The task of today’s transnational popular front against plutofascism is to create “new modes of friendship, happiness, and solidarity”. This means giving every polity, language and community on the planet the tools to engage with and learn from every other polity, language and community. It also means a radical politics of memory which is rooted not just in the commemoration of the radical achievements of the past, but also in the active reconstruction of a future for all 8 billion human beings on this planet. We are all in the same boat – a small, crowded planet floating in an inconceivably vast galaxy – and we must learn to sail together. An article by Dennis Redmond.

The single biggest political story of the 2020s is the contest between the democracy of the 8 billion of us who live on this planet, and the despotism of the 3,000 billionaires who exploit us. The most striking expression of this democracy is an emergent alliance of independent journalists, service-sector unions, anti-monopoly activists and ordinary citizens, which is facing off against the combined forces of plutocracy and plutofascism.

The single greatest challenge facing this democratic alliance is the fact that our planet is divided into two hundred distinct polities, hundreds of separate languages, and thousands of distinct ethnic, linguistic, confessional and occupational communities. Whereas the plutocrats and plutofascists have a clear sense of what they want – namely, to grab more wealth and power for themselves while immiserating or exterminating everyone else – we billions of commoners have only just begun to create the pro-democracy and anti-fascist alliances we need to save our planet from destruction.

To answer this challenge, it is worth reflecting on the lessons from the last time humanity had to organize a planetary movement to save the world from fascism, namely the Popular Front of 1940-1945. The progressive artists of the Front produced an astonishing bevy of works ranging from films such as Charlie Chaplin’s The Great Dictator (1940) and prose works such as Langston Hughes’ autobiographical The Big Sea (1940) to plays such as Bertolt Brecht’s The Good Person of Szechwan (1941), Jean-Paul Sartre’s No Exit (1944) and Bijon Battacharya’s Nabanna [New Harvest] (1944). These works successfully appealed to audiences divided by some of the most violent forms of racism, misogyny, xenophobia, sectarianism, homophobia and casteism in human history, and remain models of anti-fascist and pro-democracy art to this day.

Yet one of the most astonishing success stories of the original Popular Front is also one of the least appreciated today. This was its creation of the basic template of post-1945 transnational popular music. This template was the three to four minute musical work which combined the rhythmic innovations of international jazz modernism,1 the lyrical innovations of US blues and gospel music, and the acoustic innovations of the European atonal composers.2 Whereas all previous forms of music were designed primarily as live performances, this new template was capable of switching seamlessly between the live venue (the stage performance or radio broadcast) as well as the recorded phonograph and the cinema soundtrack.

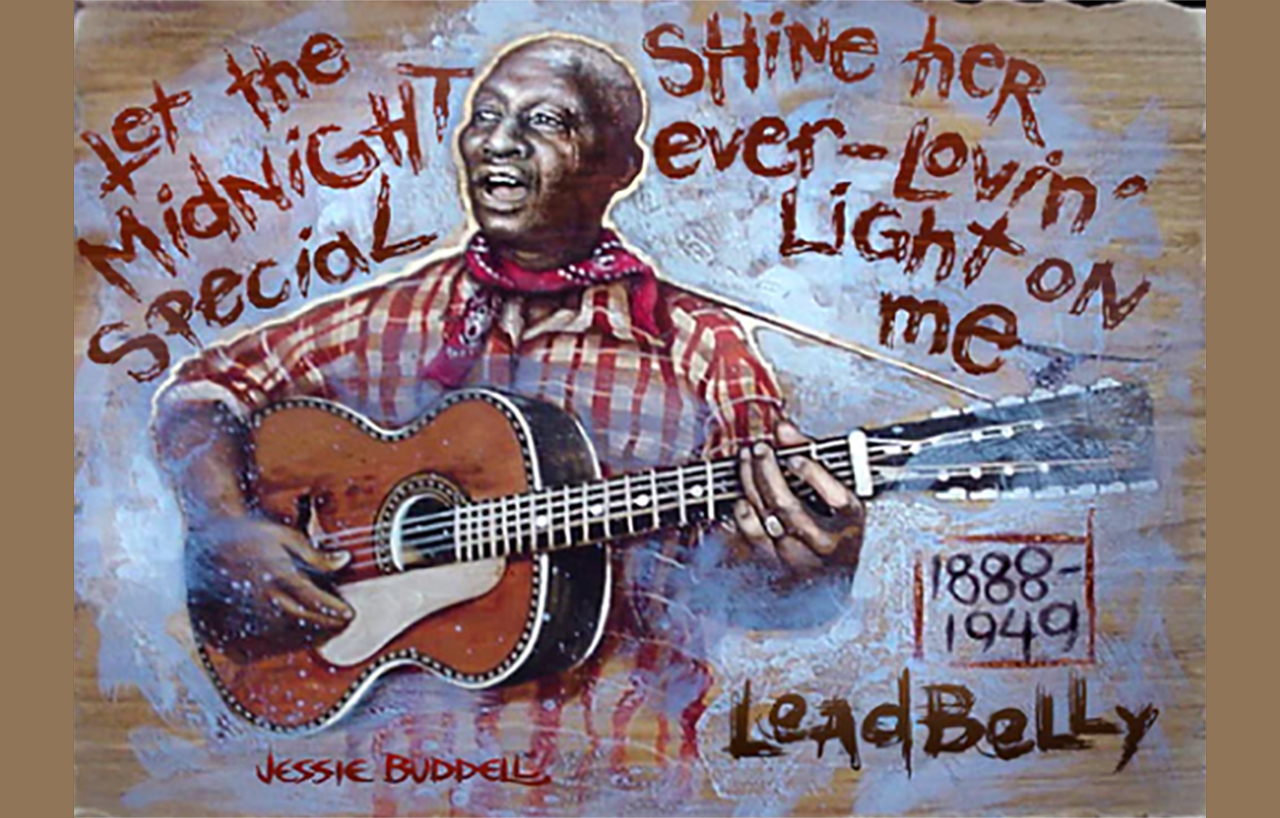

Our main example of this template will be US blues singer Lead Belly’s 1948 rendition of We’re in the Same Boat, Brother (hereafter referred to as Same Boat), a song originally written in 1944 by lyricist Yip Harburg and tunesmith Early Robinson. In our own time, Lead Belly is most famous for his classic rendition of Pick a Bale of Cotton, Harburg for writing the stinging lyrics for the Depression-era hit song Brother, Can You Spare a Dime? (1932), and Robinson for composing the classic progressive song I Dreamed I Saw Joe Hill Last Night (1936).3

What made Same Boat a landmark work of transnational music was the fact that each of these artists united to create a whole greater than the sum of its parts. Robinson’s music borrowed from the call-and-response structure of early 20th century African American gospel music, wherein a solo voice elicited an answering chorus.4 Similarly, Harburg’s lyrics employed the African American musical form of the blues couplet. Last but not least, Lead Belly’s delivery utilized the techniques of African American talking blues and orature.

Together, they created a template which anticipated every major branch of late 20th century transnational popular music, from rock ‘n roll and rhythm-and-blues to Afrobeat and hip hop. Variations of this template can be heard to this day in the background music of every contemporary coffee-shop and mall, in the soundtracks of countless videogames, and in the streaming media played on billions of smartphones.

Before analyzing Same Boat in greater detail, however, it is worth answering three questions readers may have concerning this template. First, how was it possible for the US musicians of the Popular Front to be eighty years ahead of their time? Second, why did US musicians play such a crucial role in creating this template, as opposed to those of colonized Africa and Asia, Britain, Brazil, China, France, Germany, the Soviet Union or other polities of the 1940s? Third, why should progressives pay attention to transnational popular music anyway, given that most of it is commercial junk designed to sell things?

All three questions have a single answer. Same Boat was eighty years ahead of its time for the same reason that mid-20th century US popular culture became the template of late 20th century planetary popular culture, and the same reason progressives should critique transnational popular music rather than simply dismissing such.

The reason is that Karl Marx was correct. One of Marx’s most profound insights was that capitalism is a mode of production which by its very nature must spread the commodity form across the entire planet, and that it is only after this expansion is complete that humanity could begin to imagine what a truly humane society might look like.

It is easy to forget that when Marx passed away in 1883, the commodification of the planet had only just begun. In 1914, only one-third of the planet’s 1.7 billion inhabitants consisted of fully and partly waged workers, whereas two-thirds were subsistence farmers and craft workers who existed in conditions of feudalism, pastoralism and other precapitalist modes of production. As late as 1945, the planetary ratio was about 40% wage workers to 60% subsistence farmers.

Between 1945 and 2008, the sixty-three year period of history when the United States was the hegemonic polity of the world-system, the planetary ratio changed to 90% wage workers and 10% subsistence farmers.5 Paradoxical as it sounds, the United States was the single most successful (albeit unwitting) agent of proletarianization in world history.

The musical template produced by the Popular Front artists of the United States during 1940-1945 anticipated eight decades of transnational music to come for the simple reason that it took eighty years for the industrialization of the planet to catch up to the industrialization of the US in 1945.

In terms of economic and sociological metrics, the US in 1945 was 60% urbanized and had an automobile ownership rate of 221 per 1,000 people. Its population of 140 million had a life expectancy of 67, a fertility rate of 2.4, and 16% of all its workers were employed in agriculture.6 By comparison, the world today is 58% urbanized and has an automobile ownership rate of 181 per 1,000 people. The planetary population of 8 billion has a life expectancy of 73, a fertility rate of 2.4, and 25% of all workers are employed in agriculture.

Politically, the United States in 1945 was a limited democracy blighted by national plutocrats, violent forms of internal neocolonialism, and explosive regional inequalities. Even at the height of Roosevelt’s reformist New Deal, only 85% of all adults had the right to vote or basic civil rights, due to the system of open racial apartheid (so-called Jim Crow) which ruled about one-quarter of the United States between 1878 and 1965. This is directly comparable to today’s world, wherein two-thirds of all human beings live in electoral democracies disfigured by transnational plutocrats, violent forms of internal neocolonialism, and explosive regional inequalities.

The parallels extend to the cultural field. In 1945, the citizens of the US were 90% literate, had access to the most sophisticated media culture on the planet, and could dream of purchasing the world’s most advanced consumer goods (automobiles, refrigerators and radios). Today, the citizens of the planet are 90% literate, have access to the most advanced digital media on the planet thanks to billions of smartphones, and dream of purchasing transnational consumer goods.

With this comparative history in mind, we are now in a position to examine Same Boat more closely. Robinson’s citation of African American gospel music must be understood in the context of the centuries-old liberation struggle of the wageless laborers of North America, South America and West Asia. Since most African American slaves were not permitted to read or write but were allowed to have their own churches, they employed preaching as a means of covert educational mobilization (because preachers had to be able to read the Bible) and gospel music as a means of covert cultural identification.

Both preaching and gospel music employed call-and-response techniques, wherein the preacher would recite a line and the audience would shout out a confirmation, or where a lead singer would sing a line and a chorus would respond with a chorale. This call-and-response tradition would inspire generations of African American singers and musicians, in much the same way that the tradition of African American preaching inspired generations of civil rights activists and progressive politicians.7

After the US abolition of slavery in 1865, southern African Americans were transformed from wageless laborers into a partly waged workforce of sharecroppers and heavily indebted subsistence farmers. These sharecroppers and farmers were the main audience of the blues, a musical form which emerged throughout the US rural south at approximately the same moment that jazz began to emerge in US cities, namely after 1910.8 Blues musicians rewrote the liturgical texts and call-and-response structure of gospel music into a form featuring plebian lyrics and a signature instrumental riff or guitar solo. This solo was created by bending the guitar strings or sliding along the guitar neck, creating a vibrating, quavering effect which enabled a single performer to generate a wide variety of tones and pitches.

One of the most famous post-emancipation rural sharecroppers who became a blues musician was Lead Belly, the stage name of Huddie William Ledbetter (1888-1949). He was born to a family of sharecroppers in the tiny hamlet of Mooringsport, Louisiana, 29 kilometers from the city of Shreveport, and became an itinerant musician at the age of fifteen. Like tens of thousands of other African Americans, Lead Belly was imprisoned a number of times between 1915 and 1939.

It was during one of these sojourns in prison that he garnered the attention of the father and son duo of John and Neil Lomax, who were collecting American folk songs on behalf of US President Franklin Roosevelt’s New Deal. The Lomaxes discovered Lead Belly during a visit to a Louisiana prison in 1932 or 1933, and arranged for the 1933 and 1934 recording sessions which launched his musical career. Lead Belly endowed each line of Harburg’s text with the vocal energy of an African American preacher, the acoustic energy of the blues performer, and the rhythmic energy of the jazz soloist:

[Chorus]: We’re in the same boat, brother

We’re in the same boat, brother

And if you shake one end

You’re gonna rock the other

It’s the same boat, brother

[First verse]:

Oh the Lord looked down from his holy place

Said, ‘Lordy me, what a sea of space

What a spot to launch the human race.’

So he built him a boat for a mixed up crew

With eyes of black and brown and blue

So that’s how come that you and I

Got just one world with just one sky

Harburg’s first verse did two things no other work of popular American music had achieved before. First, it rewrote the 19th century trope of the ocean voyage with the 20th century trope of space travel, i.e. the space of the sea has become the “sea of space”. Second, the verse rewrote the Biblical parable of Noah’s ark, the mythical craft which saved humanity from a world-ending flood, into a parable of the Allied naval mobilization of World War II.

This mobilization ferried a multiracial army (“eyes of black and brown and blue”) across the world’s oceans and onto the contested beaches of northern Africa, western Europe and the Pacific theater. One of its most famous manifestations was the shallow draught Higgins landing craft. A total of 20,094 Higgins boats were produced during the war, and played an indispensable role in every single Allied amphibious landing between 1942 and 1945.9 This massive armada was produced by a multiracial, gender-diverse, and unionized workforce located primarily in New Orleans (the American Federation of Labor won bargaining rights at Higgins’ factory in 1940).10

The second verse expanded on the theme of wartime solidarity with three additional references to the African American liberation struggle:

[Second verse]:

Oh the boat rolled on through storm and grief

Past many a rock and many a reef

What kept ’em goin’ was a great belief

So they had to learn to navigate

’Cause the human race was special freight

If we didn’t want to be in Jonah’s shoes

We’d better be mates on this here cruise

The first reference was to the Biblical tale of Jonah’s rescue after being swallowed by a whale. This is a story of captivity and deliverance which is one of the oldest tropes of abolitionism in the annals of the African American liberation struggle. The second reference was to the notion of human beings as freight. This referred to the slave ships which carried somewhere between 7 to 10 million African captives between the 1550s and 1865.11 The third reference was a direct appeal to wartime solidarity (“We’d better be mates on this here cruise”). This anticipated US President Truman’s 1948 executive order to desegregate all branches of the US armed forces, as well as the transformation of the US civil rights struggle into a mass movement thanks to the participation of African American veterans of World War II.

The third and final verse delivered an extraordinarily subtle analysis of late 19th and early 20th century imperialism and anti-colonial resistance:

[Third verse]:

When the boilers blew somewhere in Spain

The keel was smashed in the far Ukraine

And the steam poured out from Oregon to Maine

Oh it took some time for the crew to learn

What’s bad for the bow ain’t good for the stern

If a hatch takes fire in China Bay

Pearl Harbor’s decks gonna blaze away

The first line alluded to the 19th century literary trope of the steamship boiler explosion as well as the catastrophic victory of Franco’s fascist army over Spain’s democracy during the late 1930s. Similarly, the reference to Ukraine referred to the bloody battles of 1942 and 1943 between the Soviet Red Army and the Nazi German army in the Ukrainian province of Crimea, but it was also a nod towards the Romanov dynasty’s late 19th century attempt to seize the Turkish straits from the Ottoman empire – the maritime adventurism which co-triggered World War I along with Austria-Hungary’s declaration of war on Serbia.12

The third line referred to the US warships Maine and Oregon, while the fourth and fifth lines made reference to the harsh lessons of neocolonial and colonial history (“Oh it took some time for the crew to learn / What’s bad for the bow ain’t good for the stern”).

The Maine exploded in the harbor of Havana in Spanish-controlled Cuba on February 15, 1898, in what was almost surely an accident (coal-fired steam engines were prone to such explosions). However, the plutocrat-owned mainstream media of the United States successfully whipped up war hysteria against the Spanish empire. This hysteria was facilitated by the fact that Spain had been committing genocidal atrocities against ongoing insurgencies in its Cuban and the Philippine colonies.13

US imperial elites subsequently declared war on Spain, destroyed its navy (the Oregon was one of the US vessels deployed in these battles) and seized most of Spain’s colonies. The nominal reason for this war was to support Cuba’s independence, but the real motivation was to create a US maritime empire in the Caribbean and Pacific comparable to that of Britain, France, Japan and the Netherlands.14

The plan failed in Cuba thanks to the resistance of ordinary Cubans, who rejected US annexation and won a degree of political independence as early as 1902.15 The plan also failed in the Philippines, where the US occupation triggered a massive anti-US insurgency. This insurgency was temporarily quelled by the deployment of 125,000 US soldiers, the expenditure of $400 million (a colossal sum at the time), and a grinding three-year military campaign which caused the deaths of about 4,000 US soldiers, 16,000 insurgents, and somewhere between 200,000 to 500,000 civilians (3% to 6% of the pre-war population of the Philippines).16

However, pockets of guerrilla resistance continued deep in the rural interior, and later generations of Filipinos would continue the struggle for national independence with electoral means. Thanks to intensive lobbying by Filipinos and progressive US citizens, the US Congress passed the Jones Act in 1916 which promised the Philippines independence, although without a specific date. The US finally agreed in 1935 to set the date of independence in 1945, a timeline derailed by the 1941-1945 invasion and occupation of the Philippines by imperial Japan. The invasion triggered a massive uprising by Filipinos, a quarter of a million of whom participated in a ferocious guerrilla war against the occupiers. This long history of struggle culminated in the Philippines’ official independence in 1946.17

The sixth line of Same Boat’s third verse referred to the December 7, 1941 attack by imperial Japan on the US navy’s main base in Hawaii, which triggered the full-scale US entrance into World War II. The seventh line could either be a reference to the full-scale Japanese invasion of mainland China in 1937 (Japan had previously occupied China’s provinces of Taiwan and Manchuria), or else a reference to China Bay Airport. This latter was a British airfield located on the eastern coast of Sri Lanka close to the city of Trincomalee, which served as the staging-point for a squadron of US B-29 bombers during 1944 and 1945.

Putting all the pieces together, Lead Belly, Harburg and Robinson created a classic which was simultaneously an anthem of interracial democracy, an ode to international solidarity, and an anti-colonial history lesson. The song exemplified what Paul Gilroy’s The Black Atlantic (1993) called the politics of transfiguration characteristic of African American popular music. It is no accident that Gilroy linked this transfiguration to Theodor Adorno’s concept of radical aesthetics, which was deeply rooted in a musicological analysis of the European atonal composers of the early 20th century. Adorno described the radical potential of this music not in terms of its capacity to evoke memories of the past, but a memory of the future:

The wilfully damaged signs which betray the resolutely utopian politics of transfiguration therefore partially transcend modernity, constructing both an imaginary anti-modern past and a postmodern yet-to-come. This is not a counter-discourse but a counterculture that defiantly reconstructs its own critical, intellectual, and moral genealogy in a partially hidden public sphere of its own. The politics of transfiguration therefore reveals the hidden internal fissures in the concept of modernity. The bounds of politics are extended precisely because this tradition of expression refuses to accept that the political is a readily separable domain. Its basic desire is to conjure up and enact the new modes of friendship, happiness, and solidarity that are consequent on the overcoming of the racial oppression on which modernity and its antinomy of rational, western progress as excessive barbarity relied. Thus the vernacular arts of the children of slaves give rise to a verdict on the role of art which is strikingly in harmony with [Theodor] Adorno’s reflections on the dynamics of European artistic expression in the wake of Auschwitz: ‘Because the utopia of art, of that which is not yet existent [Seiende: everyday existence or presence], is draped in black, it thus remains throughout all its mediations a memory – that of the possible against that which is actual, which this latter suppresses; as freedom, as something like the imaginary redemption of the catastrophe of world history, which has not yet been realized under the baleful spell of necessity, and it remains uncertain as to whether it will do so.’18

Conversely, the task of today’s transnational popular front against plutofascism is to create Gilroy’s “new modes of friendship, happiness, and solidarity”. This means giving every polity, language and community on the planet the tools to engage with and learn from every other polity, language and community. It also means a radical politics of memory which is rooted not just in the commemoration of the radical achievements of the past, but also in the active reconstruction of a future for all 8 billion human beings on this planet. We are all in the same boat – a small, crowded planet floating in an inconceivably vast galaxy – and we must learn to sail together.

Footnotes

1 We define jazz modernism as the international art-form based on a blend of metrical (i.e. European) and additive (Western African) rhythmic structures which flourished between 1914 and 1965. Its most famous composers included Charles Ives, Louis Armstrong, Count Basie, Charlie Parker and John Coltrane. While most of the major composers of jazz modernism were American, the art-form was inherently international and comprised innumerable non-US singers and performers.

2 The three leading composers of European atonality or twelve-tone music were Anton Webern, Alban Berg and Arnold Schönberg.

3 Jay Gorney wrote the music to Brother, Can You Spare a Dime?, while Alfred Hayes wrote the poem Joe Hill which Earl Robinson put into music.

4 Earl Robinson performed the gospel version of Same Boat here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=JrbmA31BoSA.

5 Here in 2022, the ratio is approximately 95% wage workers and 5% subsistence farmers.

6 This is data from the US Census Bureau. https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/1949/compendia/hist_stats_1789-1945/hist_stats_1789-1945-chD.pdf.

7 The latest iteration of this long-running tradition was Reverend Ralph Warnock’s 2022 election victory in the Senate elections in the US state of Georgia, the result of a long-term community mobilization by citizens under the age of twenty-five, by African Americans, and by progressive and pro-democracy white citizens of Georgia.

8 From a sociological point of view, the blues and jazz were the leading musical expressions of the 20th century migration of southern African Americans to the industrial cities of the midwest and north. While the blues began in the rural south and followed this migration to the urbanized north, jazz began in northern cities and traveled via live performances and recordings to the rural south.

9 “[Andrew] Higgins designed and produced two basic classes of military craft. The first class consisted of high-speed PT boats, which carried antiaircraft machine guns, smoke-screen devices, depth charges, and Higgins-designed compressed-air-fired torpedo tubes. Also in this class were the antisubmarine boats, dispatch boats, 170-foot freight supply vessels, and other specialized patrol craft produced for the army, navy, and Maritime Commission. The second class consisted of various types of Higgins landing craft (LCPs, LCPLs, LCVPs, LCMs) constructed of wood and steel that were used in transporting fully armed troops, light tanks, field artillery, and other mechanized equipment and supplies essential to amphibious operations. It was these boats that made D-Day and the landings at Guadalcanal, Iwo Jima, Tarawa, Okinawa, Leyte, Guam, and thousands of lesser-known assaults possible.

At the peak of production, the combined output of his plants exceeded 700 boats a month. His total output for the Allies during World War II was 20,094 boats, a production record for which Higgins Industries several times received the Army-Navy ‘E,’ the highest award that the armed forces could bestow upon a company.” Jerry E. Strahan. Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1994 (1-2).

10 “With the war draining the labor pool, he [Higgins] staffed his plants with a diversity of employees: healthy males who had not yet been drafted, women, blacks, elderly, and handicapped. Regardless of race, sex, age, or physical disability, all were paid equal wages according to their job rating. They responded by shattering production records.” Jerry E. Strahan, Andrew Jackson Higgins and the Boats That Won World War II (2).

11 While chattel slavery was a Pacific as well as an Atlantic phenomenon, the overwhelming majority of captives were transported from locations on the west African coast to plantations and mines in the Americas. Out of the estimated 12 million human beings subjected to chattel slavery, an estimated 6 million were killed during the initial slave raid or perished from disease, starvation or maltreatment in holding pens or while aboard slave ships. Slavery was the capitalist world-system’s first planetary genocide.

12 Prior to 1914, the Romanov empire was the largest debtor polity on earth, and paid for the French and British loans it needed to finance its economy by exporting Ukrainian grain via the Turkish straits. When the Ottoman empire tried to purchase battleships capable of choking off the straits, the Romanovs embarked on a policy of anti-Ottoman adventurism. This policy involved supporting the Serbian militia which assassinated Archduke Ferdinand. For further details of this history, see: Sean McMeekins. The Russian Origins of the First World War. Harvard: Belknap Press, 2011.

13 “For a week, the New York Journal devoted an average of eight and a half pages of news, editorials and pictures to the Maine. The editors mobilized a crack team of reporters and artists, including Frederic Remington, and dispatched them to Havana in the paper’s own press boats. William Randolph Hearst offered a fifty-thousand-dollar reward ‘for the conviction of the criminals who sent 258 American sailors to their death.’

Hearst veritably wallowed in lying sensationalism. The Journal for February 17 had no doubt whatever: ‘THE WARSHIP Maine WAS SPLIT IN TWO BY AN ENEMY’S SECRET INFERNAL MACHINE’; and ‘Captain Sigsbee practically declares that his ship was blown up by a mine or torpedo.’ An accompanying illustration, highlighted with a Maltese cross below the ship’s waterline, ‘shows where the mine may have been fired.’ ‘THE WHOLE COUNTRY THRILLS WITH WAR FEVER’, screamed the headline on February 18; ‘REMEMBER THE Maine! TO HELL WITH SPAIN!’” Ivan Musicant. Empire by Default: The Spanish-American War and the Dawn of the American Century. New York: Henry Holt, 1998 (143-144).

14 The US maritime expansionism of 1898 had two other key components which should be mentioned here: the opportunistic US annexation of Hawaii by English-speaking settler colonists, an event planned for 1897 but not officially carried out 1898, and the US-financed construction of the Panama canal after 1903 (this latter involved the creation of Panama, previously a province of Colombia, in 1904).

15 Cubans also resisted repeated US military interventions in 1906-1909, 1912 and 1917-1922.

16 It should be emphasized that Spain and the United States were not uniquely awful as empires. Thirteen of the fourteen world empires committed bullet genocides or famine genocides between 1815 and 1914, e.g. the Belgian empire committed genocide in the Congo, the British empire in Ireland and South Asia, the Dutch empire in Indonesia, the French empire in Algeria, the German empire in Namibia, the Italian empire in Libya, the Japanese empire in China, the Portuguese empire in Cape Verde, the Ottoman empire in southeastern Europe, the Qing Chinese empire in Central Asia, and the Russian empire in Circassia.

17 For an overview of the literature on this guerilla struggle, see: Thomas R. Nypaver. Command and Control of Guerrilla Groups in the Philippines, 1941-1945: A Monograph. Fort Leavenworth, Kansas: US Army Command and General Staff College, 2017.

18 Paul Gilroy. The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness. London: Verso, 1993 (37-38). Adorno’s original: “Weil aber der Kunst ihre Utopie, das noch nicht Seiende, schwarz verhängt ist, bleibt sie durch all ihre Vermittlung hindurch Erinnerung, die an das Mögliche gegen das Wirkliche, das jenes verdrängte, etwas wie die imaginäre Wiedergutmachung der Katastrophe Weltgeschichte, Freiheit, die im Bann der Necessität nicht geworden, und von der ungewiß ist, ob sie wird.” Theodor Adorno. Aesthetic Theory. Frankfurt: Suhrkamp Verlag, 1970 (204). This is my translation.

The author is an independent scholar of digital media, video games and transnational media.