Association for Protection of Democratic Rights (APDR) is one of the oldest human rights organisations in India. Formed in 1972, amid the “orgy of slaughter and brutal repression” unleashed by the Indian State on political activists, in the background of the Naxalbari uprising, APDR turns 50 this year.

25 June 1972 — when the first declaration of APDR was adopted and its first committee was constituted is taken as its foundation day. No political party can claim credit for founding the APDR and till now it has been able to maintain organisational independence from all parties and groups. Yet, it has been portrayed as a front organisation of the Naxalites or Maoists by successive governments. That is because it has been most vocal in defence of the democratic rights of the communist revolutionaries who are the most persecuted of all opposition groups under any regime.

On the eve of APDR’s 28th conference scheduled to be held on 23-24 October, at Sheoraphuli, in Hooghly district of West Bengal, Groundxero, will publish edited excerpts, chronicling the 50 years epic journey of APDR from Nilanjan Dutta’s forthcoming book, Civil Liberties Movement in India. Nilanjan Dutta, member of APDR, is a human right activist and an independent journalist.

The excerpts will be published in parts. Part 1 comprises brief life-sketches of a few of the people who came together to form APDR in 1972. It reveals the diversity of the founders’ social, professional and political backgrounds. And at the same time also point to the thread that joined APDR as a civil liberties organisation with its predecessors.

The Pioneers

Amid the suffocating atmosphere in West Bengal prevailing in the wake of the state terror unleashed to crush the Naxalite movement, some people had become desperate to find a way to breathe. Among them, those who had seen the colonial days and had fought for freedom, felt that “the orgy of slaughter and brutal repression that have been sweeping for last two years all over India was unknown even in the days of British Raj”.[i]

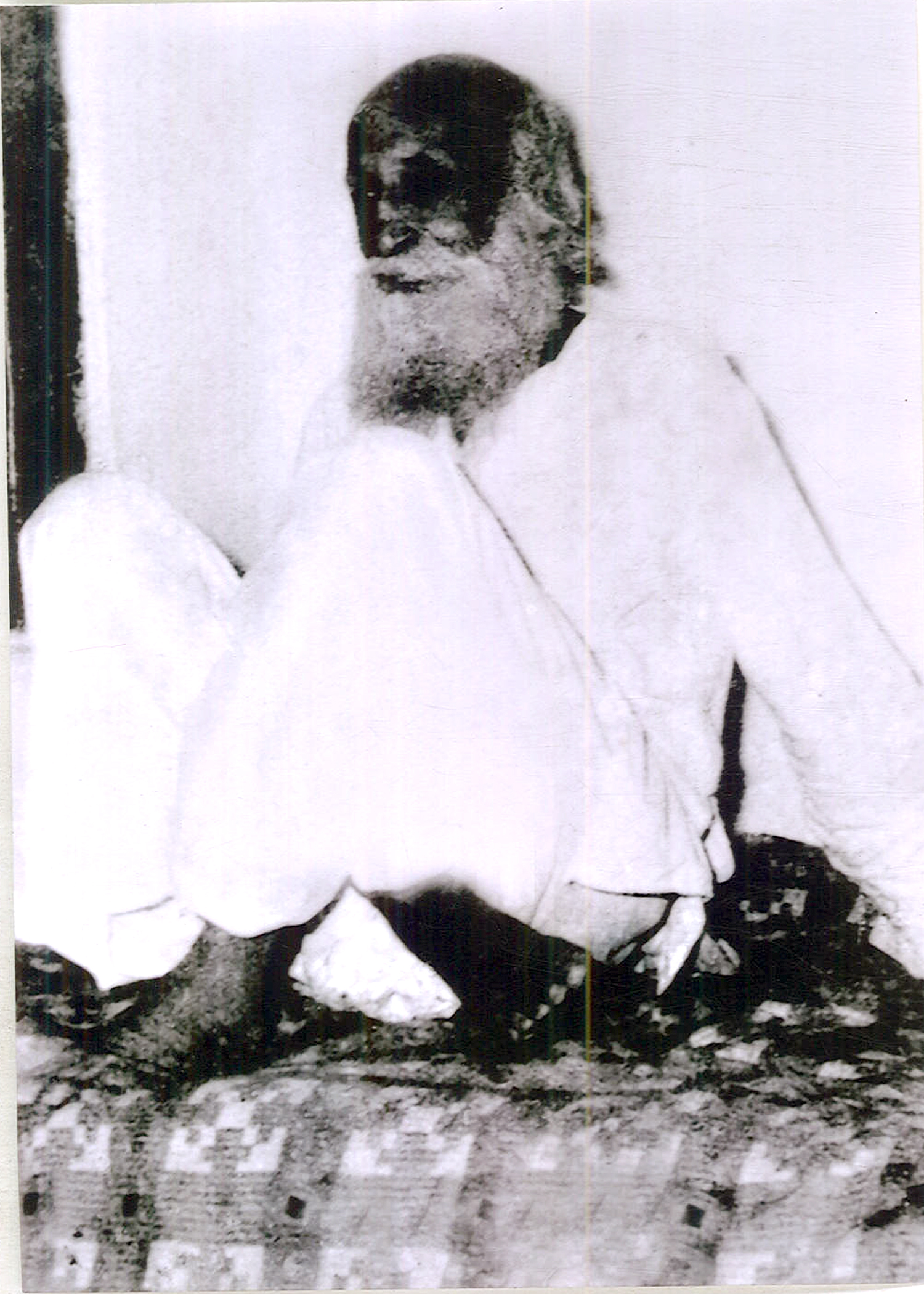

One such person was Sushil Bandyopadhyay [1902-1976], who had spent 30 years of his life as political prisoner and internee before Independence and again went to jail in 1968. He was an old man by that time, fondly called ‘Dadu’ (Grandpa) in his south-west Calcutta neighbourhood of Behala. Legend has it that seeing the police drag away two boys barely out of their teens, he blocked their way spreading out his arms like the wings of a mother bird eager to protect her young and rescued them from possible slaughter. Despite keeping out of limelight, he still commanded great respect from many people of position who had been his followers during the freedom struggle.

Another person like him was Promode Sengupta [1907-1974], an associate of Subhas Chandra Bose and a former minister in the Azad Hind Government. He had also played an active role in the Civil Liberties Committee (CLC) formed before Independence, first as its joint-secretary and later as secretary. He was also working with the ‘Marxist group’ within the Forward Bloc after coming back to India after the war. Intelligence reports, however, said that he was actually a communist mole in the Forward Bloc and it was the CPI which told him to join the CLC. This well-known freedom fighter was arrested in “free” India under the Preventive Detention Act in 1950.[ii] When the 1967 uprising took place, both Bandyopadhyay and Sengupta became actively involved in the Naxalbari O Krishak Sangram Sahayak Committee (Naxalbari and Peasant Struggle Solidarity Committee). Sengupta also joined the All-India Coordinaion Committee of Communist Revolutionaries (AICCCR), though he later fell out with Charu Mazumder and other leaders.

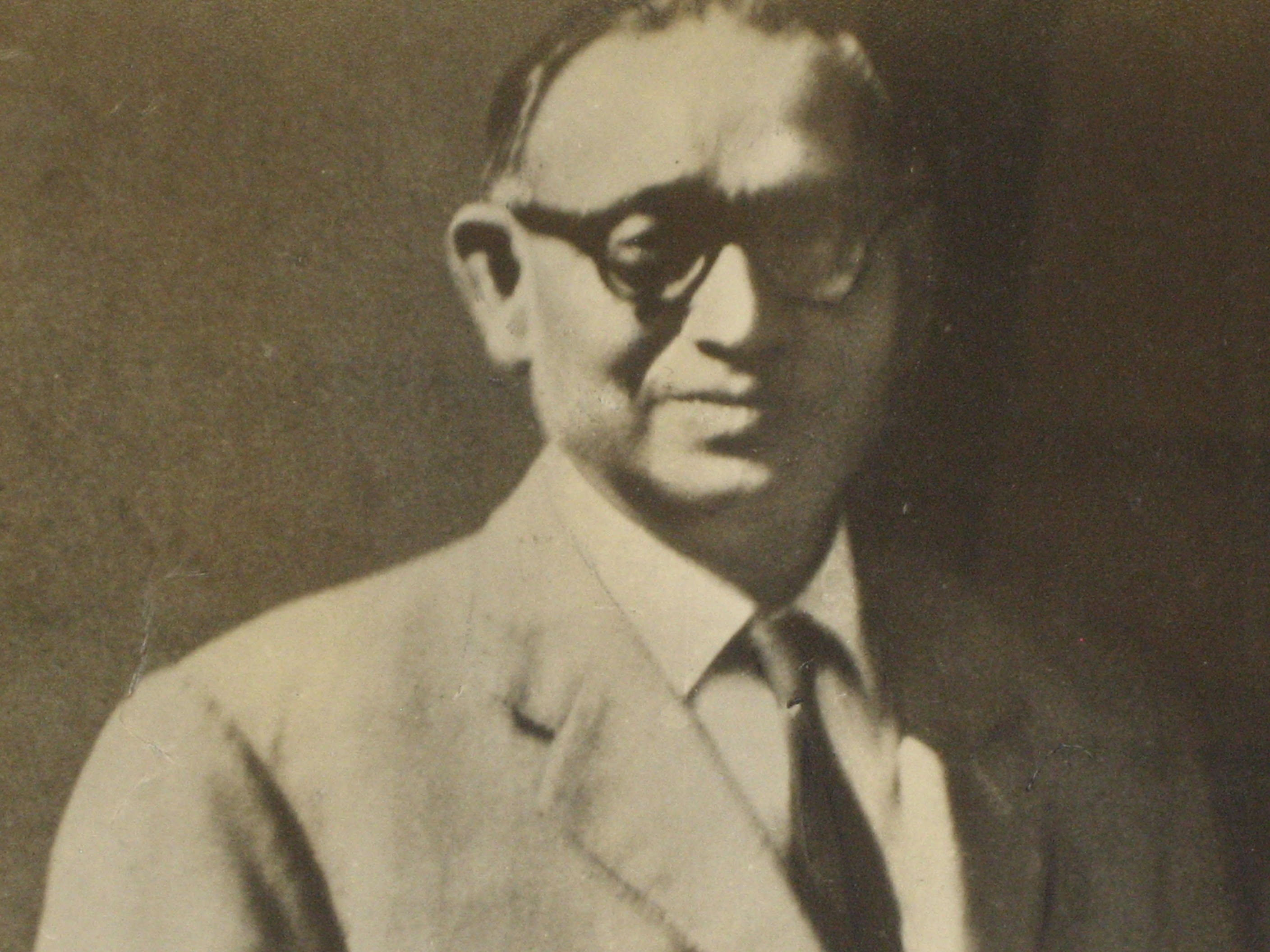

Dr Amiya Kumar Bose [1900-1975] was a leading cardiologist of Calcutta. He was never a member of the communist party, but was close to many communist leaders and intellectuals. He was actively associated with a number of Left-inspired social and professional organisations including the Students’ Health Home, Peoples’ Relief Committee and Indian Medical Association. The road where he used to live is now named after him.

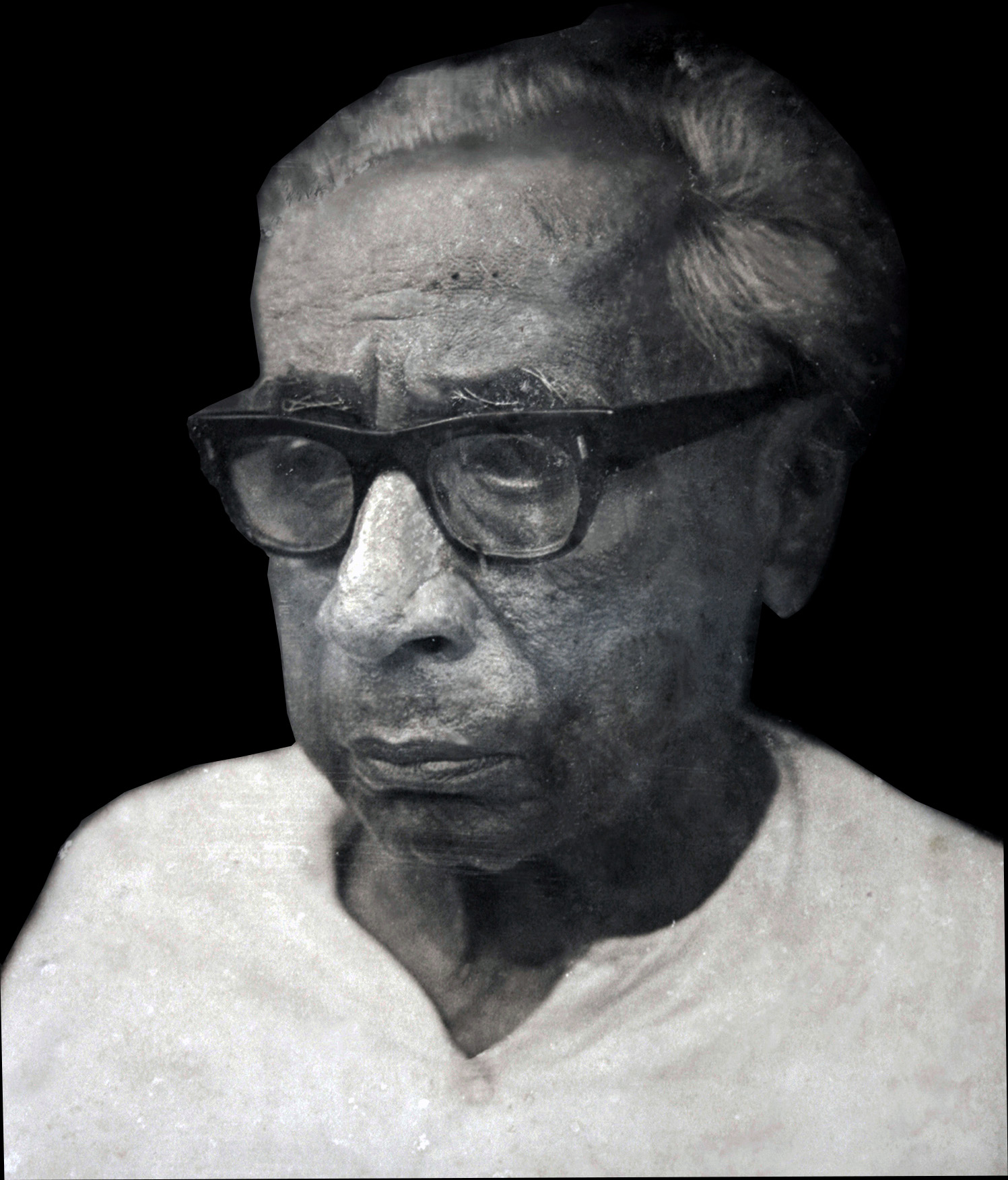

Kapil Bhattacharya [1904-1989] was a civil engineer who did some innovative experiments with concrete, lived in France for a while and wrote in both French and Bengali progressive literary magazines. After coming back to India, his interest was turned towards the character of rivers. He became a pioneering critic of big dam projects at a time when these were regarded as the “temples of modern India”. For this blasphemous view, the corporate Press branded him as a traitor to the nation. Kalyani Bhattacharjee [1907-1983] was an organiser of the student movement and militant women’s movement and a participant in the revolutionary movement in colonial Bengal. She spent many years in prison and under internment. Her younger sister and a member of her organisation Chhatri Sangha, Bina Das, had fired at Bengal Governor Stanley Jackson at the Calcutta University convocation hall in 1932. After her marriage, Kalyani went to live with her husband in Bombay and got involved in the civil liberties movement there in the 1940s. She was also imprisoned there for her participation in the Quit India Movement. Back in Bengal after her release, she devoted herself to the work of famine relief. She contested the first general election as a candidate of the Praja Socialist Party (PSP) and lost as her party had no funds for campaigning which her rival Congress candidate had aplenty. That was her first and the last involvement in electoral politics. Activist-lawyer Abdul Latif had been an assistant secretary of the CLC in 1946-47. He went over to Pakistan during Partition, did the Communist Party’s underground work there and was jailed in 1949. He came back to India after being released in 1953 became a trade unionist. He dropped his party membership in 1966. APDR’s first joint assistant secretary Sanjay Mitra has said in his reminiscence on the early days of the organisation that it was Latif who had suggested the name ‘Association for Protection of Democratic Rights’. Latif though has said in his own memoir that the name was given by a fellow lawyer called Ajit Dutta, who was “very enthusiastic about forming a civil liberties body”. Dutta had asked Latif to write a draft declaration for the organisation. He wrote it and discussed it with some others lawyers before the first preparatory meeting for the organisation. At the meeting, Sanjay Mitra said it lacked spirit. Then, Mitra was asked to prepare another draft. Dutta and some others found Mitra’s draft too political and they backed out, but Latif stayed on for some more time.[iii]

Sanjay Mitra and some of his comrades belonged to a political organisation called the National Liberation and Democratic Front (NLDF). This group consisted of mostly young activists, who were tempered by the revolutionary fire of Naxalbari and joined the AICCCR, but kept out of the Communist Party of India (Marxist-Leninist) or CPI(ML) as they could not agree to its political formulations and formation process. Strongly influenced by Sushil Bandyopadhyay, they had taken it as a political task to form a civil liberties organisation.

These are brief life-sketches[iv] of only a few of the people who, amid the “orgy of slaughter and brutal repression”, came together to form APDR. These reveal the diversity of their social, professional and political backgrounds. And these also point to the thread that joined the APDR as a civil liberties organisation with its predecessors.

No political party can claim credit for founding the APDR and till now it has been able to maintain organisational independence from all parties and groups. Yet, it has been portrayed as a front organisation of the Naxalites or Maoists by successive governments. That is because it has been most vocal in defence of the democratic rights of the communist revolutionaries who are the most persecuted of all opposition groups under any regime. In fact, the revolutionary outfits have always been ill at ease with those who fight for “bourgeois” democratic rights. However, in the beginning, several medium and small Left parties apart from the NLDF, such as the RSP, Forward Bloc, Socialist Unity Centre (SUC) and Workers’ Party took it as a serious task to constitute a civil liberties organisation at that juncture. So, several of their members joined or actively supported it. Individually, even one or two Congress and CPI leaders had been involved. On the other hand, Saumyendranath Tagore, who was very active in the civil liberties movement in the 1930s, dropped out at its planning stage. At a meeting in his house, he could not agree with the demand of unconditional release of all political prisoners. Those who had murder charges must face trial, he said. Promode Sengupta contested him saying one could not expect a fair trial in the prevailing situation. And besides, they did not commit any murder for their own interest. Whatever they had done was for a political cause and so, they should be given the status of political prisoners and released unconditionally. After that, a meeting was held at the house of Calcutta Municipal Corporation councillor Baren Daw of RSP, where the organisation took shape. Kapil Bhattacharya readily agreed to be the president and also to let the living room of his house to be used as its office.[v]

The first committee of the APDR included the following office-bearers:

Kapil Bhattacharya (president)

Kalyani Bhattacharjee (working president)

Sushil Bandyopadhyay (vice-president)

M.A. Latif (vice-president)

Barendra Krishna Daw (vice-president)

Saroj Chakraborty (vice-president)

Dr Amiya Bose (vice-president)

Promode Sengupta (general secretary)

Dilipkanti Chaudhury (joint assistant secretary)

Sanjay Mitra (joint assistant secretary)

Amal Bose (treasurer)

There were 30 other founder members. They were:

- Kshirod Dutta, freedom fighter

- Asit Ganguly, advocate

- Dulal Bose, journalist

- Satyananda Bhattacharya, journalist, trade unionist and ex-councillor, Calcutta Corporation

- Kanai Paul, ex-MLA

- Suhasini Devi, freedom fighter

- Guruprasanna Ghatak, advocate

- Utpal Dutt, dramatist

- Nalini Sur, advocate

- Subhas Chandra Ganguly

- Sudhir Mazumdar, advocate

- Mrityunjay Dasgupta

- Sova Sen, actor

- Mrinal Sen, film director

- Santosh K. Roy

- Pinaki Chatterjee, sea-explorer

- Adhir K. Mukhopadhyay

- Tilottama Bhattacharya, journalist

- Indrajit Gupta, CPI MP

- Dr Bijoy Kumar Bose

- Dr Dhirendra Nath Ganguly

- Dr Bimal Bhattacharyya

- Dr Angshuman Ganguly

- Bina Dhar

- Debashis Ganguly

- Rashbehari Ghosh

- Manoj Kumar Sadhu

- Biswanath Prasad Adhikari

- Binayak Dutta Roy

- Sudhi Pradhan

Some of the above were quite famous people in their respective fields, while some others were young activists at that time. We must mention the names of a few more persons who were not even in the committee, but were there from the very beginning and contributed a lot to the organisation. One of them was Santi Sarkar. She was a member of the Workers’ Party of India and took an active part in the formation of the organisation. It was she who had brought in Kalyani Bhattacharjee who became the first working president of APDR and also convinced her own party about the need for supporting the civil liberties movement, according to old-timers of the Workers’ Party of India like Sukhendu Bhattacharya. Bharati Chatterjee came from the student movement and brought some of her comrades into the process of formation of APDR. Those who had worked with her said that she performed the role of its office secretary in the initial days, meticulously sorting and filing every report and every newspaper clipping, going through every letter that reached the office and replied to it. Her work prepared the ground for APDR’s encyclopaedic publication, Bharatiya Ganatantrer (?) Swarup, which exposed before the world the state terror that was prevailing in the country. We will come to that part later. Biren Banerjee used to run a printing press in central Calcutta where many of the APDR publications, including Bharatiya Ganatantrer (?) Swarup, were printed. He was an associate of Sushil Bandyopadhyay in the freedom struggle and was sentenced to death by the British, which was commuted to life imprisonment. Later, he joined the CPI and was elected as an MLA from Howrah in the 1950s. He and his nephew Radharaman Banerjee had to suffer severe police torture and huge financial losses because of doing the APDR’s printing jobs.

First Declaration

The date of the meeting — 25 June 1972 — where the first declaration of APDR was adopted and its first committee was constituted is taken as its foundation day. The declaration was issued at a Press conference on 9 September the same year. The beginning of the declaration is notable:

DEMOCRATIC and human rights are the indispensable preconditions for the development of individual and society. Over centuries, people of all lands have been in the ceaseless struggle for attaining these fundamental rights and getting them well-entrenched and expanded in their social organisations.

In India, too, tradition of movement for achieving these human rights forms a glorious chapter of our history. In days of the British whenever the alien rulers struck at the national and democratic movement, robbed us of the fundamental human rights and resorted to repression and detention without trial, the people from all walks of life came forward to protest against those.

It was in this way that the people of India have been fighting without respite over a long period for a number of basic human rights, which ultimately won constitutional recognition. These are freedoms of association, freedom to call mass meeting, freedom of religion and political belief and right to have a secure life, etc. The solemn promise that these rights will remain unchanged and be protected by the prevalent laws of the Indian Union have also been enshrined in the constitution.

Three aspects merit attention in this preamble. First, the activists in this phase had begun to speak in the language of universal human rights, while putting emphasis on the protection of ‘democratic rights’. Second, even as they set it in a global context — where “people of all lands have been in the ceaseless struggle” — they were well aware of the legacy of the movement in India and called it a “glorious chapter of our history”. And third, they based their claims on the “solemn promise” of the Constitution of the country to preserve the hard-earned fundamental rights.

Thus, with their feet firmly on the ground and vision clear and far-reaching, they set out to challenge the “reckless abuse of power in the name of maintaining law and order”. They indicted the state’s tyrannical activities on three counts: that these “stand against humanity, are illegal and undemocratic”. Here we can see that universal, legal as well as democratic principles are invoked together to prepare a strong moral ground for the movement. Towards the end of the declaration, there is an appeal to all sections of our people including workers, peasants, intellectuals and students — whatever differences of opinion and party affiliation we have, let us agree to a united effort to end this reign of terror and repression and also to end mutual in-fighting amongst us.

The framing of the appeal shows that the founders of APDR wanted to achieve a social as well as political unity within the rights movement. The last part is very specific to the contemporary context — hostilities not only between the radical and parliamentary Left but also amongst the various groups and streams of the radical Left had reached fratricidal proportions which needed to be put a brake to. However, this infighting never stopped totally, although the degree of violence has varied.

In the first declaration, the APDR made two appeals: first, it urged the people to set up its branches in their own localities and second, it requested the “relatives and friends of political detainees, victims of slaughter arid repression due to political reason” to contact its office at Kapil Bhattacharya’s residence, 18(N) Madan Baral Lane, Calcutta 12.

The first appeal got good response from the beginning; like the Civil Rights Committee of 1918, its branches came up one after another, beginning with Berhampore (Murshidabad district), Midnapore (Midnapore district) and Shantipur (Nadia district). It was these branches that became its source of sustenance and eventually helped APDR become the oldest and widest functioning civil liberties organisation in India. Though news of the formation and activities of this organisation was hardly covered by the big Press at that time, people came to know about it through small but popular periodicals such as Frontier. Having read a report in this news magazine, well-known former Congress politicians turned civil liberties and social activists from Orissa, Nabakrushna Choudhuri and his wife Malati Choudhuri, wrote to Kapil Bhattacharya expressing interest in forming a similar organisation in their state. Nabakrushna Choudhuri was the first chief minister of Orissa. People also got in touch from Bihar, Delhi and abroad.

*Edited excerpts from Nilanjan Dutta’s forthcoming book, Civil Liberties Movement in India. The author is a human right activist and an independent journalist.

Reference

[i] From the First Declaration of APDR issued on 9 September 1972.

[ii] West Bengal State Archives, I.B. Files on Promode Sengupta, No. 10 H.S. dated 24.4.1950.

[iii] M.A. Latif, ‘Adhikar Andolane Dirgha Path Periye’, pp. 60-61.

[iv] For these life-sketches, I have mainly relied upon the reminiscences of Sanjay Mitra, Subhas Ganguly, Debangshu Dasgupta, M.A. Latif, Rana Bose (son of Dr Amiya Kumar Bose), Pradyumna Bhattacharya (son of Kapil Bhattacharya), Jayabrata Bhattacharjee (son of Kalyani Bhattacharjee), Kamala Das Gupta (associate of Kalyani Bhattacharjee), as well as my own research on Promode Sengupta (in APDR 1972-2002: 30 Years of Fight for Rights, Kolkata, APDR, 2003, pp. 33-36).

[v] Unless otherwise mentioned, the above and following account of the formative days of APDR is based mainly on two memoirs: Sanjay Mitra, ‘Sroter Biparite’ (Against the Stream), in Nilanjan Dutta (ed), Panch Prajanmer Naxalbari (Naxalbari of Five Generations), Kolkata, Purbalok Publication, 2018, pp. 46-63 (esp. 57-63); and Subhas Ganguly, ‘APDR-er Shurur Dinguli’ (The First Days of APDR), in Two Decades of APDR and Human Rights (bilingual), Calcutta, APDR, 1991, pp 89-112. The APDR office files have obviously been the most important primary sources. Some of the information are drawn from my pamphlet: Dutta, Nilanjan, Violation of Democratic Rights in West Bengal since Independence, (ed) A.R. Desai, Bombay, C.G. Shah Memorial Trust, 1985.

Courtesy (for all pictures together): ‘APDR 1972-2002: 30 Years of Fight for Rights’ and various sources.

A commendable job done.