In the second part of his two-part essay, Zeeshan Husain looks at the position of women in India from AD 600-1750, focusing on historian Irfan Habib’s “Medieval India: The Study of a Civilisation” (2007), and AS Altekar’s, “The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization”. Habib divides this period into three parts — early medieval India (AD 600–1200), India under the Sultanates (AD 1200–1500), and Mughal India (AD 1500–1750) — and uses the themes of economy, polity, society, science, technology, religion, literature, and art to study the three periods separately. It is important to note that caste and gender hierarchies were already quite pronounced in pre-colonial India. In this essay, the author takes up the task of trying to understand the complex ways in which gender relations were actually organised over this time, in a society defined through caste. The first part in the series, on “Understanding the History of Caste in India through Irfan Habib‘s Work” can be read here.

Women in Early Medieval India

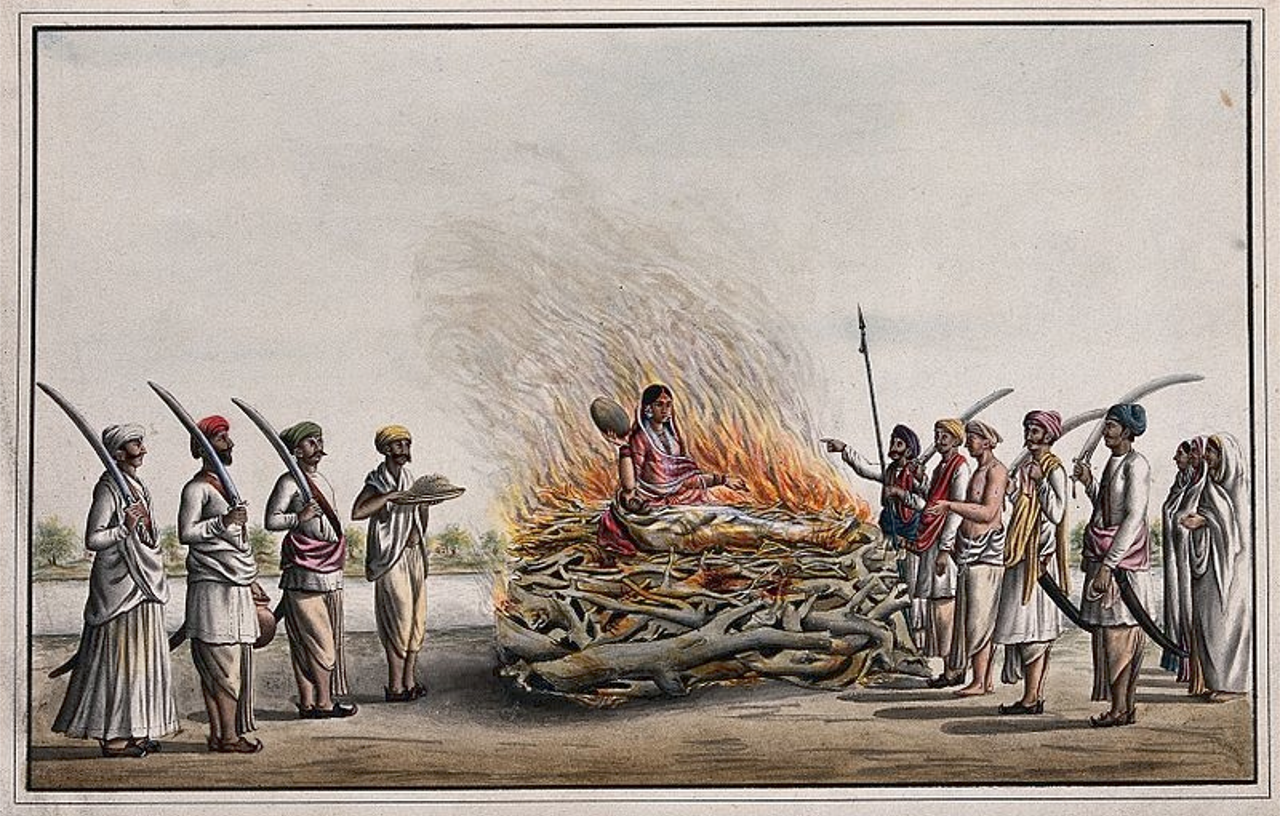

Caste and the position of women in society are interrelated. To reproduce ‘caste’ one has to sexually subjugate the bodies of its women through endogamy and other social techniques. Consequently, when we find evidence suggesting a growing rigidity of caste system from early medieval times, we also find indications of a gradual lowering of women’s position in society. This point is well taken by BR Ambedkar when he says in his essay Castes in India (1916), “endogamy is the only characteristic that is peculiar to caste”. The practice of widow burning or sati became fairly common all over India by the eleventh century among the widows of rulers, nobles and warriors. Some evidence like the Lekhapaddhati — a collection of documents from Gujarat — also show that women could be bought and sold as slaves, and were made to do all kinds of work, including the dirtiest and toughest kinds. They were also subject to physical and sexual violence. On the other hand, women employed as professional dancers in royal courts and the deva-dasi or temple courtesans appear to have been another large class of women.

Habib cites AS Altekar’s work, The Position of Women in Hindu Civilisation as one of the references that he draws upon when discussing the history of women in Medieval India. Altekar focuses on the history of widows in particular, to understand the history of women as a class.

In Medieval India, a period that witnessed the spread of Hinduism and the caste system, one of the customs that historians like Habib and Altekar have looked at is that of Sati. “From about 700 AD, fiery advocates began to come forward to extol the custom of Sati in increasing numbers,” writes Altekar. As an example, he cites the Parasarasmriti, a post-Manu code of laws that lists out the governing principles for the Kaliyuga (the Age of Kali), compiled during this early medieval period. In addition, it contains humiliating dictates against the lower-caste Shudras.

Between 700 and 1100 AD, Sati became a more frequent phenomenon than earlier in northern India. Among Kashmir’s royal families, with the death of royal men even mothers, sisters, and sister-in-laws ascended funeral pyres! Only later, however, would Sati become a prevalent custom among the north Indian royal families at large. Recorded cases of Satis in northern India outside Kashmir were still very few during the period 700 — 1200 AD, compared to the numbers we find from later on. However, by this time, Sati had become a custom well recognised in the canons of Hinduism, “for we find it traveling to the islands of Java, Sumatra and Bali along with Hindu emigrants,” notes Altekar.

It is also interesting to note that the early medieval Brahmanic texts, while glorifying the ideals and custom of Sati, prohibited Brahman women from committing Sati themselves. This ban was later lifted by the Brahmans, perhaps to imitate ‘glorious’ Kshatriyas. This would later impact a large number of Brahman widows who were forced to kill themselves, particularly in states like Bengal and UP.

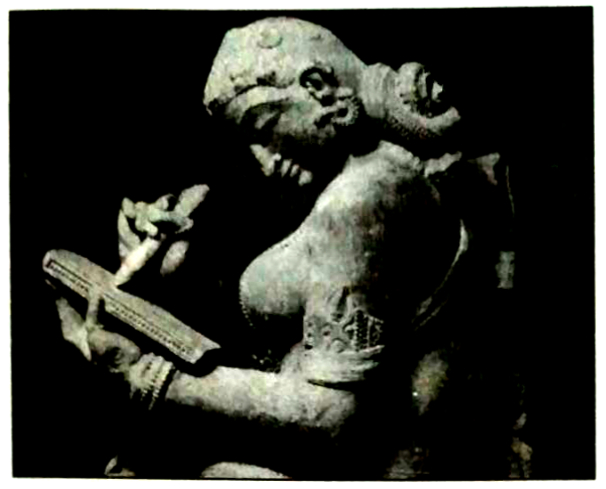

There were also a few accounts that are an exception to these dominant trends of growing Brahmanical patriarchy. Habib recalls celebrated historian of Kashmir Kalhana’s account of Jayamati, “brought up by a dancing woman, and notorious for opportunistically changing her male partners. She ultimately became the Queen of King Uchchala of Kashmir (1101-11) and earned great repute in that position, for her benevolence and wisdom”. Incidentally, Jayamati also had to perform Sati, and as Altekar notes, against her own will. While education in Hindu society was largely limited to men, Habib points out the famous sculpture of a woman writer at Khajuraho (10th-11th Century).

The woman writer from Khajuraho. Source: Medieval India: The Study of a Civilisation (2007), Irfan Habib.

Women in the Sultanate period

In the Sultanate period, just as in the case of the caste system, there was no substantial change in the treatment of women. The condition of Muslim women could be said to be slightly better than their Hindu counterparts since Islam permits daughters to inherit their parents’ wealth and allows widow remarriage. Practices like sati and widow repression remained alien to Muslim custom, much like the case of ‘lower caste’ communities. Habib however also reminds of “the tolerance to polygamy and unrestricted concubinage” — something that Islamic law shared with the Dharmashastras. Slavery existed before, but this increased in the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries as slaves were obtained both in war and in lieu of unpaid taxes. They were made to work within the households and as well as craftsmen. Habib writes, “In the Delhi market early in the fourteenth century a woman slave for domestic work cost no more than a milch buffalo. Sultan Firoz Tughluq was reputed to possess 180,000 slaves, of whom 12,000 worked as artisans. His principal minister, Khan Jahan Maqbul possessed over 2000 women slaves”.

“[Islamic law] also heavily stressed on enforced seclusion and veiling of women and permitted pre-puberty marriages,” he adds. There was, however, nothing in Islam against women writing and reading, and Habib draws our attention to a fifteenth century dictionary Miftahu’l Fuzala (1469) that shows a small girl learning to read along with boys before a school master. It was the Sultanate period when Iltutmish’s daughter Raziyya reigned as a Sultan herself (1236-40), which also caused a scandal.

There are small indicators of the position and role of women in the Sultanate period. We have at Tirupati copper sculptures of Krishna Deva Raya (1509-29), emperor of Vijayanagara, with his two queens. There was also the culture of dance and music. Ziya Barani’s Tarikh-I Firoz-shahi provides glimpses of this in royal courts. Citing Barani, Habib tells us that in thirteenth century young girls were trained in Persian and Hindi music by the courtesans in the Delhi court like that of Jalaluddin Khalji (1290-96).

Women in Mughal India

On to the Mughal times, we have greater clarity about the role of women in society. There is no doubt that society, in general, was oppressive to women, and the growing influence and number of Smritis not only maintained but also elaborated on the restrictions women faced. The nature of oppression, however, varied across classes and communities. And it has evolved along with time.

The common Hindu women had negligible rights of inheritance. Child marriage was prevalent. Bride price was common among lower castes, while dowry among the higher castes. Widow remarriage was possible in many of the peasant and pastoral castes, such as Jats, Ahirs, and Mewatis. Women did various household chores and participated in agricultural activities but not tilling. India was one of the few countries in the world where women carried out heavy tasks in building construction. While claims to inheritance were legally allowed among the lower castes, in practice however such claims were frequently disregarded.

Women of the upper castes in general had greater leisure, but also faced much greater restrictions. Seclusion was strictly imposed, widow remarriage was absolutely prohibited (Habib). The Mughal administration intervened in sati, and tried to discourage it by ensuring that it was a ‘voluntary act’ on a case by case basis. But such interventions remained mostly ineffective. Humayun wanted to ban Sati, in the case of widows who had passed the child bearing age. But he could not take effective steps to that effect. Akbar, in the 22nd year of his reign, appointed inspectors to ensure that “no force was used to compel widows to burn themselves against their will.” “[Acts of Sati] occurred two or three times a week at the capital, Agra, during the late years of Jahangir’s reign,” writes Habib.

In fact Sati, by this time, had become a much more common practice among the north Indian royal families, specifically those in Rajputana. “When Raja Ajitsingh of Marwar died in 1724, 64 women mounted his funeral pyre. When Raja Budhsingh of Bundi was drowned, 84 women became satis,” notes Altekar. The practice had also spread to the warrior classes of the Southern peninsula, though to a much lesser degree than their northern counterparts. While Maratha ruling families by this time claimed Rajput descent and therefore could not remain immune to Sati as a practice, the frequency was still not as high as compared to Rajputana. “When Shivaji died [in 1680], only one of his wives became a Sati. The same was the case with Rajaram. The Queen of Shahu was compelled to burn herself owing to the political machinations of her mother-in-law, Tarabai. There are very few other cases of Satis recorded among the annals of the Maratha ruling families at Satara, Nagpur, Gwalior, Indore and Baroda,” writes Altekar.

Bengal had the highest incidence of Sati during the later Mughal period, in the country. “The percentage of Satis in the Hindu population of Bengal was much larger that what [was] obtained in the presidencies of Bombay and Madras, or even in the division of Benares, which was the greatest stronghold of orthodoxy,” he writes. The annual average of Satis in the Calcutta division between 1815-28 was 370. In comparison, the average for the Dhaka and Murshidabad divisions, both predominantly Muslim, were 44 and 19 respectively during the same period. “Most of the Satis in Bengal and UP were from the Brahmana caste,” Altekar observes. He attributes the prevalence of Sati in Bengal to eliminating the widow’s heirship of property.

Like everywhere in history, here also there are stories of resistance against patriarchy. Ahilyabai Holkar, the Holkar queen of the Maratha Malwa kingdom not only did not commit Sati after her husband died, but ruled from her capital at Indore for 30 years after the death of her son. Sanchi Honamma was a poetess in the court of Chikkadeva Raya of Mysore (reigned 1672-1704). In her Hadibadeya Dharma, written in Kannada language, she protests against women being considered as inferior to men. Matrilineal systems prevailed among certain communities in Kerala, and among several communities in the North East such as the Garos and the Khasis of Meghalaya. The 3rd Sikh Guru, Amaradas, condemned the custom of Sati, “and it was not followed by the Sikhs for a long time,” writes Altekar. Muslim women had a similar, and at the same time different, position. Women could claim a dower for themselves from their husbands as settled in the ‘marriage contract’ and also inherit property, though in proportions less than the male members of the family. While observing marriage contract documents in Surat from the first half of the seventeenth century, Habib finds that “wives obliged the husbands not to marry a second time or maintain any concubine”. The marriage contracts also forbid the husband from domestic violence, and ensured a minimum amount of subsistence for the wife. It is interesting to note that Aurangzeb changed the rules allowing widows to keep the entire land-grants of their husbands for life. While it is probably the case that middle class Muslim women were largely illiterate, we also have a picture of a schoolgirl along with her brother, painted around the late fifteenth century. There was also the exceptional case of Humayun’s sister Gulbadan Begum being educated while her husband was illiterate.

In Conclusion

In medieval times, just like caste arrangements, patriarchy was also deeply entrenched. Strict restrictions were placed on the bodies, movements, and legal and economic rights of women. But we also see here that there were certain recorded exceptions, as well as variations across religion, castes, and regions. The position of women was slightly better among the Muslim and ‘lower caste’ communities, though almost every community was already organised in accordance with the laws of patriarchy. In times such as our own, where ahistorical images rule our consciousness, such renderings of history by historians like Habib assume a vital importance.

References

1. Habib, Medieval India: The Study of a Civilisation

2. AS Altekar, The Position of Women in Hindu Civilization

The author is a research scholar in Sociology, at the Jawaharlal Nehru University.

Discrimination against woman must stop

Dalip Singh Wasan, Advocate.

In spite of all efforts made till date, woman in India is still placed at second rates citizen. When nature has given her equal number on earth, they must be placed at equal place in all sectors. We should ensure them proper health, proper education, proper training, proper employment and must be provided with proper income and she must stand at her own feet and should not be dependent on men. The main cause of her second position is society is because of her dependency on man and because of this dependency, she has become a weaker section of society and because of this weakness she is victim of all evils.

The parents, the state and the society must ensure that woman is not discriminated. The parents must bring her up like a son and must ensure thqt she is provided with proper health, proper education, training and must be raised like son and must be considered like son and should stop this dowry system and instead they must be given her share in assets and properties of her parents. These assets, cash, ornaments and properties may not become part of assets of her husband, but must be owned by her in her own name throughout.

We should ensure that these household affairs must also be shared by the husband and she must be free from household affairs. We can establish Service Societies for supply of prepared food items, laundries, crèches, serving old people, ill and old people and woman too may get time to attend work outside her house. We must ensure that she gets equal share in all jobs and once she is on her own feet, she shall not be victim of present evils like turning a keep, turning a call girl, turning a woman selling her body, turning a victim of rape and adultery. Even she would not become a keep. All these evils had been created in this world only because she had been placed at a second position and she had been placed at a position where she is just dependent upon the man, her husband. Earning is the first item which shall raise the position of woman in the society.

101-C Vikas Colony, Patiala.