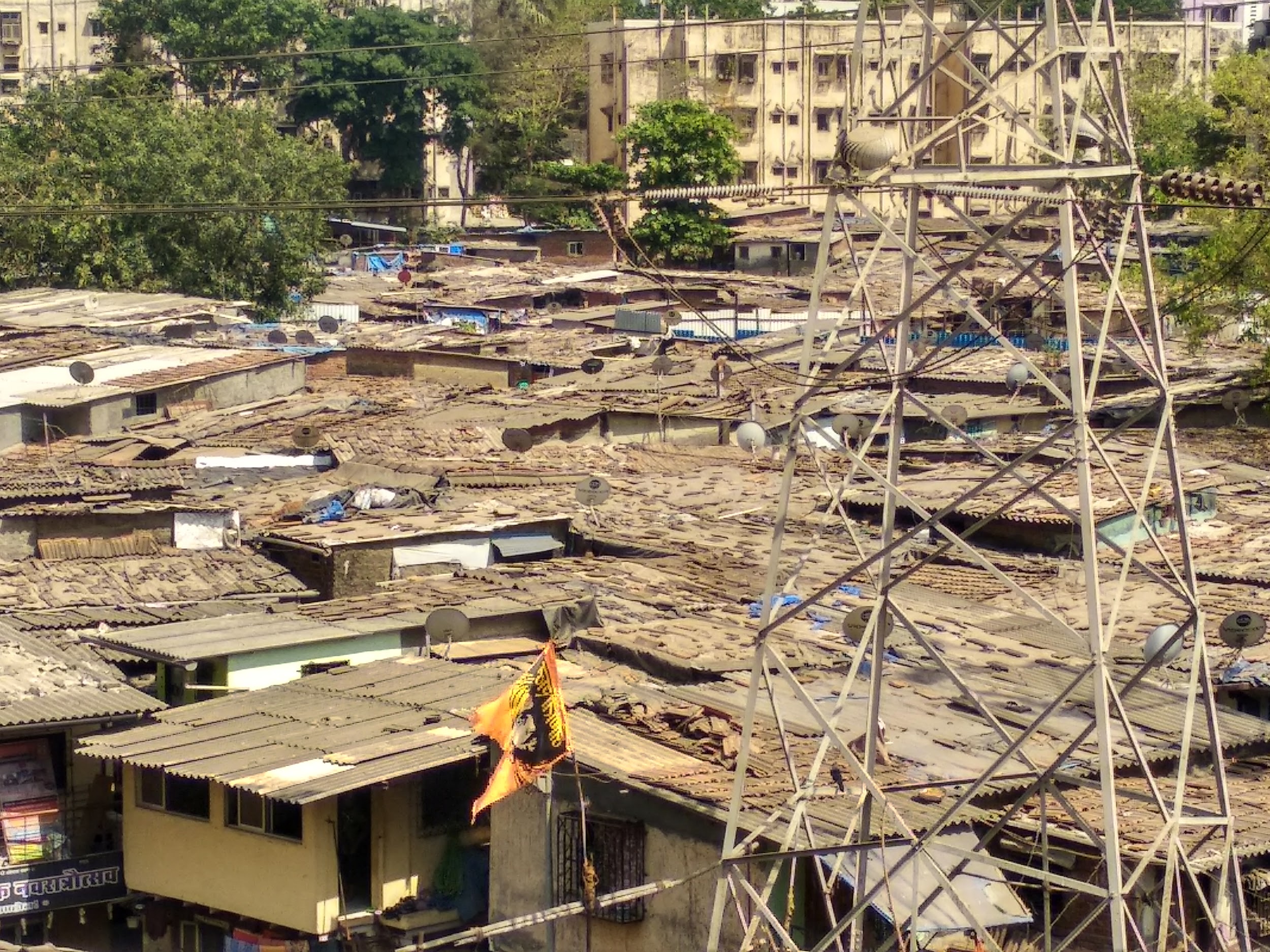

Mumbai – India’s bustling “Financial capital”. Carefully hidden beneath the city’s hustle, bustle and ruthlessness, its money and politics – lies a chilling history of the city’s cotton mill workers and their century-long struggle that once took the city by storm. Episodes One and Two in the series spoke about the history of the Satyashodhaks, Dr. BR Ambedkar and Com. SA Dange’s early attempts at organising Bombay’s mill workers. In this third episode, the authors, Arati Kade and Tathagata Sengupta write about the height of the movement in the 1960s-70s, organised by the historic Girni Kamgar Union, led by one of the most highly spoken about leaders in the history of the struggle – Com. Krishna Desai. This is also the period that saw the rise of the Shiv Sena in the Bombay political turf.

Episode 3 (1960s – 70s): Krishna Desai’s Girni Kamgar Union, the Dalit Panthers, and turbulent times

The struggle of the girni kamgar never did rest, and the decades following the 1947 transfer of power saw repeated mass strikes and militant labour organising.

The 1960s were grave, turbulent times for Bombay, much like other parts of the country and the world at large. These years saw battles, victories and defeats, and have since been oft-remembered for their militant struggles for liberation, their promise of an equal society, and the cruel counterattacks by state and capital leading to where we are today.

Reportedly the only Bhagat Singh statue in Mumbai, erected by Com. Narayan Ghagre of the Girni Kamgar Union. Kalachowki.

Krishna Desai was a militant trade union leader, affiliated to the CPI. In a decade that saw unprecedented upsurge of working class politics, led by the girni kaamgar of the city, Krishna Desai emerged as one of its most prominent leaders, whose militant approach to trade unionism rattled the government and the capitalist class. Desai was not the sort of trade union leader who would restrict himself to strategising and coordinating political actions, he would himself fight on the streets and “do the dirty work”. “He would not let them plant one saffron flag in the entire Lalbaug area. He would personally remove them,” said one of his colleagues to GX.

Desai ran training centres in the chawls of Girangaon where young workers would be trained in militant physical combat including the use of sticks. This training was to prepare workers for fights that would take place against the “gunda unions” floated by the mill owners to undermine the workers’ strikes. “Challenge meetings” would be organised daily – with each side taking up the challenge of organising meetings inside each others’ bastions. Often, such meetings would end up in physical fights aimed at taking control of the mohallas. On various occasions, future Shiv Sena leaders were cornered by enraged workers and physically beaten up. Desai himself was known to have gone after moneylenders who used to lend money to desperate workers’ families at high rates of interest and then harass them in the name of loan recovery. Street by street, chawl by chawl, mill by mill – the girni kaamgaar of Bombay fought against the bourgeois classes and their political apparatus. The Kamgar Union office in Parel acted as the war room. On various counts, the party leadership of the CPI was opposed to Desai’s militant brand of politics. “They knew that as long as Com. Desai was allowed to remain, the bhagwa jhanda [saffron flag] will never find a foothold in Bombay,” said one CPI activist. The Sena had made up its mind to eliminate Desai and the Kamgar Union leadership.

“…the problem of dalits, or scheduled castes and tribes, has become a broad problem, the dalit is no longer merely an untouchable outside the village walls

and the scriptures. He is untouchable, and he is a dalit, but he is also a worker, a landless labourer, a proletarian. And unless we strengthen this growing revolutionary unity of the many with all our efforts, our existence has no future.” – Dalit Panthers’ Manifesto, 1973

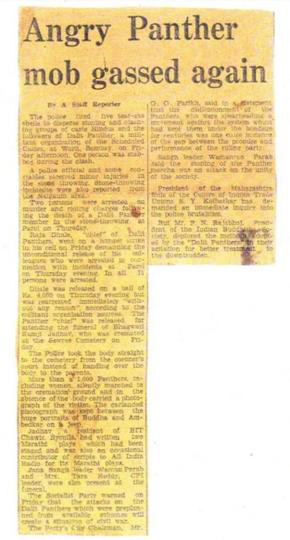

The ‘70s was the decade that saw a new phase of militant dalit struggles, aiming to annihilate caste. The most notable of these forces was perhaps the Dalit Panthers, a movement largely built up by Buddhist and Marxist dalit youth in the state, led by anti-caste leaders like Namdeo Dhasal, Raja Dhale, Bhagwat Jadhav, and others. The Dalit Panthers called out established dalit organisations like the Republican Party of India for getting co-opted by the Congress-led ruling elites, and took the fight for demolishing caste to the streets.

Though Dhasal and several others leading the struggle had shared histories and personal relations with some of the contemporary CPI leaders, and received crucial support in terms of shelter when they were being hounded by the administration, the CPI maintained their distance from the Panthers. In stark contrast with Satyashodhaks’ ideas of centralising questions of caste hierarchy inside working class organising and tying together the struggles for annihilating caste and class hierarchies, the CPI leadership regarded questions of caste as a “distraction” for working class politics. “These questions about caste, religion, etc. are cropping up today in your generation. In those days we knew capitalists are capitalists and workers are workers, we made no distinctions based on caste or religion,” a veteran CPI leader told the authors, when asked about the social composition of Bombay’s then mill-owners. It is telling how even when a militant anti-caste movement such as the Dalit Panthers were sending shivers down the state-capital nexus, the left leadership of the city remained immune to questions of social justice in the context of the mill workers’ struggle.

Source: Hindustan Times

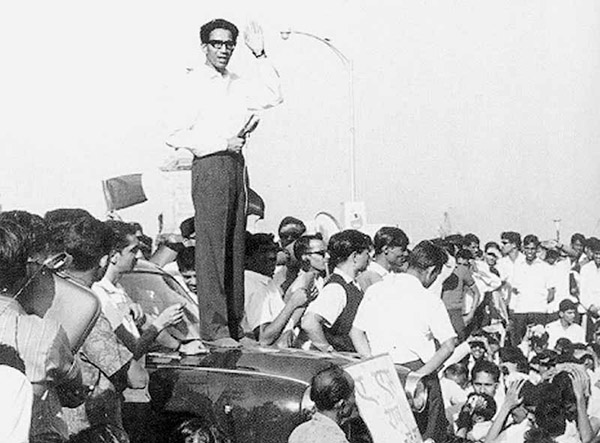

For the state administration and big capital however, both movements were identified as the principal enemies. It was with the aim of countering the dual mass upsurge of working class and anti-caste political movements in the state that CM Vasantrao Naik (Congress) propped up Bal Thackerey and the Shiv Sena as a militant front, in 1966. “I will emasculate the Left,” declared Bal Thackerey in his magazine Marmik. Shiv Sena attacked communist rallies and offices and also broke a number of strikes called by the trade unions.

On 5th June 1970, Shiv Sena assassins stabbed Krishna Desai to death. On a dark rainy evening around 70-80 people armed with knives and sticks stabbed him and one of his associates, Prakash Patkar, in his home at Tawrepara. “We must not miss a single opportunity to massacre communists wherever we find them,” said Bal Thackerey while congratulating Desai’s murderers.

A young Bal Thackerey addressing the public. Source: Internet

Four years later, on 10th January 1974, Dalit Panthers leader Bhagwat Jadhav was stoned to death by Thackerey’s men at a historic Dalit Panthers rally led by Namdev Dhasal, from Dadar to Mantralay.

Several colleagues who had worked alongside Krishna Desai described the events that unfold after his murder. Vast masses of workers took to the streets, and vowed to decimate Thackerey and his party. “We wanted to kill him, and we would have,” said one of them. As Desai’s funeral procession passed Thackerey’s office near Shivaji Park, several agitated workers and leaders like Com. GL Reddy, entered the building and destroyed his office out of the rage.

The CPI party leadership however decided against such actions, and pushed the issue into the courts replacing the political battle by a legal one. Even after the murder of Desai, the party leadership considered the Sena as a “fringe” element and asked the workers to rely on the state administration and legal apparatus for justice. Such laxmanrekhas to working class radicalism drawn by a non-working class leadership broke the moral strength of the struggling workers. Before his death, when Krishna Desai raised concerns about the emergent Bal Thackerey, he was reportedly told by Com. Dange that Balasaheb “dimaag se kam hai, ye sab ladai jhagre marpit se kuch nahi hoga. [The battle with Thackerey is a battle of minds, beating people up isn’t going to lead anywhere.]” Many of the top Communist leaders of Bombay had known Prabodhankar Thackerey and his young son Bala through their Maratha Press during the Samyukt Maharashtra agitation – something that both the Communists and the Thackereys were part of.

The impact of the “emasculation” of the struggle by openly killing its top leader, coupled with reluctance of the party leadership in taking the fight back to the enemy camps, led to alienation of the working class from the CPI leadership, according to many critics of the decision of sticking to legalistic forms of agitation even when the workers themselves were ready for militant retaliation. Though Com. Prakash Reddy of the CPI differs. “The party leadership did not believe that this was a question of targeting individuals who might have orchestrated the killing, and that the response should be mass movement. And I still think that was the correct decision,” he said. Reddy’s father, Com. GL Reddy, was one of the frontline militant leaders of the Kamgar Union and was one of the activists who wanted to destroy Thackerey that day.

Despite public sympathy owing to the assassination, Krishna Desai’s wife Sarojini Desai lost the immediate by-elections which she contested to replace her deceased husband. Wamanrao Mahadik defeated her – though by a thin margin – to become the first Sena MLA of Bombay. The saffron flag was finally planted in the heart of the girni kaamgaar colony of Laalbaug – a bastion of Bombay’s militant left unions till that point of time. This was only the beginnings of subsequent takeover of the city’s working class politics by the Sena for a long time to come.

(To be confined…)