Yesterday, May 26, was observed by the Samyukta Kisan Morcha (SKM) and the Central Trade Unions (CTU) as Black Day. While such worker-peasantry solidarity is much needed and praiseworthy, the precarious realities that majority of the Indian workers are facing today are not going to be addressed by mere demonstration of such unity. Infested with virus and fungi, lockdown induced massive retrenchment, hunger and atrocities by the police, the anti-labour policies of the government and the oppression of company owners, the workers are in urgent need of powerful grassroot movements in order to survive. Writes Gurupada Dhar.

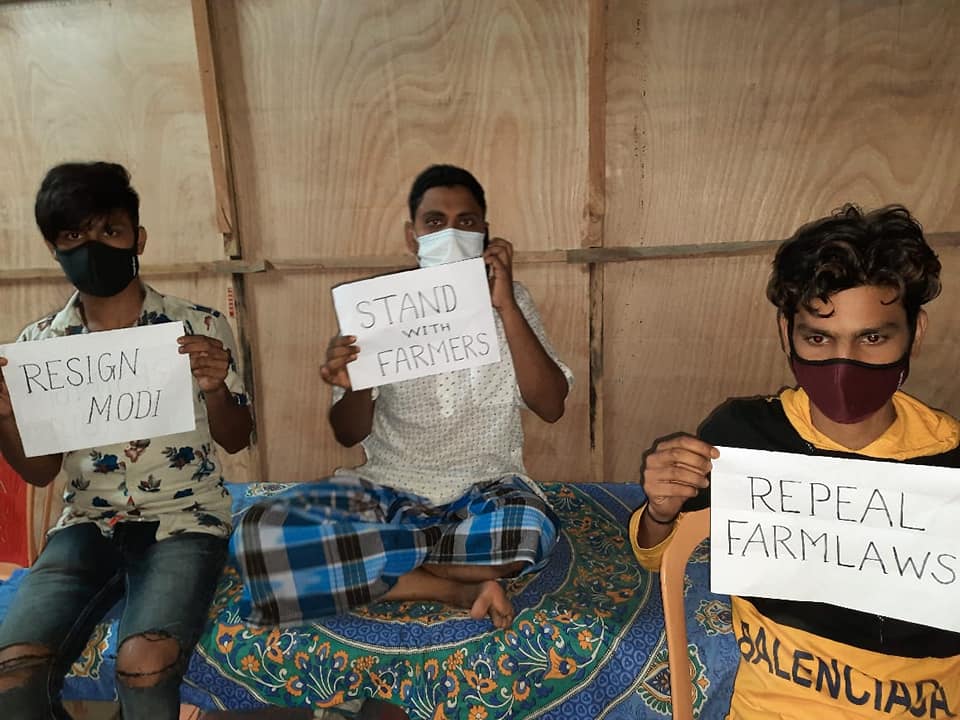

Followed by the rally of thousands of farmers on May 24 in Hisar in Haryana, the protesting farmers observed May 26 as Black Day by burning effigies and demonstrating with black flags. The day marked half a year of the farmers’ movement that began on November 26, 2020 and coincided with the day Narendra Modi took oath as the Prime Minister in 2014.

The farmers’ movement to repeal the three pro-corporate farm laws passed by the Modi government is still going strong, drawing mass support in Punjab, Haryana, Western UP and elsewhere. The Samyukta Kisan Morcha, so far, has skilfully maintained unity and solidarity amongst the various individual peasant unions with diverse political and ideological leanings. The struggle has survived constant maligning attempts by the government, ruling party and media. The recent protest by the farmers in Hisar even managed to make the state administration bow down and announce revoking of criminal cases lodged against the farmer leaders. At almost every step, the farmers’ movement has provided hope to a large number of people in this country in their struggle against the fascist rulers in Delhi. But can the same be said about the protests by the CTUs?

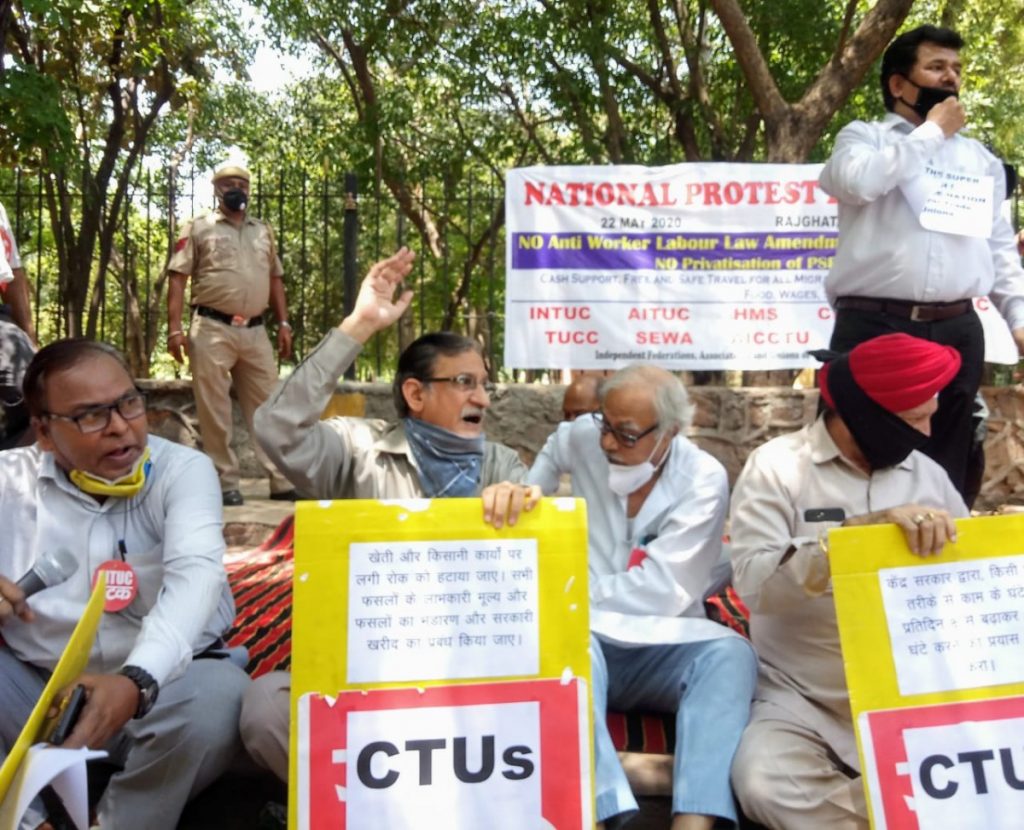

In continuation to the joint struggle with the farmers’ unions, the CTUs continue to work together with SKM, organizing joint demonstrations and other protest programmes demanding repeal of the three Farm Laws, four Labour Codes and the Electricity (Amendment) Bill. It is to further intensify the joint effort, the CTUs have supported the SKM’s Black Day call. The ten CTUs in the joint forum are Indian National Trade Union Congress (INTUC), All India Trade Union Congress (AITUC), Hind Mazdoor Sabha (HMS), Centre of Indian Trade Unions (CITU), All India United Trade Union Centre (AIUTUC), Trade Union Co-ordination Centre (TUCC), Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), All India Central Council of Trade Unions (AICCTU), Labour Progressive Federation (LPF) and United Trade Union Congress (UTUC).

However, whether the CTU-SKM alliance should be considered as the much-needed wind in the sail of the working class movement in this country is still unclear. The doubt lies not in the alliance, but in the fact that on their own, the CTUs have not been able to raise any such tangible hope of meaningful struggle among the oppressed majority of the Indian workforce – in particular, the unorganized sector that faces the severest attack from the neoliberal state-capital nexus backed by an ultra-nationalist right-wing fascist government.

CTU activities – even within the permanent workers – remain primarily limited to wage and other benefits haggling with the company management. Rarely do the CTUs significantly venture towards more political demands exposing and sharpening the contradictions of the workers with the neoliberal capitalist order. This problem is related to, barring a few exceptions, a certain degree of monopoly held by the CTUs affiliated to mainstream political parties over the permanent workers. The CTUs have in most cases failed to protect the rights and have even betrayed the casual or contractual labourers in the formal sector. These labourers constitute the major part of the labour force in the production units. As for retrenchment, the companies now do not really need to retrench permanent workers anymore as the brunt is fully borne by their casual or contractual counterparts. Even if there is a CTU protest against retrenchment, more often than not it ends with a quick settlement with the management – based on a partial or full acceptance of retrenchment of the casuals. In most cases these workers are not even eligible to be union members. On the other hand, although the CTUs indeed have a significant presence in several informal sectors such as sanitation work, Anganwadi, health work, construction work etc., the movements barely comprise much besides the same token strikes and cheap settlements. When it comes to migrant workers, the situation is the bleakest.

In addition, the new labour codes, doing away with many labour-rights and curtailing the legal scope for workers to unionize, are ready to tilt the balance of power further towards the company owners, allowing them to hire and fire workers as they please.

The biggest difference between the observation of Black Day by the SKM and the CTUs lies in the fact that for the farmers, the protest day is a reiteration of an ultimatum thrown at the government – as the farm unions have already announced their intention to intensify the struggle more if their demands are not paid heed to. Whereas, for the CTUs, the observation of this day is merely symbolic, essentially limited to showing solidarity and not much else. Their generic calls for repealing the labour codes and ritualistic yearly strikes have so far not inspired the workers to any significant struggle of the nature of the farmers’ movement even within the permanent factory workers in the organized sectors, who the CTUs primarily represent (perhaps the reason lies therein).

The combined attack of the pandemic, lockdown and the government’s policy to use the health crisis as an opportunity to push through more stringent neoliberal economic reform measures has revealed how severe is the need to overcome such limitations of the CTUs and other workers federations. The Indian workers are in need of grassroot level organizations and movements that address their fundamental rights to life and livelihood, not just a factory level body to negotiate wage increments. The trade union movement has so far been inadequate in organizing and leading struggles to provide justice for the working masses from neoliberal capitalist exploitation, which has put even the basic survival of the working masses at risk.

Beaten by Sticks

Rising Covid infections and imposing lockdowns to contain the spread of the virus has by now become synonymous. Month long frequent lockdowns in itself means loss of livelihood, retrenchment, unemployment and hunger for millions of daily wage earners. Coupled with this is the zeal of state administrations (police/security forces) in implementing inhuman and often barbaric means to force the poor into locking themselves in, though they have no option but to venture out to survive. They are chased, thrashed, publicly humiliated and even beaten to death for flouting the lockdown norms.

Let us look at a Hindustan Times report on May 26, 2020 during the first phase of the epidemic and the nationwide lockdown. The report states, at least 12 deaths were caused by ‘police excesses’. This year too, in the more ferocious second wave of the epidemic, the saga continues. Even as the union government’s greed resulted in lakhs of deaths, the lockdowns enforced by the state governments (left to deal with the pandemic on their own, as the union government chose to self-abscond) saw the police and administration committing atrocities on the working people, leading to death in several cases. The victims in nearly all the cases are from amongst the working people.

Uttar Pradesh, the epitome of anti-Muslim, anti-Dalit, anti-woman and anti-worker politics, is one of the leading states in this matter. Other than beating 18 year old sole bread-earner vegetable vendor Faisal to death, the UP police are generally having a field time harassing vegetable and fruit sellers, auto and rickshaw drivers and small traders. There are instances of police beating up even the drivers transporting oxygen cylinders or Covid patients in need of medical treatment.

In Maharashtra’s Pune, a 50 year old ambulance driver lost his life at the police’s hand in a similar manner. In Indore, a video of brutal thrashing of another driver became viral. In UP, police have been found to harass health workers on duty as well.

Chhattisgarh’s Surajpur came to news for another such violent video going viral, where the police was mercilessly beating a youth with sticks. In Rehli town in Madhya Pradesh, a woman, who had come out to buy vegetables, was beaten and dragged on the street for not wearing her mask. Other towns in MP saw violence on women as well.

News and videos came from various other states of more excesses and the victims time and again turned out to be not only workers but also belonging to Dalit and Muslim communities and therefore easy prey to criminalization and brutality by the state.

What needs to be noted here is that despite CTUs having control over auto drivers, hawkers unions and other informal sectors, such brazen violation of these workers’ basic rights does not incite solidarity protests and actions from them.

As for the migrant workers, according to a report shared by the Delhi Transport Corporation, more than 14 lakh migrant workers left the city within about a month. This is the data from one city alone. The question about the livelihood of such a massive number of workers during the stringent lockdown overshadows an even larger question about their right to healthcare and nutrition, which so far has not found a very concrete place within the demand sheet and political actions of the trade unions either.

Hanged Between Impossible Choices

On May 25, a twitter campaign hashtagged #TN Workers_Lives_Matter took place on behalf of workers in Tamil Nadu by Thozhilalar Orumaipadu (a collective founded by LTUC, comprising of union leaders, department councils and factory workers).

Why are vegetable hawkers without income when auto/textile giants allowed to make profits? Shutdown all Non Essential Industries and ensure wages for all categories of workers in Tamil Nadu, @mkstalin. #TN_Workers_Lives_Matters pic.twitter.com/h5X8EQ6VAU

— Migrant Workers Solidarity Network (MWSN) (@migrant_IN) May 25, 2021

The campaign voiced the demands of the workers during the pandemic, asking the state government to (a) close factories, (b) provide full wages to all workers (including casuals and trainees), (c) hold talks with trade unions and (d) compensate families of deceased workers (due to Covid) in private companies. A Thozhilaalar Koodam article on the campaign rightly asked: “Why is the government, which is so firm to implement the lockdown, which is letting small shops, vendors, drivers and small time workers to go without work, so confused when it comes to manufacturing sector?”

The campaign echoed the ongoing dispute between the Renault Nissan (TN), Hyundai (TN) and MRF (Puducherry) management and their workers, out of which, Renault Nissan workers have even gone to court and decided to start tool-down from May 26. Earlier, big automobile companies such as Maruti Suzuki and Honda in Gurgaon were closed down, as per demands of the permanent workers’ unions.

While these demands are logical and justified, the question remains whether they reflect the concern and reality of the casual workers and trainees. As was seen during last year’s lockdown, except for a few big automobile companies such as Maruti Suzuki, the casual workers were not paid their wages for the lockdown period, and even the permanent workers went unpaid in many companies.

Between death by virus and death by retrenchment-debt-hunger, the choices that the casual workforce has are no choices at all. Their issues cannot be mentioned simply as tokens in the form of yet another bullet point in the demand list, but must be sincerely fought against. Whereas even permanent workers are unable to maintain their position on tool down during the pandemic, as is already being seen in the Gurgaon belt (Maruti has already opened two out of its three plants and Honda is likely to begin manufacture from June 1), how can the contractual workers with zero support system sustain? Therefore, the question remains: Whose demands are the CTUs mouthing?

Strangulated by Law

It is good to remember at this point, last year’s experiences regarding workers’ wages during the nationwide lockdown. The MHA, on March 29, 2020 cited the Disaster Management Act 2005 (Section 2) and announced that all companies would have to pay full wages to its workers, including contractual workers, for the lockdown period. However, very soon it went back on its own statement once the corporate lobby duly resisted that too-good-to-be-true proposal. “We have to work on the principles of ‘no work no pay’. Our opinion is that organizations should be considerate towards employees and in a difficult situation like this, minimum sustenance pay should be given but where will they get the income to pay? In many countries, the government has shared the wage bill but it didn’t happen in India,” said M.S. Unnikrishnan, Chairman of Confederation of Indian Industry’s (CII) committee for Industrial Relations. Needless to say, even that minimum sustenance pay was not received by most of the casual workers.

The Supreme Court that had initially refused to stay the MHA order on payment of full salary, changed its stance soon enough as well. The number of workers losing their jobs in India during this period crossed 120 million, while many private companies continued to mint profit. The Union government used the outdated and inhuman Epidemic Diseases Act 1897 verbatim, and the Disaster Management Act (DMA) 2005 to take over all powers of policy making, often transgressing the domain of state governments, but neither could legally direct the private companies to pay wages to their workers during lockdown.

The CTUs, though criticized the turnaround by the government and continued to put wage and subsidy demands in their charters, failed to organize the workers and lead any struggle to force the owners and the state to pay wages as industries stopped production.

The bargaining position of the workers as well as trade unions have been further compromised by the dilution of the Industrial Disputes Act into the Industrial Relations Code. The companies are now at liberty to lay-off workers if needed. On one hand, the powers of the unions have been curtailed. On another hand, the threshold limit for lay-off has been enhanced from 100 to 300 workers. Moreover, criminalisation of strike, mystification of the functioning of the industrial tribunals that replace the labour courts, deletion of penalty for associate officers for unfair labour practices and facilitation of fix-term employment have made the unions more toothless.

The CTUs’ role as bargaining bodies, their form of struggle amounting to fighting legal cases in labour courts and tribunals, and some ritualistic token one day strikes have become obsolete in addressing the present attack on the workers through intense contractualization and informalization of economy. With the introduction of new labour codes their traditional role in protecting the economic interest of the permanent workers has been squeezed as well. To address the new reality and attacks on labour by the new economic order, the left CTUs at least need to introspect their politics and devise newer methods of organizing the workers and their struggles. But being controlled by political parties who have already in principle accepted the neoliberal reforms as indispensable there is little hope left.

Still Dissenting

We began with the Black Day demonstration call on May 26 and let us now end with another, albeit less spectacular but equally important, protest by informal workers this week. We know that the Accredited Social Health Activists (ASHA) have been working tirelessly along with other health workers during the entire period of the pandemic. But till date, they are not recognised as ‘workers’ and remain ineligible to receive regular wages, safety kits, health insurance or other facilities. 80 ASHA workers have died of Covid infection in the last one month alone. In protest, the ASHA workers went on a one-day strike on May 24.

The CITU-affiliated All India Coordination Committee of Asha Workers (AICCAW) stated that the strike was successful in 7 states and partially successful in several other states. A memorandum was sent to the PM and the state CMs through the DM’s. In August last year, a similar protest (Jail Bharo) by 6 lakh ASHA workers and other scheme workers took place raising the same demands – which are yet to be met.

Such protests and collective actions give us hope in the power of grassroot movements by workers. The government might cleverly label these workers as ‘volunteers’ and try to wash its hands off their legitimate demands and rights. But the trade unions cannot afford to ignore these struggles as insignificant. They need to realize that the site of politics and struggle are no longer confined to only factories and offices but in most cases outside them. More importantly, they need to truly believe in workers as political beings and not as vote banks as is the general norm. The solidarity to farmers’ struggle is fine, but it will matter in real sense only if the trade unions can revisit and criticize their own dead-end politics and its reformist content.