Mumbai – India’s bustling “Financial capital”. Carefully hidden beneath the city’s hustle, bustle and ruthlessness, its money and politics – lies a chilling history of the city’s cotton mill workers and their century-long struggle that once took the city by storm. Episodes One, Two and Three in the series spoke about the history of the Satyashodhaks, Dr. BR Ambedkar, Com. SA Dange’s and Com. Krishna Desai and the Girni Kamgar Union’s prolonged militant organising of Bombay’s mill workers. In this Fourth episode, the authors, Arati Kade and Tathagata Sengupta write about the 1980s – the decade that finally saw the fall of the workers’ movement, with the last prolonged strike under the leadership of a trade-unionist Doctor – Dr. Datta Samant that coincided with the winding down of the industry itself. The workers’ movement in the city was pushed back heavily by the city’s corporate class and their political-ideological partners, and the stage was being set for the ‘90s when the city would be set on fire by these emboldened ruling forces.

Episode 4 (1980s): Dr. Datta Samant, the Congress, and the beginning of the end

By the 1980s, leftist parties in Bombay had become weak and the number of mill workers in the city had gone up to around 2.5 lakhs. However, working class militancy continued. In the absence of a Left leadership capable enough to lead and organise the workers’ movement, the Congress-run state government and the Rashtriya Mill Mazdoor Sangh (RMMS) affiliated to it, controlled the labor relations in the city. RMMS was the only “union” recognised by the mill owners and the administration, despite the Industrial Disputes Act of 1938. While the Girni Kamgar Union would organize strikes against the management, the RMMS would be the signing authority on the settlement as the workers’ legitimate representative. Many struggling workers were termed as “Laal Bawtewaale” [One with the Red Flag], and removed from work on grounds of being a Communist. These were workers who were agitating not just for fair wages, but also against increasing mechanization and loss of jobs in the textile industry.

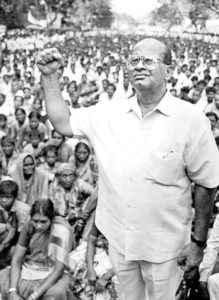

Around this time, a large section of the frustrated workers went to an ex-Congress trade unionist Dr. Dutta Samant. Samant was a doctor by profession, and a member of the Congress party. He spent years treating workers in the city and the occupational diseases that they suffered from. This exposed him to the horrifying conditions of the city’s industrial worker, and he began taking part in trade union activities. He had since quit Congress and become famous for leading successful struggles against industrial factory management, for example in the Godrej Mills. As a leader of the Premier Automobile workers, Samant had acquired a wage raise of Rs. 500 [Adjusting for inflation in the value of the rupee, this converts to around Rs. 1800 in today’s terms]. At this time, the Bombay mill worker’s monthly salary itself was around Rs 550 for men and Rs 330 for women — for a ten-hour work day, 6 days a week.

In 1982, large sections of the Bombay textile mill workers went to strike under Dutta Samant’s Maharashtra Girni Kamgar Aghadi, against the Mill Owners’ Association and the Congress-affiliated official trade union RMMS. The communist controlled Girni Kamgar Union had to support Samant’s leadership, though he was throughout seen as “a Congress agent” or “Congress fraction” by some sections.

Under his leadership, around 2.5 lakh mill workers of Bombay went on the historic general strike that was never lifted and technically continues even today. Though the expectation was that the strike would last for a few months, as was usual, it went on for a year and a half. With the Left already cornered, and with Samant’s Congress affiliation guaranteeing natural limits on his class politics, Bombay’s bourgeois political class decided to go for the final blow to the city’s working class politics.

They never reopened the textile mills again. After a year long strike that began in 1982, the workers’ families finally gave up, though not without a fight. A large number of workers’ families had left the city due to the prolonged strike, and in parts because of a call given by Samant himself sending struggling workers back while he manages the strike in the city. “We didn’t even have money for food, we left for our villages then,” said one of then striking workers. Though this weakened the struggle considerably, the workers who remained fought. “Aisa nahi, humne bhi maara unhe. Nare Park [Parel] me hum logon ne patthar se maara tha Bal Thackerey ko… [We hit them too. In Nare Park in Parel, we threw stones at Bal Thackerey…],” said another erstwhile mill worker. However, the Shiv Sena did manage to dent the weakening movement with constant backing by the ruling Congress and its police administration. Worker by worker, the Communists were removed from their jobs. “I had to fight a legal case for 14 years to get back my job,” said Prakash Bagave, one of the Kamgar Union leaders. One by one, the Shiv Sena and Congress took back the mills and then destroyed them. It was well known that Shiv Sena operated as Congress’ ‘B team’. The Bharatiya Kamgar Sena and the RMMS worked together to break the back of the workers’ struggle. “After the death of Krishna Desai, news reports came out alleging Indira Gandhi had paid 2.5 lakh rupees to Bal Thackerey for breaking strikes,” said Bagave.

The Kalachowki police station, infamous for cracking down upon the striking mill workers and their families. Photo: GX

The 1982 strike is technically still going on, because it was never officially called off. By 1984 however, the strike had effectively collapsed with Samant winning no concessions. The mill owners gradually started shifting their mills to the outskirts of the city – at places like Bhiwandi and Malegaon. Many mills shifted to the neighboring state of Gujarat. Over the years, mechanized big composite mills got replaced by smaller power-looms and separate smaller units for dying, for weaving, etc – converting a once organised advanced industrial workforce into unskilled, unorganised daily wage and contractual labour force.

Samant remained popular within a network of trade union activists, and was elected on an independent, anti-Congress ticket to the 8th Lok Sabha in 1984; an election that was otherwise swept by the Congress under Rajiv Gandhi. He would organise the Kamgar Aghadi, and later the Lal Nishan Party, and remain active in trade unions and communist politics through the 1990s. On 16 January 1997, Samant was murdered outside his home in Powai, by contract killers who fled on motorcycles.

Com. Parvati Bhujbal, a CPI member, told GX while recalling the strike led by Samant, “The 1982 strike took a heavy toll on our lives, there was no earning member in the family. My husband was busy in party work. I had to be the one taking responsibility of the family. Me and my mother-in-law, we were running the home by selling vegetables. After that strike many mill workers left Mumbai, and the rest took other jobs, some took jobs of watchman, some became street vendors.” Parvati taai had joined the CPI after her marriage in 1981. Her husband, Com. Ashok Bhujbal, was already a party member and worked with Dange himself. She herself worked extensively with Com. Dange’s daughter Rosa, though Parvati’s participation became limited after Dange’s death. During the strike, her husband was arrested on false charges of murder. They had a 6 months old daughter at that time. Ashok Bhujbal was working in the India United Mill in Byculla. He left that job after the strike.

For many Dalit-Bahujan workers, mass closure of the mills meant getting pushed back into the same old economic and social slump. “My grandmother was working in the Dawn Mill at Lower Parel during the British era. She was earning Rs. 40 per month. There was economic mobility for people from lower castes for the first time, as they were getting mill jobs. The mills should have been saved.” said Madan Khale, a former CPI worker who is now active in the BSP. “While we can talk about the ‘glorious strike’ and all, but it is true that the workers got crushed,” said Com. Prakash Reddy of the CPI.

The CPI workers the authors spoke to criticised the prolonging of the strike under Datta Samant, and said Dange’s strategy of “progress and retreat” made more sense. Though there might be differences about the underlying reasons, everyone we spoke to agreed that the Bombay cotton mill industry shouldn’t have shut down. The CPI veteran leaders the authors spoke to, broadly maintained that regardless of how the strike was fought, the mill industry would have shut down in any case due to changes in the nature of global capital where big mills were being increasingly replaced by smaller decentralised units and a once organised work-force was being converted into unorganised contract-based labour. Some erstwhile striking workers were opposed to the CPI supporting Datta Samant in the first place. “He was sent by the Congress only. Supporting him was a mistake. By supporting Datta Samant, you lost the meaning of your symbol as a Communist Party. Now anyone with any symbol could come and ask votes from workers. Our party never recovered after that,” said one of the Kamgar Union workers.

(To be continued…)

Feature image: Abandoned machinery at Madhusudan Mills, Lower Parel. Credit: Wikipedia Commons