Encounter killing of accused in Telangana is hardly a deterrent against rape. On the contrary, it magnifies the patriarchal notions of men protecting the honor of women through violence, which fuels myriad violence against women everyday. Writes Rumela Sen.

“Two Wrongs don’t make a Right, but they make a good Excuse”

-Thomas Szasz

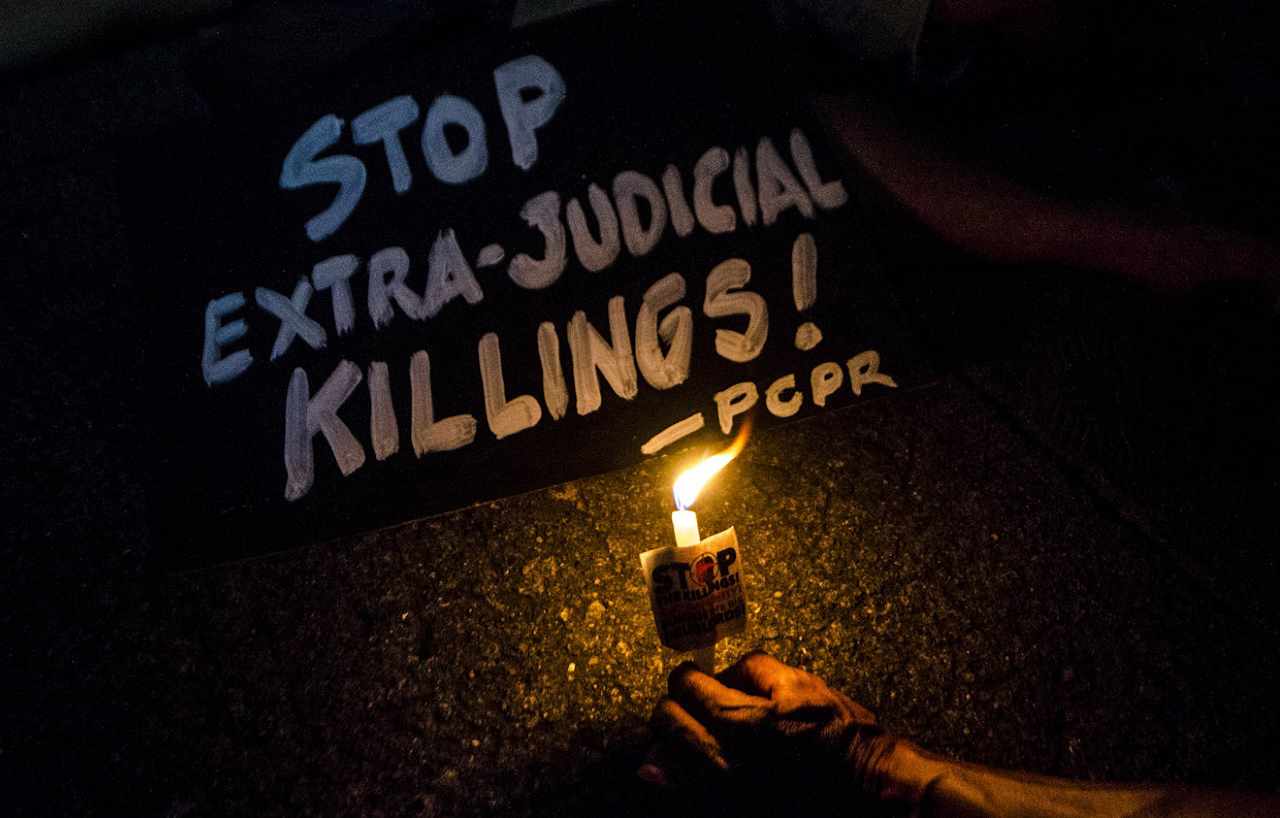

There is an element of serendipity in the word ‘encounter’. It alludes to a chance rendezvous, an unexpected meeting. Ironically, extrajudicial killings by the police are called ‘encounter’ in South Asia, even though such “encounters” do not occur by chance. They are meticulously planned to avoid culpability of custodial death and are blessed by the political masters. It is all but predictable that in such encounters only the policemen get to pull the trigger, and the suspects already under arrest end up dead and no one is even held accountable for these murders.

In most cases, ordinary people take the news of encounter deaths as another fait accompli presented to them by the high and mighty. Unlike the price of onions, encounter killings of suspected militants in Kashmir or Punjab did not affect our routine lives. But when the police encountered the rapists of Dr Reddy in Telangana, the news was met with jubilation in many quarters that justice was served instantaneously and the victims got what they deserved.

The police dutifully claim that those men had to be gunned down because they had tried to escape or attack the police. The victim’s perspective is, of course, unavailable. But if that rejoinder about the suspects unruly behaviour were absent, would the police be held accountable for breaking the law it is appointed to uphold? Isn’t it common knowledge that most encounters are ‘fake’ anyway?

According to the National Human Rights Commission, between 2002-2013, there have been roughly 995 cases of encounter killings in India, many of which are fake. In other words, few, if any, buy the story that unruly conduct by the victims made them susceptible to extrajudicial death sentence. When certain alleged outlaws are ‘chosen’ for encounters, the police and politicians have decided their fates anyway. If those men did not try to run or attack the police, would they have averted their deaths?

It seems that such spectacles of state-sponsored violence thrives on popular approval. It is somewhat equivalent to the ancient Roman practice of “damnatio ad bestias”, where convicted criminals were exposed to wild predatory animals, often in an amphitheater, where the public cheered the bestial killings. Death is gloomy and melancholic unless those dying are convicted of heinous crimes like rape. Then people cheer and celebrate their spectacular death in the name of protecting the ‘honor’ of our women. In a way, the latest encounter in Telangana is much like an honor killing – some found it satisfying, while others expected harsher punishments like castration, amputation etc.

Justice delayed is justice denied, they say. It is one of the most common justifications for extrajudicial death sentences. When the police and politicians mete out speedy justice by killing suspects, they earn not only public approval but also career rewards. Those implicated in these cold-blooded murders are handsomely rewarded with promotions and gallantry awards, cash and fame. Their political masters use it to showcase their “tough on crime” stance.

The film industry in India has also generously glamorized and valorized ‘encounter specialists’ as intrepid heroes who risk their lives and sidestep the legal protocols to mete out real justice. Well-known encounter specialists, known by the number of ‘hits’ they have scored, have inspired hit movies. For example, Daya Nayak of Mumbai Police, known for gunning down 83 men, all of them suspected gangsters of Mumbai underworld, inspired an action thriller titled Ab Tak Chhappan (Fifty Six So Far). Thus the prevailing norms of accepting, validating and even valuing extrajudicial killings as acts of bravery by true patriots effectively mute dry arguments about how they jeopardize norms of democracy, accountability, justice and due process. It has been reported that Ravindra Ange, an infamous encounter specialist of Maharashtra Police, threw a party to celebrate half-century score, after killing 54 alleged criminals. Other well-known encounter specialists include Rajbir Singh (51 kills), Sachin H Waze (63 kills), Vijay Salaskar (83 Kills), and Pradeep Sharma (104 kills). Such personalities have achieved name, fame, cash and Wikipedia entries for their exploits.

Under such circumstances, why would a rational, competent police officer not aspire to become an encounter specialist? What are the potential discouragements? Take the case of Daya Nayak again. He was temporarily suspended and investigated by the Anti-Corruption Bureau, was eventually acquitted and returned to Mumbai police, with a movie made about him and the media applauding him as the hero doing his job and keeping us safe.

Put in that context, it is perhaps not entirely surprising that Mr. V.C. Sajjanar, the senior IPS officer and police commissioner of Cyberabad who oversaw the recent encounter of the four men accused of a brutal rape in Telangana was already ‘famous’ for his links to another encounter a decade ago. As a young superintendent of police of Warangal district in 2008, Sajjanar rose to fame after his team gunned down all three accused in the Kakatiya University acid attack case in 2008. Hours after the arrest of suspected attackers, they were taken to the scene of the crime as part of an evidence gathering exercise when they allegedly attacked the policemen before the police shot them dead in self-defense. On December 6, 2019, four men accused in the gang-rape and murder of Priyanka Reddy were shot dead by the police and the modus operandi is remarkably similar. This brings us back to the predictable, unsurprising aspect of encounters: eleven years later, we have the same police officer at the helm, similar chain of events leading to the death of suspects of similar crime amidst similar public approval.

Telangana is no stranger to brutal policing. In the wake of this latest incident, it is impossible to ignore that a part of the police here were trained to become “greyhounds”, deliberately named to invoke the image of wild beasts who hunt down and kill their prey relentlessly. Grey Hounds has the mandate to hunt down Naxalites across state borders without being restrained by jurisdictional limits or norms of accountability. The history of encounter killings in India goes back to the colonial era, but in Telengana and Andhra Pradesh, it became the most preferred tool of maintaining law and order in the wake of the Naxal uprising since the late 1960s.

The Andhra Pradesh Civil Liberties Committee (APCLC) has for many years tracked encounter killings and filed complaints with the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC). In March 1993, for example, about 285 encounter killings, were documented by APCLC. The NHRC investigated five of them and found the complaint justifiable. On that basis, it made specific recommendations to the State government to ensure that every custodial death must be registered through an FIR and investigated. When the police are involved in a cognizable offense, the case must be referred to the Criminal Investigation Department and properly pursued.

The Andhra Pradesh government accepted the recommendations and accordingly amended its Police Manual in 1996. In 1997, the APCLC again documented 197 encounter deaths, and not a single FIR was registered. Between 1997 and 2003, 1,314 more people were killed in encounters in Andhra Pradesh. The APCLC filed 30 petitions before the Andhra Pradesh High Court, and not a single FIR was registered. Between 2003 and 2007, there were 524 encounter deaths, followed by twenty petitions and no FIRs. Telangana has also witnessed many judicial inquiries against the lawless behavior of the police. Across the districts of Karimnagar, Warangal, Adilabad, and Nizamabad, rights activists have tried to hold the police accountable for numerous instances of false criminal cases, custodial deaths, and indiscriminate firings.

Unfortunately, there is no happy note to end this discussion with. There are surveys that show that Indians do not trust their elected leaders, police, and courts of law. But supporting “encounter killings” as a bulwark against the weak and slow legal process is dangerous – it further obfuscates the thin line that separates the mafia, drug cartels and such who break the law from the police who are expected to enforce it. To emphasize the dividing line between the two, we need the police be more accountable to the law when others aren’t. The society that allows that line to blur risks going down the slippery slope of anarchy.

Article 21 of the Constitution of India states that “No person shall be deprived of his life or personal liberty except according to procedures established by law”. In the case of Om Prakash v State of Jharkhand, the honorable Supreme Court of India has observed that staged encounter killings by the police amount to “state-sponsored terrorism”. Globally, under the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR), adopted by the UN General Assembly in 1966, extrajudicial killings are forbidden and termed as criminal activities.

The recent extrajudicial killing by Telangana police should have sent shivers down the spines of India’s constitutional democracy. Instead, a huge crowd reportedly gathered on a bridge overlooking the murder spot and cheered the police, with some even showering flowers on them. Some feminists and activists also welcomed the instant gratification of deaths for a death . However, there is no evidence that extrajudicial killings are effective deterrents against crime. In Rio de Janeiro, for instance, the crime index is ~80, one of the highest in the world.1 In 2018 alone, there were over 1500 reported killings by the Rio police, many of them allegedly fake encounters. The story repeats itself in almost every high crime city, proving that the trigger-happiness of police officers do very little to bring down crime. What truly works against criminal behavior is well-known and well understood. But long-term changes in socio-economic structure and patriarchal values are not as politically expedient. In addition, for a deterrent to work, it should be the assured outcome every time a rape occurs. When the rapists of Unnao or Kunan Posphora are never held accountable at all, one encounter killing in Telangana is hardly a deterrent against rape. On the contrary, it magnifies the patriarchal notions of men protecting the honor of women through violence, which fuels myriad violence against women everyday.

Note:

- (From this source: “Crime Index is an estimation of overall level of crime in a given city or a country. We consider crime levels lower than 20 as very low, crime levels between 20 and 40 as being low, crime levels between 40 and 60 as being moderate, crime levels between 60 and 80 as being high and finally crime levels higher than 80 as being very high.”)

The author Rumela Sen is a political scientist at Columbia University, NY