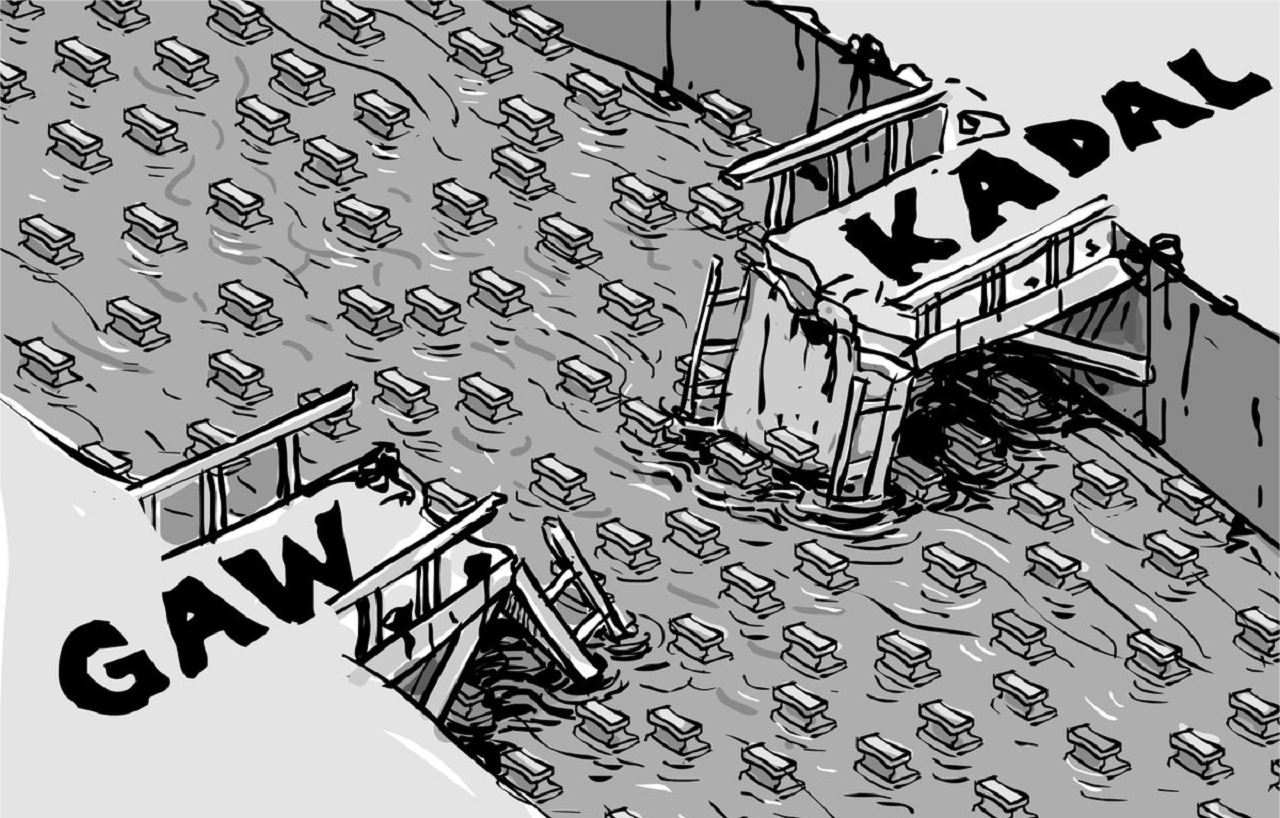

January 21, 2020 marks the thirtieth anniversary of the GawKadal Massacre in Srinagar, Kashmir, when more than 50 persons were killed, and about 200 were injured, as the CRPF opened fire on a group of peaceful protestors. Some, eye-witness accounts say, people jumped into the river Jhelum to save themselves from the firing. It was not until 2012 that the State Human Rights Commission ordered a probe into the incident. Groundxero revisits the tragic incident.

In December 2019, the newly released calendar of holidays for the year 2020, for the newly formed union territories of Jammu and Kashmir, included two significant omitted days. One is July 13, which has been historically observed in Jammu and Kashmir as Martyrs’ Day, in remembrance of the time when protestors against the autocratic rule was openly fired upon, marking what many consider the official beginning of the long struggle for freedom in Kashmir. The other day happens to be December 5, the birthday of the former Prime Minister of Jammu and Kashmir, Sheikh Abdullah, who is also known as “Sher-e-Kashmir” (Lion of Kashmir). Instead, the current regime has instituted a new holiday – October 26th – the day on which Kashmir was acceded to India. In Kashmir, October 26 is often regarded as a “Black Day.”

As is obvious from the above instance, time is politically constructed. A calendar, needless to say, is a historical, political and social construction. Has always been. The fact that January 1 is celebrated as the “New Year” all over the world, is a political phenomenon, the history of which can be traced to many things, not the least of which is constituted by the traditions of Euro-centrism and the planet-wide colonial regimes that often accompany such. States construct calendars. And, in doing so, shape and re-shape public memory. Consequently, the abolition of July 13 and December 5 as crucial holidays in Kashmir, needs to be seen as political efforts of the Indian state to re-shape Kashmiri political memory. In fact, it is an assault on Kashmiri popular political memory. An assault that needs to be seen in conjunction with the abrogation of the Article(s) 370 and 35A. If the abrogation of the Article (s) 370 and 35A offer the material and legal basis through which the intensely-disputed accession of the region of Jammu and Kashmir within the Indian national territory is further deprived of the limited autonomy it has been given, the abolition of the holidays in the region provide the cultural basis for the curbing of such autonomy. Needless to say, the calendar ceases to be a neutral entity within the political landscape of Kashmir. The Indian state makes it into a site of political domination and re-structuration.

In fact, the form of the calendar has been used by Kashmiri activists and artists as an important political form in creating a narrative of Kashmiri dissent. Beginning in 2016, Association of the Parents of the Disappeared Persons (APDP), an organization that has played a momentous role in the human rights movement in Kashmir, has produced a calendar of the disappeared. Here, every month has been identified by a “disappeared” and his story. A rough sketch follows the narrative. The calendar, then, itself becomes a testament to the ever-present spectre of state violence in Kashmir. Every day of the month – for all 30 days – the viewer is almost made to stare at a face who does not exist in the world anymore. No one knows whether he will come back. If he will ever come back. No one even knows what happened to him.

It is almost like staring at someone who is forever stuck in the space between “life” and “death.” A limbo. And with him, are his viewers. Within a field of vision that is constituted by an uncomfortable mourning, an uneasy form of memorialization.

Yet, a complicated form of memorialization it is. Complicated, because these are the faces and lives that the Indian state has chosen to forget. States routinely reduce both lives and deaths to numbers. And, being reduced to numbers, connotes a kind of violence. But, even numbers, acknowledge a kind of existence. In Kashmir, the Indian state often exists in denial of the numbers. The numbers of human beings it obliterates, are washed out of even of the symbolic and abstract existence of the numbers, in the state’s sheer refusal to acknowledge and be accountable. The calendar, then, becomes a naming of that practice of systematic obliteration exercised by the Indian state in Kashmir. The calendar, then, also becomes a cultural, political and social form, that initiates a form of measuring time through forced disappearances. And, the spectre that such forced disappearances inevitably bring with them, is that of death. Time – especially Kashmiri time – comes to be measured through death. Or, the ever-present possibility of death.

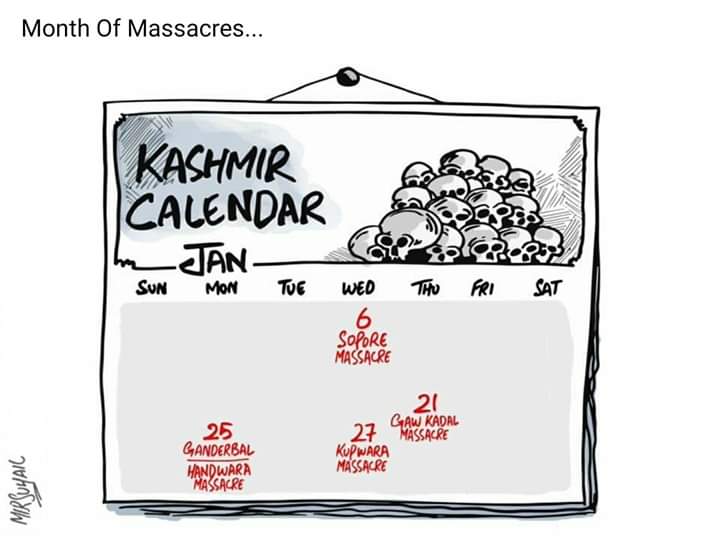

The month of January, in Kashmir’s history, has a complicated association with death. In fact, when seen from the vantage point of a Kashmiri sense of time, January can well be described as a “Month of Massacres”, marked as it is by four such events. And, this is how the month is often remembered and represented by Kashmiri artists. In a recent painting, entitled “Month of Massacres”, Kashmiri artist, Mir SuhailQadri, again takes up the form of the calendar. Done overwhelmingly in black and white, with a visual of skulls adorning the month of January on the right-hand top, only four days on the calendar have been marked – 6, 21, 25 and 27th. Painted in red, each of these dates signifies a massacre – Sopore, GawKadal, Ganderbal-Handwars and Kupwara. The rest of the calendar remains ominously empty, marked by a white that overwhelms. On the top left hand side, are two words written in bold and black letters – “Kashmiri Calendar.” And, not just a mere calendar. The insertion of the word “Kashmiri” embodies a need to characterize time in Kashmir as something specific and different. And, that difference is constituted by death. So much so, the other twenty-seven days in January – which are not marked by massacres – almost cease to matter. Death is a form of emptiness. A profound conclusion. But, such is the intensity of the spectre of death in Kashmiri social life, that its absence makes time itself empty.

Shah Abbas writes in his essay in Kashmir Life, “During the intervening night of January 20 and 21, CRPF troops conducted widespread and “warrantless” house-to-house searches in Chotta Bazar, a congested locality in downtown Srinagar. Authorities claimed that the presence of several armed militants prompted the search operation. However, none of over 400 persons, who were dragged out of their homes into the biting cold of the night and arrested turned out to be a militant, neither was any weapon seized. It was during this search operation that allegations of molestations of women were made, something which had never happened before in the history of Kashmir conflict. And with this, the peace of Kashmir was shattered.” While there are many accounts of the events of the event, what everyone agree upon is that, on the night of January 20th, 1990, it became known that several women in Chotta Bazar area of the downtown Srinagar had been molested during a crackdown. The very term “crackdown” has a curious social and political life in Kashmir. Possibly one of the most common words in English in Kashmir, the word invokes simultaneous dread, unspoken rage and deep humiliation. The everyday emotions of a militarized occupations. Crackdowns, in Kashmir’s history, are also deeply associated with instances of militarized sexual violence. As was the case in Chotta Bazar in January 1990. When the news reached the neighbouring areas, a spontaneous crowd had gathered, which soon, began to swell in numbers. A peaceful protest had begun, which began to walk towards the downtown area, crossing the GawKadal Bridge (The word “kadal” means “bridge” in Kashmiri). When the rally had almost reached the bridge, the security posted in there at the behest of the-then governor, Jagmohan, had open fired. According to the official reports, 53 were killed, while over 200 were injured. It took the State Human Rights Commission twenty-two years to order a probe into the incident. Not only so, DSP AllaBaksh, who was held to be responsible for the event in many accounts, was not only let scot free, but was also given promotions and rewards within the department.

By the time the GawKadal Massacre happened, the concept of a similar event was not at all unheard of in Kashmir. In 1947, for example, there were massacres of Muslims in Jammu, the correct numbers of the death in which still remain debated, and largely unknown. But, the GawKadal Massacre remains a significant event in Kashmir’s history of state-sponsored massacres. Many commentators suggest, for many who came of age in the 90s, the massacre suggested the impossibility of developing a democratic Kashmiri movement on the demands of self-determination. Abbas comments, “ TheGawkadal massacre proved to be a turning point in Kashmir’s history. Soon, the raging struggle of a few angry Kashmiris morphed into a popular uprising. Thousands of young men, braving snowclad mountains and bullets of Indian soldiers, crossed the Line of Control (LoC) into Pakistan-administered Kashmir to get arms training.”

Because, a massacre is a form of communication, after all. A drastically unequal communication. But, a form of communication nonetheless. A form of communication where one side is told, their lives do not matter. Let alone their voice. In fact, to try to have access to one’s voice, in a society ruled by the spectre of massacres, is to be dead.

A massacre, therefore, leaves behind a dubious legacy. A history of being silenced, but also a history of attempting to speak. As in the case of the GawKadal Massacre. In Kashmiri political discussions and social life, the event would mostly be talked about as a reference point. A beginning of sorts of a new kind of tehreek (the movement). Otherwise, what is there to talk about when one talks about a massacre? Especially one that was committed during an instance of collective raising of voice? The overwhelming fear of the impending death? As does the of the lone survivor GawKadal Massacre. Or, does one ruminate on that feeling of invigoration that comes with walking in unison with others? The one that precedes death? The truth is, a massacre is a silencing on a mass-scale. The concrete realities of a massacre can hardly be narrated. Because, for the massacred, there is no aftermath. And, for those who are left behind, and those who survive, the material details of a massacre are often too traumatic to be remembered. The massacre, then, often becomes a date, suspended forever in that space between forgetting, remembrance and semi-remembrance. As it is, the GawKadal Massacre would unleash a new political reality in Kashmir. One that comes with a normalization of massacres in Kashmiri social life. An occurrence that would punctuate too many of the peaceful demonstrations in Kashmir. For others, the possibilities of one will always loom in the background.

January 21, then, comes in Kashmir with a heavy burden. A burden of memory, of course. But, also a question. What can the memory of a massacre do in the context of a 72 year long military occupation? Does it only reinforce despair? Does it enable a mobilization of narratives that creates a very different notion of Kashmiri time than the one created by the Indian state? And, therefore, a different sort of politics? The truth is, it is possible to be an Indian mainlander, and live in blissful ignorance about Kashmir, in blissful ignorance about the Kashmiri calendar and the ways in which it is dotted with death. And the Indian state makes every effort to make sure that the state of such ignorance continues. This is precisely the place where artists like Mir SuhailQadri intervene. In their re-imagination of the Kashmiri calendar, they make visible what the Indian state would like to erase. Has so far erased. In doing so, the very form of an alternative calendar is elevated to a form of resistance art in Kashmir.

Cover Artwork courtesy: Suhail Naqshbandi (https://twitter.com/hailsuhail). The image of “Month of Massacre” is by Mir Suhail Qadri taken from his facebook page. The image of APDP calendar is from the organization’s web page (www.apdpkashmir.com).