Dozens of Mumbai-based groups condemned and protested the “clean chit” given to CJI Ranjan Gogoi in the sexual harassment scandal that has rocked the judiciary. A GroundXero report.

Complaint and Proceedings

An affidavit submitted on April 19 by a former employee of the Supreme Court (SC) alleged that the sitting Chief Justice of India (CJI) Ranjan Gogoi had made wildly inappropriate and unwelcome sexual advances towards her. At the time, the complainant was employed as a junior court assistant (JCA) in Justice Gogoi’s residence office.

The alleged incidents of harassment took place last October, after which she was transferred thrice. In November, a disciplinary enquiry was initiated against her, alleging that she displayed “reluctance and questioned the decision of senior officers,” that she attempted to “bring influence” from “unacceptable quarters” regarding her transfers, and finally that she “unauthorizedly absented herself from duty” on November 17 and showed “insubordination, indiscipline and lack of devotion to duty”. The disciplinary committee did not allow her a defense assistant, conducted the proceedings ex parte, and dismissed her from service in December.

She and her family have been allegedly hounded and harassed since then. To quote The Wire, and based on the complainant’s affidavit,

First, her husband and one of her brothers-in-law – both employed with the Delhi police – were suspended on allegedly frivolous grounds.

Next, another brother-in-law who was appointed as a junior court attendant through the CJI’s discretionary quota on October 10, 2018 – a week after Gogoi became the CJI – was also dismissed from service without reason.

Finally, she herself was arrested in a case of bribery that was registered in March 2019 – almost three months after her dismissal from the Supreme Court.

Justice Gogoi refuted the allegations, called an extraordinary hearing soon after the news broke and headed a three-judge bench that discussed the allegations made against him, all the while alleging that there was a larger “conspiracy” at play. This has been roundly criticized. Soon after, it was decided that a three-member committee of sitting SC judges would look into the sexual harassment allegations. The complainant testified before the committee on 26 and 29 April.

The complainant subsequently decided against participating in the internal inquiry. Her reasons were: she was not allowed to have her lawyer present in the room while testifying, that the proceedings weren’t recorded (video or audio), that she had not been provided with copies of the testimony, and finally that the procedures to be followed by the committee were not communicated to her. In a press release, she emphasized that the committee didn’t seem to appreciate that “this was not an ordinary complaint but was a complaint of sexual harassment against a sitting CJI”. In a wonderful article, Gautam Bhatia argued that

It hardly needs to be said that this is not an essay about innocence or guilt, but rather, about the preconditions necessary to ensure that questions of innocence or guilt can be answered adequately. And for that, this is the point: at the time of writing, the sexual harassment complaint against the Chief Justice has been handled by no fewer than nine judges of the Supreme Court. As the above analysis demonstrates, each one of them has acted in ways that perpetuate the existing power imbalance… [The judges] have shown themselves unequipped to address – or even acknowledge – the bleeding heart of the problem: that this is a question of power, and without addressing that, you address nothing.

Despite alleged reservations within the SC, the committee decided that it would continue its proceedings ex parte. Disappointingly (and perhaps unsurprisingly) the committee found “no substance” in the allegations of sexual harassment against the CJI. The committee has said that its report was not “liable to be made public,” a claim that has been contested by the complainant, who recently spoke to members of the press about her ordeal.

Adv. Rajeev Dhavan has highlighted the extent to which the procedures followed by the in-house committee were seriously flawed. The SC’s credibility has been questioned, both in the press and on the streets, where protests erupted soon after Justice Gogoi was given a “clean chit” by the in-house committee. Several protesters were detained as well.

The Court’s Credibility

The inability of the SC to effectively and fairly investigate a serious and credible allegation of sexual harassment has raised questions of its credibility. Many commentators have rightly pointed out that it is plainly the case that the CJI’s actions violate fundamental principles of natural justice; more seriously, his actions are in direct contravention of the Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace Act (2013). An open letter by a group of women lawyers and activists states

…the CJI not only declared the allegations false but further stated that these allegations threaten the independence of the judiciary. He also declared that the complainant had a criminal background. The bench further asked the media to show restraint to protect the independence of the judiciary. None of these observations were based upon any investigation by any competent authority.

The Women in Criminal Law Association (WCLA) has similarly raised a number of important questions. How did the in house committee conclude post haste that the allegations have no substance without deposing the various individuals involved in the complainant’s alleged victimization? Why was the complainant denied legal assistance, a constitutionally protected right? Why did the in-house committee proceed with the investigations ex parte despite being cautioned by Justice Chandrachud in a letter addressed to them, that was reportedly written after consulting with seventeen sitting SC judges? And perhaps most importantly, what legal recourse can the complainant rely upon to question the legitimacy of the in-house committee’s proceedings, short of approaching the SC which has already failed her? The apparent lack of viable options to seek legal recourse precipitated the protests outside the SC. To quote the WCLA statement:

Viewed thus, the detention of protesters today forms part of a consistent trend: of use of State power to persecute and isolate the complainant from any support, and shield the Supreme Court from accountability.

A number of groups have released press statements condemning the sham inquiry into the allegations against the CJI, including Women Against Sexual Violence and State Repression (WSS), the People’s Union for Democratic Rights (PUDR), and the People’s Union for Civil Liberties (PUCL).

As this story unfolded, Indira Jaising, Anand Grover, and their NGO Lawyers Collective (who have taken up the issue of procedure followed by the SC in response to the sexual harassment allegations against the CJI) have been served notice by the SC for the alleged “mis-utilisation” of foreign funding under the Foreign Contribution Regulation Act (2010). The notice itself was issued in response to a petition by “Lawyers Voice,” which asked that there be an SIT probe into the Government’s inaction against the Lawyers Collective “for offences under the Indian Penal Code, Prevention of Money Laundering Act, Prevention of Corruption Act and the Income Tax Act.” Activists and civil society have rallied in support of Jaising and Grover, pointing out that the actions of the SC (in particular CJI Gogoi) amount to victimization, and have questioned the urgency with which the Lawyers Voice petition was processed.

Protests

Protests against the “clean chit” given by the in-house committee to Justice Gogoi erupted soon after the news broke, and the protesters outside the SC were summarily detained. Similar protests took place in the following days in Bengaluru and Hyderabad.

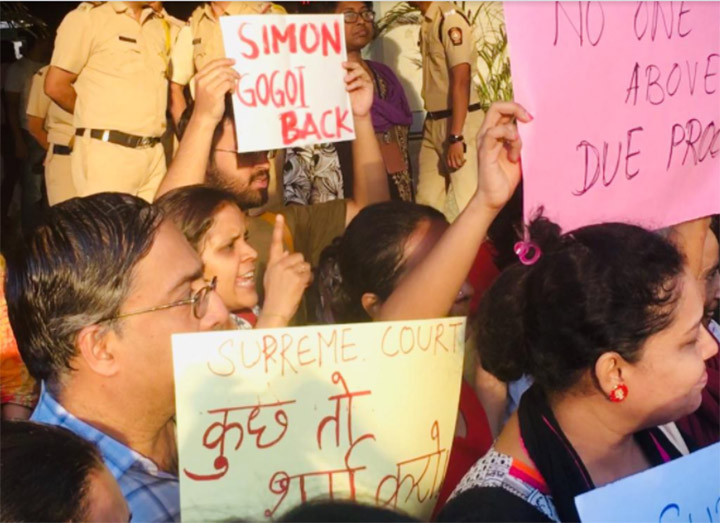

GX witnessed a fifty-strong group of activists, lawyers, and students (mostly women, although there were a few men) assemble in Mumbai on 9 May at around 6PM. Protesters pressed into service the hood of a police jeep, on which sheets of chart paper were laid out and slogans like Supreme Injustice, Kanoon Ke Aage Sab Barabar [All Are Equal Before The Law], and No Justice In Sealed Envelope.

Positioning themselves, posters in hand, on the steps that lead up to the platforms at Dadar East Station, the protestors launched into passion-fueled chants decrying the clean chit (Clean Chit Nahi Chalega!) and imploring the SC to come to its senses (Supreme Court, Hosh Mein Aao!).

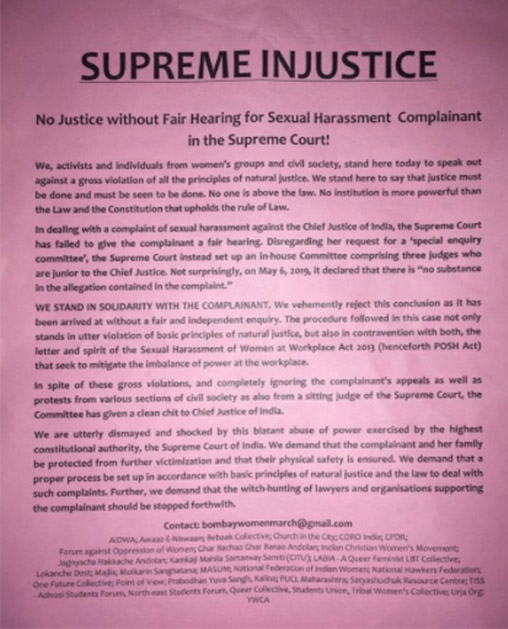

As the chants continued, the representatives of around thirty organizations behind the organization of the protest busied themselves pamphleteering. Many of the passers-by that had stopped to take in the protest that GX spoke to knew of the allegations against the CJI, but were not aware of the extent to which the episode represented a miscarriage of justice.

When clued into the details, their response was overwhelmingly in support of the complainant: “Jo Supreme Court main ho raha hai, woh theek nahin hai [What is happening in the Supreme Court, isn’t right],” said one young woman.

Unlike the protests in Delhi and Bengaluru, the protests in Mumbai were not broken up by the police. GX will continue to report on further developments in Mumbai as this story unfolds; for now, we leave the readers with some scenes from the protests.

Something is rotten in the street of Denmark! Supreme court may have its power and discretion to do anything and act to their wish.But, the people’s voice and concern can not be ignored.Come in the open and expose the truth!