The “irrational exuberance” or the state of mania that affected much of the world in the mid 2000s also touched India. As the country enjoyed high economic growth, numerous business enterprises began an aggressive expansion spree on the back of bank credit. Corporate borrowers could keep on taking loans from banks and increasing debt safe in the knowledge that losses would be borne by the taxpayers while gains would be theirs alone. But this comes at a cost – the near collapse of the public banking system with ripple effects destabilising the entire economy. Sushovan Dhar writes.

Modi’s election – Euphoria for growth

According to IHS Markit, a London based information provider, India is going to overtake the UK, its former colonial ruler, to become the world’s fifth largest economy this year and is projected to outdo Japan to feature at the second position in the Asia-Pacific region by 2025. Modi’s re-election at the helm of the Indian government, last month revived hopes from all sectors of the industry. To celebrate his victory, the Indian stock market indices, Sensex and Nifty, rallied to record heights expecting more business-friendly measures. The confidence is high that economic growth, corporate earnings and a flurry of policy initiatives is forthcoming despite scepticism from various corners. However, the questions around the mounting Non-Performing Assets (NPAs)* of the banks, the rising corporate debt, the low corporate earnings and the global economic uncertainty are some of the issues that continue to haunt the Indian economy.

Corporate debt

While it might be a bit too premature to compare the Indian situation with the Asian crisis of 1998 or the global crash of 2008, the situation doesn’t look comfortable either. Earlier, in 2017 a report by Credit Suisse drew attention to India’s corporate debt problem. The report revealed that about 40% of India’s corporate debts are with firms that are unable to even earn enough to pay the interest costs. It is important to understand that corporate loan repayments are structured in such a manner in which the capital and interest is paid back in a series of regular payments to the creditor, i.e. an annuity. The annuity is configured in a way so that the first few payments only cover the interest, and the later payments take care of the the capital. It is for this reason that the data about the above 40% debt is most striking. It implies that a huge amount of firms are in a downward spiral. Possibly, they would be always trapped in the interest-paying phase of the annuity, never reaching the capital-paying stage. As a result, such sums of money that these firms are unable to repay ought to be written off by the banks and declared as NPAs. The Credit Suisse report further says that out of the $ 530 billion total debt, almost two-thirds of it is with firms that have not covered interest payments for at least 11 of the past 12 quarters. About 30% of the total debt is with firms that have reported losses.

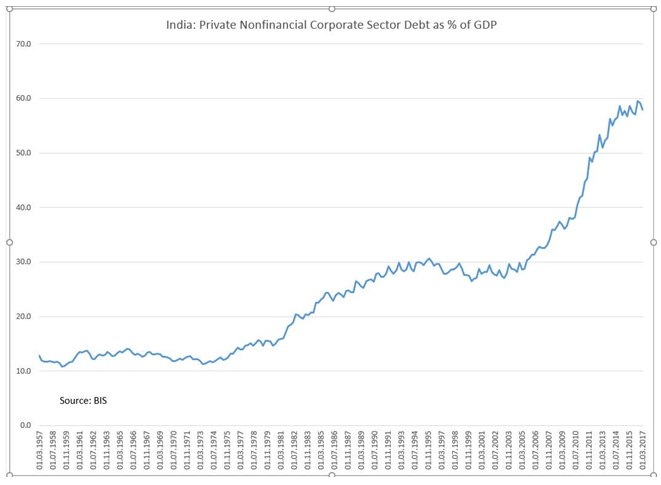

Indeed, data available for the last 60 years shows that the corporate debt as a percentage of GDP is growing steadily in India. And, the growth is steep since 2002-2003.

Table 1. Growth of Corporate Debt in India

According to McKinsey Global Institute:

The total debt of non-financial corporations, including bonds and loans, has more than doubled over the past decade, growing by $37 trillion to reach $66 trillion in mid-2017, or 92 percent of global GDP. This growth is nearly equal to the increase in government debt, which has received far more attention. In a departure from the past, a large share of the growth in corporate debt has come from developing countries, and in particular China, which now has one of the highest ratios of corporate debt relative to GDP in the world.

The report also states that:

Bond issuance by companies in China and other developing countries has soared. The value of China’s non-financial corporate bonds outstanding rose from $69 billion in 2007 to $2 trillion at the end of 2017, making China one of the largest bond markets in the world. Outside China, growth has been strongest in Brazil, Chile, Mexico, and Russia.

Globally, the issue of burgeoning Indian corporate debt has received much less attention as compared to the Chinese corporate debt which hovered around 147% of its GDP in mid-2017. It might have not scaled those levels like Luxembourg, Hong Kong, Ireland, the Netherlands, Belgium, Sweden, China, France, Norway, Switzerland or others where the quantum of corporate debt is more than 100% of the GDP but, the signs are troubling. Also the US corporate debt which stands at $9 trillion debt is a potential threat if interest rates continue to rise and the economy weakens. Although Wall Street bond experts would like to make us believe that the issue would be contained in the next one year, at maximum, the financial indicators are not that reassuring. According to Securities Industry and Financial Markets Association data, the total US corporate debt has swelled from nearly $4.9 trillion in 2007 as the Great Recession was just starting to break out to nearly $9.1 trillion halfway through 2018, quietly surging 86 percent. No wonder that a section of commentators and analysts consider this as a ticking time bomb.

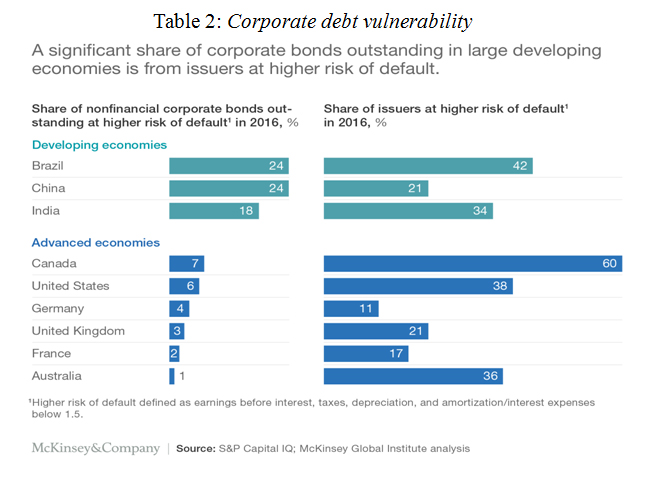

In India as well, the corporate debt is spiraling up and it might not be long when it catches up those levels. Metal, power, and telecommunications are the sectors that account for 40% of the unserviceable debt i.e. debt with companies that can’t even pay interest. This is especially worrying because these three sectors provide inputs to several other sectors and are also responsible for providing livelihoods to many people. A meltdown in them will have ripple effects throughout the economy. According the same report:

Even at today’s low interest rates, 20 to 25 percent of corporate bonds in Brazil, China, and India are at higher risk of default (issued by companies with an interest coverage ratio below 1.5). In our simulation of a 200-basis-point rise in interest rates, that share could increase to 30 to 40 percent.

Corporate bonds are debt securities issued by private and public corporations. Companies issue corporate bonds to raise money for a variety of purposes, such as building a new plant, purchasing equipment, or growing the business. When one buys a corporate bond, one lends money to the “issuer,” the company that issued the bond. In exchange, the company promises to return the money, also known as “principal,” on a specified maturity date. Until that date, the company usually pays you a stated rate of interest, generally semi-annually. Bank interest rates and bond prices have an inverse relationship; so when one goes up, the other goes down. Lower interest rates means higher demand for bonds and hence a rise in bond prices. However, the opposite happens when interest rates rises and there is a rush to sell of bonds and consequently bond prices fall. In such a scenario, the corporate already under massive debt and falling profit are at higher risk to default.

Let us look at the story of Jet Airways which had consistently been one of India’s top three airlines over the past decade. It had the largest market share in the growing Indian aviation industry and also flew to several international destinations. Abu Dhabi’s Etihad Airways PJSC owned 24 % shares of Jet Airways. The debt-ridden aircraft has gradually hit the ground in the last six months and is now completely stranded. The airlines has a net debt of INR 72.99 billion ($1 billion) and defaulted on loans that were due by December 31, 2018 and has been unable to pay its staff and lessors. In April, a senior technician with Jet Airways committed suicide in Maharashtra’s Palghar district due to depression. He was a cancer patient, and was under severe economic crisis because of not having been paid salary for several months.

Let us look at the story of Jet Airways which had consistently been one of India’s top three airlines over the past decade. It had the largest market share in the growing Indian aviation industry and also flew to several international destinations. Abu Dhabi’s Etihad Airways PJSC owned 24 % shares of Jet Airways. The debt-ridden aircraft has gradually hit the ground in the last six months and is now completely stranded. The airlines has a net debt of INR 72.99 billion ($1 billion) and defaulted on loans that were due by December 31, 2018 and has been unable to pay its staff and lessors. In April, a senior technician with Jet Airways committed suicide in Maharashtra’s Palghar district due to depression. He was a cancer patient, and was under severe economic crisis because of not having been paid salary for several months.

Earlier in 2012, Kingfisher Airlines, another glamorous high-flyer, founded by beer tycoon Vijay Mallya, ended operations after failing to clear its dues to banks, staff, lessors and airports. The stories of Kingfisher and Jet are symptomatic of what is happening to corporations that were perceived to fly India into the new century of prosperity.

Growing NPAs

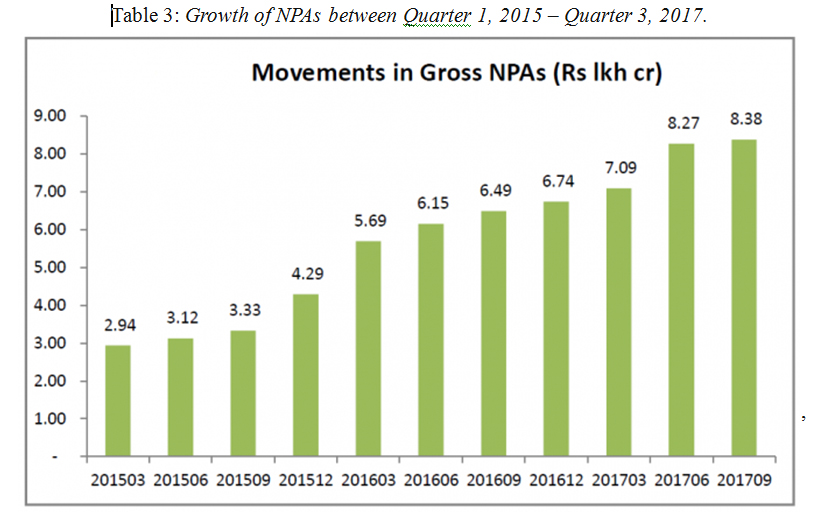

The crisis in the banking sector is a manufactured one, where the commercial banks have been forced to perform large scale lending to development projects and to corporate, which has created an NPA of more than $ 150 billion till the end of 2018. Since 2015, NPAs have been increasing and today they even threaten the survival of the public sector banks. The very fact that 82% of NPA is that of corporate loans tells the real story. While the financial experts will ascribe the ‘root cause’ of this crisis to bad lending policies and inadequate due-diligence, collaterals, and recovery system, it is amply clear that this huge NPA is the result of a criminal nexus between corporates, top managements of the banks, bureaucrats in the finance ministry and the politicians. It is this unholy nexus which is bleeding the banks of peoples’ hard earned savings deposited with them.

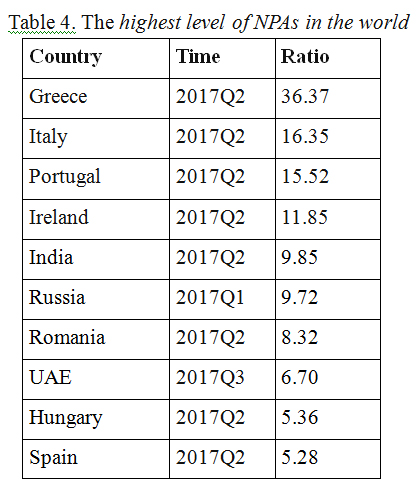

According to the second-largest credit rating agency in India, CARE Ratings, India’s NPA ratio is fifth highest in the world only after Greece, Italy, Portugal and Ireland. India’s NPA ratio stands at 9.85% and the Reserve Bank of India’s (RBI) Financial Stability Report states that this ratio is set to deteriorate to 12.2% by March 2019, which would ‘promote’ India to the fourth position, ahead of Ireland. The four major developed economies in the world like US, UK, Japan and Germany had NPA ratios of less than 2%. Within the developed countries only France had a higher NPA ratio of 3.41%. In India, 11 public sector banks fall under the prompt corrective action category, implying that the poor quality of their balance sheets have to be addressed immediately to avoid potential bankruptcy.

Several commentators have raised the question whether the “NPA black hole” could “suck in the country’s entire banking system.” A systemic collapse can’t be ruled out. Already, many banks are not in a position to lend money leading to an anemic credit supply from the country’s weak banking sector. The total disbursement of loans by public sector banks in 2016-17 was 69% of the total loans.

The troika of politicians, bureaucrats and the capitalists form a vicious nexus that controls these banks. Indian banks have written-off a whopping INR 1,56,702 crore of NPAs during the nine-month ended December 2018, taking the total loan write-off to over INR 7,00,000 crore ($ 101 billion) in the last 10 years, according to figures revealed by the RBI. A large chunk of the write-offs, or almost four-fifth of the total amount written off in the last 10 years, have accrued in the last five years since Narendra Modi came to power in 2014. This grotesque magnanimity to the corporates is being attempted to be compensated by recapitalisation of banks through public funding, which in other words means that the ordinary Indian people would be bailing out the banks that are still being plundered by the corporates. It is nothing but a vicious example of crony capitalism, where those with connections to the politician-bureaucrat mafia “laugh their way to the bank.” The $1.77 billion Punjab National Bank (PNB) scam, possibly the biggest financial chicanery to have hit the Indian banking sector, is a perfect example of this trend.

While many advocate privatising the public sector banks as a panacea of all evils, private banks in India face huge problems too. The well-known private sector banks like the ICICI Bank, Axis Bank and Yes Bank had their share of NPAs as well. In the recent past, we have seen the glamorous top bosses of these banks forced to resign, unceremoniously.

NBFCs face default

The contagion is not just limited to the banks but has also spread to Non-Banking Financial Companies (NBFC) that has emerged as a powerful entity in recent years, growing at 25-30% in the last five years. NBFCs lend and make investments and hence their activities are akin to that of banks; however there are a few major differences: 1) NBFC cannot accept demand deposits; 2) NBFCs cannot issue cheques drawn on itself.

It seems that the NBFC party is over for now. This will have a big spill over effect on the banks because they were betting on NBFCs. According to reports, banks have given huge loans to NBFCs. The default of the Infrastructure Leasing and Financial Services (IL&FS) has sent shudders to the Indian financial system. Dewan Housing Finance Limited (DHFL), another NBFC, with a focus on housing finance has reportedly missed interest payments of INR 960 crores ($ 138.57 million). Subsequently, DHFL faced a series of downgrades by rating agencies over the past two months. This would make it more difficult for DHFL to access loans from financial institutions, both domestic and foreign. A series of banks led by Yes Bank and four other public sector banks have big exposure to DHFL. The development will have a far-reaching impact on the entire financial sector. Also many NBFCs, housing finance companies, real estate companies, auto and small-and-medium enterprises will have to bear the brunt. Such is the dire state of affairs that the Government is reportedly on the verge of cancelling licenses to 1,500 smaller non-banking finance companies because they lack adequate capital.

Around a quarter of the total NPAs in India come from a motley crew of such shadow banks that have grown exponentially. These are quasi-unregulated and they lend in particular areas such as real estate. As they are usually prohibited from taking deposits, they depend solely on loans to fund themselves. Likewise, in China, a crackdown on its $10 trillion shadow banking market is contributing to a rise in defaults.

Conclusion

The “irrational exuberance”** or the state of mania that affected much of the world in the mid 2000s also touched India. As the country enjoyed high economic growth, numerous business enterprises began on an aggressive expansion spree on the back of bank credit. Even, one of the India’s most renowned corporate house fell prey to the dominant ‘exuberant spirit of the time’. Tata Steel’s $12.1 billion purchase of Corus in 2007 remains the poster child for this recklessly extravagant era. Investor enthusiasm drove asset prices up to levels that aren’t supported by economic fundamentals. Needless to say, this purchase — like many others 10 years ago — has turned out to be an unmitigated disaster. Tata Steel’s European operations have had a torrid time since the acquisition. Tata Steel’s Indian operations have accounted for a lion’s share (60 to 96 per cent) of the company’s total profits between FY08 and FY11. In FY10, the Indian steel business reported net profits of Rs 5,000-crore while the consolidated losses from Chorus operation was over Rs 2,000 crore. The India operation’s gross debt moved from Rs 18,000 crore in FY08 to Rs 28,000 crore at the end of FY11, mainly on account of borrowings to fund Chorus.

The problems with big firms with huge debts will result in even greater troubles for banks. Until very recently, lenders enjoyed little legal protection. Banks could rarely recover loans from those with political connections. Forgiveness and haircuts were the norm when things went south for big borrowers. Borrowers could keep on taking loans and increasing debt safe in the knowledge that losses would be ultimately borne by the taxpayers while gains would be theirs alone. They still enjoy the ‘right’ to privatise the profits and socialise losses but this comes at a cost – the near collapse of the public banking system with ripple effects destabilising the entire economy.

Though it has still not outgrown into a full grown crisis, a sell-off in global markets could easily trigger a new wave of panic. This growing contagion of corporate debt that is spreading over to banks and NBFCs is most likely to be a prime element in the next financial crisis. Companies getting overstretched on cheap credit and with falling profits, the mountain of corporate debt has all the potential to trigger an economic crisis in India and many other parts of the global South like its peers in the North.

Footnotes:

* Non Performing Assets (NPA) or Non Performing Loans (NPL) refers to a classification for loans or advances that are in default or are in arrears on scheduled payments of principal or interest. In most cases, debt is classified as nonperforming when loan payments have not been made for a period of 90 days. While 90 days of nonpayment is the norm, the amount of elapsed time may be shorter or longer depending on the terms and conditions of each loan.

** “Irrational exuberance” is the phrase used by the then-Federal Reserve Board chairman, Alan Greenspan, in a speech given at the American Enterprise Institute during the dot-com bubble of the 1990s. The phrase was interpreted as a warning that the stock market might be overvalued.

The author Sushovan Dhar is a political activist.

Cover image courtesy to PYMNTS.com