Groundxero, is publishing edited excerpts, chronicling the 50 years epic journey of APDR from Nilanjan Dutta’s forthcoming book, Civil Liberties Movement in India. This is the Part 4 (concluding part) of the series focusing on issues taken up by APDR in the new millennium.

With the turn of the millennium, the situation in West Bengal became more alarming from the point of view of human rights. The Left Front government seemed to have joined the so-called ‘war on terror’ as defined by the USA and its allies with the same enthusiasm that it displayed while wooing transnational capital and pursuing the World-Bank-IMF-ADB dictated mega “development” projects, which translated, for the people, as eviction of the poor and suppression of protests. The APDR had its hands full with the task of defending the rights of the evictees.

To read Part 1 click here, to read Part 2 click here and to read Part 3 click here.

Landmark Legal Battle

The 1980s and ’90s saw a spurt in public-interest litigations in India. In early 1989, advocate Pratul Sinha filed a writ petition in the Calcutta high court on the condition of convicts in Alipore jail. On 17 April that year, APDR appealed to the court to be allowed to join the case (C.O. No. 374(W) of 1989) on public interest grounds and sought to extend its scope to cover the condition of under-trial prisoners in several jails. In course of hearing of this PIL, the issue of custodial violence also came up. On 14 July 1989 the organisation filed another PIL at the high court, listing more than 90 custodial deaths between 1977 and 1989. The petition sought punishment of the guilty police officers and a compensation of at least Rs 100,000 to the next of kin of the deceased.[i] The West Bengal branch of the PUCL wrote a letter to the chief justice of Calcutta high court on 28 September the same year giving a list of 71 such deaths.

A few years earlier, on 26 August 1986, advocate and executive chairman of the Legal Aid Services West Bengal, Dilip Kumar Basu, had written a letter to the Chief Justice of India on the need for developing a “custody jurisprudence”, formulating steps for awarding compensation to the victims or their relatives, and ensuring accountability of police officers found responsible for torture.[ii]

The Supreme Court accepted D.K. Basu’s letter as a PIL and subsequently sought affidavits from the central and state governments as well as the Law Commission. It also appointed one of its lawyers, A.M. Singhvi, as amicus curiae to collect information on custodial violence.

By the time the petitions of APDR and PUCL came up for hearing, D.K. Basu had become a judge of the Calcutta high court. Taking the two petitions together, he gave a historic order on 2 June 1992.[iii] Justice Basu instituted a judicial inquiry into all custody deaths from 1977 till 31 May 1992. He directed that “no female suspects shall be taken to or detained in a police station or outpost after sunset”, that they could be interrogated only in the presence of female police officers, special lock-ups should be set up for female suspects in Calcutta and the districts and these should be guarded by women police officers. Further, the court ruled that the state government must pay compensation to victims of custodial violence or to their dependants. An interim compensation of Rs 100,000 should be paid for death or rape, Rs 50,000 for grievous hurt and Rs 20,000 for minor assault or injury within four weeks of the incident. Such incidents should be probed by a “senior higher judicial officer”.

Meanwhile, the D.K. Basu v. State of West Bengal case[iv] continued in Supreme Court. In 1996, the apex court said in its judgement that “torture is more widespread now than ever before”. It observed that custodial torture was “a naked violation of human dignity and degradation which destroys, to a very large extent, the individual personality. It is a calculated assault on human dignity and whenever human dignity is wounded, civilization takes a step backward.” As a remedial measure, the court issued an 11-point guideline. Making the authorities honour this guideline has since been the subject of a continuous struggle by civil liberties groups all over the country.

Millennial Issues

With the turn of the millennium, the situation in West Bengal became more alarming from the point of view of human rights. The Left Front government seemed to have joined the so-called ‘war on terror’ as defined by the USA and its allies with the same enthusiasm that it displayed while wooing transnational capital and pursuing the World-Bank-IMF-ADB dictated mega “development” projects, which translated, for the people, as eviction of the poor and suppression of protests. The APDR had its hands full with the task of defending the rights of the evictees.

In this phase, the APDR also actively associated itself with the anti-nuclear movement. After the Pokhran test blast in May 1998, it joined the campaign against nuclear weapons. Soon after, when the Left Front government declared its intentions to set up a nuclear power plant in West Bengal, the APDR with other organisations, particularly the ‘people’s science’ groups, initiated a campaign against hazardous nuclear power as well. The anti-nuke activists were beaten up and arrested, but the state government was forced to shelve its audacious nuclear power project in the ecologically fragile Sundarban biosphere reserves.

Following the suicide attacks on the US in 2001, when governments the world over started reinforcing their armoury of repressive laws on the pretext of hunting for terrorists, the West Bengal government was all too eager to join the bandwagon. It drafted the Prevention of Organised Crime Ordinance (POCO). The draft, far from being put up for a democratic discussion, was not even disclosed to the ruling Left Front partners. When the APDR managed to procure and circulate the document, its contents created a flutter among members of the civil society. For, they found it similar in letter and spirit to the Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) of the Union government. It also bore an uncanny resemblance to the PATRIOT Act of the US. The state government initially tried to assuage them saying it would revise the draft and place it in the Legislative Assembly to be passed as Prevention of Organised Crime Act (POCA), rather than an ordinance. It became apparent that the “revision” was merely eyewash, and ultimately the government had to drop the idea “temporarily” in the face of public opposition.

A copy of the draft, along with the APDR’s comparative analysis of POCA and similar Acts, was mailed to Noam Chomsky immediately after he visited West Bengal during this time. In an e-mailed response to APDR, he wrote: “I did have a chance in India to talk a few times about POTO [the Central ordinance preceding POTA] in interviews, but hadn’t heard about this. It wasn’t brought up in the few brief news conferences scheduled in Calcutta, or in other meetings. There is a plague of such legislation throughout the world, here too. It’s a very dangerous development, and should be resisted everywhere.”

Arrest and torture of radical Left activists and common people suspected of supporting them continued, not only in the remote villages but also in the city of Kolkata and its suburbs. The ranks of political prisoners thus began to increase again with alleged People’s War or Maoist Communist Centre activists and sympathisers. The Naxalites were not the only ones to face such repression. The minorities, too, suffered in the wake of the prevailing Islamophobia.

By the end of 2002, APDR documented case details of 402 persons arrested as suspected Naxalites over the preceding two years and said it had reasons to believe that there were at least 300 more. Besides, 1,000 activists of the ethnic Kamtapuri movement in north Bengal and 47 alleged activists of the Students Islamic Movement of India were held on the basis of mere suspicion. Even 22 activists of the Akhil Bharatiya Nepali Ekta Samaj, who supported the democratic movement in Nepal, had been slapped with a case of conspiracy against the State of India in Siliguri. Demanding the release of all of these prisoners, the APDR submitted a memorandum to the Speaker and all members of the West Bengal Legislative Assembly on 10 December 2002.

On the other hand, evicting the poor people without proper rehabilitation in the name of urban and industrial development became the order of the day all over the country including West Bengal. Unprecedented public protests took place at Singur in Hooghly district in 2006 and Nandigram in East Midnapore district in 2007 over the acquisition of agricultural land by the government for handing over to big industrial houses for setting up ‘special economic zones’. In Singur it was the Tatas, while in Nandigram it was the Salim Group, notoriously associated with the massacre of communists in Indonesia. The police and ruling party cadres massacred at least 14 people on 14 March 2007 in Nandigram, but failed to break the resistance. The APDR fought a legal battle up to the Supreme Court that resulted in a landmark order on the government to return the plots to the Singur peasants who were unwilling to part with their land. It also sent a fact-finding mission to Nandigram immediately after the carnage and staged numerous protests.

Two issues that brought the APDR the maximum public and media attention during this decade, however, did not concern political or even economic rights in the traditional sense but belonged to the wider domain of human rights. One was its vigorous campaign for the abolition of capital punishment ﴾the immediate concern being the death sentence on Dhananjoy Chatterjee, accused of a schoolgirl’s rape and murder ﴿ and the other was exposing the role of police officers and socially powerful persons behind the death of a not-so-well-off Muslim youth, Rizwanur Rahman, who had loved and married an industrialist’s daughter.

On the other hand, activists of the APDR stood helpless and bewildered when, within a couple of days of the protests over Rizwanur’s death and Nandigram violence, religious fanatics engineered a violent agitation demanding that Bangladeshi anti-fundamentalist writer Taslima Nasrin be banished from Kolkata. The APDR supported the writer’s right of residence in the city of her choice, but she had to leave in the end. Many suspected that the agitation was planned to divert attention from issues such as Nandigram and Rizwanur.

The biggest mass upsurge after Singur and Nandigram took place at Lalgarh in West Midnapore district in 2008 against police atrocities during anti-Maoist operations. Supporting this movement once again brought the charge on the APDR of being a Naxalite front, but that did not deter it from siding with the people’s cause.

On the eve of the West Bengal Assembly elections in 2011, the APDR, Bandimukti Committee (BMC) and other organisations again raised the issue of release of political prisoners. This election saw the ending of the 34-year long Left-Front rule and a new incarnation of the Congress party, which called itself the Trinamool (grassroots) Congress, coming to power.[v] However, the victorious leaders turned down the demand for the release of political prisoners which they had promised during their election campaign. Instead, the new government set up a ‘Review Committee’. Amid intense debate in the APDR on whether civil liberties activists should join the committee, its secretariat member Sujato Bhadra accepted the government’s invitation. The committee though, wound up midway without having any bearing on the government’s policy. Some political prisoners came out in ones and twos through the usual, time-taking legal process. Maoist leader Kishenji (Mallojula Koteshwara Rao) was killed by the state forces on 24 November 2011.

However, the APDR has been able to make some significant legal interventions regarding jail conditions and deaths in judicial custody. On 15 September 2017, the Supreme Court, hearing a writ petition (WP (C) 406 of 2013), had directed that the state could not avoid responsibility for deaths in its custody and pay compensation in case of unnatural deaths in prison. It instructed all High Courts to initiate suo motu PIL in this respect. APDR wrote to the Chief Justice of Calcutta high court and a PIL was initiated (WP 26371 (W) of 2017). Then, it compiled a report on the basis of official replies to its queries under the Right to Information (RTI) Act and information gathered from the prisoners’ family members, which it submitted to the high court. The court allowed APDR as an ‘intervener’. Meanwhile, the Supreme Court on 8 May 2018 directed all high courts to initiate two more PILs, one to reduce overcrowding of jails and another to arrange filling up of vacant posts in prisons. Two new PILs were thus initiated (WP 8573 (W) of 2018 and WP 6855 (W) of 2018) and APDR continued to submit information and bring to the court’s notice the abject condition in prisons in the state. On 11 October 2018, the high court directed the state government to award interim compensation of Rs 3 lakh to the nearest of kin of prisoners suffering unnatural death. Finally, in November 2019, a scheme for awarding compensation was notified by the government of West Bengal. Perhaps this is the first time a state government has formulated such a scheme.

In course of its journey in the post-Emergency phase, the APDR has extended its concerns to newer areas. Way back in 1999, it initiated a campaign for a ‘no choice’ tab on the voting machines or ballot papers. It also filed a PIL in Calcutta high court demanding this right. The case went up to the Supreme Court, but at that time, the courts were convinced by the plea of the Union government that since voting was not mandatory under the Indian Constitution, a citizen could choose to abstain. Subsequently, the PUCL and others filed fresh petitions in the Supreme Court. The hearings went on for nine long years. At last, on 27 September 2013, the apex court directed the Election Commission to provide for a ‘none of the above’ (NOTA) button. The APDR has since launched fresh campaigns to take this gain further. It is demanding the extension of the NOTA facility to local self-government bodies’ elections and the ‘right to recall’ through referendum of any elected candidate who fails to deliver and thus loses the people’s trust.

It has taken up environmental issues on several occasions and has been consistently fighting for the ‘right to clean environment’ since the 1980s. The case of the Calcutta Metro Rail construction workers falling sick inside the compressed-air tunnels and a marathon struggle to recover the almost-lost Sonai River from the clutches of the development mafia are prominent examples. It launched a legal battle in March 2017 at the high court and Supreme Court to thwart an international highway widening project driven by sheer speedomaia that envisioned the felling of more than 4,000 centuries-old trees along Jessore Road in North 24-Parganas district near India-Bangladesh border. APDR has brought to the fore the concept of ‘Heritage Tree’ and both the HC and the SC had to appoint experts to explore alternatives to the government’s idea of so-called development.

*Edited excerpts from Nilanjan Dutta’s forthcoming book, Civil Liberties Movement in India. The author is a human right activist and an independent journalist.

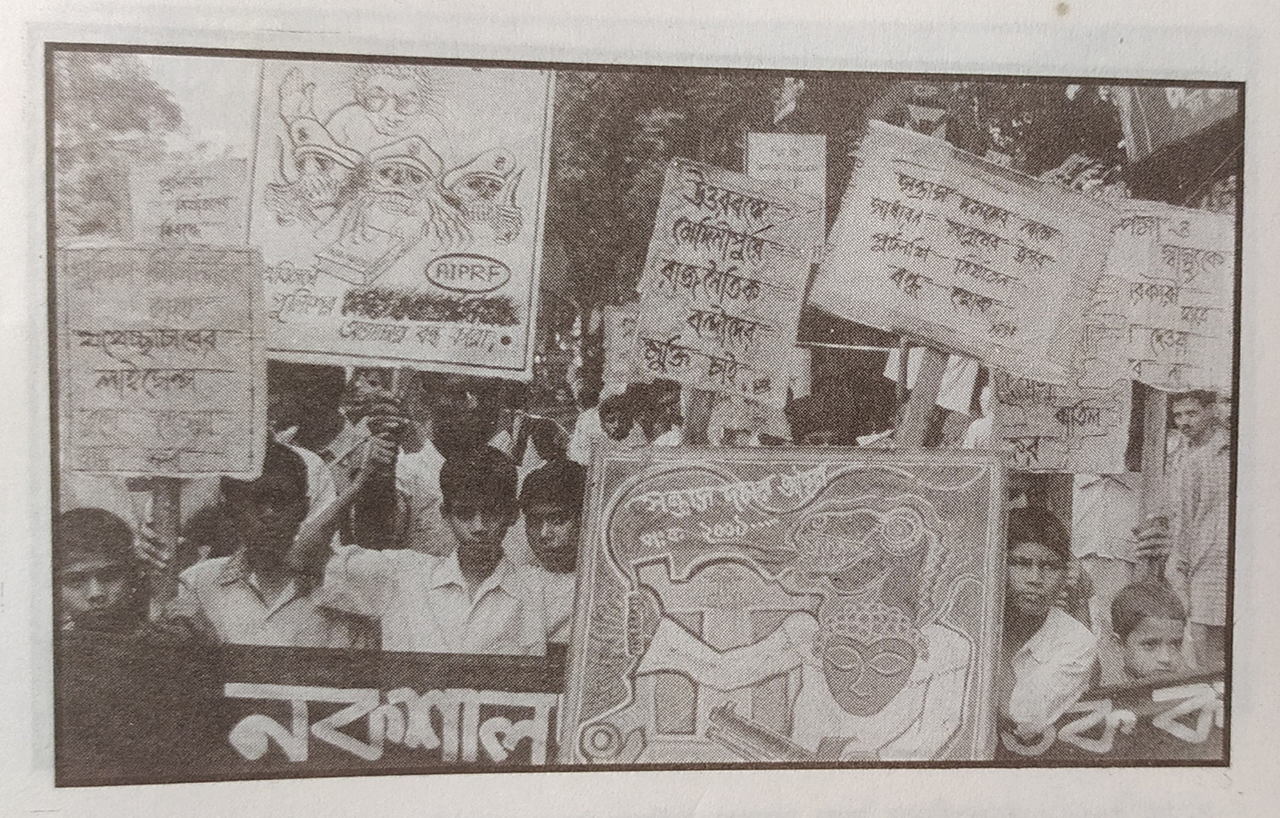

*Cover Image : APDR’s rally for release of political prisoners in 2002

Reference :

[i] Adhikar, March 1990.

[ii] Amnesty International, Combating Torture: a manual for action, AI Index: ACT 40/001/2003.

[iii] The Telegraph, Calcutta, 3 June 1992.

[iv] Basu v. State of West Bengal, 18 December 1996, [1997] 2 LRC 1.

[v] For a comprehensive account of the state of civil liberties under the 34-year-long Left Front regime, see Dutta, Nilanjan, Rights and the ‘Left’.