Three cultural events, the figure of the “people,” and the Kolkata winter. In this second of a two-part article, Abhishek Bhattacharyya writes about a film collective, their annual festival, and other activities in town. The first part of the article, on a little magazine fair and a literary festival, can be read here.

In the first part of this article I’d discussed a little magazine festival and the People’s Literary Festival, and in this one I turn to the People’s Film Festival – to report on a number of events this winter in Kolkata, that mobilised and laid claim to a figure of the people. Weaving a report of the festival with brief reviews of some movies screened there, and quickly contextualising them within both the People’s Film Collective’s overall project, and their location within a politics of the people in Kolkata, I look at how alternative cultural formations are often thriving here, albeit with limitations. To what extent and how might such alternative spaces be ritualistic? What can be the power of such ritual performances? And where might they be exceeding familiar bounds? These are some questions I carry over from the earlier piece.

The People’s Film Festival (17 – 20 January)

One way in which the People’s Film Collective (starting in 2013) has aimed to take forward projects towards building alternatives has been to screen movies in different districts, along with a person who does live translation with a mike, as films are projected on all kinds of makeshift surfaces. Moreover, marking an innovation within the history of leftist education practices in the region, their project of “Little Cinema” has been showing films to kids in schools and various other locations – from Kolkata’s slums to other places around the state. (Bangla readers may wish to look at Paroma Sengupta’s delightful essay on her interactions with kids while participating in and being part of organising these screenings, in the latest issue of Protirodher Cinema). Also driven by a young and gender diverse collective, their projects have evolved into several activities – from making films, to producing long pamphlets/short books on political questions as the “People’s Study Circle”, to publishing 500-800 copies of an annual little magazine (Protirodher Cinema), to curating/editing a collection of essays in English on “People’s Cinema” in India, to generating social media texts as “People’s Media” content for fighting Hindutva propaganda. Their film festival in Kolkata therefore – though itself primarily addressing middle-class Kolkata audiences – is part of a broader project of politics within the domain of culture. For reasons similar to that of the People’s Literary Festival, the film festival too was exciting for telling stories from across the country to Kolkata audiences. Stretching over four days from morning to night, the festival included a wide variety of films – 41 from across the subcontinent, 30 of them documentaries. For curious readers: the festival brochure has short introductions to all the films, PFC members published bulletins after screenings every day (1, 1, 2, 2, 3, 3, 4), and they produced a video with some of the visiting directors.

Documentary films are notoriously difficult to acquire and see, unless one is part of political, academic, film or other such circuits of knowledge/friendships. There are almost no movie halls that screen them, producers have budgets too low for wide publicity, and they at best tend to find some limited viewing at film festivals attended by cine enthusiasts. In such a context the festival curated by PFC is quite a unique event for showing new work from across the country, while being focussed primarily on documentaries. The post movie interactions with film-makers are also often educational through their discussions of film-making process, influences, artistic decisions, funding and more. With their 6th edition this year, PFC organisers have also significantly improved in their ability to host such discussions – for instance, they have reined in a temptation they seemed to have to ruin movies by talking of their endings while introducing them.

The thirst for such a space can perhaps also be gauged from the fact that over 1600 films were submitted for consideration this year, as one of the organisers, Kasturi Basu, said during her introductory remarks. Afterwards, as I discussed this piece with her, she wrote about “the monthly screenings and other mini film festivals PFC organises, because it is primarily on the strength and regularity of these that the work of building a new audience has happened over the years. Doing a yearly event means little actually on its own, so for us, the monthly screenings, little cinema, travelling cinema and little cinema has done the hard work of creating an audience hungry for documentary….When we started in 2014 the festival footfall would be 500….Now it’s 2000.”

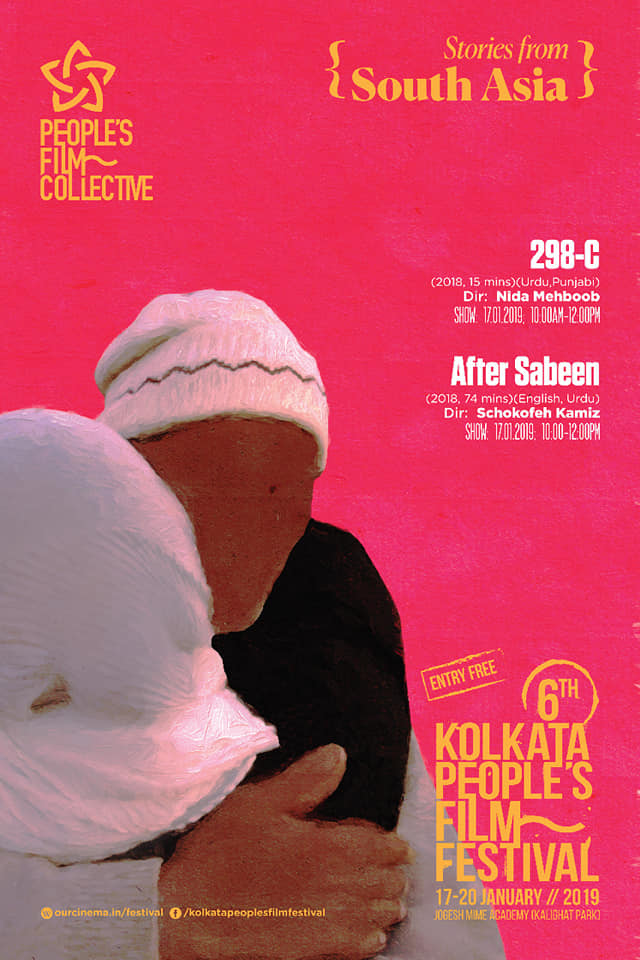

A People’s Film Collective poster advertising two documentaries from Pakistan being screened at the festival.

I missed out on seeing a number of films I’d hoped to watch, especially the films from Pakistan, then Randeep Singh’s Landless about dalit agricultural workers in Indian Punjab, and more. I still did get the chance to see a wide variety of films, the high point being the buzz generating creative telling of workers’ dreams in Old Delhi in Ghode ko jalebi khilane le jaa riya hoon (Taking the horse to eat jalebis) by Anamika Haksar. As the opening text of the film put it: “This film is culled from interviews and dreams of pickpockets, street vendors, small scale factory workers, daily wage labourers, domestic workers, loaders, rickshaw pullers and many others labouring in the city of Shahjanabad, Old Delhi.” Interacting with the audience, veteran theatre practitioner Anamika Haksar spoke of her debut feature film at the age of 59, which took seven years in the making – beginning with the research for it. In different interviews she has spoken about how she received no funding for the movie, and had to use money from the sale of a house, and borrow from friends and family, to make it. And such a beautiful film was born from this painful process. Without seeing it, it is difficult to imagine how animation can be used alongside on-site shooting to string a film about dreams!

At this point, as I was working on a second draft in late February, it started pouring here in Kolkata. The TV that was blaring war mongering “news” in the next room had been turned off. The weather was suddenly cool, very beautiful from my study window, or attached balcony. I stood there and looked at the construction workers scrambling to cover the half-built wall they’ve been working on in the plot of land up ahead, and finding shelter in another under construction building. The pavement dwelling family opposite my building – over one of whose arms a lorry ran over as he was sleeping there couple of years back – rushed about similarly. I looked at the scene, and returned to write about workers’ dreams. In a way (though obviously with various differences), this could work as an analogy for the makers of the film who are from relatively privileged backgrounds, narrating desires of poor workers in Old Delhi, and it could also work as an analogy for its screening in front of a primarily middle-class audience here. Such moments of interaction can be valuable precisely insofar as they may contribute to overturning these paradigms, these hierarchies of access. Projects such as PFC’s are vital in trying to do so by both engaging audiences of relative privilege, while travelling to various other people.

The festival featured a lot of other work that has been less talked of. For instance, among the different films by graduates from the Film and Television Institute of India, Pune, was Maheen Mirza (as director and cinematographer) and Rinchin’s (as assistant director) Agar Wo Desh Banati (If She Built a Country). Both of them also worked together as part of the Bhopal based Ektara Collective, where they participated in making the utterly brilliant and moving Turup (Chess) – which was screened at last year’s festival – through collaborative grassroots level direction processes and crowdfunding. This new film, while not as imaginatively told, is powerful for its conversations with adivasi women who are leading the fight against corporate land grabs in the state of Chattisgarh.

Rinchin is an activist based in Chattisgarh, and also a writer of fiction for children, in which capacity she was part of the first People’s Literary Festival last year, and joined through a video from Chattisgarh this year too. These details and overlaps are important to note in trying to gain a sense of how the concept of the people is being reworked across overlapping yet disparate contexts. It is an unstable concept, perhaps threatening precisely as it has not been fossilised or achieved firm shape. Some critical narratives of cultural performances/spaces share stark – and very real, vital – images of difference, between the horrific or heroic lives of a poor “people”, and the relative comfort of even many who write about such suffering. That is, there are various narratives that portray “the people” as a relatively stable category, opposed to another stable category – often one of middle class consumption. For instance, a fair amount of writing associated with some of those discussed in this two-part article regularly deride conversations or screenings in “air conditioned halls” – a marker of privilege. While that criticism is valid and required, it is often accompanied by a lack of attention to how such privilege informs many of their own organisers’ lives or pasts too. In drawing attention to such features, I hope to suggest that organising together has a transformative potential as “people” are articulated from different positions, trying to jostle with each other in forming themselves anew.

However, not all films in the People’s Film Festival were as exciting in provoking such questions. For instance, We, The People, by the National Award winning director Samarth Mahajan was a disappointment. The film told the story of three people protesting at Jantar Mantar, and was important in visually recording the spatial dynamics of this site for protests in Delhi. However, it came across as a film made in a great rush. One of the three protagonists of the movie could only speak in Telugu, and was clearly troubled by the pressure of trying to speak in Hindi in front of a camera, and kept saying how she wouldn’t be heard because she couldn’t speak the languages of power, and breaking down in the process. Is it so difficult to find a Telugu translator to accompany one in Delhi? Or at least film her in Telugu and later find someone to subtitle it in other languages? It could be argued, with some justification, that the film was precisely pointing out the fallacy of having one protest space for the national capital where different people are crammed together in non-comprehension, and some voices are more marginalised than others. However, even that could have been shown while allowing the Telugu speaker her voice, without which she is reduced to a mere figuration for an abstract argument. Only the Hindi speaking man and the English-speaking Tamil farmers (the other two protagonists in the film) are heard, and the lone Telugu speaking woman’s voice and concerns are marginalised to illustrate an argument about Delhi’s protest spaces.

There were other instances of not-so-impressive film-making at display in the festival too. And given that occasionally the schedule went off by a bit and the breaks between movies were cancelled, watching back-to-back films was sometimes a strain. Yet, with the overwhelming presence of powerful movies curated for the festival, I could hardly take the chance of leaving the hall before I had to!

Towards Conclusion

As with the two other festivals discussed in the first article as part of this two-part report, entrance to the film festival was free, and the organisers of none of these events accepted corporate, government or NGO funding in organising them. Building on crowd-funding drives launched in advance, members of the audience were requested to donate as may be possible for them, and members of PFC stood near the door with a collection box as people left the hall after a movie. While different movies were made with different kinds of funding – the central government’s Public Service Broadcasting Trust had sponsored a good number of the selections this year, for one – the effort to curate a festival without such direct influences is remarkable. In thinking of the form of little magazines versus films in terms of their negotiation of funding, it is important how such magazines in being cheaper can be more independently produced, but in requiring literacy have a more limited audience than films. The history of these forms and their potential have a long history of being discussed in the region, and PFC’s attempt to curate a festival in these terms marks a promising step taking things forward.

At the same time, the complications of funding are part of the difficulty faced by articulations of the “people”. I began the first piece by quoting an organiser of the little magazine festival. He also used to make films earlier, but gave it up primarily because it was so funding dependent, in a way he felt was constraining for his political expressions. With one’s hands necessarily tied in some ways by the funds, or with access to audiences limited in one way or the other, there is obviously no outside space to corporate India, from where to articulate a people through cultural work. Nor is the category of the people itself so homogenous – for instance the participants at the People’s Literary Festival would themselves be hierarchized by different kinds of privilege, while still being invited as part of panels on “people’s literature,” for conversations often in English. Further, individual members of these organisations involved in trying to build such alternative spaces often need to rely on different kinds of funding and corporate spaces themselves (aside from their workplaces, that is, since many of the people involved work regular jobs for their living) – whether it be in writing for mainstream newspapers, for their research, films, etc. While many hold purist positions of an outside space, it is also registered by participants that the situation is very complicated, and one has to make do with the tools at hand. It is an important part of the fightback therefore to come together as collectives and with such events or otherwise create spaces whereby we can transcend the need for other institutional reliance and constraints, and build different aesthetics and communities, build towards a different society.

Indeed, how the concept of the “people” has these various instabilities and tensions woven into it has been discussed in various contexts by different scholars- from Howard Zinn about USA, to Georgio Agamben about Europe, to Linda T. Smith about indigenous people in Australia, to Margaret Canovan in discussing populism, and many others. There has also been a wide plethora of work on shifting notions of a people in Indian contexts – from Partha Chatterjee on peasants to Nadini Sundar on adivasis, and various others. Though it will not be possible to do so here, engaging with that scholarship more substantively in a scene so live with articulations of this concept, would be a very valuable project to undertake. While informed by that scholarship, my attempt here has primarily been the other way round – to report on contemporary articulations around three specific events that bring a variety of different threads together, but are sparsely discussed in these academic contexts.

In the build-up to the film festival, colourful posters could be seen in different parts of the city, as would again be the case for the People’s Literary Festival in February. Between these various events, the city was full of iterations of “people” and alternative cultural spaces through the winter. While Kolkata witnessed a sling of new corporate literary festivals, and media coverage of the same (even critical attention is attention, after all), BSN’s festival, or the little magazine festival, didn’t get such attention. Even the government sponsored little magazine festival – which includes most of those who participate in the alternative festival – hardly gets much media attention. The issue is also structural: there is only one privately maintained little magazine library in Kolkata, translations between Indian languages are barely taken seriously, and so on. In these times of an ascendant Hindutva and the right-wing, with a marginalisation of dissent and alternative spaces, the lack of reportage or scholarly discussion of such events and forms is part of the silencing. Such silencing contributes to building a dystopic vision of the present, where all is being defeated. In that context, writing an article about one or the other instance of protest inevitably comes across as rare aberrations or tragedies foretold. In fact, for anyone in the city willing to see, alternatives – new and old – were in full bloom through winter.

Nor, in truth, are they limited simply to winters – all of these groups have a variety of activities through the year. Bastar Solidarity Network organises various discussions, protests and events; People’s Film Collective has different activities related to films or otherwise; little magazines are published through the year. Nor are such year-long activities in Kolkata limited to the groups discussed, by any stretch. Some such activities – such as the leftist kobigaan performers (a local performance tradition in Bengal, including debates through songs) who also took the stage at the literature festival – find space in these events. Other young groups, such as Siren, continue singing songs at railway stations, and performing anti-communal plays across various districts. Alternative theatre festivals too continue, though I was unable to attend some of them this season. And as a friend who is part of BSN pointed out to me – there are “people’s science” events throughout as well.

Simultaneously, many of those involved in building these alternative platforms continue working within some other mainstream spaces as well. The Kolkata Book Fair is a huge event, organised with corporate and government support, which this year reportedly included sales of 21 crore rupees and witnessed 23 lakh footfalls. There were arrangements for bus routes from different parts of the city (of course, some parts more favoured than others!) to ferry the regular traffic throughout the 12 days. It is an event that I have looked forward to from my high-school years, though attended erratically since I’ve mostly been based elsewhere since. This year, as I stood by the little magazine pavilion at the book fair at 9pm on Monday, 11th February, not knowing which year I’d next be in town for the event, the bell rang and announced the end of the book fair and people clapped. Many young participants at the little magazine stalls chanted – ‘asche bochor abar hobe’ (this will happen again next year) – clearly moved by their experience over the last 12 days, and looking for more. It was a remarkable moment for showing how such rituals of marginal practices create their own communities of longing and desire, of wanting more of this. On the one hand, the rituals often get stuck in repetitions and already created circles, failing to build for wider transformations. On the other, in their defiant existence and through new paths, they grow as a threat.

(Abhishek Bhattacharyya (obhishekbolchi@gmail.com) is a doctoral student and activist; all photos are by him. Cover photo: Decorations line the entrance to Jogesh Mime Academy, where the People’s Film Festival was held)