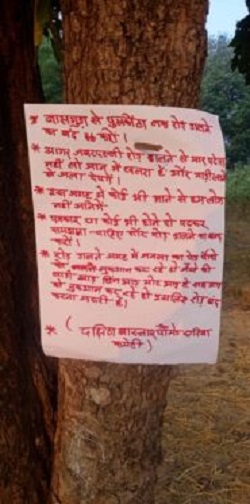

On December 13, 2020, a death threat, to Pushpa Rokde, a journalist, purportedly signed by the Maoist South Bastar Pamed Area Committee, was pinned to a tree near Puskunta village in Bijapur district of Chhattisgarh. The Network of Women in Media, India (NWMI) is deeply concerned about the dire warnings and death threats issued to Pushpa Rokde and deplores all attempts to threaten and intimidate journalists in the course of carrying out their duties.

The NWMI is deeply concerned about the dire warnings and death threats issued to Pushpa Rokde, a journalist based in Bijapur in the Bastar division of Chhattisgarh. The threats were in connection to short-term work unconnected with journalism, as well as in relation to her journalistic work. NWMI deplores all attempts to threaten and intimidate journalists in the course of carrying out their duties.

On December 13, 2020, a death threat, purportedly signed by the Maoist South Bastar Pamed Area Committee, was pinned to a tree near Puskunta village in Bijapur district. In the weeks following its appearance Pushpa sought clarifications about the poster but received none. Nor was there a denial that the poster was not issued by the Committee. The threat was followed up on January 28, 202, with a hand-written note addressed to Pushpa, again purportedly from a Maoist functionary. The note, containing thinly veiled threats, accused her of being a police informer with regard to protest rallies. However, Pushpa states that during the Covid19 pandemic-related lockdown, she was informed by activists about four protest rallies and requested her to cover them as a journalist, which she did.

NWMI has learnt that most newspapers had stopped publishing hard copy editions during the nationwide lockdown imposed to contain the pandemic. The few copies of the e. paper that were being printed could not be delivered to Bastar in the absence of vehicular movement. Due to a common and long-standing practice in Chhattisgarh (and elsewhere), many journalists’ salaries are unfortunately contingent on the advertisements they can secure for the publications they work for. The steep drop in advertisement revenue last year has reduced journalists in such situations to penury. It is an indicator of the enormous financial challenges of being a journalist in rural and small-town India that they are often forced to take up non-journalistic work to sustain themselves.

Pushpa’s precarious financial situation was worsened by medical bills following an accident while she was investigating a police encounter site in Pamed area, where many Adivasi youth had been picked up by the police. Under the circumstances, she was constrained to temporarily take up work supervising road construction works in an interior village, while continuing her reporting for the e.paper.

The death threats issued in December 2020 were in connection with this other work. To date no Maoist group has denied or retracted the death threats issued to Pushpa Rokde.

Given her consistent reporting on people’s issues, the allegation that she is a police informer is not just mischievous, but dangerous in a polarised conflict zone such as Chhattisgarh, where Maoists have meted out brutal punishments to people assumed to be ‘police informers’. Apart from killing journalists like Sai Reddy and Nemichand Jain in Bastar in 2013, Maoists have killed villagers and contractors suspected of being police informers. The latest such incident in Chhattisgarh took place on January 26, 2021.

Pushpa Rokde’s exemplary journalistic work

Over the past decade, Pushpa has been consistently reporting on police atrocities as well as local issues and problems faced by the Adivasi villagers. She has faced the wrath of the administration for many of her stories. She has reported on issues related to jal (water), jungle (forest) and zameen (land) – critical to Adivasi life in Chhattisgarh.

Pushpa has highlighted villagers’ opposition to the setting up of paramilitary camps in the interiors, their protests against roads to facilitate iron ore mining projects, and their opposition to mining due to both environmental destruction and denial of compensation for land acquired from local residents. She has also reported on cases of sexual assault by security forces.

Pushpa’s people-centred reporting on Adivasi rights stands out, as does her willingness to speak up for human rights. On several occasions, upon receiving information about police crackdowns in villages, she has investigated the matter, with her work sometimes leading to the release of innocent village youth from police lock-ups.

While the controversial draft Chhattisgarh Protection of Mediapersons Act, circulated in December 2020, aims to allow broadly defined “newsgatherers” to carry out their work without fear or repercussion, for local women journalists like Pushpa Rokde, who live and work in the area, this is a distant dream.

The NWMI stands in solidarity with Pushpa Rokde and supports her determination to continue to tell untold stories from Bastar.

- The NWMI strongly affirms the right of journalists to report freely and fairly. Independent reporting is in the larger interests of ordinary people eking out a living under the shadow of armed conflict and journalists must be protected so that they can tell their stories.

- The NWMI urges media houses in Chhattisgarh to collectively work towards protecting their journalists in every way; strengthening their financial condition and providing job security is a crucial step towards enabling them to work freely and without fear or favour.

- The NWMI also demands the immediate cessation of threats and intimidatory tactics from all state and non-state agents – and those associated with them– that put undue pressure on journalists and others, who are vulnerable to such attempts at intimidation.

The Network of Women in Media, India

February 4, 2021

The statement was originally published at

https://www.nwmindia.org/statements/reporting-from-bastar-challenges-for-a-woman-journalist/