The country is far away from the ideas of non-communal secular republican democratic India that they dreamt of. All shades of democratic rights, freedom of expression are being taken away today. At this time, it is the responsibility of the present generation to carry on the legacy of the revolutionary tradition of Masterda and his fellow comrades. In the struggle to fulfill the unfulfilled dreams, let the lessons be learnt from the supreme sacrifices of the leaders like Masterda Surya Sen and the thousands of revolutionaries, writes Bikash Ranjan Deb.

18 to 22 April in 1930, were a few exceptional days in the last phase of India’s anti-colonial movement. An unforgettable chapter was written in course of the revolutionary movement of India between the Chittagong Youth Uprising of 18 April and the Jalalabad hill battle of 22 April under the leadership of ‘Sarvadhinayak‘ Masterda Surya Sen. Scores of revolutionary heroes, men and women alike, who took part in this youth rebellion, fell to the bullets of the foreign ruler or were sent to the gallows; countless put into prison; hundreds of men and women, young and old, were tortured by the British police and military. They had jumped into the rebellion with the dream to break the shackles of subjugation, uttering the oath — ‘জীবন মৃত্যু পায়ের ভৃত্য, চিত্ত ভাবনাহীন’ (life & death is like servant, the mind is careless!). In their voice one can hear the bold utterance of the rebel poet, Kazi Nazrul, — ‘আমি দ’লে যাই যত বন্ধন, যত নিয়মকানুন শৃঙ্খল! আমি মানিনা কো কোন আইন’ (I break all the bondages, all the rules and chains! I do not follow any rule). So, they were fearless, ‘কেবা প্রাণ করিবেক দান’ (Who would be sacrificing his life first)! Today, nine decades later, standing in another month of April, the struggle of those great revolutionaries can be remembered afresh.

If we look back a little to the beginning of the revolutionary movement in India, we will notice that in the period 1904-1934, a series of anti-British armed struggles developed in various parts of the undivided country. A number of revolutionary parties played a very important role in the course of this armed resistance — Anushilan Samiti, Jugantar, Hindustan Republican Association (HRA) (later Hindustan Socialist Republican Association-HSRA) and similar revolutionary parties and organizations. Modelled on the methods and examples of the revolutionary movements and secret societies of the West, the national revolutionaries, during the period 1904-1934, were involved ‘in organizing secret societies, anti-imperialist indoctrination of their members, physical and moral training, collection of fire-arms, collection of funds by dacoities, assassination of enemies and traitors by bombs and fire-arms’.

However, in spite of near unanimity among the writers on the national revolutionary movement as to the methods and aims of the revolutionaries, there have been marked differences among them over the issue of choice of a proper term for identifying the same movement. In Britain, the term ‘terrorist’ or ‘terrorism’ was popularized by British administrators who worked in India, for instance, Tegart’s speech at the Royal Empire Society, London on November 1, 1932, and subsequent publication of ‘Terrorism in India’ pointed to a particular type of picture of revolutionaries of India, specially of Bengal. (Tegart, 1933/1983) Leaving aside the British-sponsored label of ‘terrorism’, a term generally used in a derogatory sense, we shall call this movement ‘revolutionary nationalism’.

The national revolutionary movement in India mainly spanned for almost thirty years (1904-1934). But this does not mean that it had not its beginning a few years back and it did not continue even after 1934. The duration has been kept confined to these thirty years only to indicate that during this period, the national revolutionary movement was at its peak though sometimes it also passed through a period of slumber. We may discuss the whole process of the national revolutionary movement in four phases keeping in mind its origins, tactics and strategies adopted, formation of alliances with other such groups and finally, the intensity of their efforts to liberate the country by way of armed rebellion. The four phases may be as follows: (A) The First Stage from 1897 to 1914; (B) The Second Stage from 1914 to 17; (C) The Third Stage from 1921 to 1927; (D) The Fourth Stage from 1928 to 34. After 1934, almost all the revolutionary leaders and activists were either imprisoned or interned. Most of them were released in 1937-38, although the Andaman prisoners were released in 1946. While imprisoned, through collective readings and discussions, the revolutionaries came to the realisation that their achievements had been disproportionately small compared to their sacrifices. They felt that national revolutionary movement failed to reach its logical culmination. As a result, by the thirties of the 20th century, a large number of national revolutionaries started feeling that their ‘exclusively petty-bourgeois movement … had reached its climax’. It could not develop further. After coming out of prison, these revolutionaries turned away from the path of individual terrorism, from the path of armed struggle; but they did not leave the path of struggle. In 1938, the Jugantar and Hindustan Socialist Republican Association officially announced the dissolution of the party. The Anushilan Samiti, though, did not announce the abolition of the party but also did not stick to the old methods. So, the national revolutionaries started engaging themselves in search of a new ideology and program. A distinct swing towards Marxism was noticed clearly in many of the Indian national revolutionaries. Most of the revolutionaries who still remained active were drawn to Marxism after their release from prison, and pledged to complete their unfinished work guided by Marxist philosophy. Some of the revolutionaries, however, either joined political parties of the time or formed a new party themselves. But no one went back to the old methods of armed struggle.

An oppressive foreign rule, economic crisis, the awakening of national consciousness and the restrictive conciliatory policy of the then Congress leadership may be said to have constituted the four main ingredients for the emergence of radical nationalism and its subsequent violent manifestations among the educated youth of India. The Mahabharata, the Gita and the two festivals promulgated by Tilak, the Shivaji Festival and the Ganapati Festival, laid the foundation of radical nationalism in Maharashtra. Similarly, in Bengal — the Goddess of power, Kali and Durga, were seen as the fountainhead of nationalism by leaders like Bepin Chandra Pal. The radical nationalist ideology and movement reflected a combination of militancy and orthodox Hinduism. Tilak, Bepin Chandra Pal, Aurobindo Ghosh, Lajpat Rai and the other extremist leaders encouraged the use of religious idiom as a medium of mass contact. Tilak founded a cow-protection association and organised Ganapati and Shivaji Festivals to rally the Hindu sentiment. Aurobindo equated Goddess Durga with the motherland. This tradition of relying upon Hindu heritage and past glory was also visible in the ideas and activities of the national revolutionaries which resulted in the alienation of other religious groups from this movement. Further, the life and works of the great Italian revolutionary Giuseppe Mazzini greatly inspired them. The Bengal revolutionaries were also influenced by the Italian Risorgimento, by the Nihilist movement in Russia and by the Sinn Fein movement in Ireland.

June 22, 1897, saw the advent of the idea of political assassination and the cult of bomb as a form of revolutionary nationalism or the ‘Age of Fire’ (Agniyug). On that day, in Poona, Maharashtra, Chapekar brothers assassinated Mr. Rand, the then Plague Commissioner of Poona. The Chapekars were sentenced to death, but the spirit was far from being crushed. Revolutionary secret societies continued their silent activities in that region of India through ‘akhras’ or physical exercise clubs which also arranged for the study of the literature of European secret societies and anarchism. Even in the face of brutal British repression, the revolutionaries of Maharashtra continued to pursue their goal of building up a network of activists to target notorious British officials — to terrorise the colonial administration. Revolutionaries became very active, particularly in Poona, Nasik, Satara and even in places like Gwalior, Kathiwad, Baroda — all Maratha bastions. A number of violent action-programs either had been undertaken or planned. The police tried hard to suppress the dissemination of militant activities of the revolutionaries. Most of the leaders and workers were arrested and many of them were implicated in Poona, Nasik and Satara trials. This led to the gradual weakening of revolutionary activities in Maharashtra.

But, violent acts of militant nationalism were spreading across other parts of India, particularly in Bengal, during the same period. The tactics of political assassination as a weapon of militant nationalism in Bengal at the beginning of the twentieth century seemed to have been imported from Maharashtra. Aurobindo Ghosh and Jatindranath Bandyopadhyay were the harbingers. As a part of a long-term strategy, they first encouraged the setting up of gymnasiums to train the youth as bodybuilders and in the skills of fighting with sticks and daggers. Secret societies had indeed already appeared in Bengal though they were not yet prepared for terrorist activities or direct action against the foreign rulers. Anushilan Samiti (1902), Atmonnati (1897) and Suhrid Samiti (1901), Dawn Society (1902), Bandhab Sammilani (1902), Friends United Club (1902), were perhaps the earliest Samitis formed with a vague idea of freedom of the country, but primarily – if not solely – engaged in body-building physical culture. The Anushilan Samiti was the most prominent among all these organisations. Anushilan Samiti was established by Pramathanath Mitra; a section of Anushilan was later reorganized under the banner of Jugantar. The message of revolutionary politics in East Bengal was spread by the Dhaka Anushilan Samiti led by Pulin Das. A festival of self-sacrifice started in Bengal. First Kshudiram and Praful Chaki; then one after another revolutionary acts and a frenzy of life-sacrifice. Kanailal Datta, Satyendra Bose, Charu Chandra Bose, Birendranath Dattagupta, Basanta Biswas, Baghajatin, Chittapriya Raychoudhury, Gopinath Saha, Jatin Das and so many other young people became martyrs. It is against this backdrop that an attempt can be made to analyze the significance of the revolutionary activities of Masterda Surya Sen and the Indian Republican Party led by him.

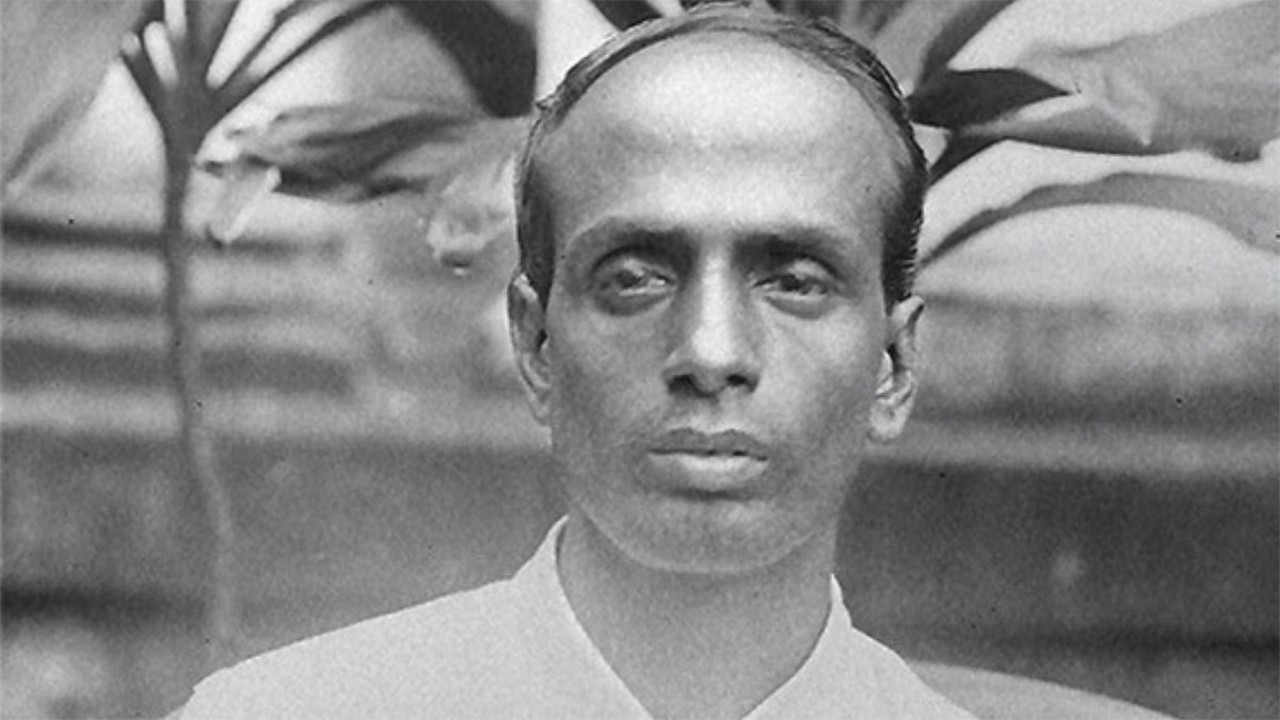

Masterda Surya Sen was one of the most illumining leaders in the history of the revolutionary struggle of colonial India. Masterda was martyred at the age of 39; he was the oldest leader of his party at the time of Chittagong youth rebellion, his age being 36 years. Kalpana Dutta writes, this young teacher took himself to such a height that he built a disciplined revolutionary organization with more than five hundred fearless youth in Chittagong district alone. And that too with such secrecy that most of them could keep themselves unknown as revolutionary activists even to the police. For almost three years after the youth uprising, Masterda could evade arrests despite frantic efforts of the British police and army. Had it not been for the betrayal of a fellow countryman, he might have been able to avoid arrest for a longer time and carry forward the revolutionary movement. So strong was the organizational structure of the party; so much was the love and passion of the common villagers of Chittagong for him. So Masterda was not only the kind of leader whom we call a leader in the general sense, he was a ‘leader of leaders’.

Masterda Surya Sen first came in contact with revolutionary politics in 1916. He studied intermediate courses at Chittagong College for two years and performed very well in the exam and wanted to study BA there. But due to some reason, he got displeased with the college authorities and he was given a transfer as his behaviour was, stated to be, reprehensible, ‘Bad conduct’- as has been declared by the college authorities. So, he came to Baharampur Krishnanath College under this compulsion and enrolled in a BA course. But he did not hide the truth at the time of admission. After hearing his candid statement, the then principal of Baharampur College, Sasishekhar Banerjee, did not hesitate at all to admit him to the college. While signing the admission order, he said, ‘Go, study diligently’. On afterthought, it appears to be really good to come and join the K N College because Surya first got involved in revolutionary politics only after coming to Baharampur. Surya Sen entered politics with the inspiration of revolutionary Satish Chandra Chakraborty, a Jugantar party activist and one of the comrades of Baghajatin in the Indo-German armed resistance program. He got the real revolutionary education from Satish Chandra. Satish Chandra told him about the Easter Rebellion in Ireland. Thousands of freedom-loving Irish youths proudly declared, ‘Be it for the defence or be it for the assertion of a national liberty, I look upon the sword as a sacred weapon’. He also learnt about Baghajatin’s indomitable fighting spirit from Satishchandra. Baghajatin used to say: ‘None but the brave/None but the brave/None but the brave/Deserves the fair’. Young Surya Sen found a new way to live in Satishchandra’s eloquent speech – ‘Let the chain be broken, let new joy be built in new life’.

Surya Sen returned to Chittagong in 1918 after completing his college studies. He started working as a mathematics teacher at the local Umatara High School. But the thought of building a revolutionary organization in Chittagong began to wander in his mind all the time. Attempts were made to build a revolutionary organization in Chittagong quite some time ago. But they were not very effective. So, this time, Surya Sen, who came to be known as Masterda, jumped to build a strong organization that would be shaking the foundations of the British colonial rule in India shortly. Julu Sen, Nirmal Sen, Anurup Sen, Ambika Chakraborty, Charubikash Dutta and others came together with the determination to fight against the colonial rulers. In 1918, a new revolutionary organization was formed under the leadership of Masterda – a new campaign began. One by one, Anant Singh, Ganesh Ghosh, Loknath Bal and many other teenagers & youths joined; under Masterda’s skillful management, the romantic rebel young minds transformed themselves into worthy leaders of the struggle. Gradually the organization spread to various villages and towns of the Chittagong district. In continuation of this process, in 1920, Masterda built a temporary shelter — ‘Samyashram’ in Chittagong’s Dewan Bazar. Ashram in name only, it was actually a meeting place of revolutionary workers.

Responding to Gandhiji’s call, Masterda and his colleagues in 1921 joined the Non-Cooperation Movement, suspending all other programmes. But suddenly Gandhiji lifted the movement. After the withdrawal of the Non-Cooperation Movement, there was widespread frustration and anger across the country. The revolutionaries of Chittagong were not left out. But Masterda did not sit idle. He has only one thought, only one dream. ‘The object of the association is to establish a Federated Republic of the states of India by an organized and armed revolution’. The decision was taken to initiate an armed struggle; for this the revolutionaries required money and weapons. So, the plan of dacoity (robbery) was first taken to collect the money. The first plan could not raise the necessary funds. The second plan is more adventurous. On December 26, 1923, the Assam Bengal Railway was robbed of seventeen thousand rupees. But the police could find them shortly in the Sulukbahar hideout where the revolutionaries were hiding then. When the revolutionaries reached Nagarkana hill while escaping, they were surrounded by the police force. A gunfight ensued, But this unequal struggle did not last long. Masterda and Ambika Chakraborty became injured and captured. The rest managed to escape. Within a few days, Anant was also arrested. The trial began. Deshapriya Jatindramohan Sengupta, a son of Chittagong, pleaded for the revolutionaries in the trial and by his eloquence, logic and legal acumen brought them out of jail, defeating all the efforts of the government. The time was 1924.

But the police-administration did not stop chasing the revolutionaries. One by one the organizers and leaders — Ambika Chakraborty, Nirmal Sen, Anant Singh, Ganesh Ghosh, Anurup Sen etc. were arrested from the hideouts. Masterda first came to Calcutta to avoid arrest. But even there the police were behind him. Even in the early twenties the secret police note stated about Masterda: ‘An advocate of violence in its extreme forms and a notoriously dangerous leader of the terrorist parties…’. In the eyes of the police, Masterda was one such ‘terrible revolutionary leader’. Constantly shifting his abode, Masterda first went to Assam and later to the United Provinces to assist and oversee the works of revolutionary organizations there. He was again arrested by the police on October 8, 1926, when he returned to Calcutta after becoming acquainted with the revolutionary efforts of North India. Masterda was first kept in the Medinipur jail; then in Ratnagiri and Belgaon jails. Masterda was released from Belgaon jail on parole in 1928 because of his wife’s serious illness.

The jailed revolutionaries came back to Chittagong after being released and were united again. The revolutionary movement started with new enthusiasm. The successful implementation of the revolutionary planning had to be done very secretly; avoiding the attention of the police administration and leaving no room for treachery. Various gymnasiums were established in Sadarghat, Chandanpura and other villages to recruit students and youths for the revolutionary organization. In early 1929, Masterda was elected General Secretary of the Chittagong District Congress committee. Revolutionary workers also came to be known as Congress workers in the public eye. And the preparations for the final struggle continued under the guise of Congress workers. In 1929, the Indian Republican Army (IRA)- Chittagong branch was established. The commander-in-chief was Masterda Surya Sen; Ambika Chakraborty, Nirmal Sen, Anant Singh and Ganesh Ghosh were selected as members of the central committee. After a long discussion, the members of the IRA came to the conclusion that, rather than killing a few tyrannical colonial rulers, an armed revolt against the imperialist administration in at least one district, Chittagong, and if that district could be freed from imperial rule even for a few days, it would be an unprecedented event for the people of the whole country. This would encourage and motivate the people in fighting the colonial rulers more vigorously. The District Congress under the leadership of Masterda took up the program of defiance of the Salt Act from 21 April 1930. As a result of adopting this program, there was a relaxation in the police and intelligence department about the secret planning of the revolutionaries. With the announcement of this public program, the revolutionaries fixed the day of the youth uprising — 18 April 1930. The program of death has been accepted:

‘There is not to make reply,

There is not to reason why,

There is but to do and die’.

In order to make the youth rebellion successful, the revolutionary leaders adopted these programs — 1. occupying the police armoury; 2. taking possession of the armoury of the Auxiliary Force; 3. demolition of telephone and telegraph facilities; 4. European Club Attack; 5. cutting off railway communication between Chittagong and other parts of the country and, finally, 6. Disseminating news of rebellion. It was also planned that after the implementation of the above programs, the following would have to be implemented — 1. All gun shops and the government Imperial Bank in the city would be seized and the weapons and money be used in the revolutionary struggle. 2. The flag of the Indian Republican Army-Chittagong branch would be hoisted on Kachari Hill after occupying the city, establishing a democratic government and announcing the name of Masterda Surya Sen as the head of that government. At the same time, the English District Magistrate and other important public servants would be arrested and publicly tried. It was decided to distribute among the people the three manifestos signed by Masterda as the President of the Republic of India, Chittagong Branch, before the uprising. One was for the countrymen; another was for the people of Chittagong and the third was for the students and youth of Chittagong. In the manifesto, the revolutionaries emphatically said: ‘The Indian Republican Army, Chittagong Branch, hereby solemnly declare (that)…… the right of ownership and the control of her destinies belong to the people of India only and the long usurpation of that right by a foreign people and their Government has not extinguished that right nor it ever CAN. The Indian Republican Army proclaims today its intention of asserting this right in arms in the face of the world and thus put into actual practice the idea of Indian Independence declared by the Indian National Congress; and hereby pledges the life of every one of its members to the cause of freedom, to the welfare and exaltation of the motherland amongst all other nations’.

The members of the Indian Republican Army (Chittagong branch) dressed in full military uniforms according to their status proceeded to fight against the British forces. As the Chief of the Republic of India Army, Anant Sing reminiscences, ‘Masterda was attired in pure white dress with a stiffly ironed Gandhian Cap on his head-adorned with a shining metallic button embossed with Mother India’s symbol… Metallic insignia of the President of Indian Republic Army, Chittagong Branch, was affixed on the left breast of his long coat’. On April 18, the revolt started at 10 pm — 60-70 revolutionaries were actively involved in it. Some of the assigned activities of rebellion were successfully completed. The armoury was looted. Masterda ordered the ‘Union Jack’ to be set on fire, ‘Gun-salute’ was given. The revolutionaries chanted slogans — ‘Death to Imperialism’, ‘Long live the Revolution’ and ‘Bande Mataram’. The national flag of India was hoisted. Then Masterda announced in front of the assembled revolutionaries — ‘The enemy is defeated. The oppressive foreign rule has ended and the national flag is flying. Our duty is to protect the dignity of this flag even at the cost of our lives. As the Chief of the Indian Republican Army-Chittagong Branch, I hereby proclaim it to be the Free National Revolutionary Government… This Provisional Government expects that each young man and woman will swear allegiance and extend full support to it’.

Partial success has been achieved; but after the initial euphoria, it turned out that the European Club attack was not successful, as the club was closed that day for Good Friday. A bigger problem appeared in another case. Anant Singh wrote: Although they ‘could get hold of a large number of army vehicles and Luis Guns, they could not find a single bullet. This was a disastrous set-back in our plan and was the signal cause for the defeat of the military strategy of the revolutionaries. Had we got the ammunition for the four hundred rifles and seven Luis Guns the history of the Chittagong Uprising would have been a different one.’ The revolutionaries were, therefore, forced to withdraw their original plan! Two armouries were captured, telegraph and telephone lines were cut off, train communication was cut off in two places, leaflets were distributed urging the youth of Chittagong to join the rebellion! But how could they fight? All the guns were immobilized! Fighting with a few revolvers and musketries against the well-armed British forces means certain death! Masterda on hearing this, in the words of Anant Singh, became ‘pensive and brooding’.

Another big disaster happened in the action plan of the revolutionaries. When the weapons in the armoury became unusable due to lack of cartridges, it was decided to set them on fire. Himanshu Sen sustained severe burn injury while setting the fire; One of the two main commanders of the revolutionary forces — Anant Singh and Ganesh Ghosh — left for the city with a car to save him. Jiban Ghoshal and Anand Gupta also went along with them. Without taking the permission of the Commander-in-Chief, they went towards the city. But even after waiting for long, Anant and Ganesh could not come and join the rest of the revolutionaries. All plans had to be changed. Attacking the city, seizing the Imperial Bank, seizing the prison and freeing the prisoners — all had to be cancelled. The revolutionaries thought of taking refuge in the nearby hilly areas. As everything did not go according to plan, they also lacked food and water. They were forced to consume green mangoes and tamarind leaves to quench their thirst and appetite. In this situation, the revolutionaries wanted to remain in hiding no longer and return to the city, where they would face the British forces, albeit unequally. That time they took shelter in Jalalabad hill. That day was April 22. Three days have passed since the youth uprising. They waited for the darkness of the night — to start the journey towards the city.

But in the meantime, the British forces found out that the revolutionaries had taken refuge in the Jalalabad hills. British troops arrived by train. The revolutionaries understood that now they would have to give the test of their revolutionary determination. The fight began. The fight lasted for over two hours. The objective of the British police and paramilitary was to force the surrender or exterminate the revolutionaries. But the attempt of the British forces failed miserably. The revolutionaries won the battle of Jalalabad. The British forces retreated back to the barracks. Kalpana Dutta wrote: ‘It was not possible to know the exact number of dead and wounded on the government side in this war. Rumours abound in the city — some say 150, some say government soldiers who went did not return. … … Two months later when Ganesh Ghosh and others were caught in Chandannagar, Charles Tegart said while beating them – you have finished 64 of us.’

And among the revolutionaries, eleven died as martyrs in Jalalabad. They were: Harigopal Baul (16), Nirmal Lala (14), Tripura Sen (16), Bidhubhushan Bhattacharya (20), Prabhas Baul (18), Shashank Dutta (18), Madhusudan Dutta (26), Naresh Roy (20), Pulin Ghosh (19), Moti Kanungo (19), Jitendra Dasgupta (20). Four people were injured: Ambika Chakraborty (34), Ardhendu Dastidar (19), Binod Dutta (18), Binod Chowdhury (19). Among them, Ardhendu, who was seriously injured, died as a martyr in Chittagong Hospital the next day. These revolutionaries who gave up their lives prematurely as martyrs so much mesmerised the people of India with their heroic fights that the people of Bengal started lovingly calling them ‘Flowers of Bengal’. Masterda and his revolutionary army came down from the hill after paying their last respect to the martyred revolutionary comrades. Those among the Jalalabad warriors who were unknown to the police were asked to return home; told to wait for next time. And the rest of the revolutionaries led by Masterda went out in search of some other safe haven.

The Chittagong Youth Rebellion of April 18 and the Jalalabad Hill Battle on April 22 are unique achievements in the history of the revolutionary nationalist movement in India. The newspaper, Swadhinata, in an article saluting the struggle of the Chittagong revolutionaries under the leadership of Masterda wrote: ‘The beginning of the ideal of the revolution — ‘attack, attack, plunder and possess multiple centres of foreign rulers at the same time by blocking the enemy’s travel and communication in one city, one or five districts — debuted in Chittagong’. The ultimate manifestation of the revolutionary nationalist movement in the country was seen through the Chittagong Youth Rebellion.

The Chittagong revolutionaries led by Masterda played this unique role in many areas. Firstly, for the first time in a district town, the revolutionaries were able to paralyze the entire British administration for three days. Fearing the revolutionaries, British bureaucrats and employees left their official residence for three days and spent the night with their families on steamers adjacent to the Chittagong port.

Secondly, this was the first time that the brave revolutionaries had won a face-to-face gunfight against the British army; The armed British forces, despite having advanced weapons, were defeated in the Jalalabad hill battle and forced to retreat.

Thirdly, the brave soldiers of the Indian Republican Army-Chittagong branch did not just cling to one of the tactics of revolutionary nationalism, ‘Hit & Run’. Knowing that they would die, they fought in groups directly facing the foreign forces; They had the plan to enter Chittagong city with weapons as well. Never before in the history of revolutionary movements has a group fight so crazy in self-sacrifice been seen. All that had gone before had been largely plans of individual assassination, but as a collective struggle, the revolutionaries of Chittagong were the first and the last. After April 18 and 22, the Writers’ attack of Binay-Badal-Dinesh in Calcutta on December 8, 1930 and the gunfight seemed to be a miniature version of the Chittagong Youth Rebellion.

Fourthly, in all the revolutionary groups’ everyone had to follow certain Hindu religious rules while taking the oath as a revolutionary. That is why in the history of the revolutionary movement, Muslim activists have not been seen much. The only exception was the Masterda’s IRA. At that time, the discussion of creating a revolutionary organization was going on. After the adoption of the constitution, the discussion was about the oath-taking ceremony of the workers. Oath by touching the Gita, giving blood to Mother Kali by slitting the chest — all these proposals came up one by one. But Masterda and many others, especially the young revolutionary Anurup Chandra Sen (expired in 1928 while interned in Kashi), felt that there was really no need to observe special religious ceremonies. Was this not unnecessary? Because all other organizations follow this practice, do they have to adopt it? In the end, everyone decided to boycott the religious ceremony. They no longer felt the need to take formal oaths on religious lines. How much of this non-communal face of Masterda and his organization spread in the Muslim-dominated villages of Chittagong is evidenced by the fact that two years and nine months and twenty-eight days after the armoury raid, Masterda continued his struggle keeping himself in the underground despite extremely adverse conditions. Kalpana Dutta wrote: ‘During the anti-Japan campaign in Gairla village where Masterda was caught, one of the Muslim villagers said — Shall we go for the Japanese like the Dendas (Muslims call Hindus derisively Denda in Chittagong)? It was Dendas who helped the British in arresting Surya Sen.’ The Muslim villagers were angry with the Hindus as one of them betrayed Masterda! Where else can we find such examples?

Fifthly, the revolutionaries of Chittagong took another unprecedented step under the leadership of Masterda. The initial policy of the group was to stay away from contact with girls. But in the post-armoury-looting period, Masterda recruited Kalpana Dutta and Pritilata Waddadar. He did not stop by only including them in the party but also ordered them to go into fugitive life for the sake of the revolutionary movement. Seeing the courage and dedication of Kalpana and Priti, Masterda gave them revolutionary responsibilities. Priti was the headmistress of Nandankanan Aparna Charan High School for Girls. But she wanted to take a direct role in revolutionary action. Finally, with Masterda’s permission, on September 24, 1932, seven youths led by Pritilalta attacked the European Club in Pahartali in the dark of night. The campaign was successful. At the end of the campaign, everyone left; But Priti stayed back. It was necessary to prove to the countrymen that women can directly participate in revolutionary activities and give their lives. So, Priti (Masterda’s ‘Rani’) committed suicide by consuming potassium cyanide. The first and only female martyr of colonial India. This self-sacrifice of Pritilata, the uncompromising fight of Kalpana gave the girls of the country the motivation to join the revolutionary movement. Here too Masterda and his organization remained pioneers in the revolutionary movement.

Masterda was arrested by the police on 16 February 1933. Tarakeswar Dastidar and Kalpana were arrested on May 19. All active revolutionary workers were apprehended one by one. Earlier on August 4, 1931, another Chittagong martyr Ramakrishna Biswas (stood first in Chittagong district in 1928 matric examination) gave up his life in the gallows in Alipore Central Jail. Along with Kalipada Chakraborty, Ramakrishna was caught trying to kill IG Craig of the Bengal Police. Ramakrishna was very close to Pritilata; his self-sacrifice greatly inspired Pritilata; in tune with the great revolutionary tradition, Pritilata also laid down her life in the following year. Masterda’s trial began in June 1933. The farce of trial continued in the Special Tribunal. Masterda and Tarakeshwar were ordered to be hanged till death; A lifetime sentence for Kalpana. The day of execution of Masterda and Tarakeshwar was fixed on January 12, 1934. Before that, however, Masterda came to know that the traitor Netra Sen, who betrayed him, was beheaded by his revolutionary compatriots (January 2, 1934). The executions of Masterda and Tarakeshwar exposed the real character of British culture and civilisation. They were tortured and hanged from the gallows in an unconscious state. Their bodies were not handed over to their relatives. Defying all norms of civilized society, the bodies of Masterda and Tarakeshwar were loaded into a large iron trunk and thrown into the Bay of Bengal. The aim was that no one can pay respect to their beloved leader. Colonial rulers were so afraid of Masterda alive or dead! The struggle of the brave revolutionaries of Chittagong ended here, but left behind the exemplary education of revolutionary life and struggle — discipline, self-sacrifice, fearless struggle, brotherhood and how to overcome fear. All the revolutionaries who were imprisoned in the mainland or in the Andamans were released in 1937-38 or 1946. They did not go back to the old ways of armed struggle. Some embraced Marxism, some joined the Indian National Congress or the Forward Bloc. The great revolutionary activities of the Indian Republican Army- Chittagong branch came to an end.

At seven in the evening on the day before he was hanged, Masterda wrote his FINAL farewell message:

Ideal and Unity is my farewell message. Rope is hanging over my head. Death is knocking at my door. Mind is soaring towards eternity. This is the time for ‘Sadhana’, this is the time for preparation to embrace death as a friend and this is the time to recall lights of other days as well.

Sweet remembrance of you all, my dear brothers and sisters, break the monotony of my life and cheer me up. At such a pleasant, at such a grave, at such a solemn moment, what shall I leave behind for you? Only one thing, that is my dream, a golden dream — a dream of free India. How auspicious a moment it was, when I first saw it. Throughout my life most passionately and untiringly I have pursued it like a lunatic. I know not how far I proceeded towards the fulfilment of my dream. I know not where I am compelled to stop my pursuit today. If icy hands of death give you a touch before the goal is reached, then give the charge of your further pursuit to your followers as I do today. Onward my comrades, onward — never fall back. The day of bondage is disappearing and the dawn of freedom is ushered in. Be up and doing. Never be disappointed. Success sure. God bless you.

Never forget the 18th April, 1930, the day of Eastern Rebellion in Chittagong. Keep ever fresh in your memory the fights of Jalalabad, Julda, Chandernagar and Dhalghat. Write in red letters in the core of your hearts the names of all patriots who have sacrificed their lives at the altar of India’s freedom.

My earnest appeal to you — there would be no division in our organization. My blessings to you all inside and outside the jail.

Fare you well

Long live Revolution!

Banda Mataram!

Now is the time to enrich ourselves again with the education of those brave revolutionaries. The country is far away from the ideas of non-communal secular republican democratic India that they dreamt of. All shades of democratic rights, freedom of expression are being taken away today. At this time, it is the responsibility of the present generation to carry on the legacy of the revolutionary tradition of Masterda and his fellow comrades. In the struggle to fulfil the unfulfilled dreams, let the lessons be learnt from the supreme sacrifices of the leaders like Masterda and the thousands of revolutionaries!

References–

Banerjee Deb, Swati & Deb, Bikash Ranjan (December, 2022). National Revolutionism in Colonial Bengal: A Re-look at a Neglected History in Das, Asit, (ed). International Journal of Research (IISRR)-8; Issue-II, Online Version ISSN 2394-885X, IISRR-IJR, Kolkata.

Dasgupta, Tushar Kanti and Sen, Dilip Kumar (1974). Biplabi Mahanayak Surya Sen (Revolutionary Hero Surya Sen). Barasat: Shri Swapan Kumar Sen.

Dutta, Kalpana (1946). Chattagram Astragar Lunthankarider Smritikatha (Memoirs of Chittagong Armoury Raiders). Third Radical Edition, 2020. Calcutta: Radical Impressions.

Ghosh Shankar (2012). Masterda Surya Sen. Calcutta: Prometheus.

Halder, Gopal (2002). ‘Revolutionary Terrorism’ in Gupta, AC (ed), Studies in Bengal Renaissance-Third Revised Edition. Kolkata: National Council of Education.

Laushey, David M (1975). Bengal Terrorism and Marxist Left-Aspects of Regional Nationalism in India, 1905-1942. Calcutta: Firma KLM.

Majumder, Subhendu (2022). Agniyuger Abhidhan (Dictionary of the Age of Fire). Calcutta: Radical Impressions.

Pakrashi, Satish (2015). Agniyuger Katha (About the Age of Fire). Calcutta: Radical Impressions.

Pramanik, Nimai (1984). Gandhi and the Indian National Revolutionaries. Calcutta: Sribhumi.

Ray, Nisith Ranjan et al (eds) (1984). Challenge- a Saga of India’s Struggle for Freedom. New Delhi: PPH/ Chittagong Uprising Golden Jubilee Committee.

(The author is Professor, Political Science, Surya Sen Mahavidyalaya, Siliguri)

Thanks for publishing the article. Im the author of this essay. However, I have been teaching Political Science in Surya Sen Mahavidyalaya, Siliguri and not in Siliguri College as mentioned here. I would be immensely benefitted if you kindly rectify my actual place of work.