With the destruction of the Bombay mills and class struggle of the mill workers, the city and its politics took a decisive turn. Post-80s Bombay reeled under communal violence, controlled by the Brahman-Maratha-Kayastha caste combine. The industrial capitalist class evolved into a powerful financial mafia, with real estate as one the chief new economic activities. In the absence of organised working class resistance, struggles for a classless and casteless society were pushed back by the politics of Maratha identity, Hindutva and communal attacks on the city’s minority populations. The concluding part in the series by Arati Kade and Tathagata Sengupta. You can read the earlier parts here: Episodes One, Two, Three, and Four.

Episode 5: Mumbai and its Working class Today

The destruction of the Bombay mills and class struggle of the mill workers, fundamentally changed the city and its politics. Post-80s Bombay reeled under unabated communal politics controlled by the Brahman-Maratha-Kayastha caste combine. The early industrial capitalist class soon evolved into an extremely formidable financial mafia, with real estate development as one the chief new economic activities. Many of the mill owners shifted their factories to neighboring Gujarat. And tand under the mill began to be valued as gold.

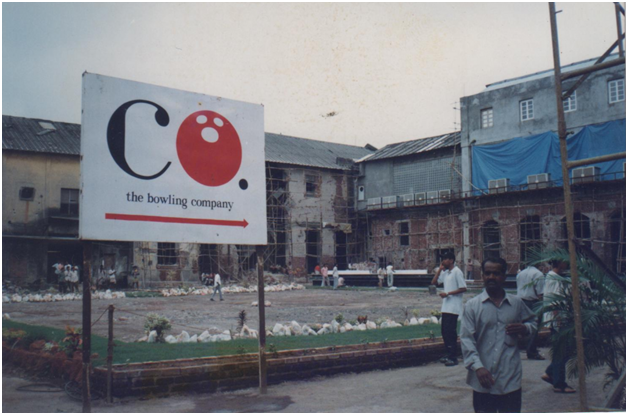

Legal manipulations were engineered by the politicians to ‘redevelop’ the mill lands. Fancy highrises started coming up over these lands, and money started pouring back in for the mill owners and their partners. Even Datta Samant was elected to the Parliament as an MP. Today, Kamla Mills and Empire Mills – the epicentre of Dr Datta Samant’s agitation – have turned into shining office complexes, hosting news and media organisations like Times Now and CNBC TV18.

In a absence of organised working class resistance, struggles for a classless and casteless society were parallel pushed back by the politics of Maratha identity, Hindutva and communal attacks on the city’s minority populations. Several dalit leaders such as Ramdas Athawale, Namdeo Dhasal and Raja Dhale were co-opted by the Congress-NCP-Sena power lobbies. Shiv Sena, over the years, established tight control over the city’s working population. The BJP would finally use the Sena as a vehicle to anchor themselves in the region’s politics, and now we are here in today’s Maharashtra.

Major riots broke out in Bombay in 1992-93, following the Babri Masjid demolition in Ayodhya. Shiv Sena goons attacked Muslim households in Pratikshanagar, and soon the riots spread through the city. Girangaon was one of the chief targets of the rioters and Muslim worker families were specifically targeted. “During the ‘92 riots, we were trying to protect Muslim families. My husband brought one Muslim family to our home, I hid some Muslim women in the attic of our chawl. Shiv Sena party workers were waiting outside, and they had a doubt [sic] that there are Muslims inside. At around 4 o’clock in the morning, I could finally take those women to the railway station. I gave them my sari and put bindi [coloured dot typically work by Hindus] on their forehead,” said CPI activist Com. Parvati Bhujbal.

Though Left political workers tried to oppose the riots, they were too weak to effectively control the situation. CPI worker leaders like Narayan Gadre and GL Reddy worked tirelessly to campaign against communal clashes. Narayan Gadre was renamed “Narayan Mullah” in the Shiv Sena graffitis. GL Reddy, who deposed before the Krishna Commission enquiry and testified that the riots were engineered by the Shiv Sena, was also attacked. Though the CPI still had a few corporators and legislators, mainly from the industrial constituencies, the riots dealt a final death blow to mainstream Left politics in the city. Mumbai politics has since been dictated by the Sena-Congress-NCP-BJP quadrangle. The city’s minority population has been summarily ghettoised over the decades, and incarcerated under draconian laws and false accusations.

Cartoon drawn by Bal Thackerey as a cover for his magazine, Marmik, on the issue of closing down of the mills. 1970. Source: Internet.

Over the years to come, lines between the business mafia and the political elite were blurred more easily than ever before. The BJP made inroads into the state riding on the Shiv Sena. A huge number of the hitherto organised industrial workforce was converted overnight into daily wage labourers. Daily life routinely featured slum demolitions, unmitigated environmental destruction in the name of big infrastructure, and rampant corruption laced with frequent political assassinations – in other words, modern-day Mumbai.

Bal Thackeray was not solely a hired goon for the capitalists and mill owners of Bombay. He did not operate based on the particular interests of specific capitalists and industrialists, although Thackeray was often the point person for individual capitalists like Bajaj, and companies like Larsen & Toubro, Parle, Maniklal, etc. when it came to ‘sorting out’ workers-related issues at their factories. All these plants had active Left unions.

Source: Shekhar Krishnan.

But Thackeray goes far beyond these individual cases on his journey to eventually becoming ‘Maharashtra’s patriarch.’ Immediately after the Shiv Sena was formed, Thackerey formed its “workers’ wing”, the Bharatiya Kamgar Sena that was to replace the Leftist trade unions. The Bhartiya Kamgar Sena would keep other unions out of the factories, in return for employment of the Marathi speaking Shiv Sena supporters. These new employees were described by the workers as ‘goondas’, brought in specifically to destroy the workers’ movement. The aim of the Bhartiya Kamgar Sena was clearly mentioned in Marmik on 11 August 1968, “To protect the workers from being exploited by the communist trade union”. As is natural for a group like the Shiv Sena which came up precisely in order to challenge progressive anti-caste and anti-capitalist politics, their brand of Hindutva today is a classical representation of the convergence of general interests of caste and capital.

Source: Shekhar Krishnan.

Thackerey’s project was not just to eliminate political leaders, but went much deeper than that. Thomas Blom Hansen writes in Wages of Violence about Thackerey’s liberal use of anti-Brahman language and symbolism from Jotirao Phule [Thackereys are themselves Kayasthas]. He also reports that CPI leader Dange was once invited to share the dais with Thackeray, to tremendous applause. And that the ‘socialist’ George Fernandes was a family friend of the Thackeray clan. These anecdotes are key pointers to the fact that Thackerey’s mass politics ran much deeper than what’s expected of a “fringe” vigilante group. The success of Shiv Sena and collapse of the great unions marked a turning point in India’s labour history. This period saw fundamental changes in the country’s industrial labour relations, specifically the relationship among business, politics and labour. Till the 1970s, Bombay’s organised sector was the city’s predominant employer. But over the 80s, all that changed.

Erstwhile mill complexes being converted into expensive malls. Source: Shekhar Krishnan.

Today the areas of Worli, Parel, Byculla, and Cotton Green in Western and Central Mumbai, which were once a political fortress to lakhs of workers, have been converted to lofty high-rises and commercial complexes fetching lucrative money for developers. “Girangaon [literally translating to ‘land of the textile workers’] with the prime land of the mills — a total of 600 acres — now sees a proliferation of luxury apartments, malls and commercial spaces. There is no regulation as far as land usage is concerned. Jobs are not created either … This is no longer a working-class city. There is a growing sense of alienation among working-class youths who have failed to land a job,” writes Meena Menon while describing her book titled “One Hundred Years One Hundred Voices” – a precious anthology of the Bombay Mill strikes.

“Being a melting pot of different cultures, brought together by the mills, the city acquired a vibrant community life. During Ganapati festivals, along with performances of Tamasha and Dashavatar from Konkan and Ghat regions of Maharashtra, there would be shows of Yakshagana from Karnakata and puppetry from Andhra Pradesh. That cultural exchange is almost over,” she adds.

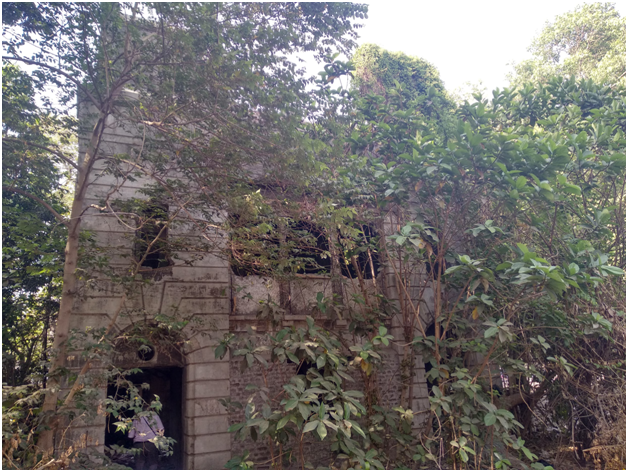

In today’s Mumbai, torn to pieces among linguistic and ethnic identities, the shut-down mills have been converted into fancy shopping malls. And in the midst of all that jazz, abandoned and decrepit empty godowns with collapsed walls and roofs, and rail tracks peeking out from underneath today’s concrete roads, that once connected those godowns to the port area further south, stand as unrelenting reminders of the murder of the city’s powerful working class, their aspirations, dreams and their struggles.

Railway tracks that once connected cotton warehouses around mill areas to the docks in south Bombay, largely buried under today’s roads. Photo: GX.

“I took VRS in 2003. The State law was passed in 2000 stipulating housing as compensation for Voluntary Retirement. But the RMMS sat on this and prevented the information about this law from reaching the workers. We fought in court to get the law finally implemented,” said Com. Prakash Bagave. It is because of the work of Bagave – one of the veteran leaders of the Girni Kamgar Union – that housing colonies for mill workers subsequently came up in many of the closed mill compounds. He began working in the mills in 1976. His father also worked as a girni kamgar, and was removed from his job on allegations of being a “Laal Bawtewala”, during the strikes of 1972.

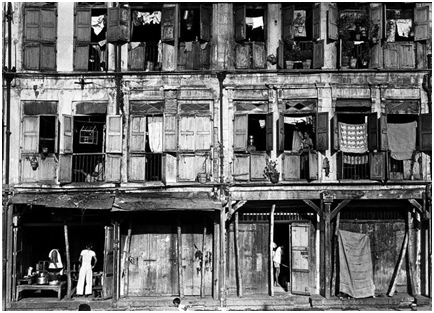

Chawls in Mumbai came up largely from the beginnings of the 20th century, to house the huge number of migrant workers who came to the city as workforce for the cotton mills and docks. Source: Internet.

But the struggle is still on. Com. Bagave alleged that the compensatory housing that was to be meant for the typical worker in the mills, was in effect captured by worker leaders who were close to the administration, mainly from the clerical and managerial sections of the mills. Many of these worker leaders have allegedly co-opted the struggle for demanding housing for retired mill workers. “Nothing has changed,” he said at the end, “Earlier it was Congress which destroyed Bombay’s industry, now it is Narendra Modi who is doing the same through contractualization and deregulation. Even the legal basis for Modi’s policy of contractualization of labour is the Contract Labour Act of 1970 – it was drafted by the Congress, and not the BJP.”

References:

The Rise of Business Corporations in India, 1851-1900 – A Book by Radheshyam Rungta

“Strike by 2.5 lakh textile workers in Bombay’s 60 mills to complete a year” – From a January 1983 India Today issue

“Datta Samant: A lion who prowls the embattled frontier between labour and capital” – From a February 1982 India Today issue

Ripping the Fabric: The Decline of Mumbai and its Mills, by Darryl D’Monte, published by Oxford University Press, New Delhi, 2002

“Builders grabbed Rs17,000-cr plot, trade union leader’s son tells HC” – An example of closed mill land acquired by the real estate mafia

The Murder of the Mills: A Case Study of Phoenix Mills – A Report by the Girangaon Bachao Andolan and Lokshahi Hakk Sanghatana, April 2000

The Long Haul: The Bombay Textile Workers Strike of 1982-83 – A book by Rajni Bakshi

Remembering Dalit Panthers on the Death Anniversary of their First Martyr – A report on the Dalit Panthers and murder of their leader Bhagwat Jhadav

Workers’ Politics and the Mill Districts in Bombay between the Wars – Rajnarayan Chandavarkar

Narayan Meghaji Lokhande-The Father of Trade Union Movement in India – Nalini Pandit

Cover image: United Mill, Parel District. Source: Flickr