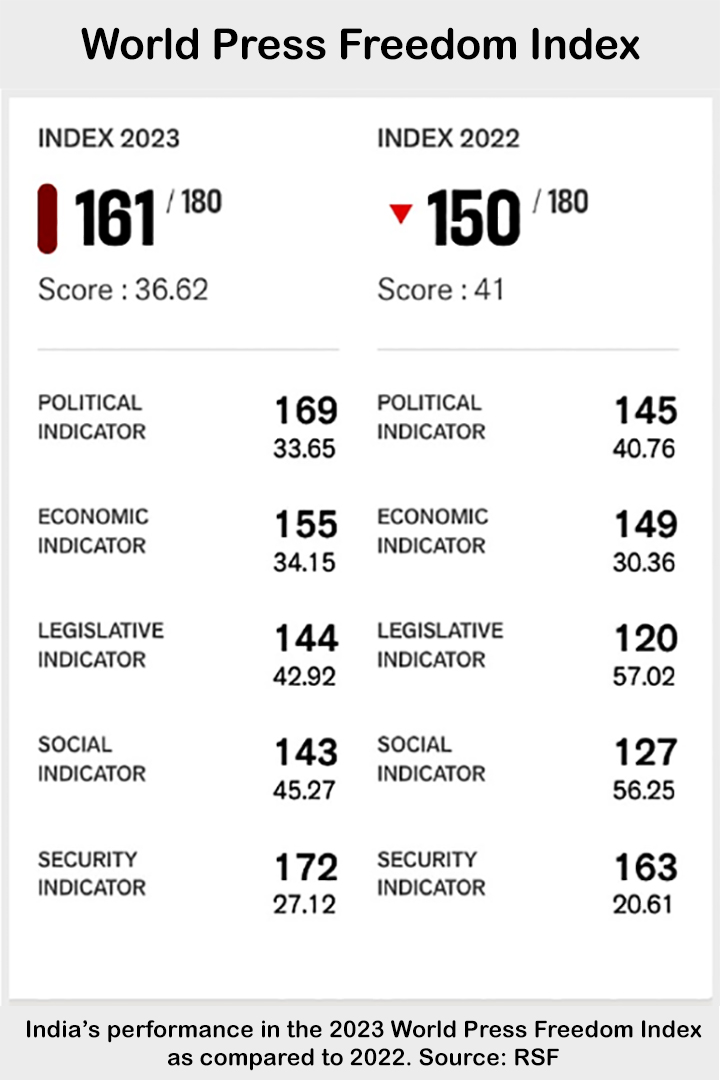

Reporters Without Borders (RSF), a global media watchdog, released the 21st edition of its World Press Freedom Index on Wednesday (May 3). India has slipped to the 161st position in terms of press freedom out of 180 countries ranked in the report.

The RSF, an international NGO headquartered in Paris, comes out with a global ranking of press freedom every year. The objective of the World Press Freedom Index, “is to compare the level of press freedom enjoyed by journalists and media in 180 countries and territories” in comparison to the previous calendar year. According to the 2023 World Press Freedom Index, the situation is “very serious” in 31 countries, “difficult” in 42, “problematic” in 55, and “good” or “satisfactory” in 52 countries.

While India has ranked consistently low over the past few years, its rank has plunged to the lowest this year. India finds itself among the 31 countries where RSF believes the situation for journalists is “very serious”. India is 11 spot worse than 2022, when it stood at 150.

The section on India starts with RSF stating:

“The violence against journalists, the politically partisan media and the concentration of media ownership all demonstrate that press freedom is in crisis in “the world’s largest democracy”, ruled since 2014 by Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the leader of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP) and the embodiment of the Hindu nationalist right.”

The RSF ranking of press freedom is based on five different categories that are used to calculate scores and rank countries. These five broad categories are: political context, legal framework, economic context, socio-cultural context and safety (of journalists). Of the five categories, the most concerning is India’s ranking of 172 in the Security indicator category. This means, only eight countries out of 180 are worse than India when it comes to ensuring the safety and security of journalists. Since January 1, 2023 one journalist was killed in India while 10 journalists are behind bars. With an average of three or four journalists killed in connection with their work every year, India is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for the media,” the report stated. In terms of safety parameter, India is ranked worse than all other countries except for China, Mexico, Iran, Pakistan, Syria, Yemen, Ukraine, and Myanmar, with Myanmar having the lowest ranking.

Overall, India’s performance is poor compared to even Pakistan which ranks ahead of India at 150. Bangladesh is slightly worse than India at 163 rank. Sri Lanka made significant improvement on the index, ranking 135th this year as against 146th in 2022. Surprisingly, even Afghanistan (at 152) has a better ranking than India.

The five different categories used to calculate scores and rank countries are given below from the report.

Media landscape

The Indian media landscape is like India itself – huge and densely populated – and has more than 100,000 newspapers (including 36,000 weeklies) and 380 TV news channels. But the abundance of media outlets conceals tendencies toward the concentration of ownership, with only a handful of sprawling media companies at the national level, including the Times Group, HT Media Ltd, The Hindu Group and Network18. Four dailies share three quarters of the readership in Hindi, the country’s leading language. The concentration is even more marked at the regional level for local language publications such as Kolkata’s Bengali-language Anandabazar Patrika, the Mumbai-based daily Lokmat, published in Marathi, and Malayala Manorama, distributed in southern India. This concentration of ownership in the print media can also be observed in the TV sector with major TV networks such as NDTV. The state-owned All India Radio (AIR) network owns all news radio stations.

Political context

Originally a product of the anti-colonial movement, the Indian press used to be seen as fairly progressive but things changed radically in the mid-2010s, when Narendra Modi became prime minister and engineered a spectacular rapprochement between his party, the BJP, and the big families dominating the media. The prime example is undoubtedly the Reliance Industries group led by Mukesh Ambani, now a personal friend of Modi’s, who owns more than 70 media outlets that are followed by at least 800 million Indians. Similarly, the takeover of the NDTV channel at the end of 2022 by tycoon Gautam Adani, who is also very close to Narendra Modi, signalled the end of pluralism in the mainstream media. Very early on, Modi took a critical stance vis-à-vis journalists, seeing them as “intermediaries” polluting the direct relationship between himself and his supporters. Indian journalists who are too critical of the government are subjected to all-out harassment and attack campaigns by Modi devotees known as bhakts.

Legal framework

Indian law is protective in theory but charges of defamation, sedition, contempt of court and endangering national security are increasingly used against journalists critical of the government, who are branded as “anti-national.” Under the guise of combatting Covid-19, the government and its supporters have waged a guerrilla war of lawsuits against media outlets whose coverage of the pandemic contradicted official statements. Journalists who try to cover anti-government strikes and protests are often arrested and sometimes detained arbitrarily. These repeated violations undermine media self-regulatory bodies, such as the Press Council of India (PCI) and the Electronic Media Monitoring Centre (EMMC).

Economic context

The Indian press is a colossus with feet of clay. Despite often huge stock market valuations, media outlets largely depend on advertising contracts with local and regional governments. In the absence of an airtight border between business and editorial policy, media executives often see the latter as just a variable to be adjusted according to business needs. At the national level, the central government has seen that it can exploit this to impose its own narrative, and is now spending more than 130 billion rupees (5 billion euros) a year on ads in the print and online media alone. Recent years have also seen the rise of “Godi media” (a play on Modi’s name and lapdogs) – media outlets such as Times Now and Republic TV that mix populism and pro-BJP propaganda. The old Indian model of a pluralist press is therefore being seriously challenged by a combination of harassment and influence.

Sociocultural context

The enormous diversity of Indian society is barely reflected in the mainstream media. For the most part, only Hindu men from upper castes hold senior positions in journalism or are media executives – a bias that is reflected in media content. For example, fewer than 15% of the participants in major evening talk shows are women. At the height of the Covid-19 crisis, some TV hosts blamed the Muslim minority for the spread of the virus. The media landscape is nonetheless also rich in alternative examples such as Khabar Lahariya, a media outlet composed solely of female journalists from rural areas and from ethnic or religious minorities.

Safety

With an average of three or four journalists killed in connection with their work every year, India is one of the world’s most dangerous countries for the media. Journalists are exposed to all kinds of physical violence including police violence, ambushes by political activists, and deadly reprisals by criminal groups or corrupt local officials. Supporters of Hindutva, the ideology that spawned the Hindu far right, wage all-out online attacks on any views that conflict with their thinking. Terrifying coordinated campaigns of hatred and calls for murder are conducted on social media, campaigns that are often even more violent when they target women journalists, whose personal data may be posted online as an additional incitement to violence. The situation is also still very worrisome in Kashmir, where reporters are often harassed by police and paramilitaries, with some being subjected to so-called “provisional” detention for several years.