Mumbai – India’s bustling “Financial capital”. Carefully hidden beneath the city’s hustle, bustle and ruthlessness, its money and politics, its cricket, movie and real estate industries, and its never-ending run for financial growth – lies a chilling history of the city’s industrial workers and their century-long struggle that once took the city by storm. The story of Mumbai and its working class movements is a story of the simultaneous rise of Indian capitalism, and its faithful hand-maiden – Hindutva. It is a story of intense political strife that fundamentally changed the city and its politics forever. On the week of the International Workers’ Day, in May, Arati Kade and Tathagata Sengupta spoke to few of Bombay’s textile mill-workers whose fight was a defining episode in the history of the city’s working class politics.

In 5 episodes, the authors recount some of the pitched battles that took place between the city’s textile mill workers and the industrialist class through the 20th century. Battles for every street, every chawl and every mill in the city’s “Girangaon” – the textile mill area comprising of Parel, Byculla, Cotton Green and Worli. Battles that were also against caste society, at least in the initial period. Battles that were won, and battles that were lost.

Bombay’s first textile mill was established in 1854. Though the initial few decades saw slow growth in the industry owing to the mass produced Manchester mill cotton, it picked up steam towards the end of the century. Two key factors behind the spurt was increasing supply of cheap American cotton produced from slave labour that brought down the global price of cotton including that produced by the Maharashtra farmers; and the devastating famine of 1877-78 that pushed lakhs out of agricultural and into the city as footloose labour. As many as 6 lakh people are estimated to have died across the country in this famine. Accounts from those early mill days in Bombay talk of hundreds of destitute famine-stricken workers queuing up for work at the mill gates every morning. While some would be hired, the rest would linger around the factory premises for weeks in the hope of recruitment. There were no fixed working hours, the workers were not even allowed lunch breaks. There were no holidays in the week, no age restrictions when it came to hiring children, no workplace safety and no protection for the large number of women workers. According to the 1881 Census, 23 percent of the labour force consisted of women and 22.76 per cent of children below 15 years. In absence of electricity mills functioned from sunrise to sunset, with working hours varying from 10-12 hours in winter to about 13-14 hours in the summer.

The cheap cost of production at Indian mills subsidised by abundant cheap labour, threatened the profits of the British mills, who had to allocate budget for workers’ protections. British manufacturers therefore mounted pressure on the Indian colonial administration to impose labour laws in the Bombay mills that would ensure stipulated spending or protection of children and women workers, restrict working hours, and put lower limits on the hiring age. The Bombay mill owners organised in order to resist the mounting pressures. The Bombay Mill Owners’ Association was formed. But eventually, through several Government Commissions, the Factories Act was drafted, guaranteeing some basic safeguards for the first industrial workers of this country.

This would be the beginnings of the textile workers’ struggle in Bombay.

Episode 1 (The 1880s): Satyashodhaks and the Textile mill-worker

The task of organising textile mill workers in the city began as early as the late 1800s, when anti-caste social reformer Jotiba Phule and the Satyashodhaks – the social reform movement founded by him – began conducting speeches and meetings with thousands of mill-workers who had migrated to the city from rural Maharashtra in search of work. Narayan Meghaji Lokhande, Phule’s colleague and one of the Satyasodhaks, established the “Bombay Mill Hands Association” in 1884 – one of the first workers organisations in the country, and the first for the Bombay textile mill-workers. Before joining the Satyashodhak Samaj, Lokhande was working as a storekeeper in a textile mill, which is where he observed the problems faced by workers.

In the first ever meeting of industrial workers in Bombay’s history that took place in Parel on 23rd September 1884, the Mill Hands Association brought out the following charter of demands:

- One complete day of rest every Sunday for all mill-hands.

- Half an hour rest at noon on every working day.

- Hours of work from 6:30 am to sunset.

- Payment of wages be made not later than 15th of the next month.

- A workman sustaining serious injury in the course of work at the mill, disabling him for sometime, should receive full wages until he recovers, and in case of being maimed for life, suitable provisions be made for his livelihood.

The Satyashodhaks were led by the likes of Phule, Lokhande, Krishnarao Bhalekar and others. Many of them belonged to phulmaali families, working in the urban flower markets of cities like Pune and Bombay. Some of them were the first from their families to enroll in formal education, thanks to schools run by Christian missionaries. Although the colonial formal education system did not officially make an exception based on caste, the upper caste teachers who taught in these schools were all Brahmans who found various ways to block “Shudras” and “Atishudras” from entering these schools. Missionary schools provided therefore the only opportunities for a formal education for all such communities. It was at these missionary schools that students like Jotiba got exposed to European Enlightenment ideas and scholars like Thomas Paine, and decided to launch a lifelong battle against the Hindu caste system.

The Satyashodhaks took on the battle against existing structures of social and economic oppression on various fronts, forging various solidarities. They set up schools for those who had been thus far denied access to education, organised workers and agricultural labourers, fought against poverty, fought against communal riots [one of the first organised communal riots in Bombay took place in 1893], lobbied with the Government for laws guaranteeing better working conditions, fought for women’s rights across castes. Lokhande urged members of the barbers community to boycott the tonsuring of Brahman widows, as part of the ongoing struggle for widow remarriage. The Satyashodhaks brought out their own journals and magazines. Deenabandhu, official organ of the Satyashodhaks, was one of the first magazines to take up the fight for social justice and labour rights, and soon became widely influential. The magazine took on crucial fights with Kesari – the leading Marathi newspaper of the time, edited by Bal Gangadhar Tilak. Tilak faced bitter criticisms from the Satyashodhaks for his openly casteist views, and the Deenabandhu played a crucial role in this.

Phule and Lokhande played instrumental roles in introducing provisions for workers’ rights in the newly drafted Factories Act that was passed in 1891. Lokhande was himself a member of the Lethbridge Commission set up for this purpose. The Bombay Mill Hands Association led mass agitations on their demands, and conducted meetings that would be attended by tens of thousands of girni kaamgars.

Pressure from these agitations forced the Mill Owners’ Association to accept the right to a weekly holiday on June 10, 1890 – the first victory of the labour movement in Bombay’s history. “The title of Mahatma was conferred onto Jotiba not by the elite, like in the case of Gandhi, but by the Girni kaamgars of Bombay”, said an old mill worker from Kalachowki.

The Satyashodhak movement gradually phased out, after the death of Shahu Maharaj. The Satyadhodhaks’ movement was the beginnings of a long battle ahead, and some of today’s organisers do point out that their scale of organising was possibly not comparable with what was to happen in the next century, but one has to recall that these were also the initial years of formation of the industrial working class itself. Bombay’s mill-workers’ struggle would however reach different proportions early in the next century.

(To be continued…)

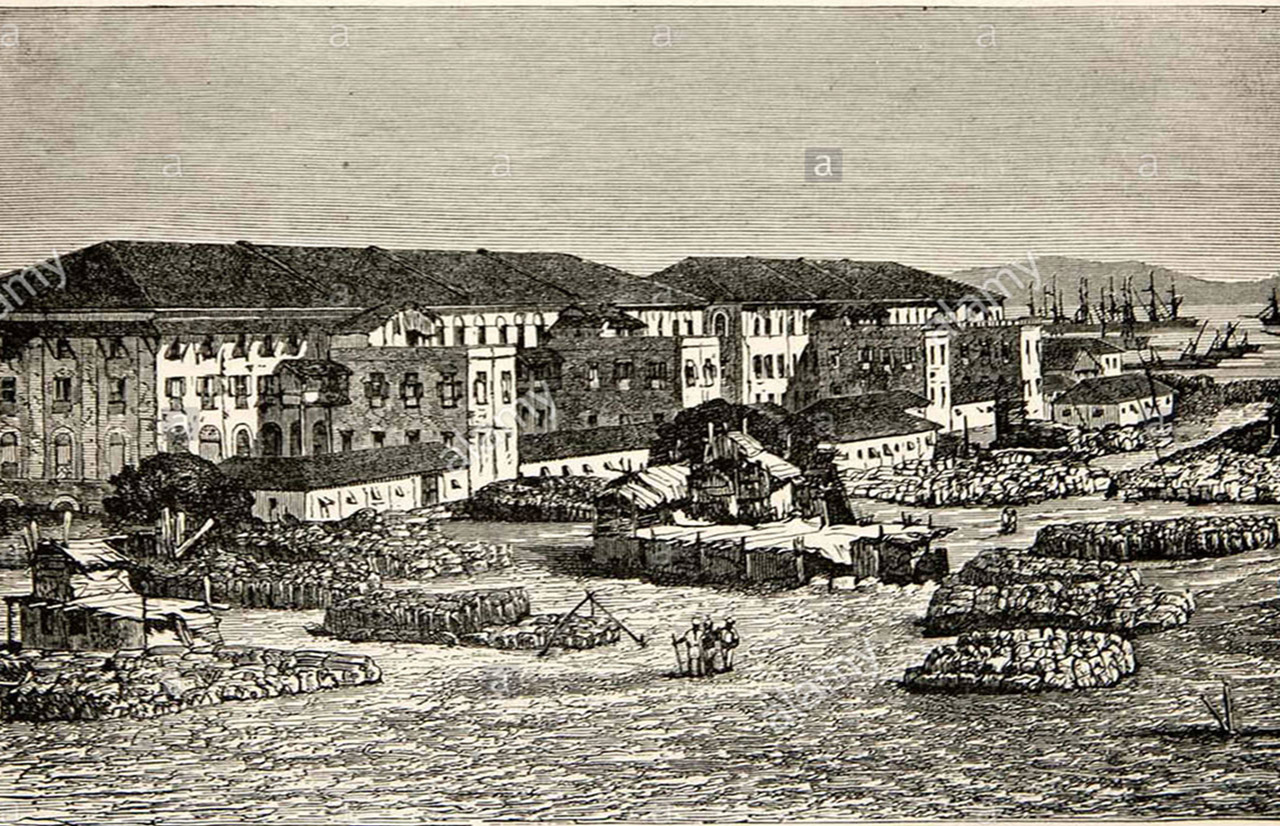

Cover Image : Cotton Market at Bombay