Abanindranath Tagore’s ‘Nalak’ is a classic in Bangla literature. Translating a classic can be daunting. But the task was taken up by Urbi Bhaduri and the English translation was published by Niyogi Books a year back. The translated book remains reverent and true to the original, and yet stands its own solid ground and perhaps even surpasses the original publication in some ways. Soulfully illustrated by Nikita Gandhi, ‘Nalak’ is a book to quietly spend time with, and feel it grow within oneself. Writes Madhushree.

Nalak

Abanindranath Tagore

Translation: Urbi Bhaduri

Illustration: Nikita Gandhi

Publisher: Niyogi Books

Date of publication: June 2019

The book

Do we choose books, or, do books choose us? I could have said that Abanindranath Tagore’s Nalak, translated in English by Urbi Bhaduri chose me, if not for the fact that I received the book in a rather predictable manner. It came to me neatly packed by a courier company, purchased and posted by a friend, who had read and liked the book and made it a point that I read it. I’m going back to this little history in my mind as I recognize, now, that even though we – the book and I – did not run into each other in an obscure bookshop on a rainy evening, there was something a little magical about the care and intention of sharing which was involved in the entire process through which it arrived at my doorstep. Well, caring and sharing are also integral to the content of the book, which is based on Buddha’s life. And it was heartening to find out, as the book began to speak to me and I in turn began to speak to its makers, how these features were scattered all over the process through which the book was created.

Not only did I not choose the book, I was wary of it. Nalak is a children’s classic in Bangla, or rather, a classic meant for children though read more often by adults, except perhaps for children of a certain bent of mind and heart. Either way, translating a classic can be daunting. What if it overstates the original? Or dilutes? Moreover, even if we consider Urbi’s book primarily for those who have not read the original and hence do not have a reference to compare it with, the content of Nalak can be seen as dated: a simplified version of Buddha’s life that perhaps hardly add value to the information bank possessed by today’s English-speaking school-goers, or by adults like myself. The worst part for me was that I had never really liked the original book. It depicted Buddha’s life, partially through the visions of a young devotee named Nalak, who kept pining, ironically, to see Buddha for once with his own eyes (and not the spiritual eye) throughout the book. As a child reader, I did not relate to Nalak’s pining at all. Compared to Buddha, Nalak’s life was quite undramatic and insignificant, so one did not know why the book was named after him in the first place, or what he was really doing in the book. Other than having visions, all he seemed to do was leave home and come back, without having achieved his desired feat.

The text

So I had my blocks about the book. I evaded it for months – even managed to lose it once, in the middle of the lockdown, during which the body, the mind, the memory – each with its virtues and vices formed a life of its own, none of which had anything to do with me. The six realms of samsara were being staged all at a time in strange ways in our everyday life – the money-hoarder gods at the brink of a system collapse, the hellfire, the terror all around; troubled times.

But when I finally found and began to read Urbi’s Nalak, accompanied by Nikita Gandhi’s illustrations, which I adamantly chose to dislike at first glance, the book grew on me. I can perhaps say that I discovered Nalak for the first time in my life. And Urbi’s language has a role to play in that. The words flowed effortlessly, without drawing attention to themselves. Although Urbi’s writing stayed painfully true to the original text, they sang their own chant. She says, as she read and reread Abanindranath’s Nalak during her childhood and adulthood, during difficult times, “Each word was an anchor, each word a bead in this whole mala, to be counted, examined and understood. It was as if my life depended on grasping the meaning of the Buddha’s teaching.”

One can feel it in her rendition of the book.

I reread Abanindranath’s original book after I finished Urbi’s and I could somewhat revisit what I had against it (and still do). While Abanindranath’s language was extremely endearing, there was something preconceived about it, as if the author knew how the reader would, and should, react to his words. An aged and learned grandfather speaking to the grandchildren in a slight ‘baby-voice’. Whereas Urbi’s Nalak – her first translation work that she finished in 2005 (she is in her late thirties now) – spoke to me in a friendlier tone. As if it was looking for the essence of the book along with me, not leading me to it. And the best part was that I finally understood why the book was named after Nalak. The book grew within me, and I grew along with it, as Buddha grew in his spiritual journey, and Nalak grew up through the various stages of devotion: from intense longing to the realization that possession of the ‘object of devotion’ is achieved only when one is free to let it go.

Not that I had an apathy towards Abanindranath Tagore’s writing. On the contrary, I loved some of his other books for children and young adults, Khirer Putul, Raj Kahini and others. But the reason behind my guarded reaction was that Abanindranath, like the other illustrious male Tagores in the family, was a grand institution in himself. Even if his authorship was omitted from a text, one could recognize his style. Nalak was for me a product of that institution that sweetly prescribed to me how I should perceive the philosophical world of Buddha. Can philosophy be imposed without leaving space for one’s own questioning? Urbi’s words saved me from that sweet but dictating prescription and that was needed, especially because the book is primarily philosophical, not just any novella – a difficult book that way.

The visual

However, I also suspect that even more than the original author, I blame the illustrator of the original book that I read for my apathy. Just as I know that Urbi’s book wouldn’t be the same to me if not for Nikita Gandhi’s drawing after drawing of silhouetted mounds of figures – refreshingly liberated from the burden of trained skillfulness – placed against dark, scratchy backgrounds, that grew on me as much as the text as I read on. Which is why, as an amateur illustrator myself, I’m tempted to spend some time on the two Nalaks and their illustrations.

What I said about Abanindranath Tagore being an institution could also be said about illustrator Krishnendu Chaki, who, in his promptly recognizable style, decorated the original and surely the most circulated version of Nalak published by Ananda Publishers in 1986, decades after Abanindranath’s demise. When I’m accusing the original Nalak to be dictating my reading, and my feelings, it is not only Abanindranath but the Tagore-Chaki duo that I’m addressing. A book-cover often creates a first emotional impression about the book, especially in a physical copy, and that impression often lingers in our mind when we remember the book. Nikita’s cover introduces Urbi’s book by setting a very personal mood – immersed, dark, mystical, scratchily complex, but also establishing Buddha as the centre of inner-strength and peace at the heart of the meditating devotee. Krishnendu’s well-remembered cover, on the other hand, introduces Ananda’s Nalak by its bright colours, confident but ephemeral lines, impersonal human expressions, and a distracting composition of scattered but way too well-defined geometric partitioning of multiple incidents from Buddha’s life. It does not invite the reader to stop and contemplate, which is a pity, since the book demands exactly that. Moreover, by completely evading even a symbolic presence of Nalak, Krishnendu’s cover fails to usher readers into Nalak’s world, to explore how the author perhaps placed himself in Nalak in the text, and expected the reader to do so as well. His dyadic post-production interpretations did not even make one curious about the process of the text and the illustrations coming together, which Nikita’s cover and illustrations do.

The gender

One should surely acknowledge that two renowned male artists living in two different generations, decades apart, are bound to have a different quality of relationship compared to the two fairly unknown (though deserving to be known) women artists living in the same time and space. The gender appears in Nikita’s untrained but engaged drawings in interesting ways, combined with her experience in exploring craft with children and working in Adivasi regions. Her Yashodhara, as Prince Siddharth abandons her along with their son in the middle of the night, is the primary frontal figure in the corresponding image, unlike in popular representations including Krishnendu Chaki’s. Her visualization of Nalak’s mother shows her looking away from the path taken by her son – choosing the aged Debal Rishi over her. Though she dutifully repeats the words that just shattered her world: ”I worship the Buddha under the pure sky; I worship the Buddha with my beautiful [Nalak] flower,” Nikita’s interpretation of the scene immediately evokes a surge of mixed feelings: why should she worship Buddha? Who is the Rishi to tell her what her feelings for her son should be? The image complements the text that deprives Nalak’s mother of such thoughts, as if they have no place in the emotional map of the narrative. But in the end when Nalak returns, he and an unknown beggar stand in the same vertical line in front of his mother’s house, waiting for her to emerge out of the hut: this image came to me as an apology, almost as an attempt to make up for the unspoken emotions of the abandoned mother – not only Nalak’s mother, but all the women abandoned by the holy men scattered in the religious texts.

Nikita’s Sujata and Punna are not the curvy-figures, sharp-featured women they have been otherwise established as; they are rather solid and dark like the men. Solidity is a feature in Nikita’s art. Even her close-up picturization of the wounded goose at Prince Siddharth’s feet is so solid and real – makes one halt and linger, while also remembering its stark difference from Krishnendu’s drawing of the same scene – a beautiful composition, but of a very different nature.

Going by the illustrations inside the books by both artists, which hold onto the same mood as their respective book-covers, I stand by the note of impersonality of Krishnendu’s drawings that I spoke about, not only in comparison to Nikita, but also compared to other artists illustrating Abanindranath Tagore’s works such as Nandalal Bose (Buro Angla, Signet Press), Satyajit Ray (Raj kahini and Buro Angla, Signet Press), Ashish Sengupta (Khirer Putul, Ananda Publishers) etc. Gender is therefore not the sole determining factor in this stylistic comparison. Nikita’s drawings are, however, indeed different from all these genres; one can even say that in this book she is drawing the same thing over and over again, rubbing, scratching, lingering. The goal seems not narrating, but calmly creating a harmony with the unhurried text, which is open to questioning and understanding. Nikita’s nocturnal silhouetted figures have no faces and yet they are personal because, as she intended, they leave space for the reader’s imagination.

The spiritual

The making of Urbi and Nikita’s Nalak has part of its roots in the makers’ own engaged spiritual practices as well as professional practice around caregiving and facilitating. Both have worked with children and youth from marginal communities over years, in an attempt to enable them through creativity, but also in return enabling themselves, in an attempt to find a path from ‘dis-ease’ or ‘dis-order’ to ‘recovery’. Their searches might have found a common string in Buddha’s own search.

Nikita’s illustrations came after Urbi’s book was finished. But once they began to work together, simply based on the fact that Nikita’s work had struck a chord in Urbi’s heart, it was a co-creation through mutual ideation – not free of frictions but always coming back to an intent of reaching out, recovering, harmonizing, and at times, handholding. As they both say in different ways, “We found a perfect resonance in each other’s work”. I wonder if it is possible to do justice to a book like Nalak without exposing oneself to such emotionality. After reading the translated book followed by the conversations with both the makers, it is difficult to ‘evaluate’ it, to separate it from the combined effect of Urbi’s search for “finding my [creative] voice” and Nikita’s search for “what drives me as an instrument [to create].”

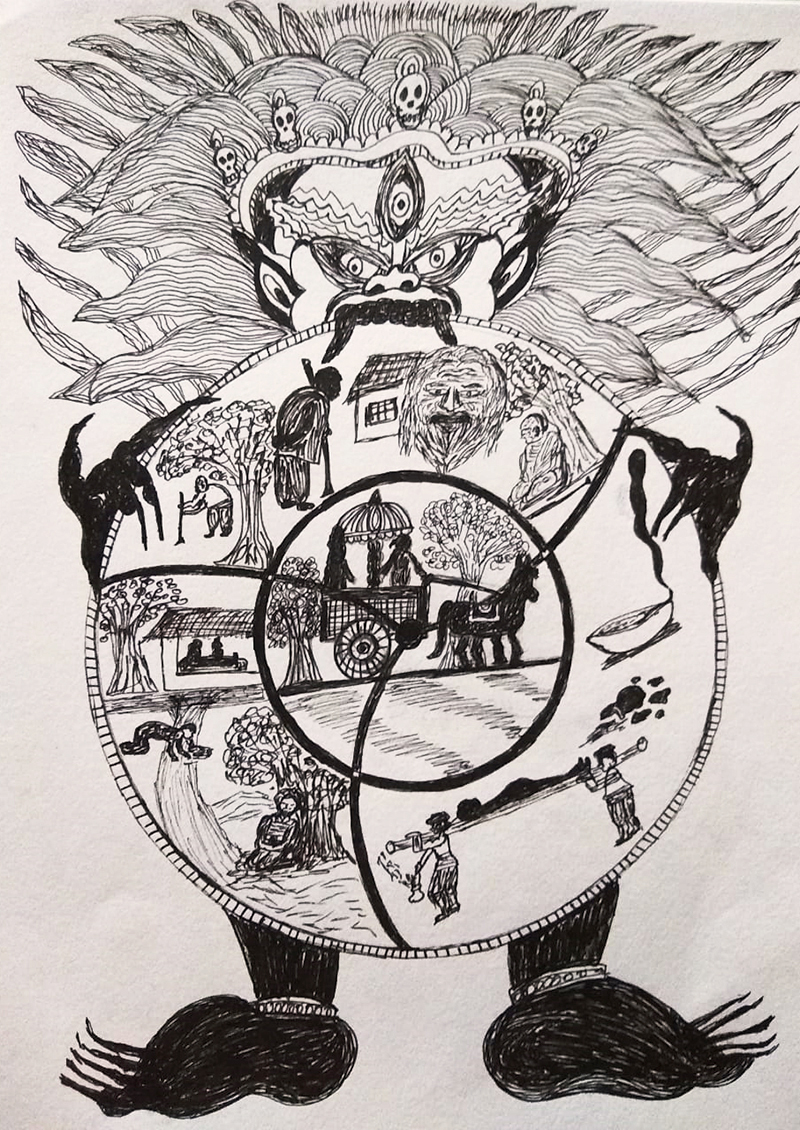

I cannot avoid once again delving into the interrelation of text and illustration in the context of how the book demonstrates their engagement with the Buddhist spiritual symbolism. A stunning image from the book comes to the mind: Siddharth’s realization of the four noble truths by witnessing the miseries in life. In the makers’ shared imagination, the Bhavacakra (Wheel of Life) not only depicts this scene, but also makes one wonder, if Buddha was truly the artist-designer of the very first Bhavacakra as some stories claim, could this truly be the moment Buddha the artist got his inspiration from? For designing something that would later become one of the most popularly used symbols in spiritual practice across the world?

Another such image depicts Mara’s attack on Buddha. While a Tibetan book of culture played as a reference to Nikita’s imagination, her choice of placing the figure of Buddha on Mara’s black salivating tongue couldn’t have been better suited to Urbi’s urgent words: “There was no moon, no starts overhead; only the great nothingness, great darkness! It was as if something was rushing to engulf the earth with open jaws…”

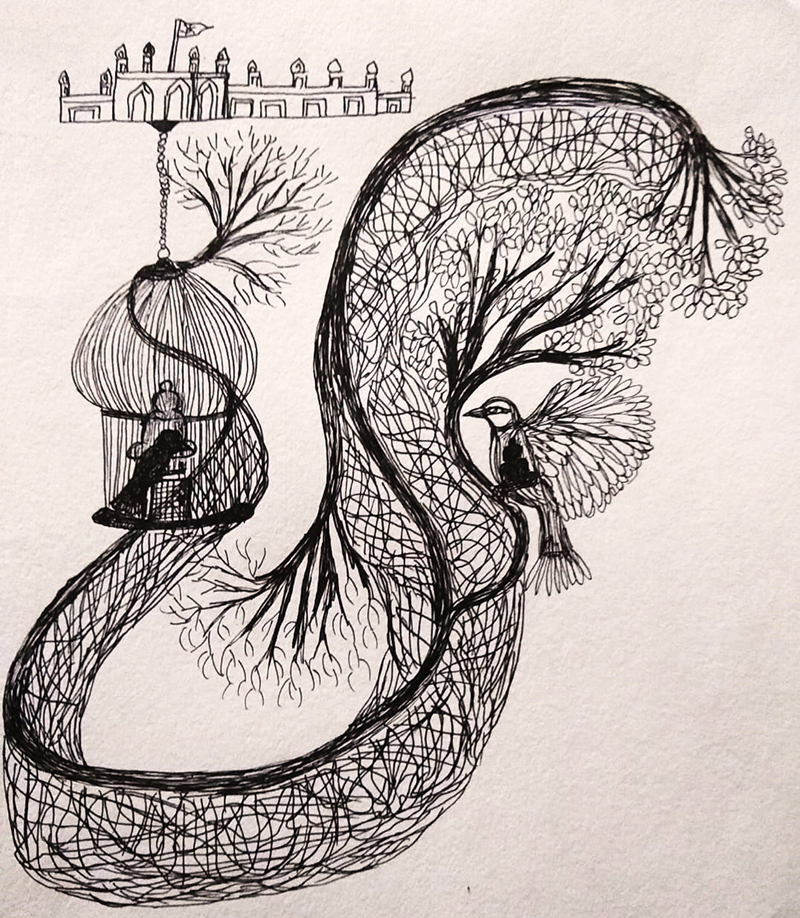

The third symbol that has remained with me is an image that we briefly spoke about earlier. It shows Nalak’s hands, floating the lotus in the river, just before missing his heart’s desire one more time. It is special not only for the powerful simplicity, but also offers a closure to a visual saga that opened up when the wounded goose fell in front of Siddharth’s feet. The two lotus-feet and the lifeless goose commenced Siddharth’s journey; that image valued our need of holding onto life. The hands floating his lotus-heart into the river ended Nalak’s journey; the image value our need of willfully letting it go.

The growth

I feel – Nalak has brought out the personalities of Urbi and Nikita. But it does not stop there. There was a common statement that both of them made at different points in our conversations. They said, they grew while working on this book – as artists, as humans, as collaborators. As I caress my own moments of growth as a reader of this book, I remain curious as a practitioner interested in the process of collaborative art-work and artistic interaction with the youth. Curious about, how today’s English-speaking Indian young adult readers would react to this very silent, unassuming book, given the smart, chattering alienation of the consumerist self that society is constantly caging them in.

Acknowledgment: Thanks to Vartika Poddar for the book and discussions.

…

The reviewer is a dancer and an illustrator.

Feature image: Nikita Gandhi (Debal Rishi and Nalak leave while Nalak’s mother weeps)