On 8th February, Sudip Chongdar, a political prisoner incarcerated in Calcutta Presidency Jail (official euphemism: ‘Correction Home’) died of a brain hemorrhage in MR Bangur Hospital in the city. Sudip, known better by his nom de guerre Kanchan, hailed from Garbeta in the West Medinipur district, was booked and imprisoned under the UAPA (‘Unlawful Activities Prevention Act’) in 2009.* This brought to the fore again questions regarding custodial torture institutionalised in the Indian penal system. A GX report.

Sudip Chongdar was an active and well-known leader of the massive people’s uprising in Jangalmahal’s Lalgarh last decade, as well as the State Secretary of the CPI (Maoists). Chongdar’s death has been called by many as the latest ‘custodial killing’ in the state. A cardiac and high blood pressure patient, Chongdar’s access to crucial medication was allegedly stopped by jail authorities for a few days, leading to a cerebral attack. Chongdar.

The jail authorities admitted there was a massive shortage of the required medicine, which took a toll on Chongdar’s health. He was held in solitary confinement and it was reported that he suffered a massive stroke on 4 February and was found unconscious in his cell. The reluctant jail authorities allegedly didn’t want to shift him to a hospital immediately and allowed his situation to deteriorate. Later, fearing a public outcry, the TMC-led government ordered the jail authorities to take Chongdar to Bangur Hospital, where he was deprived of proper medical attention.

Chongdar is not the first such prisoner who has been allowed to die in custody. Swapan Dasgupta, journalist and publisher of Bengali People’s March was allegedly killed in jail custody under the CPI(M)-led Left Front government in February 2010. He was also arrested in October 2009 under UAPA and was denied proper medical care during his custody. Ranjit Murmu and Tarun Saha, two tribal Maoist leaders, were also among those allegedly killed while in custody under the West Bengal Government. Incidentally, Chongdar was an under-trial prisoner, even after a decade of incarceration. He was active not only in Lalgarh, but also in Nandigram and Singur, and had later allied with the TMC. It is believed that the TMC Government did not want to start the trial for fear of details of its past association with the Maoists coming out in public.

History of torture

Custodial torture is as old as the idea of a police force itself. On the one hand, there are Sections 25 and 26 in The Indian Evidence Act, 1872 that make confessions in police custody unacceptable as evidence, as a legal attempt to disincentivize custodial torture. “No confession made to a police officer [or in the custody of a police officer], shall be proved as against a person accused of any offence,” says Section 25 [Section 26]. On the other hand, the infamous Terrorist and Disruptive Activities (Prevention) Act – TADA – had in it ‘Section 15’ that says, “Notwithstanding anything in the Code or in the Indian Evidence Act, 1872, but subject to the provisions of this section, a confession made by a person before a police officer not lower in rank than a Superintendent of Police … shall be admissible in the trial of such person [or co-accused, abettor or conspirator]”. The TADA was subsequently replaced by the equally infamous Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA). The POTA retained in it a ‘Section 32’ that is almost a verbatim copy of Section 15 of TADA, with some minor extra stipulations about recording such ‘confessions’, etc., that are in practice never followed or at even brought under public scrutiny. Most recently, the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act (UAPA), under which Sudip Chongdar was held, has a clause called the “Protection of Action taken in Good Faith”. No suit, prosecution or other legal proceeding shall lie against anyone in the Central or State Governments or District Magistrate, “for anything which is in good faith done or purported to be done in pursuance of this Act or any rule or order made thereunder” [emphasis: GX]. Under laws like TADA, POTA, and the UAPA, ‘confessions’ continued to form the basis of trials, and allegations of custodial torture kept piling up concurrently. Many of the 2006 Bombay train blast accused have alleged custodial torture. In case of some of the accused, the only ‘evidence’ produced by the investigating agency against them in the MCOCA trial, was their ‘confession statement’, at times in a language they don’t even speak. And on the basis of such trials, people have been kept in jail for decades.

India had signed the UN Convention against Torture in 1997. However, ratifying (the most crucial aspect of the commitment that involves taking legal steps to make Indian laws correspond to the UN convention commitments) has still not been done. In 2008, a Prevention of Torture Bill was brought in Parliament, but due to its weak provisions was sent to a select committee. The select committee draft was presented in the Rajya Sabha in 2010, but it hasn’t been moved since.

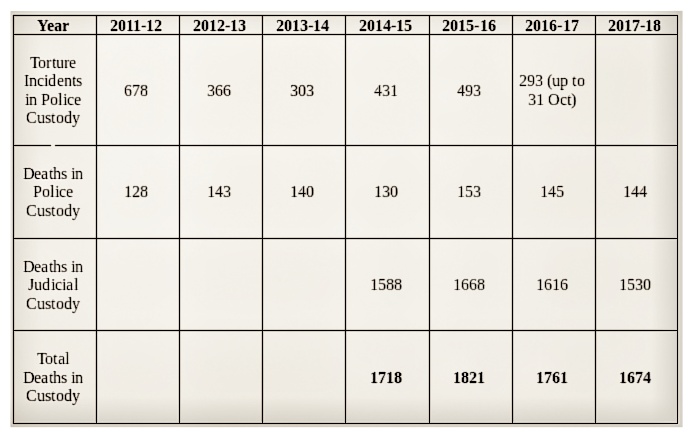

In March 2018, Minister of State for Home Affairs Shri Hansraj Gangaram Ahir, while replying to a question in the Rajya Sabha, mentioned that the National Human Rights Commission (NHRC) registered a total of 1,674 cases of custodial deaths (comprising 1,530 deaths in judicial custody and 144 deaths in police custody) from 1 April 2017 to 28 February 2018. That’s over five deaths in custody every single day.

Chilling accounts of torture from recent times

On 3rd April, 2018, miscreants forcefully entered the house of Devender, father of an underage rape victim in Unnao, UP, and thrashed him brutally in front of his family members. Prior to this assault, Devender’s daughter had accused BJP MLA Kuldeep Singh Sengar and his brothers of gangrape. The family approached the Makhi police station to lodge an FIR against the younger brother of the MLA and his aides, alleging that they were behind the rape and the subsequent attack on the victim’s father. The FIR had been reportedly lodged but allegedly did not mention the name of the MLA’s brother. In a bizarre turn of events, the police booked Devender under Sections 323, 504, 506 of the IPC and sections of the Arms Act. He was accused by the police of being a listed criminal, then arrested and remanded to judicial custody for 14 days. After a customary medical examination, Devender was sent to prison at 7.30 pm on 4th April, 2018. According to media reports, on 8th April 2018 evening, Devender complained of stomach ache. Later that night he died in the hospital at around 3.30 am. The post mortem report revealed disturbing details. There were 14 injuries, including abrasions, contusions and bruises. “The postmortem report of the 55-year-old listed multiple abrasions near abdomen, buttocks, thighs, above and below knee joints and arms. It, however, listed blood poisoning due to perforation of colon as the cause of death. Perforation of colon, which is a part of intestines, can be caused by a number of diseases. It can also be caused by blunt trauma to the abdomen or a knife or gunshot wound,” said an NDTV report.

In an article that appeared last year on EPW Engage, the following figures based on two of the answers in the Parliament about the use of torture reported by the NHRC were presented.

Again, these are only the number of incidents that have been reported to the NHRC. According to the law, a judicial magistrate must conduct an inquiry into every custodial death, the police must register an FIR, and the death must be investigated by a police station or agency other than the one implicated. Further, every case of custodial death is supposed to be reported to the NHRC. The police are also required to report the findings of the magistrate’s inquiry to the NHRC along with the post-mortem report. NHRC rules call for the autopsy be filmed and the autopsy report to be prepared according to a model form.

However, according to a Human Rights Watch report, these steps are usually ignored. According to government data, a judicial inquiry was conducted in only 31 of the 97 custodial deaths reported in 2015. In 26 of these cases, an autopsy was not even conducted. “In some states, an executive magistrate – who belongs to the executive branch of the government as do the police, and therefore is not independent and is likely to face pressures not to act impartially – conducts the investigation rather than a judicial magistrate”, said the HRW report. Of these 97 custody deaths, police records list only 6 as due to physical assault by police; 34 as suicides, 11 as deaths due to illness, 9 as natural deaths, and 12 as deaths during hospitalization or treatment. However, in many such cases, family members allege that the deaths were the result of torture. In 67 of the 97 deaths, the police either failed to produce the suspects before a magistrate within 24 hours as required by law, or the suspects died within 24 hours of being arrested. “Human Rights Watch is not aware of a single case in which a police official was convicted for a custodial death between 2010 and 2015. Four policemen in Mumbai were convicted in 2016 for the custodial death of a 20-year-old suspect in 2013,” says the report.

The list never ends

In her EPW article, Baljeet Kaur lists 122 incidents of custodial torture based on going through English language news reports available on the internet between September 2017 and June 2018. In total, these 122 incidents led to 30 deaths. In several cases, there were multiple victims. Below is a portion of her list:

[table id=4 /]

Such lists go on and on. Here we will mention one specific report on the so-called “Bhopal Jail Break” and subsequent encounter of the prisoners. Earlier in November 2016, “eight Simi activists fled the Bhopal Central Jail and were subsequently traced and killed by MP police in an encounter” is what was put out in the media, after an extra-judicial encounter of Muslim prisoners in the Bhopal jail. Not only have serious doubts been cast upon the killings, but a barrage of allegations of prison (judicial custody) torture had emerged from the Bhopal jail after the encounters. “It is impossible to jump over those prison walls. ATS Chief himself has said they were unarmed, but they were shot on the chest. Even as the police officers were under investigation, the CM Shivraj Chauhan rewarded them for gallantry!” said Adv Shahid Nadeem who has been fighting this case.

In April 2018, an NHRC investigation confirmed that in Bhopal Central Prison, around 21 Muslim undertrial (except for 1) prisoners were being subjected to torture and solitary confinement. They were allegedly prevented from meeting in private with their families and lawyers – aConstitutional right. The report stated that their copies of the Quran were thrown away, and they were being forced to chant “Jai Shri Ram” in order to receive food. They were not allowed to sleep for more than few hours in the name of attendance (“khairiyat”). The NHRC recommended action against jail officials including prison doctors.

Meanwhile, narratives of Indian prisons acting as mass torture houses keep coming. After Shyamu Singh died in police custody on April 15, 2012, the UP police said that Singh had committed suicide. Singh and his brother were both arrested by the police. His brother said that after their arrest, both were stripped down to their underwear and tortured: “[The police officers] put us down on the floor. Four people held me down and one man poured water down my nose continuously. I couldn’t breathe. Once they stopped on me, they started on Shyamu. Shyamu fell unconscious. So they started worrying and [were] talking among themselves that he is going to die. One of the men got a little packet and put the contents in Shyamu’s mouth,” he said.

Shyamu Singh died in the hospital. After an ‘internal investigation’ the Police dismissed allegations of death from torture. The state CID conducted an investigation and held seven police officers responsible for torturing Singh and poisoning him to death. However, a final inquiry report submitted a year later, in 2015, cleared all seven policemen of any wrongdoing.

Rajib Molla, a 21-year-old vegetable seller, was arrested on February 15, 2014, in West Bengal. He died the same day in police custody. The police said he committed suicide but his wife alleged he died from torture. Molla’s wife said that ever since she sought judicial intervention in the case, powerful men in the area threatened her to withdraw her complaint. Banglar Manabadhikar Suraksha Mancha (MASUM), a non-governmental organization that was supporting her, also reported threats and the detention and beating of one of its staff members.

On 8th February, Sudip Chongdar became the latest in the list of custodial deaths in the country.

———-

* The recent spat between the Modi and Mamata regimes started over the CBI’s sudden attempt to raid the official residence of Rajeev Kumar, the Commissioner of Kolkata Police. Though Kumar’s complicity in the Chit Fund Scam and shielding the who’s who of the TMC is now well documented, it is often forgotten that Kumar played a significant role in the arrest of Sudip Chongdar. Kumar was a part of the erstwhile Left Front government’s administration and played a crucial role in crushing the popular rebellion in the Jangalmahal region of West Medinipur district. Kumar was a part of the Special Task Force that arrested Chongdar and three others from Kolkata’s Maidan area. Then, reports circulated of the captives being tortured by the STF during their custody period.

After the regime-change in 2011, police officers like Kumar switched allegiance immediately, becoming favourites of the new regime and no action was taken against them for their past crimes, just like the CPI(M) promoted and honoured notorious police officers like Ranjit (Runu) Guha Niyogi, Ranjit Guha, Debi Ray, etc, who played a heinous role during the Naxalbari movement of the 1970s. Kumar became a mastermind for most of Banerjee’s pet projects of state violence, including the assassination of Maoist leader Kishenji in November 2011. Today Kumar is being projected as a victim in the name of ‘federalism’, while Chongdar is forced to die in custody.