One of the self-aggrandizing popular discourse among the elite Bengali bhadralok is that Bengal is ‘casteless’ and ‘exceptional’ compared to other states regarding the caste question. It is not quite civil enough to bring up the talk about caste issues in the polite urban conversation in a tea shop or coffee house which is deemed as rude and provocative for a ‘gentle casteless society’. But two recent incidents of casteist assault, indicate the superficiality of the discourse of a ‘casteless Bengal’. Writes Sandip Mondal.

The uniqueness of Bengal politics is that caste is considered antagonistic to party politics at the state level. Caste never makes an election issue and caste-based political movements are virtually absent. Though it is composed of one of the largest Dalit populations in India and has significant experience of Dalit mobilization in the late colonial period, caste was never a determinant political category in the electoral mobilization.

But the recent two incidents of assault using casteist slur that took place – one in the police department and another one in a premium university in Kolkata itself, a city known for its so-called radical intellectual culture for those outside – again indicate the superficiality of the discourse of a ‘casteless Bengal’. News came out in a Bengali newspaper on June 28 that a constable used to abuse a senior police officer using casteist slur in the Koshba Thana near South Kolkata, incriminating his caste background. No action was taken even after formal complaints were made by the victims to the higher authorities of the Kolkata Police. The second case came out on May 20 on the harassment of an Assistant Professor in the Rabindrabharati University, who faced taunts on the basis of her caste affiliation. There was an outrage followed by the event among the scheduled caste professors and five professors quit in protest.

Are these ‘stray’ or ‘fringe’ incidents?

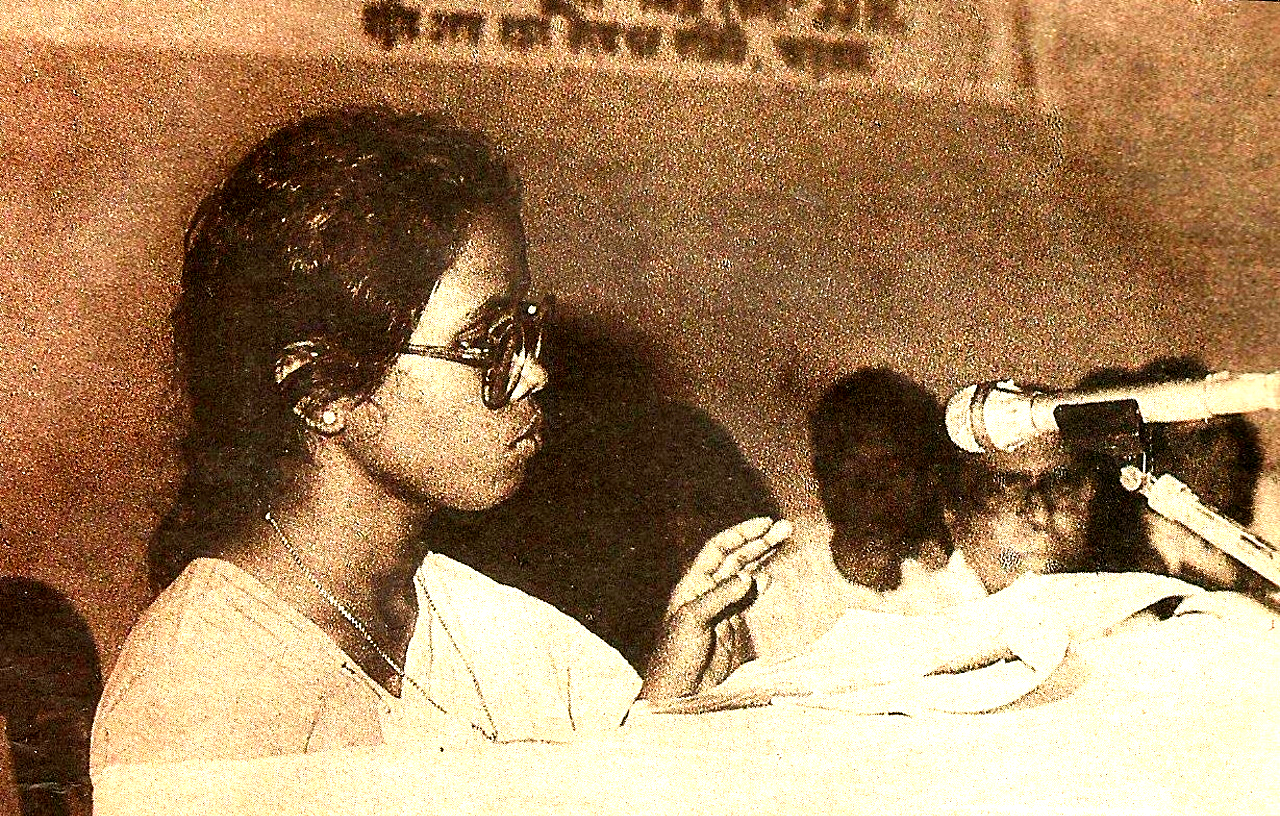

It can be construed that these two recent events are ‘stray’ or ‘fringe’ events that cannot represent the broader social picture of Bengal. But this is not true. The major blow to the ‘Bhadralok society’ came when Chuni Kotal – the first undergraduate degree holder from the Lodha Shabar tribal community – committed suicide in order to escape from persistent (caste-system based) anti-adivasi discrimination, in 1992. A well-known incident of caste discrimination came with the ‘midday meal controversy’ in 2004. It was reported widely in the newspapers that upper caste parents objected they would not tolerate their children sharing a common dining space with Dalit children, or being forced to eat food prepared by a Dalit cook.

A survey conducted by the Pratichi Trust in Midnapur, Birbhum, and Purulia districts in 2001, reported on caste-based segregation in classroom sitting arrangements in schools. In 2010, it was reported in Anandabazar, a wide circulated Bengali newspaper, that thirty lower caste families in a village of Murshidabad were prohibited to participate in puja festivities, particularly Durga puja, by the upper castes. In 2017, a case of social ostracism and forceful prevention of economic activities of a lower caste community named ‘Hari’ was reported in Paschim Medinipur for conducting an inter-caste marriage. These stories are no different from the stories that come in news reports from the rest of the country. These stories dismantle the proclamation that Bengal is ‘different’ from the rest of India.

Caste disparities in the socio-economic and political sphere of Bengal

A general overview of the magnitude of caste disparities in the socio-economic and political sphere of Bengal can be captured from large scale surveys like the Census of India and Indian Human Development survey. There is an existing paradox in the marriage practices of Bengal. On the one hand, the civility of the gentry class in Bengal claims their disdain for regressive structures of the caste system. On the other hand, most of the marriage arrangements take place on the line of intra-caste marriages. The magnitude of intra-caste marriage is 90.6 percent which is even more than the national average (Calculated based on IHDS-II, 2012).

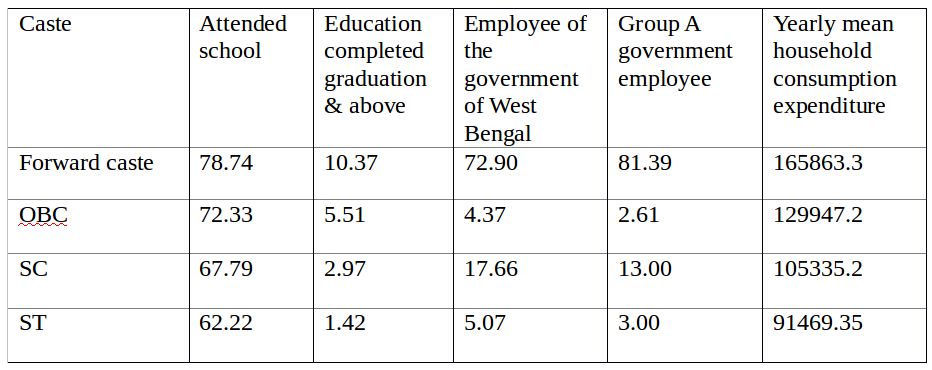

If we shift our focus to education, a gap of 10.95 percent can be observed in educational attainment between forward castes and scheduled castes, where 78.74 percent of forward castes ever attended school compared to the 67.79 percent for Dalits (Table No. 1). An observable difference between SC and forward castes exists in higher education also, where 10.37 percent population from forward castes reached graduate and above levels compared to only 2.97 percent for scheduled castes (Table 1).

Education acts as a multiplier in social mobility and getting a job in government sector. The distribution of government employees across social groups reflects that a sizeable proportion of government job is occupied by the forward castes which constitute 72.90 percent of the total government employees (Table No.1). In the Group A government jobs which have more emoluments and need higher education, 81.39 percent employees are from forward castes compared to only 13 percent from the scheduled castes. The scheduled castes are also unfairly distributed even in the Group D and Group C jobs. The fact that representation of scheduled castes is less than the officially stipulated 15 percent in the Group A jobs, indicates insufficient implementation of reservation policy. Income disparity can also be found along the caste axis where yearly mean household consumption expenditure is Rs 1,65,863.3 for forward castes whereas it is Rs 1,05,335.2 for the lower castes.

Table 1: Socio-economic parameter among caste groups. Source: Calculated by author from IHDS-II, 2012 and Report of the staff census, Government of West Bengal, 2015.

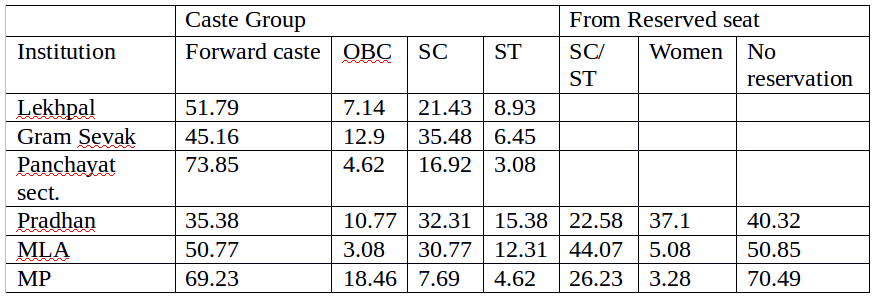

Table 2: Caste-based representation in the political institution. Source: Calculated from IHDS-II, 2012.

The forward castes are also the most privileged in the political terrain of Bengal. Most of the political institutions are with no reservation, and are hegemonized by the forward castes. As there is no reservation in institutions like Lekhpal, Gram Sevak and Panchayat Secretary, forward castes are dominant in those bodies. On the other hand, the presence of people from SC, ST and OBC castes in the posts of Panchayat Pradhans, MLAs and MPs are only restricted to the number of seats reserved for them. There is hardly any more number of people from these communities in such posts than what is officially required. All these indicate that the political space in the state is after all not so liberal that Dalits are getting entry into the unreserved constituencies.

Subsumption of questions of Caste in post-partition West Bengal

It is quite vividly evident that caste does matter, and matter deeply, in the socio-economic and political landscape of Bengal. But these caste questions do not act as a basis for political mobilization. In the late colonial period of undivided Bengal, the caste-based political mobilization of the Namasudra and Rajbanshis acted as major impediments to the hegemonization of the upper castes. But after the partition, the question of caste was subsumed under phrases such as ‘partition victim’ or ‘refugees’. These categorizations could be easily absorbed into the left liberal ideologies under the dominant discourse of ‘class’. Under the long rule of the Left Front regime, the hegemony of the party was so strong and pervasive that its structures and institutions monopolized and stifled the autonomy of every social body and community.

As a result, upper caste hegemony became so strong through the party that Dalits could not even imagine their own autonomous political existence. But this does not mean that caste has disappeared from Bengal or that it is unique from other states regarding the caste question.

The author is a research scholar at Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi.

Feature image: Chuni Kotal – first woman graduate from Lodha Sabar community, West Bengal. Source: Internet.

Thanks for the very informative article