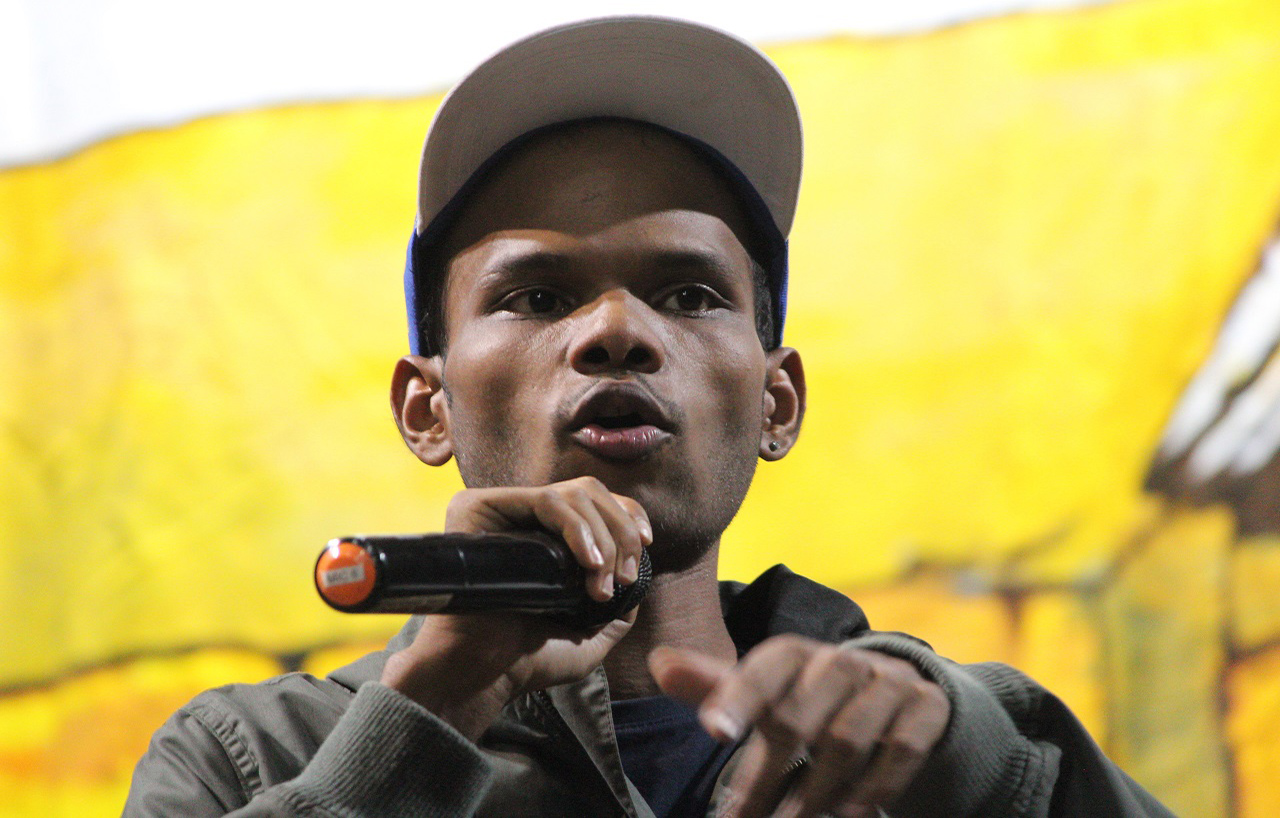

Sumeet Samos, a rap artist from Odisha and an Ambedkarite activist was in Kolkata to perform at the People’s Literary Festival organized by Bastar Solidarity Network (Kolkata Chapter) on February 29. Utsa Sarmin talked to him on behalf of GroundXero about his activism, politics and journey from a remote village in Odisha called Tentuli Pada (basket full of tamarind) to becoming one of the most sought after young Dalit artists in India.

Why do you use rap as your artistic form?

When I was a part of the activism circle in JNU (Jawaharlal University, Delhi), I realized that the outreach through writing articles or through speeches is not as potent. So you have to reach out through some creative medium. Along with that, I had some inclination towards certain Dalit art forms from back home. I wanted to use popular language to communicate my political articulation and that cannot be done in academic articles or presentations. Popular language can only be used in creative mediums. That’s why I rap. Writing articles can reach 200 people but putting up a Youtube video of raps can reach 10,000 people. Hence I chose to rap.

Can you tell us something about your journey from Koraput district in Odisha which is regarded as the most “backward” district in India to JNU which is considered as the most elite institution in India?

There was always a lot of uncertainty in this journey. I never knew what I was going to do next because of the absence of guidance and support system just like many Dalit students from lower-middle-class families and poor families face. But the aspiration to study at a big university was always there. I know that my ideas, writings, will be accepted and validated if I have education. The idea of acceptance by the society pushed me towards education. My mother also encouraged me and few people from back home would always talk about what it means to be educated. That encouragement was always there. I was never exposed to any anti-caste discourse or any “radical left” discourse although I grew up witnessing a strong radical left movement but I could not articulate it. JNU happened to me out of pure chance. I did not have any other options. That was the cheapest and most affordable university to study at. Someone told me about it and I applied. Before JNU, I used to work in call centers and hotels.

How would you describe the role of JNU in your evolution as an artist?

I actually started writing after completing my course in JNU. The trigger was Rohith Vemula. I started writing about my personal experiences after Rohith’s suicide. There were many Dalit students who were also writing about their own experiences of being Dalits. I started interacting with them, especially in JNU. There were some PhD students who advised me to read some basic literature by scholars like Gail Omvedt or journals like Roundtable India. All of them helped me form a language for my politics. They gave me a political framework which was not rigid. Even within that framework, there were a lot of debates. For example, a Dalit from Tamil Nadu, how that person understands anti-caste politics or the politics of nationality varies from how a Dalit from Uttar Pradesh will understand anti-caste politics. That will again differ from how a Dalit from Telangana will understand the same politics as it has a radical Dalit-left movement. The question of caste Muslims and gender were also present. These debates helped me formulate a language over a period of time.

What was the first rap that you wrote?

I don’t exactly remember my first rap. It was about me being a Dom. What it meant to be a Dom? I was in JNU. It was the end of 2016. A lot of things were happening. I used to attend a church in Delhi. I had a large group of middle and upper-middle-class Christian friends who studied in good colleges in Delhi. I also had friends in JNU who came from Bihar and Rajasthan. Most of them are bhumihars or Rajputs. There was a certain sense of exclusion when I was with them. Either I wasn’t able to fit in their everyday life, conversations, lifestyle or they are failing to cope with me. I was also struggling with my studies and financial responsibilities at home. So there was an existential crisis. At times people would speak harshly to me or belittle me. This was piling up. One day I just looked up at the sky and started ranting. After I came back to my room, I recorded it on my phone and uploaded it on Facebook. Next morning, 10,000 people watched the video and 60 or 70 people messaged me on Facebook saying this is Dalit rap. That is how it started. Many incidents pushed me to rap. Not one specific incident.

In the last few months, you have been performing more and more on the politics of hate, against NRC, CAA. Does this represent an evolution of your work as an artist?

Yes, definitely. I think both go hand in hand. For my art to flourish, my politics also have to evolve. I get a lot of opportunities to go to different places, like, I spent one month in Kerala where I performed in more than 40 events. Then I went to Tamil Nadu, then to Karnataka. And before that, in Delhi, wherever I got a chance, I made sure to speak out or perform. In all these journeys, I got to meet a lot of people, and heard new narratives which I never heard when I was staying in Delhi. These somehow shaped my articulation which translated into my rap. I had never rapped about anti-Muslim violence in particular. But once I got this confidence and these narratives concretized in my mind, I started doing it. I wrote a song called “Babri to Dadri” where I talk about Babri Masjid demolition to Akhlaq’s lynching and how the history of anti-Muslim violence by Indian state has been continuing since 1992. So yeah, my political and artistic evolution go hand-in-hand.

Most often, your songs/numbers are a mix of Hindi and English. Why have you chosen these languages? Do you ever write/perform in Oriya?

I use English to communicate with the university and college-going crowd. I also came from student activism. The university and college students form a big part of my audience. English breaks the language barrier across the country. Apart from that, I use Hindi because in North India there are a lot of Dalit youths who are not part of these universities and colleges and do not know English. You have to use Hindi as a medium to reach out to them. I have performed in Odiya also especially in villages, in panchayat level meetings and gatherings in Odisha.

How do you situate yourself within the Odia Dalit-Adivasi literature’s tradition of protest, especially if we think of Basudev Sunani, younger poets like Hemant Dalpati?

Odisha is very special when it comes to Dalit Adivasi art forms because it’s one of the very few places in India where you find the shared art forms especially in Southern Odisha, where I come from. There is a dance form called Dhemsa, a festival called Chait Parab, a cultural identity called Besia. Then there are certain instruments which are common to certain tribes in Southern Odisha as well as to the Dom and Pana community. That shared association and shared art forms have always been there. That is one legacy that our ancestors have left behind which I carry forward. Since I grew up in a village, a very traditional village in Odisha, my experiences were as grounded as possible. I didn’t have to read them (Basudev Sunani, Hemant Dalpati). But once I started reading them, I felt I was reading about my own village. I think they have let it out as truthfully as possible. The only difference in my place, where I come from is that there cannot be a large scale caste violence because we have a majority tribal population. 50 per cent of the population is tribal and 24 per cent Dalit. To mobilize each group against the other for caste reasons is very difficult. Both communities are struggling because of corporate interventions like Hindustan Aeronautics limited. The lands have been snatched from Adivasis. Dalits don’t have lands. Hence mostly what can happen are state-led atrocities and displacement and few small scale caste violence. That is one history that is different from other parts of Odisha. Practices of untouchability, segregation, ill-treatment- all are present. But caste-based violence usually happens in Western and Eastern Odisha. In Kerala for example, there is a lot of caste-based discrimination but not large scale violence but then in places like Telangana, Tamil Nadu, you see violence.

You are one of the younger artists who use digital space extremely skillfully. Can you comment on the politics of the digital space as a Dalit rapper? What has it meant for you?

I think it is a very difficult question because I really don’t know how to grasp digital space and its impact on mass-based protests. I can only say that it can be used to mobilize people in a very efficient manner only if the youths from slums, small localities are a part of this space. Otherwise, the digital space we use, being part of cosmopolitan cities, being part of universities, most of the time, is just an echo chamber where you meet similar like-minded people with little differences. So I don’t see much impact of digital space. But what it can do is popularize certain marginalized discourses. For example, till yesterday, people like Kunal Kamra would have never talked about caste but suddenly he will come and say, “oh now I remember Rohith Vemula.” I don’t know how truthful he is, but they are bound to speak now. Or let’s say Swara Bhaskar who will come somewhere and start talking about Dalits. Maybe because that is the compulsion of the time. Digital space has created a huge role in pushing certain marginalized discourse in the popular domain. But this space doesn’t have the power for real transformation. People like Swara Bhaskar, Kunal Kamra or other social media influencers, they have millions of followers but if you ask them to give one call to bring 500 people on the street, they cannot because they do not possess the language to communicate with masses from the ground. For that, you need ground networks and use the popular language of those places. I think people can use digital media for both pushing forward certain discourses in popular space as well as mobilizing but that has to be rooted in the ground. That has always been my aim which is why I wanted to go to villages in Tamil Nadu or Karnataka where I meet a lot of local Dalit community people and get to know how they think, what do they think about Chandrasekhar Azad or Dalit politics in general, what do they think about Ambedkar, land, Tamil identity, Periyar. All these debates at the local level are very interesting. That is not something one can really grasp just through social media activism or digital media activism.

What are the challenges for a young, independent Dalit rapper/artist like yourself?

Personally, I have tackled some challenges due to my privilege of studying in a university and the networks I have built. I get some projects here and there and I get to write some articles through which I earn some money. I also get to perform internationally, like in France or Switzerland, Mauritius. I even get support from the community. In terms of political challenges, I have evolved. Even a year ago, I used to be very intimidated by being undermined by people. Now I am not because I have confidence in the topics I speak about. I have started reading a lot of literature, started interacting with people. Now I have built confidence and I know what I speak about. There can be debates in terms of perception but the truths cannot be challenged. Of course, there are some people who look down on me. They make fun of me. Those are part of activists’ life. I don’t think anybody should make a big deal out of it. That is something the liberals usually do and I don’t like that. Trolling is very common. In places like Niyamgiri, Chattisgarh, or like Tamil Nadu, Dalit Adivasi activists get detained or arrested overnight without saying anything. But for these liberals, someone commenting on Facebook is becoming a huge issue. So I do not pay much attention to that which I feel is a very self-obsessed politics where you make everything about yourself and not about the real issues.

Who is your intended audience? How is the politics of caste reflected in your relationship with your audience?

I have two kinds of audience. First is the university students and Dalit Bahujan or progressive student organizations who invite me to perform. Most of them are aware of the discourse that I speak of. But many of them are not. When the audience is acquainted with your politics, it is always a smooth run. But the people who are not aware, they have curiosity, they have some questions and they always engage with you. The second kind of audience is the popular audiences like in literary festivals or protest gatherings where you have a lot of working-class Dalit Adivasi or Muslim protesters. For these spaces, you have to make sure that your academic learning is transformed into popular language. When I rap in front of them, I always have this little bit of anxiety as to how they would respond because I am talking about issues like caste, fascism, Modi and Amit Shah, media being sold out, solidarity of the oppressed sections, land grabbing, Babri Masjid, Dadri lynching, untouchability, caste supremacy. So there is always a question of how they perceive it. It has different tangents in different places. In some places, people accept you wholeheartedly and they like what I speak about and in certain places, they also have questions. So either its acceptance or questions. I usually refuse to go on commercial platforms because I know people come there to drink and chill and I am not going to talk about untouchability and pain and suffering and corporate loot and caste in that space. If I know there is a risk of performing in that kind of place, I never go.

Rap is not a very popular form of music among the masses. So how do you make them connect with your music?

I will give you a little example. In Kerala, I performed in front of around one lac 80 thousand people recently. Most of them were working-class Muslims. Then I went to Tamil Nadu where most of the audience were working-class Dalits. Now they are hearing rap for the first time. That is a new genre for them. So when I perform, I make sure to summarize the points before rapping so they get a gist of what I say. One cannot compromise with certain facets of rap like the rhythm or the pace or how you utter the lines because sometimes you have to shorten the lines. Therefore the message doesn’t get conveyed to the crowd some of the time. That’s why I always explain the message so that they understand. Also, in between songs, I raise some political slogans. A Muslim audience has heard slogans like “Modi-Shah tera naam Islamophobia” or “NRC tera naam Islamophobia”. I give these slogans. If I go to Niyamgiri or Koraput to perform, I talk about the identity Desia and that we are working-class masses, we are sons of the soil. When I say these to them, they relate to it and then I start my rap. You have to give them some point to relate to and you have to know your audience and what they relate to. That’s what I always try to do. I also talk about local icons. When I go to Telangana I talk about Kalekuri Prasad; in Odisha, Laxman Nayak; in Chattisgarh, Soni Sori and the struggles in Bastar, Naraynpur. I think it is always about making people relate to your art. Once you reach a site, you see the banners, you converse with people and you have to pick up its essence. That is a very interesting thing about artists. This is what Modi (Narendra Modi) does. Politics and art go together. Both are theatrical and you are performing. When Modi goes to Banaras, he says, “I didn’t come here because I wanted to come. I came because Ganga ma called me.” Now “Ganga ma” is very close to the hearts and minds of Banarasi Hindus. He goes to Assam and talks about Assam tea. The middle-class population fell for that trick. No matter how much we make fun of Modi, people actually relate to him. I feel today’s urban-centric activist circle have failed to do the same. They do not relate to the masses. You cannot talk about the anti-fascist struggle against Modi and Amit Shah without relating to the masses and their local sensibilities. If you go to Dalit Christian circles in Tamil Nadu you can talk about Immanuel Sekaran, or in Telangana, there are a few Madiga Christian activists who have been part of anti-caste and radical left struggles against land grabbing. Now when you go to perform there, you have to remind the masses of these activists. Tell them about those struggles otherwise why will they listen to you? You cannot just speak about some centralized hero.

What do you think about corporate literature festivals, especially the ones organized by mining companies? What is the role of independent literature festivals like PLF, in this regard?

The festivals funded by mining companies are paradoxes because you go and displace the tribals, take away their land and push them to precarity, slums and then after all of that, you invite one Adivasi writer in these festivals and ask them to talk about the Adivasis. This is like what Malcolm X said, “If you stick a knife in my back nine inches and pull it out six inches, there’s no progress.” So those festivals are like that and the spaces are very exclusive. They are only for the elite, sophisticated English speaking mass. I was at the Mathrubhumi Literary Festival in Kerala. It was not organized by any corporate organization but by bookstores and newspapers. They asked me to perform and I did. But during the dinner where they invited us, I saw Surendra Chowdhury, Shashi Tharoor, Jayram Ramesh, even Abhijit Banerjee, Sagrika Ghose. There was a big fountain including fine dining. I left. It is so shameful. In the morning you talk about marginality and poverty of marginalized people and in the evening you have lavish dinner. On that note, I think autonomous independent literary festivals are important. In those festivals, real people-writers, activists, artists-who are working among the masses can get some space. Director Pa Ranjith organizes Vaanam arts festival in Chennai. He makes sure that performers are from lower middle class or poor Dalits and tribals and he invests money on them. During the festival, there are bookstalls, food stalls, and art stalls installed by them. I think that is truly democratic. It will take a long time but we need more of these festivals.