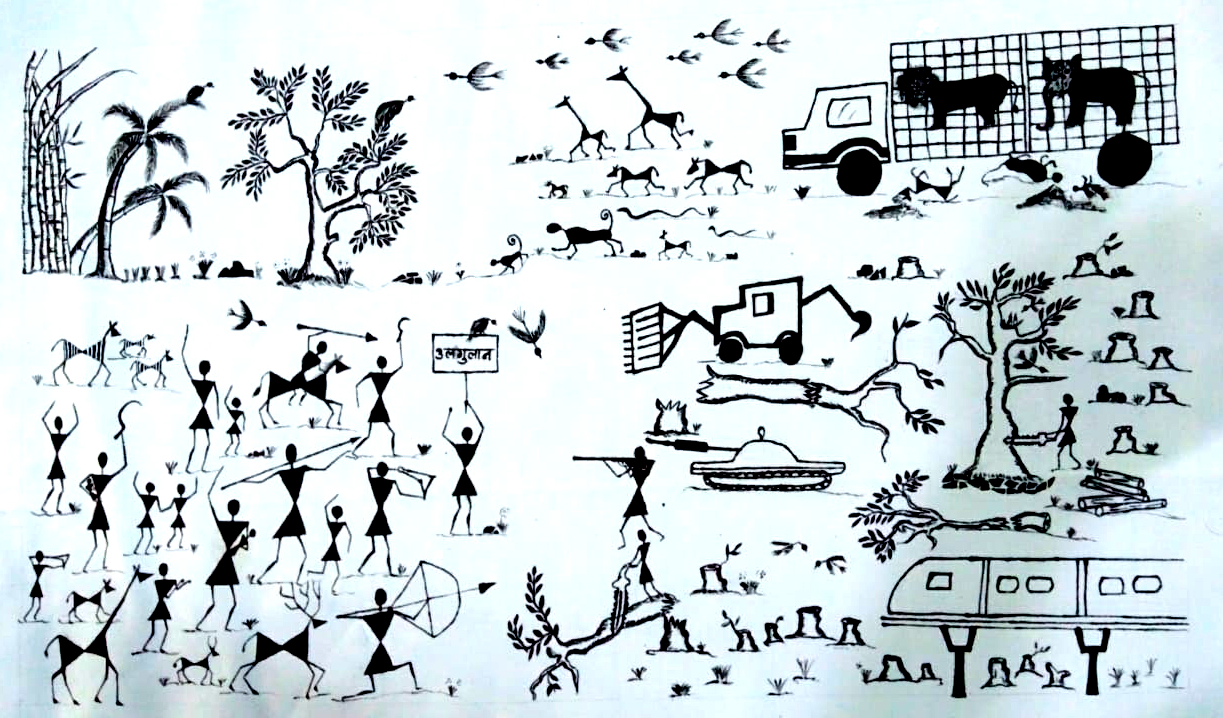

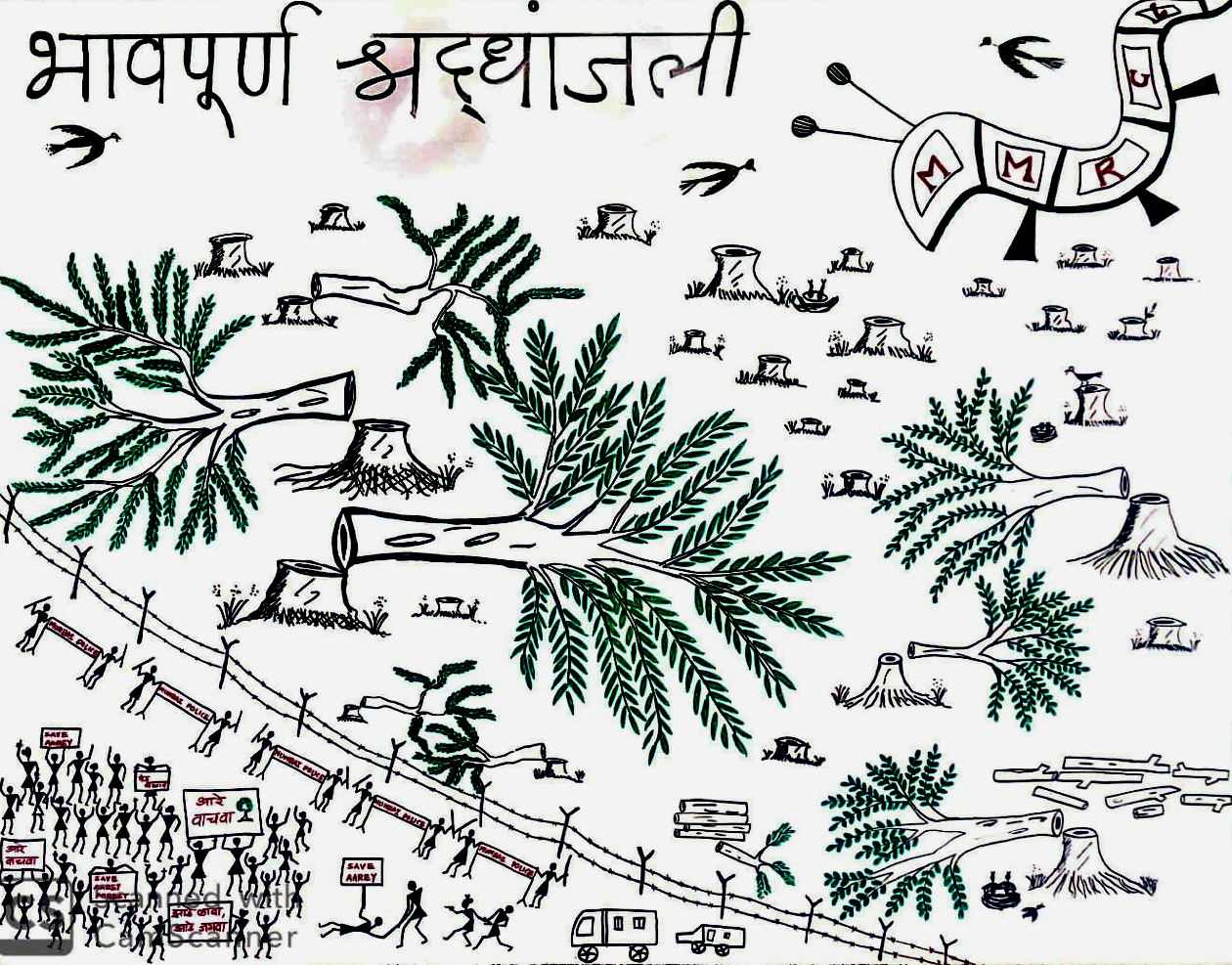

While much has been said and written about the impact of the cutting down of the Aarey forest in Mumbai on climate and the environment, what has remained largely under-reported is the impact this will have on the lives of those who are residents of these forests. Mumbai’s Adivasi settlements are under siege. They are the rightful keepers of the forests and not the Government or the MMRDA. These are the people who have historically fought against incursions into these forests by the financial metropolis. These are the people who are fighting right now for keeping their lands, their gods, and their forests, writes Arati Kade. The Warli paintings used in the report are by Akash Bhoir from Keltipada Adivasi Gaothaan, Aarey.

Mumbai’s Adivasi settlements

Based on surveys conducted by the Tribal Research and Training Institute in Pune, there are a total of 222 Adivasi padas (hamlets) in Mumbai. Out of these, 27 are in the Aarey forest. The total Adivasi population of Mumbai is more than 1 lakh, out of which around 10 thousand people live in the Aarey forest areas.

Mumbai’s Adivasi padas’ fight to protect their lands and forests is not new. The Aarey Milk Colony took land from these Adivasi families in 1949 in order to build a dairy for the city. In the following decades, however, this land was distributed repeatedly among various other agencies, for multiple other purposes. The initial area of 3,162 acres of forest land has steadily dwindled over the decades. In the 1970s, more than 100 acres were given to the State Reserve Police Force. Another chunk of land was given to the Bombay Veterinary College. Around 300 acres of land was given to the Film City, and 145 acres of land was given to the Konkan Agricultural University.

In 2009, another 100 acres were given to the Force One commando force of the Mumbai Police for them to build their headquarters, firing range, etc. Here, however, three Adivasi padas resisted eviction and refused to move. In June this year, 40 hectares of the Aarey forest were cleared to extend the Byculla Zoo, without enclosures. This was done to allow the zoo to offer night safaris to tourists. The 82 acres of land committed to the Metro project is thus the latest in the long history of regular land grab of the Aarey forest lands.

Last week, the Government chopped off thousands of trees by force in the middle of the night, to clear up land for the proposed Metro carshed. This was done after a Court order gave them the go-ahead. The adivasi padas were placed under barricades to ensure no one could come in the way of the carnage. The role of mainstream political powers in this episode has, not surprisingly, been that of blatant betrayal. “During the 2014 assembly election campaigns, the Shiv Sena promised that they would protect the adivasis and the forest at Aarey. But now the Nagar Sevak, the local MLA and MP – all of who are from Shiv Sena – are contributing in destroying the forest,” said one of the residents of the Naushyacha pada. While the trees were being cut, instead of passing orders to stop it, Shiv Sena leaders such as Aditya Thackerey, President of the ‘Yuva Sena’, the Shiv Sena youth wing, was found tweeting lip service against the cutting of trees.

Yuva Sena leader Aditya Thackerey in a ‘Save Aarey’ rally, prior to 2014 General Elections. Current Nagar Sevak, MLA and MP from the area all belong to his parent party, Shiva Sena. Source: Aarey residents.

“These forests don’t just belong to the humans, they belong equally to the trees, the animals and the entire ecosystem of the forest. No one thinks about these trees and animals, like the way we do. They are literally our family members. Now the Government is talking about ‘rehabilitating’ the residents living in these forests. But how will they rehabilitate these animals and the trees? This forest is their home too. [The] Government says Aarey is ‘not a forest’. You can convince humans by using violence or your laws. But how will you convince the trees and the animals, that this is not a forest?” said Prakash Bhoir, one of the leaders of the Aarey movement, and himself a resident of the Aarey colony.

“We are not grabbing anyone else’s lands, we are not asking [for] anything from anyone. We only want to protect our lands, our forests, and our culture. And this forest does not even belong only to us. It belongs to everyone in the city. The oxygen that these trees give out, is for everyone and not just us,” Bhoir added.

Prakash Bhoir addressing a meeting of the Aarey residents fighting against eviction and forest grab. Photo: GX.

The city of Mumbai is already facing a severe environmental crisis. Climate patterns have changed. Erratic monsoons, rain and water shortages, and multiple floods – all these have now become normal in the city. Central Pollution Control Board (CPCB) data from last year showed that the city’s level of pollution caused by particulate matter in 2018 was the highest in over 20 years. A 2018 survey report by the World Health Organisation claimed that Mumbai was the 4th most polluted mega-city in the world – only after Delhi, Cairo and Dhaka.

An Adivasi pada under siege

While the forests are being destroyed, the original inhabitants of these lands are being systematically deprived of basic requirements such as drinking water supplies and electricity connection in an attempt to force them to leave.

Navshyacha pada – one of the 27 Adivasi padas in Aarey forest, has 70 to 75 houses. In 1974, the Government transferred an entire chunk of land including the Navshyacha pada itself, to the Bombay Veterinary College. “In 1974, when they started the construction of the veterinary college, we also worked for the construction work as begari [slave] workers,” said a lady from the tribal community of the Naushyacha pada. People from the pada who worked for the college construction were paid Rs. 10 a day for working for 8 hours. “We thought we will get some job in this college and will earn some money. But later we realized that they basically took away our land and had no concern for our well-being. In fact, they are denying even our basic rights like water and electricity,” she continued.

Naushyacha pada now is sandwiched between the college campus, and its women’s hostel and staff quarters. There is no electrification along the forest road that leads to the pada from the main road. The residents have to depend on the College campus security checkpost to get entry into their hamlet. People from Naushyacha pada work as daily labourers in the Bimbisar-Goregoan and Jogeshwari areas. The working people and students have to rely on each others’ help to enter the pada in the evenings because of fear of wild animals. For the construction of the road to the hostel that passes through the pada, the authorities demolished 4-5 tribal houses. “We had to re-construct our houses by ourselves, after the demolitions during road construction. They never gave us any compensation,” she added. Eventually, the existence of the pada came under complete control of the Veterinary College – including dictating their access to basic needs like shelter, water and electricity.

Control over Housing

After coming under the control of the Veterinary College, the Adivasi community people were never allowed to build pucca [permanent] houses – till today. “They are not allowing us to construct pucca houses. We can’t bring cement or concrete inside as we now have to enter through their gate. They have posted watchmen at these gates, who don’t even allow to bring in materials like bamboos. If they see us with such materials, they stop us at the gate itself. We can’t even build toilets. Once we tried to bring four small bio-toilets but they did not allow us. Those toilets were for our children. We had to take out a protest march to the gate, to bring those bio-toilets in,” said one of the residents of the Naushyacha pada.

The authorities don’t allow these villagers to build pucca houses, mainly because in their imagination these people will be evicted from these forests sooner or later. “We will give you houses outside, they say. But why should we leave our space? Our generations have died in this land,” said people at the pada. Even though the villagers have been living here for generations, and are the original inhabitants of these lands, they are seen as “illegal encroachers” by the rest of the city and its Government. The Government has not even issued a “7/12 extract document” till date for hamlets like the Naushyacha pada. “7/12”, referred to in local parlance as ‘saat baara’ is a land deed that establishes ownership details of lands in the state.

Access to Electricity

The Veterinary College administration was, for a long time, refusing to provide an NOC to the community for getting an electricity connection. The Adivasi families were forced to ‘steal’ electricity connections from the college or its hostel. They could get electricity only during the night time. “Sometimes on Sundays we used to steal electricity in the day time, but they used to come and cut the wires,” said one of the community members. “There was light on the road but darkness in our houses, such was our condition,” she added. They were fighting for electricity since 2009.

Finally, in 2018 they decided to organise protest demonstrations under the leadership of Prakash Bhoir. They formed a union called the Adivasi Hakk Sanvardhan Samiti [Tribal Rights Assertion Committee]. They were contemplating filing a case against the college authorities under the Prevention of Atrocities Act if they don’t get the NOC. Finally the college administration yielded and gave them a NOC on June 3, this year. Even though community finally got electricity connections, their fight for other basic needs like water continues.

Access to Water

While the college and its hostels have tap water supply facilities, the Adivasi pada situated exactly between the two has to struggle for drinking water. Women from the pada have to walk till the gate of the college in order to get drinking water for the household. For other tasks such as washing clothes, for example, they are forced to use the water available in the nearest tabela [animal shelter]. Starkly, while the Adivasi pada struggles to access water, the college hostel and staff quarters are supplied water by a pipeline that runs right next to the pada. “Once we broke their pipe to get water but that did not work. We have to use dirty water from tabela by cleaning it at our home. Even the tabela people do not allow us to use that water. We have to go during the night time, often around midnight, to fill water to wash clothes,” said one of the residents. “We have to take a leave from work at times, and spend our whole day in bringing water,” said another resident.

The Adivasi Hakk Sanvardhan Samiti is now fighting to get tap water connections for the pada. During the rainy season, people from the pada earn their livelihood by selling vegetables they grow in their lands – this becomes impossible in other seasons because of unavailability of water. During such times, they have to depend on daily wage work for their livelihood.

Politics behind the Stealing of People’s Basic Rights

Since 2013, the state is trying to ‘rehabilitate’ tribal communities from Aarey to different SRA (slum rehabilitation) colonies. While some of the padas such as Naushyacha pada have resisted such evictions, others have been already dislodged. People from the Parjapur pada, for example, were recently rehabilitated to an SRA colony in Chandivali. “But now they are in trouble,” said Asha Bhoye, one of the residents of the Parjapur pada who resisted the move to take away her land and has filed a litigation against the Government.

MMRDA officials met with people from the Parjapur pada in 2013 and informed them that their houses will be demolished for the Metro project. They promised them that people will get houses and compensation for the trees on which their livelihood is based. They also asked them not to approach any ministry. “People thought that if we are getting proper rehabilitation, then why should we go to any office?” said Asha Bhoye, one of the residents of Parjapur pada.

The administration conducted a survey and decided on a date for the demolition. The demolition was carried out in three steps. Houses of those who were not ready for the deal were forcefully demolished. “When they came to demolish our houses and occupy our farmland, we questioned them, but they said this is the Government’s land. We are living here since generations. Since when it became the Government’s land, we don’t understand,” said Asha.

“Prove that you are an Adivasi, Prove that this is a Forest, Prove that this Land is yours!”

In order to get these SRA accommodations, the Adivasi residents were asked to produce ‘caste certificates’ proving that they are indeed Adivasis. Those who do not have such documents are left nowhere. In a truly bizarre and inexplicable move, the CEO of Aarey Dairy was called upon by the Court, along with the Project Officer of the Tribal Department of Borivali, to check the truthfulness of Adivasi identity claimed by the Adivasis of Aarey forest.

After the demolition of Parjapur pada, when the Adivasi residents went to ask the authorities about compensatory land as promised, they were told that “No Adivasi were living on that piece of land.” The authorities further claimed that there were no trees, and the land was vacant all along. Asha Bhoye and five others had to file a case to prove their ownership of land. Meanwhile, the construction work of Metro carshed is already underway at Parjapur pada.

Metro carshed construction work at Parjapur Pada. Photo courtesy: Satyabrata Tripathy/Hindusthan Times.

The Government does not even accept Aarey as a ‘Forest’. As a result, the Forest Rights Act therefore doesn’t apply here. “The Government even classifies barren lands at times as forests when it suits them, but ironically refuses to categorise Aarey as a forest. Isn’t this a forest?! We don’t care about what the Government papers say. Aarey is clearly a forest, and must be respected as such,” said Prakash Bhoir.

The City is snatching away everything from its Adivasi residents

The Adivasi padas in Mumbai stretch all the way from Dahisar to Mulund to Ghatkopar. This includes the national parks, Gorai, Malad, Andheri, Kandivali, Aarey Colony, etc. The biggest of these Adivasi communities are the Warlis. But there are also other communities such as Kokanal, Malhar Koli, Katkari, and Dawar.

People from most of the 222 padas across Mumbai have been forced into urban settings. Their lands have been taken away for ‘development projects’, and they have been forced into tall chunks of concrete called the ‘slum rehabilitation buildings’. Their traditional livelihoods have been taken away from them. However, it is not just a loot of their land and economy.

“Our Gods, our culture, language, art, paintings, songs, dances, festivals, our health – everything is being buried under the city’s urban landscape. If you visit our homes, you won’t find a single picture of any God. But our homes are filled with Warli art. This art is our form of religious and social expression. All that is going now because of this systematic conversion,” said Prakash Bhoir. Prakash Bhoir is a Warli artist himself, and now so are his children. Today’s artists are using their art to critique the metro project and related social-environmental impacts. “What you people convey using 7-8 pages of text, we do the same through one Warli art panel,” he added.

While 59 padas spread across Aarey, Gorai, the national parks, Malad, etc. still exist as Adivasi forest villages, the rest have already been urbanised. These padas don’t even look like Adivasi padas anymore. “Most of our people in Mumbai today are only Adivasis on paper,” said Prakash Bhoir.

The current generation of ‘rehabilitated’ families can no longer find enough space in the SRA buildings, and are basically homeless. Parjapur pada residents ‘rehabilitated’ to the Sakinaka SRA buildings are finding it difficult to stay in closed structures as they were used to living in the open space. “For example, many Adivasis from Aarey never went to school. Hence they don’t understand, or are scared of using the lift – this forces them to stay huddled on the same floor. This is having serious health impacts on their bodies,” said Asha.

Mumbai’s Adivasi people are being driven away from the forests in order to open up the forests to the entry of the urban economy and culture. The key reason for restricting Naushyacha pada residents from constructing pucca houses, or from getting electricity and water connections, is to ensure that they are not able to claim their natural ownership of the land. The Metro project is a door to settling urban people here. Metro Bhawan, and attendant economic establishments will come up.

“While the kaagzi [legal] battle goes on in its own course, we are determined to physically stay put on our lands, we won’t let go of the land and the forest. This is not just any battle, this battle is our duty. We are not fighting just for ourselves, we are fighting for the well-being of everyone in Mumbai. I have planted 500 trees in my pada. I sell the fruits and other produce we get from these plants. But note that I am not selling the oxygen that these plants are giving out. That oxygen is for free, and for everyone in the city,” Prakash Bhoir said.

The author is a researcher and social activist.