In this essay, the author Aniruddha Dutta, explore trans-queer community spaces far away from the metropolitan cities, their relative invisibilization, and discusses their purposes, their histories, and highlight the often unacknowledged labour behind their sustenance.

The last months of the previous decade ended with a flurry of LGBTQIA+ pride walks in not just metropolitan cities like Kolkata and Delhi but also smaller ones like Siliguri. Urban pride walks have been marked as vanguards of social change, paving the way for the rights and social acceptance of people marginalized for their gender/sexual identities. The spread of prides from bigger to smaller towns in the 2010s seems to signal the expansion of progressive ideas from metropolitan cities to seemingly more ‘backward’ places. The last decade was also marked by a proliferation of queer social spaces in cities like Kolkata and Delhi, paralleling the growing visibility of queer and transgender people and related issues in the media and public sphere [1]. Kolkata, for example, now has two “cafes” catering to trans-queer people and their allies: Amra Odbhut Cafe and Cafe #377. Amra Odbhut has been hailed as the only community space of its kind and as a pathbreaking example of resistance to socially imposed gender/sexual norms and identities, while Cafe #377 has been celebrated as a sign of the growing liberal acceptance of LGBT people in Kolkata. Metropolitan spaces and events gain their distinction by virtue of their supposedly pioneering forms of progressiveness, showing “how far metropolitan India has come” in contrast to the implied conservatism of surrounding peri-urban or rural areas.

But the distinction and vanguard position accorded to metropolitan prides and cafes depends on the relative invisibilization of many other queer spaces and events, some of which have been operating for much longer than their metropolitan counterparts. A relatively neglected development in small towns and rural areas of West Bengal over the last two decades is the growth of formalized spaces, known by various names such as ‘drop-in centers’ or ‘shelters’, where people of marginalized genders/sexualities may take refuge from social discrimination and violence, and build their own communities and movements. Sumi Das, transgender activist and member of Moitrisanjog Society, a collective that has created such a space in a village in North Bengal, says: “news about shelters or drop-in spaces like ours doesn’t get reported often in the media… we want people to know that there are such shelters outside big cities, that people of marginalized gender and sexualities have built strong communities in these areas.” These spaces have evolved from informal meeting spots in parks, railway stations, or houses of local trans/queer people, and have grown further through diverse sources of support, including donor agencies, local community contributions, and even political leaders. Like their multifaceted history, they are used in multiple, flexible ways – for fun, gossip and self-expression; for community events, cultural performances and workshops; for shelter during emergencies. Indeed, they perform crucial functions like crisis prevention and political mobilization among gender/sexually marginalized people, even helping to resist fundamentalism and communal polarization within trans-queer communities.

In this essay, I explore some of these spaces – their purposes, their histories, the communities that use them – and highlight the often unacknowledged labour behind their sustenance. While similar spaces exist in various states of India, I focus on West Bengal based on my experience as a researcher and community member who has frequented such spaces in the region for over a decade.

Sheltering diversity

Let’s start with a recent example. A few months ago, on the 15th of August 2019, a rather unconventional club was opened at Kanchrapara, a small town in the district of North 24 Parganas to the north of Kolkata. Located in a small building that was previously used for meetings by local senior citizens and then abandoned, the club is meant as a gathering space for LGBTQIA+ people, especially people from the local kothi-hijra communities (a spectrum of feminine-identified persons usually assigned male at birth). Though the club largely escaped media attention, Banti, a kothi community member from the area, reflected on its importance during the inauguration: “kothis face a lot of harassment and abuse, but because of this, we are getting a lot of support… we can have gatherings and performances here… the respect we get will increase… people will see that we, too, have our own space and organization” [2]. The club came about as a result of the efforts of Silk Roy Chowdhury, a transgender/kothi activist and member of Nadia Ranaghat Sampriti Society, a non-profit collective of largely working class and Dalit trans-queer people based in the area. Silk teamed up with Mousumi Saha, a guru or leader of the local hijra community who is affectionately known as Mousumi Ma or ‘mother Mousumi’ to community members, and approached a local political leader who gave them access to the space. Mousumi Ma donated funds for repairs and furnishings. The space is meant for a spectrum of transgender and queer people, reflecting the diversity within kothi and hijra communities, which can include feminine males, those identifying as women or as third gender, and people with fluid gender expressions. As Mousumi Ma explained to me, “I have some chelas (disciples) in bhorokti (feminine attire), some chelas who are korpeshiya (male-attired)… I thought I would leave something behind for both!”

While the Kanchrapara club is new, Sampriti members have operated a similar space in the small town of Ranaghat, north of Kanchrapara in the Nadia district, for over a decade. Two rented rooms in an old building near the Ranaghat railway station have served as a drop-in center cum temporary shelter for the local trans-queer community since 2009. The space is modestly furnished with plastic chairs and a mattress; an excerpt from the Indian constitution and a poster of LGBT terminology in Bengali are framed on the walls. Like the Kanchrapara club, this space too caters to a diverse range of people of varying gender expressions and ages, who gather here to socialize, find emotional support and belonging. A teenager, who self-identifies as both gay and kothi, is disturbed by her ongoing relationship with her parikh (boyfriend). She comes regularly for counseling to Bikash, a kothi elder who prefers male attire but is known as ma (mother) because of her care and mentorship to generations of the community. Bikash has a variety of ‘daughters’ – some are kodi (male-attired), including gym-toned gay men who become ‘sisters’ to each other within this community space, while some are bhorokti (female-attired), such as Ankita, who can wear sarees and dresses only in the shelter due to family opposition. Others mix kodi and bhorokti styles. The place thus fosters self-expression and mutual caring for people of varied gender and sexual expressions. Besides the kothi-hijra spectrum, lesbian women and transmasculine people have also begun coming in recent years. As Bikash says, “the important thing is to welcome everyone.” Of course, this is not an ideal or utopian space: there are petty conflicts over parikhs or over seniority and rank within the community. But in a context where queer communities have often become siloed on the basis of identity, status and respectability – for instance, many gay men distance themselves from gender non-conforming people; some transgender women distance themselves from hijras – a space that has sustained such a diversity of gender/sexual expression for over a decade marks a precious achievement.

Further north in the district of Coochbehar, Moitrisanjog, a collective of mostly Dalit and working class trans and queer persons, has been operating a shelter in the village of Ghughumari since 2011. Sumi Das, the secretary of Moitrisanjog, explains: “In North Bengal, there have never been drop-in centers or shelters beyond bigger towns like Siliguri… Our main aim was to cater to those of us who live in peri-urban or rural areas… When growing up, people like me have few friends… openly visible community members are few… so we suffer from identity crisis due to lack of community exposure… hence we decided to create this shelter… (where) kothi, transgender, and gay people come and express themselves as they please.” Iswar Chanda, who desires to stay in feminine attire but cannot do so at home, says: “This place helps me a lot… I can spend time with people with whom I share my mindset, and talk freely with my kothi community friends… the happiness I get here, I cannot get at home.”

Plural purposes

For some people, these spaces have been a lifeline in crisis situations. As Sumi says, “any community member who faces a problem can get food and shelter here for 10 days… if the problem can’t be solved, they may stay longer or we look for alternatives.” Binod Mahato, a dancer forced to leave home, says: “I face a lot of problems at home, regarding why I am like this, why I dress up… I am kothi and I want to show that I am kothi… But my family is trying to get me married off… so I have come to Moitrisanjog and am staying here.” In one case, a trans woman rejected by her family stayed at the shelter for a year. The Ranaghat space, too, sheltered a trans woman for two months in 2018. These spaces operate in a context where the government has failed to accommodate homeless trans persons in state-run shelters despite the Supreme Court’s directives to set up necessary facilities for transgender people – they are not therefore an ideal solution, but rather a vital stopgap provision that communities are compelled to provide in the context of a neoliberal regime that has cut public expenditure on developmental initiatives while promising social welfare.

These shelters also host regular cultural programmes that provide performance spaces to LGBT artists, and simultaneously help to strengthen regional networks of trans-kothi-hijra people outside metropolitan cities. At Ranaghat, common Bengali cultural events such as Rabindra Jayanti (the birth anniversary of Rabindranath Tagore) and the Bengali New Year become occasions where trans/queer performers showcase their talents. Staples of Bengali middle class culture like Tagore songs, performed by working class kothis and hijras, mix with Hindi and Bhojpuri dance routines performed by community members who work as professional ‘launda’ dancers in Bihar and Uttar Pradesh. Attendees come from all over the districts of Nadia and North 24 Parganas and even Kolkata. The Coochbehar shelter, meanwhile, serves as a venue for rehearsals and performances of regional theatrical forms like Shiv-Parvati plays, shong and bisahari pala, where people seen as male have limited social sanction to enact female roles in mythological or folk stories. As Iswar says, “If I have programs like Shiv-Parvati plays, I can wear my costume from here and go… as I’m not allowed to do so from home.” As I observed while attending cultural programmes at both districts, they also serve as occasions where trans-kothi-hijra people from neighbouring districts can meet and get acquainted, share good and bad experiences, and get counsel from their peers, thus building hubs of networking and support outside big cities.

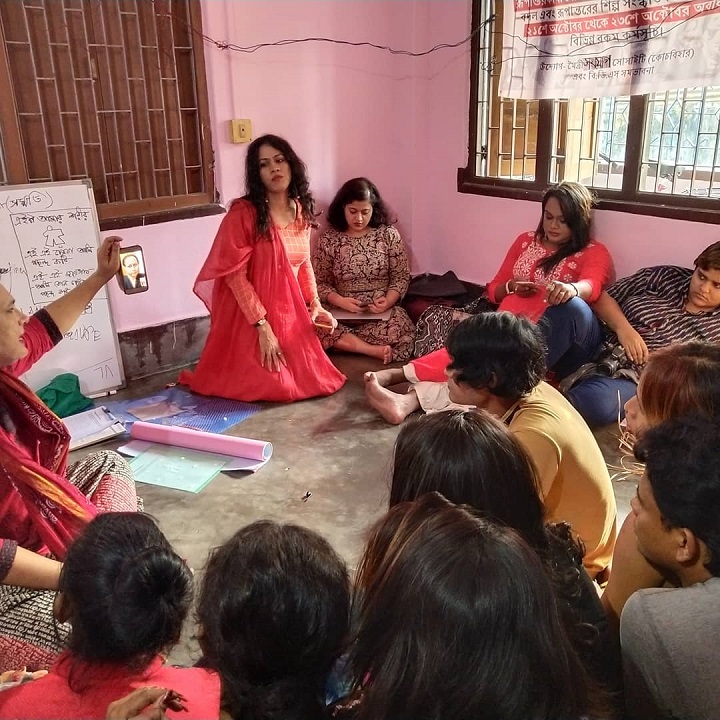

Further, there are events intended to foster sociopolitical awareness and legal empowerment within these communities. In 2019, for example, the Coochbehar space hosted a workshop on building teamwork within the community, a workshop on mental health, and a legal awareness workshop on section 377 (the anti-sodomy statute of the Indian Penal Code that was read down in 2018 to exclude consensual same-sex behavior). The Ranaghat space has also hosted several workshops and discussions on laws such as the Transgender Persons (Protection of Rights) Act, which has been widely panned for curtailing the self-determination of gender identity and treating trans people as inferior citizens.

Such activities have increasingly become intersectional, connecting state and legal discrimination against LGBT people with rising forms of state-sponsored communalism and fundamentalism. Ranaghat, a parliamentary constituency reserved for ‘scheduled caste’ candidates, has lately become a hotbed of electoral mobilization by the BJP, which gained a section of Dalit votes and won the constituency in 2019. In that context, attendees in the aforementioned programs have increasingly raised issues of fundamentalism, communal polarization, and the government’s attempts to restrict citizenship on religious and ethnic lines through mechanisms or laws like the NRC (National Register of Citizens) and CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act). In June 2019, for example, a celebration of Nazrul Jayanti at Ranaghat – the birth anniversary of the poet Nazrul Islam – became an occasion to host a panel discussion on the divisive politics of the NRC, while an attendee initiated an impromptu conversation on the CAA during a year-end celebration in December 2019. While some community members expressed faith in the government during these discussions, several pointed out the adverse consequences of the aforementioned governmental mechanisms for Dalit, Muslim and working class people, especially trans/queer people from these backgrounds, who often lack the official identity documents required to prove citizenship. In a context where some sections of trans and hijra communities have openly professed right-wing positions, these events create a dialogic space that helps to counteract the attempted saffron capture of subaltern groups.

Mixed histories and funding models

Even as they respond to contemporary developments, these spaces continue a longer history. At Nadia in the 1990s, the community gathered at the khols (homes) of community elders and in public spaces like railway platforms used as theks or gathering spaces. One such space at Ranaghat was the khol of Shyamoli Ma (mother Shyamoli), a leader of local kothi-hijra communities who lived independently from her family, making her living as a dancer and later through hijra professions. Her untimely death in 2007 left the community bereft. This was a time of expanding HIV-prevention projects for ‘males who have sex with males,’ funded by international financial institutions like the World Bank through the Indian government. Swikriti Society – a community-led NGO from Kolkata – received one such project for Nadia in 2009, and opened the ‘drop-in center’ (DIC) at Ranaghat where some of Shyamoli Ma’s chelas or disciples began to congregate and work as project staff. At Coochbehar, supportive spaces like Shyamoli Ma’s khol were rarer, and Sumi, facing family violence, left home to work in an NGO at Siliguri. In 2011, she returned and rented a small room at Ghughumari which became an early version of the shelter. Soon they received an HIV project too, and Sumi’s home became a ‘DIC’.

However, governmental HIV funding began to decline in the 2010s and projects at both districts were abruptly defunded in 2012, leaving community members unemployed and temporarily closing the DICs. Struggling to find alternative funds, the spaces and collectives evolved in creative ways. I participated in a meeting in 2013 where the Nadia community discussed how they might build their own organization, less dependent on Kolkata-based activists and HIV funding. Sampriti was established, and reopened the space within a few months using community contributions. However, given the economic position of community members, it was soon apparent that some external funding was needed to cover basic necessities like rent in the long term. Moitrisanjog faced a similar problem, and thus both collectives had to balance autonomy and community-centeredness with the need for funding. They were eventually able to secure small renewable yearly grants from foreign donors. While funded NGOs are often viewed with suspicion in radical leftist spaces, these communities can afford neither a politics of purity around funding nor an uncritical reliance on donors; rather, they follow a mixed funding model combining external grants with smaller community donations.

Erased labours and precarious futures

While the people who sustain these spaces perform significant caring labour by nurturing queer communities and movements in areas beyond the reach of metropolitan organizations, they tend to receive much less credit or media visibility than relatively elite trans/queer activists. On the rare occasions when trans/queer people from marginalized non-metropolitan backgrounds are represented in mainstream media, they tend to be highlighted as exceptional individuals – the “first” transgender university student, “first” transgender judge, etc. Apart from erasing precursors who might have missed the media limelight, this individualist and exceptionalist narrative also erases the role of spaces and collectives that nurture such people. Silk, the aforementioned trans activist from Nadia, has lamented to me that Sampriti helped a particular community member to counter discrimination at her educational institution and finish her degree, but the media predictably highlighted her as an exceptional achiever, and most reports left out any mention of the collective though the concerned individual highlighted its role to journalists.

The labour that sustains these spaces may be understood as a form of queer worldmaking – the creation of “worlds” where non-metropolitan queer-trans-kothi-hijra people may flourish and build new possibilities for sociopolitical transformation; “worlds” that challenge the norms and exclusions of both mainstream society and elite queer communities. However, these “worlds” face a precarious and uncertain future. At Kanchrapara, workers from competing political parties have been eyeing the club as rivalry heats up before the 2021 assembly elections. Meanwhile, recently at Coochbehar in January 2020, some neighbors demanded the closure of the shelter after repeated nighttime attacks by local young men seeking to sexually assault kothis living there. These spaces have survived these crises for now, but their sustenance into the future requires more visibility and support. This piece hopes to be a small step in that direction.

——

[1] As per convention, I use ‘transgender’ and ‘queer’ as umbrella terms encompassing a wide range of gender/sexual identities and expressions: ‘transgender’ refers to gender non-conforming identities while ‘queer’ may be used for both gender and sexual non-conformity.

[2] Names are used with consent; while most are actual, some have been changed for confidentiality.

(All photos used with permission).

The author is a researcher and community member. They are grateful to Arina Parmir for inputs on a draft of the article.

nice put together. sub/peri-urban queer spaces can never be complete without so many countless nameless friends who sheltered and cared for young queers even in the face of brutal societal repression… thanks for writing this.