement it would become in the 1960s. A later dance sequence later in the broadcast was even more shocking, because it openly defied the norms of segregation still enforced by the bulk of US television programming. Two moments from this sequence are shown in Figure 2:

Figure 2. Belafonte performs with a multiracial cast, screenshot below left. The dancers include white Americans, African Americans as well as Asian Americans, screenshot below right.

What made Belafonte such a charismatic figure on stage as well as on the television screen was his dignity as a performer. Whereas generations of previous African American musicians and stars had been compelled to display docile or deferential body language for the benefit of deeply racist white audiences, Belafonte was the bodily personification of wit, playfulness and sheer joy.

He did not sing for the approval of the largely white audiences of his day, but as a means of communicating with the transnational audiences of the future. His gestural language of freedom was decades ahead of its time, and one could argue that the first African American performer to instantly command the television screen the same way Belafonte did was Eddy Murphy’s inaugural appearance on The Johnny Carson Show in 1982.

For the rest of his career, Belafonte would eschew money-making commercialism in favor of progressive engagements with audiences and communities of artists. One of the most famous of these engagements was Belafonte’s week-long stint as the guest host of Johnny Carson’s The Tonight Show from February 5 to 9, 1968, wherein he interviewed a host of luminaries which included Martin Luther King, Jr. and Senator Robert F. Kennedy, both destined to fall to assassins’ bullets later that same year.

In the field of cinema, Belafonte did a famous turn as the co-star of Sidney Poitier’s cult classic Buck and the Preacher (1972). This latter was one of the first revisionist Westerns of the 1970s to feature African American cowboys, four decades before Quentin Tarantino’s Django (2012). Five years later, Belafonte’s final album, Turn the World Around (1977), integrated musical motifs from Fela Kuti’s Afrobeat and Ghana’s popular music form of high life. In the 1980s, Belafonte’s media company produced Stan Lathan’s Beat Street in 1984, the independent film which helped to popularize the early 1980s hip hop culture of New York City.

Perhaps the most interesting of Belafonte’s projects was his attempt to construct an archive of African American popular music dating from the foundation of the North American colonies in the 17th century to the present. The project began in 1961, but ground to a halt a decade later due to a lack of interest from record companies. The materials Belafonte collected over decades were eventually published as The Long Road to Freedom: An Anthology of Black Music in 2001. While many of the songs are classic works of African American culture, the interpretive texts accompanying the recordings are uneven.

One of the tasks of the future will be to rethink and reflect on the archive Belafonte and the other progressive artists of the 20th century left for us here in the early 21st century. It is worth remembering that Belafonte was born at a time when there were only 2 billion people on the planet, the majority of whom lived in rural communities and were ruled by ten despotic empires. He passed away at a time when there are 8 billion people on the planet, the majority of whom live in cities and are citizens of almost two hundred polities.

Despite these sweeping changes, Belafonte remained steadfast in his belief that the only songs worth singing are those which acknowledge the struggle of ordinary people against injustice and poverty. His greatest works were the democratic anthems of the struggle of the 2 billion against the millionaires, which pointed the way towards today’s struggle of the 8 billion against the billionaires.

………………….

1 Among other landmarks, Belafonte was the first African American to win a Tony Award for his acting in 1954 and the first to win a Grammy Award for his music in 1961.

2 It was no accident that Belafonte, Poitier and Seeger all became close friends and contributed mightily to the Civil Rights struggle and to the anti-Vietnam War protest movements. It is Bernstein’s credit that he, too, was a lifelong supporter of the Civil Rights struggles and other progressive causes, something Belafonte acknowledged in a 2011 interview: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1vbnG00ojY4&t=22m7s.

3 Belafonte has provided a vivid description of his politicization as a soldier in his autobiography. See: Harry Belafonte. My Song: A Memoir. With Michael Schnayerson. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011. Chapter 4.

4 Belafonte recounted the story of his debut as a singer in a 2011 interview, available online here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1vbnG00ojY4&t=6m15s

5 Harry Belafonte, My Song. Chapter 5.

6 Harry Belafonte, My Song. Chapter 5.

7 Jamaica would not gain its independence from the British empire until 1962.

8 Judith E. Smith. Becoming Belafonte: Black Artist, Public Radical. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2014 (203-206