P. Varalakshmi has served as Secretary of the Telugu Revolutionary Writers Association, VIRASAM, which was founded in 1970, from 2012 to 2018. On a visit to Kolkata for the People’s Literary Festival organised by the Bastar Solidarity Network (15-16 February), she sat down for a conversation with Abhishek Bhattacharyya before the second day’s sessions began. In this wide ranging interview she discusses the work of VIRASAM, her literary influences, her articles and pamphlets related to environmental activism, the politics of engaging different festival or publication spaces, and the imprisonment of writers and intellectuals in India today.

A: To begin with, I wanted to ask, since you’ve been part of leading VIRASAM (Viplava Rachayitala Sangham) for 6 years, and have been thinking with a cultural organisation of such a scale, which was also formed in 1970 against a different kind of state supported literature festival, and this current festival is being celebrated against corporate literature festivals – how do relate the space you’re coming from to the space you’re coming to?

V: I came here as a representative from VIRASAM. It is a good forum. We were actually thinking of something like this when we boycotted the government organised literature festival in Hyderabad last year. In VIRASAM’s history this was the third time. Firstly, when Sri Sri was founding president, and in the context of the Srikakulam struggle against the brutal onslaught of the government on people, leaders and poets of revolution, VIRASAM boycotted the world Telugu literary conference stating that it is organised by blood soaked hands. And a second time in 2012 December, during my tenure as Secretary, when the Telangana statehood struggle was raging, and as usual there were many encounter killings and unanswered questions by the state, we called for a boycott. Most of the Telangana activists came along with us. And people who are genuinely interested in language and literature, in Telugu language. When the government is acting in the interests of corporates and does not respect any local languages or cultures and related things, everything is corporatized, there’s English everywhere and no space for Telugu – this kind of environment is there. Actually the ruling class has no concern for people’s culture or people’s language. So in this regard we have boycotted the festival. And lastly, 2016 December, that was the third time, and we held a protest, and were arrested. So there was a question from writers in the Telugu sphere: why can’t you create an alternate forum? We gave an appeal to writers also, to boycott these sponsored festivals, so they asked about an alternate forum. There has to be a forum for writers to express art and culture … However writers want to reach the masses, take their literature to regular people, so there should be a forum. They said we’re using whatever forum there is, government or corporate, but if you create a forum we also will join. So we were thinking of something like this. And last year I heard about this festival. And Varavara Rao and Kalyan Rao came here last year from VIRASAM. It was good listening to their experiences here. Incidentally Varavara Rao is now in prison. And in that context I want to come here and represent the poets who got arrested, their voice coming out from prison in the form of poetry, in the form of literature. So this is my interest in appearing here now.

A: So you’re also thinking of starting something like this in Hyderabad or elsewhere?

V: We were thinking, but nothing materialised, it was an idea.

A: One important thing you mentioned was about language. A lot of the discussions that are happening here are in English.

V: Ya.

A: And that presents a difficulty in engaging local audiences. In VIRASAM events that I have attended over the last year, the discussions are in Telugu, and visiting speakers are always translated in a summary version. So how do you think these kinds of festivals can work, with people coming from different places? We don’t know each other’s languages, and in that context how do we think one can engage a local audience with visiting writers?

V: This interaction has some limitations, frankly speaking. The communication runs between writers and educators, because usually they know English or Hindi – many people know Hindi as well – so there is a common language for sharing amongst writers. And coming to the masses of people, they would usually know the local language. So these forums generally work as interactions between writers. But at the same time we can engage with sections of the local population. If this is organised in Hyderabad, all Telugu audiences will appear. And interaction between writers is different from interactions with people. People can be involved by conducting this type of literary fests in several places. So this year this is in Kolkata. Another year it could be in Hyderabad, then Chennai, and so on. So people can think that there is a representation of writers all over the country working in the interests of people. There is art and culture and literature in the interests of people. So we can send that message to people, and people also get connected to intellectuals or writers. That’s a way we can work it out.

A: It’s also interesting this concept of the “people”, and the way it’s working. As you’re saying it’s a conversation between limited writers and intellectuals, and it’s about the people, even if so many people can’t be a part of it. And then thinking also of VIRASAM as a “revolutionary” writers’ association: how do you think these concepts of revolution and the people relate, or are different? Or maybe another way to think of it is to ask: so today many people are saying that if there’s the word “revolution” in an organisation’s title, it will scare people off, but you are part of an organisation that does have that word in its name, and so many people continue to be a part of it. How do you think of “revolution” and “people”?

V: Revolution is the ultimate goal, it is the ultimate dream. Of people or … We have so many revolutions. Even the ruling class talks of revolution, but their revolution is different. They say green revolution, blue revolution, they can even say coffee revolution, tea revolution, so there are so many types of revolutions for the corporate interest. In our sense revolution is a complete change. It’s a complete transformation of the system. Everybody talks of transformation, everybody thinks the system should change. Whoever you ask, from any background. So how does it have to change? This a basic question all individuals or forums are thinking with. Where there is oppression, caste system, patriarchy, corporate oppression, displacement – all these things are there. Basic thing is change, transformation of the society. And literally revolution means complete transformation of the system: not just BJP goes and Congress comes, Congress goes and some other party comes, in which the basic structure is not changed. There will be some differences between them, but overall they will be working in corporate interest. So a complete change has to happen, where the government will be led by the people, in the interests of the people, and not by corporates. Everybody thinks of that type of change. So the general sense of revolution is there. And the historical context for VIRASAM is also that it has come as a response to the Srikakulam struggle [1969]. That direct question was posed to writers and intellectuals: where do you stand? All of these things are happening here, they are killing a poet like Subbarao Panigrahi – how do you as writers respond? The peasants were struggling, and intellectuals were supporting them, so automatically the question arose then: where do you stand? In response, famous writers such as Sri Sri, Ravi Sastry, Kutumba Rao came out and stood with the people. That is how VIRASAM was formed. And we are continuing that legacy for 50 years.

P Varalakshmi at the podium at VIRASAM’s 26th General Conference in Mahbubnagar, held on 13th and 14th January, 2018.

A: Could you discuss some specific initiatives by VIRASAM over the last 5, 6 years towards this end? I’m thinking, given this deep organisational experience that you have – which writers in other regions may not have – what kinds of initiatives do you take as an organisation of writers? What does being an organisation help you do?

V: It’s the difference between individual and collective practise. The latter is necessarily something else – that is a basic thing. In the case of literature, the writer is writing as an individual, the art of writing is an individual’s imagination, but that individual mind should be engaged with a group, and that group should be engaged with the people. So how to learn from the experiences of the people, and how and through what perspectives to write that – we have continuous discussions about such questions. We conduct workshops for writing stories. What kinds of stories are essential now? For poetry, what types of expressions? We work towards new expressions, taking the expressions down to earth, towards the people. VIRASAM has initiated revolutionary songs. The early leaders of VIRASAM, such as Cherabanda Raju – he used to write songs, which were sung at rallies and elsewhere, there was a big following. After that only Jana Natya Mandali came. VIRASAM initiated a move from poetry to song. Poetry can be read by educated or elite sections, whereas songs can travel far and wide. That experiment was done in the 70s itself. By then Jana Natya Mandali was in existence. After that we tried for some stage plays also.

A: In 70s you were doing plays?

V: In 70s, 80s. Now also, some team of young VIRASAM members are doing them.

A: Those are the short twenty minute plays?

V: Yes, they are short plays.

A: For example, there is that one about fighting Hindutva?

V: Ya, and regarding the Basaguda incident also. Since the last 2/3 years we have started a YouTube channel as well. [There is also a Facebook page and Twitter profile]

A: So who attends these workshops you run? Is it like you go to villages and train local people to write? Or is this more internal – you are talking to each other as members of VIRASAM about how to write?

V: Workshops are for writers, not only members. We have other writer friends who attend. We invite writers. And in general students or people interested in literature come to our workshops, and they start writing stories. Workshops are also acting as platforms for young writers to emerge. They are already people interested in literature when they come to the workshop. And actually what goes on in the mind of a writer while creating a story – that kind of thing they can access through our workshops. A workshop lasts for 2-3 days, and discussion goes on. So through VIRASAM so many new writers have emerged.

[For the curious: VIRASAM conducted a workshop this February titled “Desi Literature, Sociological History: Marxism” in Nalgonda district, Telangana. An English report; a Telugu article by the writer Pani, VIRASAM’s State Secretary]

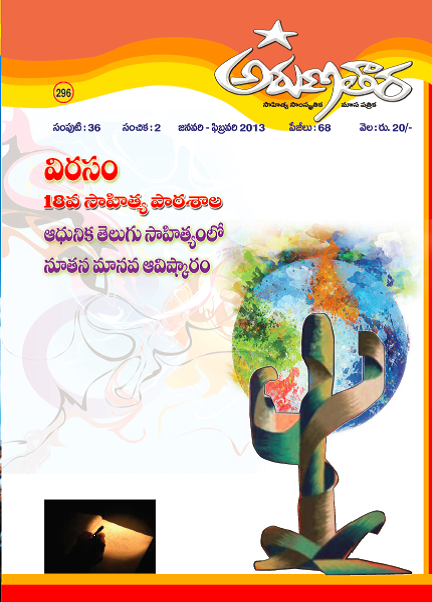

Cover of January-February 2013 issue of the magazine “Aruna Tara” (Red Star) , announcing an overall focus on covering VIRASAM’s 18th literature workshop, held in Hyderabad. The issue contains a report-back and photos from the event. P. Varalakshmi’s editorial in this issue is titled “Kashmiriyat – Afzal Guru”

A: And VIRASAM also publishes so much, it translates so much, and it republishes so much – which is also a big part of its work. Because radical literature is often not so easily available, but because you publish tons there is a lot that can be read. And also when you are coming together as a group you are developing literary criticism, so you are influencing how literature is generally written.

V: Ya.

A: So moving away from the organisational part of it, towards your own work, if we could talk a bit about how you came to be a writer. What kinds of writers would you say influence your writing?

V: There are many. Actually, I’m very influenced by Russian writers. Stories. Maxim Gorky is one of my favourite writers. I used to read so much of Russian stories since my school days.

A: Yes, Gorky’s stories for kids are something!

V: Yes, you know, these Russian stories have created 2-3 generations of writers. They have sensitised us.

A: So these were the Soviet publications?

V: Yes, they were.

A: So your family was a leftist family in general?

V: No, not at all. They are not related to any politics. But we read many books at home and in school. Actually father encouraged us to read more – in order to gain knowledge, not pertaining to some academic things, but to gather more knowledge. I think Russian books were available very cheap, for one or two rupees. So we used to buy them. Those are my first impressions of literature. I read Chalam, Sri Sri, Kutumba Rao when I was in college, I used to issue them from libraries. My orientation is entirely from the world of books. There was no activism in our family or in our town also. So I am influenced by literature, some sensitive literature that touches the heart of women, such as Chalam, and some terrific revolutionary poems by Sri Sri, I used to read all this stuff. When I was studying in Tirupathi I could meet some activist friends there, and I met Tripuraneni Madhusudanarao, he was called TMS. He was one of the earlier leaders of VIRASAM. He actually taught Marxism to us, a group of students – I accidentally had access to that group. I learnt some primary things about Marxism. I admire it as a beautiful science. I read some Marxist classics also. In the process my orientation changed by the time I was doing a postgraduate degree. I saw Marxism as a science which can define the society and give some tools to understand the system and also change it.

A: Chalam and Sri Sri you were reading even before you were introduced to Marxism as such?

V: Ya.

A: So Chalam is famous for his novels, and Sri Sri for his poetry. How did you come to Telugu short stories? You write a lot of short fiction?

V: Not so much. I have written less than ten stories. I generally write articles. When we read and get interested in literature we are not so limited by genre, no, we go to libraries and find different things. Like that Sri Sri is a famous name, and inside a classroom also you hear about him, we had his poetry in our Telugu textbook also.

A: So you did a Masters in Telugu literature?

V: No no, we used to have Telugu as a second language, at intermediate and degree level. Sri Sri is a very well-known name.

A: Of course. Even when I did my BA in literature in Delhi, we had him in our syllabus. But what was your degree on?

V: I was in the sciences.

A: So is that something you continued with, in your writing? Do you write articles about scientific matters as well?

V: Ya, I write about the environment. That is another of my areas of interest: environmental studies. I am actually teaching environmental studies at a private engineering college these days.

A: How come you got interested in questions of environment? Because environment and the left is in one sense a new thing here. I know that CPI-ML Janashakti was formed in 1992 and started talking about the environment at an organisational level. And in a way it’s not something so many leftist revolutionary writers are writing about, while of course many also are. How did you come to think of writing on the environment?

V: Since my academic degrees are a BSc and a MSc, I could easily relate to scientific discussions. So when I joined VIRASAM, and even before, there was so much ongoing discussion related to the environment: regarding displacement, pollution, and so on. And when I read those things I could understand them better relative to literature students.

A: When did you join VIRASAM?

V: 2005. And at my place also, in Kadapa district, there was a proposal for Uranium mining. So as it happened I went to that village with some of my human rights activist friends, and we started reading about the issues, about how Uranium radioactivity works … so to explain to the people also you need to write in a simple language, technical language has to be transformed. That’s how I started writing about the environment, to communicate these issues to people – about radioactivity, radioactive pollution, radiation, renewable energy. And it is just not enough to explain these technical terms related to science. There is a basic political economy behind this, which works in the interests of corporates. One needs to explain that also. Marxism helps in that way. So I could view it in a real sense.

A: So you write a lot of articles. One question that keeps coming up in this regard is where one publishes such interventions. I suppose in a sense it’s about this festival also, and how do you reach people. I know that you work with Aruna Tara (Red Star) and other such magazines, and from there try to create your own spaces from where such voices can be heard. How do you negotiate mainstream publications which give you a different kind of audience, or do you completely abandon them?

V: No, actually we send it to some mainstream dailies also. But gradually the space for progressive voices in the mainstream is diminishing. Occasionally they get published there too. But we can’t completely depend on them, we also need our forum. Aruna Tara plays that role, and as I was saying we have a website also. We are writing on that website. And I think pamphlets go easily to people. Wherever you go you can take some pack of pamphlets. I wrote a number of pamphlets, in the name of the organisation. So Telugu people, in the states of AP and Telangana, they are very interested to read what VIRASAM comments on various matters. When anything happens, people wait for our comments. How to analyse this? How to understand this? So when the Hyderabad Central University incident happened, Rohith Vemula committed suicide, I was thinking of writing a story, and then I saw so much of the negative propaganda, and felt it would be better to write a pamphlet and distribute it widely. I wrote it and distributed it in so many colleges, to convince young people. So you actually have to search for alternate forums, because your space is shrinking more and more in the mainstream.

A: Yes. But what do you feel about still engaging the mainstream presses? Is it a bit like the corporate festivals? So writers also go to corporate festivals – do you think this is comparable? Is it different? How do you feel about that? You must have discussed this as a collective – regarding engaging such spaces? Why is it important to publish in the mainstream?

V: We see it in a different way. A daily paper and a corporate festival, they are not alike. Daily papers – their purpose is to give news to the people. Whatever their influences – corporations or parties – newspapers are actually a thing to circulate news. (laughs) So basically, they have promised to tell us the truth. So we say: you publish this also. We have actually a right to demand that space. But the corporate festivals: their basic project is not literature. They are into mining activities, they are polluting the environment, they are displacing people – and there is a nice cover up with literary festivals and books they publish. So they invite writers to a big dais. Most of the writers are satisfied when they are invited to such a stage, and get an applause. When writers get such a forum to reach people, they feel satisfied. What we are saying is: when you are standing on a corporate dais, how can you speak in the interests of people? Automatically there comes a limitation. And another thing is, these big corporate forums, they are occupying all the space, they are trying to engage all the writers in their forums. So that no one is left outside to comment on or question them. Same thing the government is also doing, so there are writers at academies. We see a lot of difference when a writer is writing independently, and then he goes to say Sahitya Akademy, his voice changes. That difference we can easily recognise.

A: But these big presses, they don’t edit your articles like that? For instance, if I’m not mistaken, Eenadu is also connected to Reliance, so that is also a big corporation using a prominent Telugu daily in a comparable way. They also must have some kind of curtailment of what you write?

V: No, that’s why, where they are engaged with big companies, the space is becoming less and less. And the newspapers are such that there is one newspaper for the opposition party, and one for the ruling party. So the opposition party gives us space, because they have to displace the government. After some time they change places, and one becomes the opposition and the other ruling. But sometimes there are news that no paper will risk publishing.

A: But you don’t risk legitimising the opposition by doing that? Because your voice has a certain weight, so when you write with an opposition party, what are the risks?

V: No we don’t appease any party, but our orientation is towards criticising those in the government. And while we criticise or question the ruling party, the general comment we make is that all parties are alike. So even the party that supports the paper we are publishing in, we will criticise them. Sometimes they remove that line, occasionally that happens. (laughs)

A: Returning to your own writing, is it available in translation for non-Telugu readers?

V: Till now no translation is there. Some friends are asking for translations. So many VIRASAM publications are available only in Telugu. That is a major drawback of ours, we are thinking seriously about translation also. If it’s done in English, then automatically it can be done in other languages.

P Varalakshmi in red at the People’s Literary Festival, Kolkata (15-16 February, 2019). To her right, human rights activist Nilanjan Dutta, moderator. To her left, with the mike, Dr. Shah Alam Khan, author of The Man with the White Beard . To his left, historian Professor Uma Chakravarty. The panel was titled: “Bol Ke Lab Azad Hai Tere: Literature Against Fascism and Imperialism”. Photo courtesy Bastar Solidarity Network – Kolkata Chapter.

A: In terms of you coming to a festival like this in Kolkata, are you also going to other festivals elsewhere?

V: This is my first All-India level literary conference. So this is a new kind of experience!

[Telugu readers may also find her piece on the festival of interest, published 2nd March]

A: So how has your experience been, this past one day?

V: Yesterday there were very good panels. I was very disappointed when two of the Pakistani writers couldn’t appear as their visas were refused. Overall there were good discussions – different people came from different parts of the country, and I met some very fine personalities, it’s actually a very good platform for me, and it opens doors to access these writers in the future also.

A: Is there anything else you would like to say, whether about your own writing, or literary culture in general?

V: In general, today freedom of expression is greatly curtailed, and we are talking about a fascist regime here. So the writers who were supposed to appear here and share their poetry and writings, they are in jail. I am seriously concerned about Varavara Rao and other intellectuals who are there in prison. And I’m more concerned regarding Saibaba. He is in a pathetic condition in jail, he can collapse anytime. So yesterday I spoke about his poetry too, when I was on stage. Immediately writers and intellectuals of all fora have to raise their voices, to save the life of Saibaba, and all the poets and intellectuals who are in jails. That is the immediate task in front of us.

(Abhishek Bhattacharyya (obhishekbolchi@gmail.com) is a doctoral student and activist; all photos are by him, except where specified otherwise. Cover image: VIRASAM posters on a wall in Mahbubnagar announce their 26th general conference, on 13th-14th January, 2018 – the overall theme being to fight “Brahminical Hindu fascism”)

[…] writing from around the Indian subcontinent. The over twenty speakers ranged from members of the Revolutionary Writers Association of Andhra and Telangana, to the initiator of Miya poetry in Assam, to a writer from Kashmir, to […]