One of the main peoples to be directly impacted by the fallout of Mumbai’s Coastal Road Project are the Koli fishing communities in the city. These people have sustained themselves on daily small-scale fishing off the city’s coast for centuries, and are amongst the first makers of today’s sprawling metropolis. They had however no prior information about the Rs. 15,000-crore project that is going to displace them from their lives and livelihood. As Maharashtra went through its third phase of polling today, and looks ahead to its fourth and final phase that includes Mumbai on April 29, the fishworkers are calling for a boycott of the vote. A GroundXero report. In a follow-up report we will discuss the latest interim court order temporarily stalling the construction work, how the order is being undermined, the longer history of this fight, and why the fishworkers are demanding complete scrapping of the project.

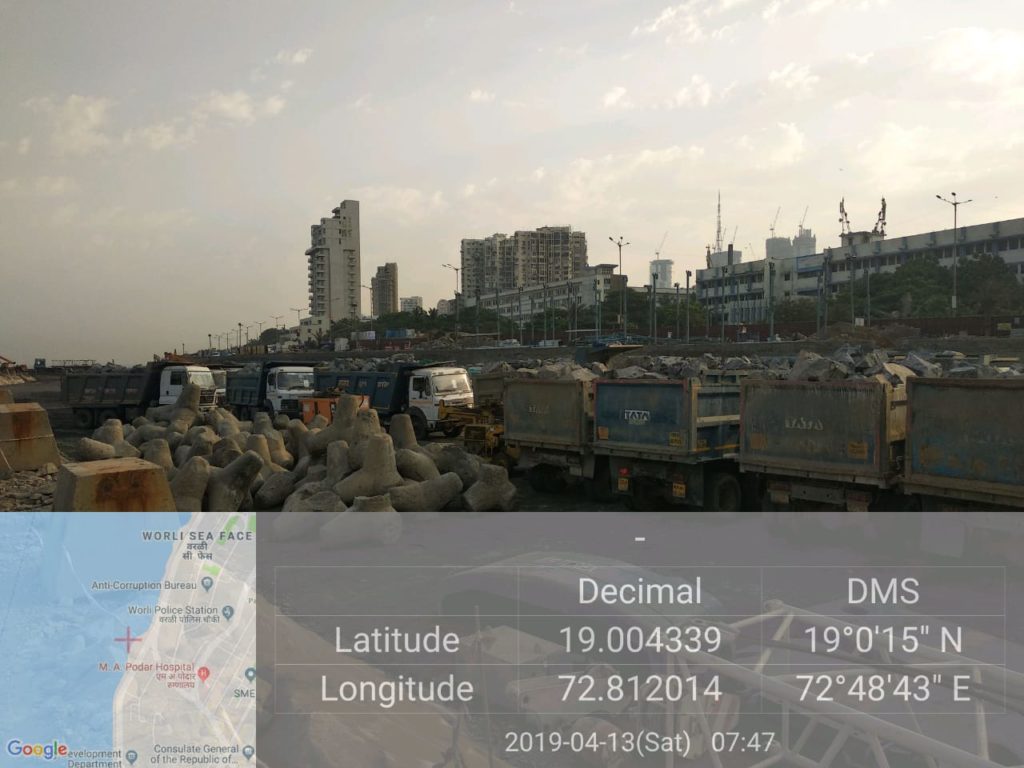

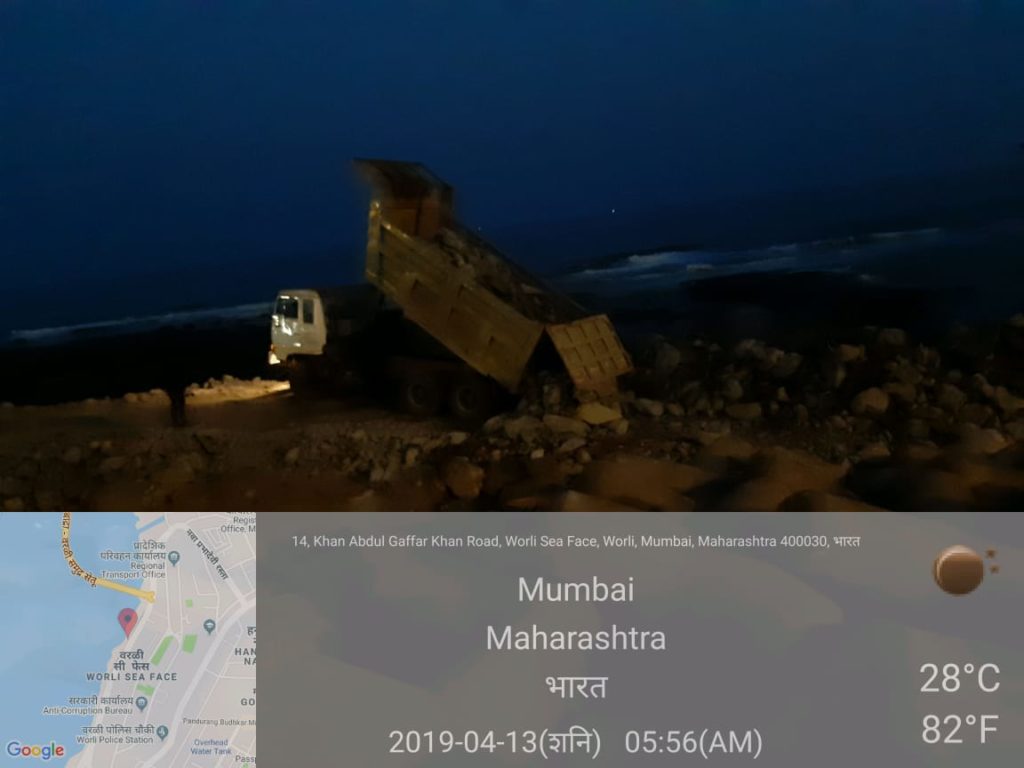

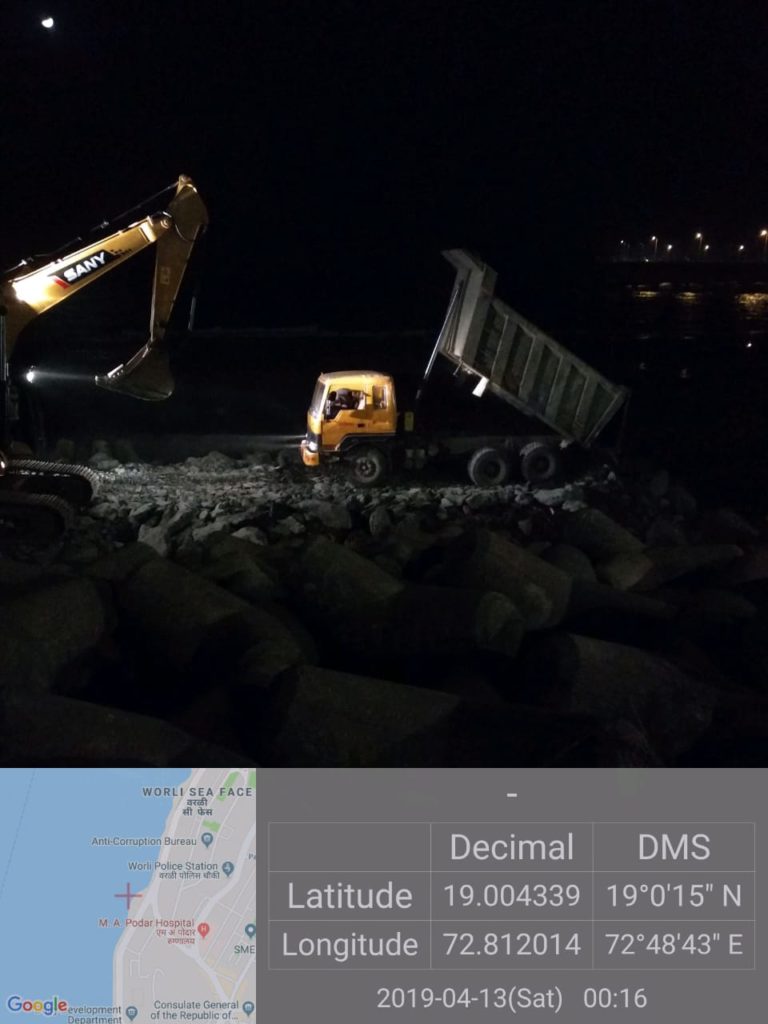

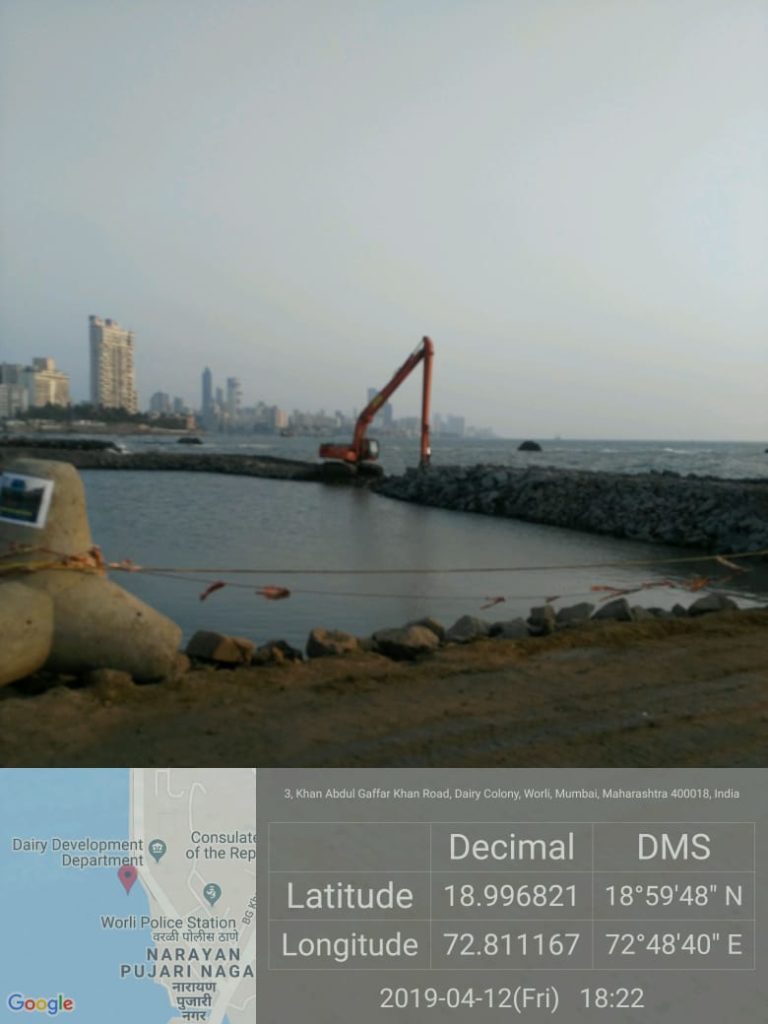

Stretching from Marine Lines in the south to Kandivali in the north, the Coastal Road Project – an 8-lane highway cutting across the sea – was approved by the Ministry of Environment, Forest and Climate Change (MoEF) in 2015, despite severe objections and protests by the local fishing communities and environmental activists. The Coastal Road, which is supposed to be a mix of tunnels, sea-links, underpasses and reclaimed roads, would be reserved only for private 4-wheelers. The Shiv Sena, presently in control of the BMC, have claimed that the road, once in operation, would take vehicles from Kandivali to Nariman Point – a distance of 34 kms – in 15 minutes. Last October the BMC handed tenders for the construction of the project to companies such as the L&T, Hindustan Construction Company (HCC), etc. Soon after, in the name of “surveying the area”, the BMC started the process of filling up a 10km-long stretch of the sea, from the Worli Sea Link to Priyadarshini Park, with boulders and mud. Extensive work was begun, dumping debris, pulverizing rock surfaces with machines and building stone bunds in the sea.

The local fishing families had moved the High Court against the project, asking for it to be scrapped. They allege that the project, approved illegally without conducting the due process, is going to destroy not just the marine ecosystem in the region, but also the lives and livelihoods of those who survive on small scale fishing off the coast. Last Tuesday, the Bombay High Court put an interim stay order on the construction of the road by the BMC. But the project itself is yet to be scrapped.

“Coastal Regulation Zones” and the attack on our coasts

The western coast of Mumbai is known for its ecological diversity. There are at least 12 fishing villages along the coast that depend on the coastal ecosystem for their livelihood. They use the beaches to park their boats, sort and dry fish, and repair their nets and vessels. Such common areas belonged to these communities for centuries, before the so-called “Coastal Regulation Zones” were introduced in 1991 as the country’s economy prepared itself for the world market. The “Coastal Regulation Zone (CRZ) Notification, 2011” was supposed to “regulate land-use” and construction activities in coastal areas while “protect[ing] the lives and livelihood of the fishing communities”. With time, however, these communities came to be looked upon by the State-Corporate nexus as “encroachers”, and questions of “protecting them” were soon transformed into those of “protecting the coast from them” by taking away their access to these spaces.

Environmental activists have for long argued that the rich eco-diversity of the coastline dense with natural features such as rocky headlands, bays with sandy beaches, estuaries, mudflats and more – are essential for sustaining the diversity of habitats that form this fragile coastal ecosystem. However, for the administration, these are mere “sharp kinks in the coastline that must be replaced through reclamation into gentle curves to smoothen traffic flow.” Instead of taking measures to protect the vulnerable ecosystem, the Union Government in fact further hollowed out the already compromised CRZ Notification, through an amendment last March that removed the clause requiring prior environmental clearance for construction projects. “Prior approval” was replaced by “regulation” of violation after the construction activities actually take place. Through such legislative stabs and other linguistic trickeries such as renaming “shorelines” as “bays”, “No Development Zones” as “Potentially Developable Zones”, reclamation of open spaces as “Green Reclamations”, etc., huge amounts of coastal lands around Mumbai have been successively brought under development projects over the years. In a highly space-starved city surrounded by water, this is akin to opening up of an entire new playing field for Mumbai’s immensely powerful real estate and builder lobbies.

In 2015, despite opposition from environmentalists and local fishing populations, the Environment Ministry cleared the Coastal Road Project, which was expected to “reclaim” 168 hectares of land from the sea and 27 hectares of mangrove land. No public hearings were conducted. A so-called ‘Conditional NoC’ submitted by the Welfare Society was shown as NoC for the project, “from residents of Worli Gaao”. This Welfare Society was registered only recently, and has been alleged to have links with the builders’ lobbies. Although the Society reportedly has some members from the Koli community, these members have little connection with the fishworkers. The “Social Impact Assessment (SIA)” for the project, written by a private firm, did not even consult the fisher community. The fishing families are mostly affiliated to a couple of other organisations – the Worli Koliwada Naaka Matsyavyavsay Sahakari Society and the Worli Koli Sarvoday Sahkari Society, both of which have gone to Court demanding scrapping of the project.

It is worth mentioning that through another such modification to the CRZ, the restriction on construction in so-called “CRZ IV areas” was relaxed to allow the building of memorials or monuments of “national importance” and related commercial uses. Within a week of notifying the amendment, the gigantic Shivaji statue, estimated to cost Rs 2,500 crore, and to be located off Mumbai’s western coast, was cleared by the Ministry. “The 190-meter-high statue would reclaim 16 hectares of relatively shallow waters with submerged rock and coral – typically a breeding ground for a range of aquatic fauna,” wrote urban activists Shweta Wagh and Hussain Indorewala in The Wire.

A recent report titled ‘Social Ecology of the Shallow Seas – A report on the impact of coastal reclamation on artisan fishing in the Worli Fishing Zone,’ released by the Collective for Spatial Alternatives, analyses the irreversible damage to the coastal ecosystem, and the terrible impact of the Coastal Road Project on the fishing communities . In its recent order, the High Court said, “The amendment [to the CRZ notification] cannot be read as a free charter for the destruction of the coastal areas. It is urged that the construction of the road in the Coastal Regulation Zone by reclamation, shall be only in exceptional cases.”

Fear of floods in the upcoming monsoons

With the coast being gradually sealed off with concrete, not just the coastal parts alone, the entire city of Mumbai is being brought under the threat of devastating floods. The city has been experiencing regular floods during monsoons – the biggest one in recent history being in 2006. With the coast getting sealed off, the natural run off of the torrential monsoon showers that are to set in within the next 2 months, will be blocked from reaching the sea. “If they are allowed to fill up the coast like this, you just wait for 2 months and watch what happens to the city during the monsoons,” said one fishworker. “The last Tsunami took place in Mumbai 102 years back. There is no chance of another happening anytime soon,” said a BMC official allegedly, when the Koliwada residents brought up the issue of impending flooding of Mumbai.

Already, the Worli Koliwada itself has been regularly getting submerged during rains and high tides. Although the administration has set up a water pumping station right next to the fishing jetty, the fishermen alleged that it is not completed and does not even function properly, and releases or pumps water in a completely unplanned unscientific manner. In effect, faulty functioning of the pumping station has led to logging of water and trash, forming large breeding grounds for mosquitoes.

The Kolis’ own city?

Koli fishing communities are one of the earliest known inhabitants of Mumbai. The ancestors of today’s protesting fisherpeople were fishing in the seas around Mumbai from even before the British came to India. Even the name of the city – Mumbai – is after a Koli deity, Mumba Devi. The imminent displacement of these fishermen and women because of the Coastal Road Plan is however the most recent example of how the city has been snatched away, piece by piece, from some of its makers by the modern financial elite.

The coastal road is meant for the city’s business elite, who want super-fast connectivity within the financial capital of the country, to respond to their ever-growing business ambitions. The Coastal Road, argued by the Government to be the “only solution” to the city’s commuting problems, is to be restricted only to motorists. The Government claims that the road will carry an average of 120,000 cars every day by 2019 from one end of the city to another, easing the city traffic. The estimated cost of 15000 crores is expected to rise further with time. The actual cost of the Bandra Worli Sea-link, for instance, had overshot initial estimates by 430%, while carrying only about 40% of the traffic that was projected.

The key justification for such new projects has been the ever growing number of private vehicles in the city – something that is seen by the current economic paradigm as signs of progress that must be sustained even if at the cost of the survival of working people and the environment. While over the past five years, the population of Mumbai has grown at a steady rate of 0.5% per year, private cars have increased at the rate of 6.4%. By 2043, the current 139 cars per 1,000 persons is projected to swell to about 243 cars per 1,000. “They keep saying we need wider and faster roads. How many roads will you build at this rate when every rich family is having 3 to 4 cars – one for each family member? Why can’t the Government instead of destroying our lives for its wide roads, put a limit on the maximum number of vehicles each family can own?” asked one of the protesting fishermen. Only 7% of Mumbai’s population is estimated to be using motorized transport.

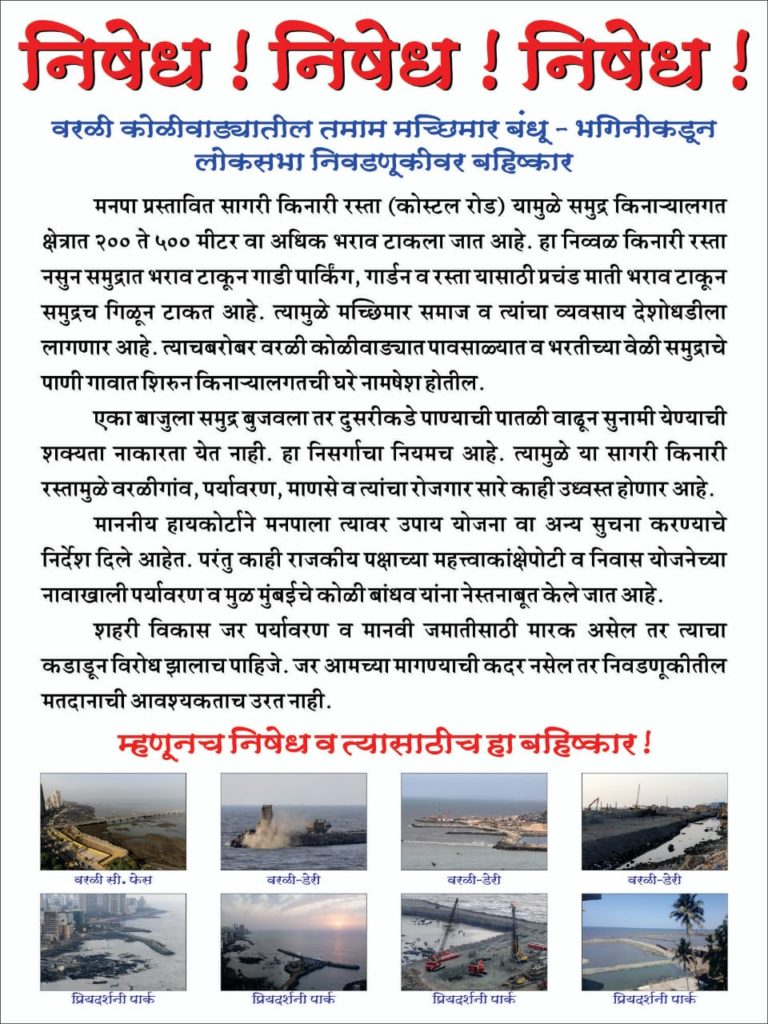

Worli Koliwada Calls for Boycott of the General Elections

The Coastal Road project has become a glaring example of the city’s inequality-driven urban infrastructure development plans. On the one hand when buses occupy only 6% of the total road space in Mumbai today, while moving about 45% of its users, private vehicles – including 2- and 4-wheelers – take up 87% of the road space to move the same number of people. However, while about 170,000 cars have been added to the city in the past 5 years, the number of public buses run by the BEST undertaking have increased only by 108, or at the rate of 0.6% per year. The gutting of the BEST bus transport system and replacing public transport with highways reserved for private vehicles was one of the main reasons why the BEST workers in Mumbai had gone on a historic strike earlier this year.

“Only during elections, all these party leaders come and tell us that Mumbai is ours, that we are the original inhabitants of the city. On other days we are treated purely with contempt and deceit. The fishing communities of Mumbai will teach BJP-Shiv Sena a lesson in these elections,” said one of the Worli fishermen to GX. The Koli community of Mumbai, who have rarely been represented in the state Legislative Assembly historically, have this time decided to boycott the elections. They declared this in a recent notice, and have urged other such toiling communities to do the same.