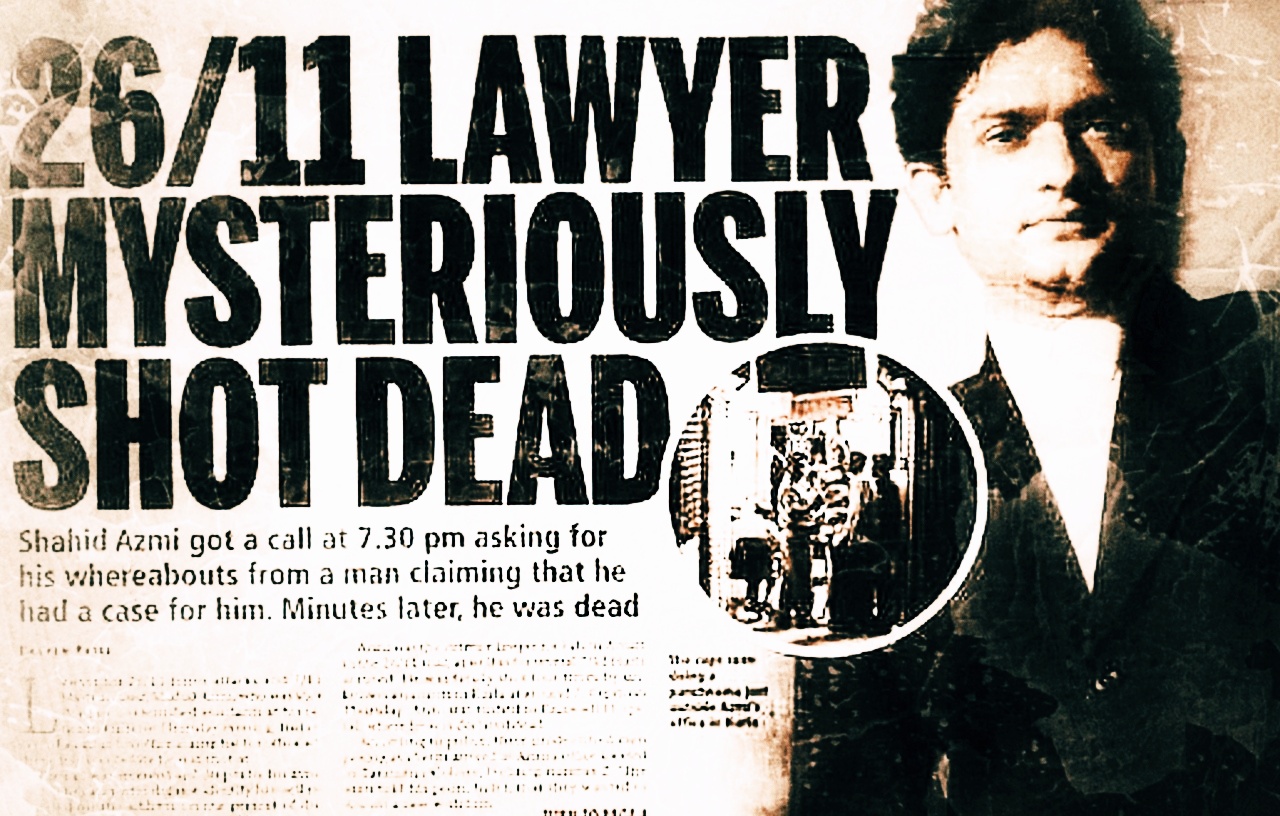

On February 11, 2010, a young Mumbai lawyer, Shahid Azmi, was assassinated in his chamber, by a group of armed men. They entered through the door of his chamber, shot two bullets at his chest, and fled. Shahid was declared dead after being taken to the Rajawadi Hospital in Ghatkopar. Although we still do not know ‘who’ is behind the killing, it is not hard to guess ‘why’ lawyers like Shahid are silenced. A GroundXero report remembering Shahid Azmi’s life and death as a people’s lawyer, on the occasion of his 9th death anniversary.

In his short career as a lawyer, Shahid Azmi took up cases in defense of those he believed were wrongly accused in several high-profile “terror cases” in Mumbai. His first major success came in the 2002 Ghatkopar bus bombing case, when Arif Paanwala, who was arrested under Prevention of Terrorism Act (POTA) and was named the prime accused, was acquitted along with eight others, due to lack of evidence, by the court; this eventually led to the law being repealed.

But Shahid wasn’t just another good lawyer who got trained in law to work for the politically marginalised. He himself had a history of wrongful incarceration, and in many ways it was his own experience that naturally pushed him to take up law as a means to fight for social justice. In December 1992, 15-year old Shahid was arrested for allegedly being part of violent activities post Babri demolition, and booked under TADA. From inside Arthur Road jail, he finished a college degree and a post-graduate course in creative writing, before he was acquitted following a Supreme Court order in 1999. As soon as he reached Mumbai after his release, he reportedly asked his brother to get two forms – one for LLB, another for Journalism. He would go for LLB classes in the morning, and for Journalism classes in the evening. Around the same time, he joined Adv Majid Memon’s office as a junior during the daytime. He also started writing as a journalist for the website India.com. But over time, he zeroed in on pursuing legal practice as his profession.

A people’s lawyer, Shahid was known to work for long hours, pouring over his books, going meticulously through case documents and records. He would visit the spots of the incidents, to understand the details of the case. He would listen to his clients intently, and believed that is the way to gain knowledge and become better as a lawyer. He would charge very minimal fees, because most of his clients were from economically poor backgrounds. He was instrumental in setting up the legal cell of an NGO, Jamat-e-Ulema-e-Hind, in order to fight pro bono cases for people booked under POTA, MCOCA and other such draconian acts. Shahid was an expert on the UAPA and MCOCA (Maharashtra Control of Organised Crime Act). Some of the key cases he was fighting were the Ghatkopar blast case, 26/11 Mumbai attacks, Malegaon blast case, etc. He was also defending some of the accused in the 2006 Bombay train blasts case. He was shot dead only months before the 26/11 judgment came out. Responsible for many acquittals in all these, and other cases, Shahid was labeled as a “terrorist lawyer” by one of the newspapers – the phrase was kept vague, it could either mean a lawyer for terrorists, or a lawyer who is himself a terrorist. Ironically, it is not that he fought only “terror cases”. He took up all kinds of cases that came his way, and where he believed that innocent people were being wrongly accused.

His time as a lawyer was not easy. Throughout his prematurely terminated career, he had to wade his way through hostility from large sections of his lawyer colleagues, and from the media. There were constant smear campaigns run against him. But, with the help of a very small group of friends in the Bar Association, Shahid focused on his work. Many of the judges treated Shahid with respect, since he clearly knew the law and was serious as a lawyer. With time however, he started receiving death threats for his work as a lawyer. He had filed police complaints and petitions in the court, asking for protection. But no protection was given, and the police took no action to trace the threats. Shahid had also tried meeting with the Police Commissioner about this, but allegedly the Commissioner did not meet him.

He also received multiple death threats for his work as a lawyer. He filed police complaints, and petitions in the court, asking for protection. But no protection was given to him, police took no action to trace the threat calls.

The last case argued by Shahid Azmi was the 26/11 case. Mumbai was attacked by 10 armed attackers. 9 of them were killed by police firings, 1 (Ajmal Kasab) was arrested. But the investigating agency also claimed that there were 2 other men – Fahim Ansari and Sabauddin – who made the map and passed it on to Kasab. According to the police, these two people went to Nepal where they prepared the map in a hotel, and handed it over to someone. All this was according to the statement of an “eyewitness” to this whole process. Shahid fought for Fahim Ansari (accused number 2, after Kasab), and he was ultimately acquitted. The “eyewitness’s” account broke down with only a few questions that Shahid asked him during cross-examination. Which hotel were you staying in Nepal? Which hotel were the accused staying in? How did you reach Nepal? Which currency did you use in Nepal? – the witness had no answer to any of Shahid’s questions. By the time the judgment came, he was not alive to see it. Advocate Shahid Azmi had been shot around 6 months before the judgment in the 26/11 Mumbai attacks case was announced.

In his death, by ensuring the acquittal of an innocent, Shahid tried redressing the wrongful incarceration of a 15 year old Muslim boy in a city ravaged by communal riots, 17 years back. A 15 years old Shahid was illegally detained by Bombay police, in 1993 during the riots following Babri Masjid demolition. He had his Board exam the following day, and the police said they would allow him to go write the exam, but he would have to be back under their custody by 2pm, after the exam is over. He knew he would be arrested for good, or falsely implicated in some case. But he still decided to go with them, because he knew that if he didn’t, the police would harass his family. Shahid’s family was his mother, and 4 other brothers two of whom were younger than him. Shahid was right. The police arrested him that day from Shivajinagar, Mumbai at around 10 in the morning as he was preparing to go for the exam. He never got to reach the exam center. Police incidentally claimed they had arrested him from Delhi. His family had no idea of all this. 3 days after his arrest, they came to know about it from the newspaper.

He was reportedly tortured brutally in custody. He would be hung from one hand, till his shoulder dislocated, and this was repeated multiple times. His family would get to know about such torture when someone from the jail would get released, and would come to meet them. On the day of the judgment, when the judge told him “You are free”, he called up his younger brother Khalid, and said “Get me two forms, I am coming home.” He was booked under the draconian TADA. And he had resolved while in jail that he would devote his life fighting against these acts like TADA, POTA, MCOCA, etc.

All these acts are described as “draconian” since they are against the principle of natural justice that says “Innocent until proven guilty”. Under these kinds of acts, arrests can be made on flimsy grounds. For example, if someone already under custody mentions or is claimed to have mentioned X’s name in their “confession”, then X can be arrested. It is very difficult to get bail once these acts are slapped. The time limit for filing the charge-sheet (the report of the police’s primary investigation, that is, the written account of “Why the police thinks X should be under arrest”) is 180 days, instead of the usual 90 days. This means that someone booked under these acts can be kept in prison for 6 months before the police has even officially stated before the court why that person should be kept in jail. MCOCA courtrooms are heavily policed, and are known to be striking terror in the minds of the defendants and their lawyers, as alleged by the family members of the accused in each of these cases. “We have seen with our own eyes that the MCOCA judge is given rides by the ATS officers. What kind of message does this send to the accused and their families about the impartiality of the court?” asked Shahid’s younger brother Khalid, who followed in the footsteps of his brother to become a lawyer himself. It was because of a sincere judge that the Hindu terror organisations behind the Malegaon blasts were brought to justice, and Muslims who had been previously wrongly accused were finally acquitted. But such kinds of judgments are rare exceptions in the climate of overt police control of MCOCA trials. Although acts like the TADA and POTA had to be finally scrapped, largely due to the tireless works by lawyers like Shahid Azmi who brought out the rampant misuse of these laws, they have today been replaced by the UAPA which is being used to incarcerate anyone that the Government declares as “committing crimes against the nation”. UAPA has been specifically used to hound human rights activists, anti-caste leaders, worker leaders and lawyers, like the recent arrests post the Bhima Koregaon attack on Maharashtra dalits.

On 11th February 2010, four gunmen entered Shahid’s law chamber in Taximen’s colony, Kurla, and shot him dead. He was only 32 then. While describing the shock upon receiving a message from a friend saying “Where are you? Your brother has been shot!”, Khalid mentioned that Shahid had told him, “Today or tomorrow I will be killed. The Agency is after me, and they don’t want the facts to come out.” Shahid told his brother he was not sure how much time he had left with him, and gave him a list of a few phone numbers of people he should trust and contact for help, in case something were to happen to him. “There are the phone threats, but there is also this silent threat that always looms. You are not threatened explicitly, but you know that you are being watched and pursued,” he reportedly told his brother. The Bar Association of Bombay High Court conducted a condolence meeting, but did very little to ensure that justice is served in the case of one of their member’s murder. They had passed a resolution declaring no lawyer registered with the Bar Association will defend the accused in court, but later they themselves violated this.

As a tragic irony, Shahid’s death perhaps led to more people knowing about his work and life, than what was known about him while he was alive. Several young students of law approached his family and colleagues, to know more about him as a lawyer. “I want to become a lawyer like Shahid,” many of them would say. There were many who decided to pursue law, drawing inspiration from Shahid’s life. Several of them did indeed graduate with their law degrees, and are now pursuing their career as lawyers. Many have taken up cases for who they think are falsely implicated under draconian laws. “It was really he (Shahid) who sowed these seeds and watered them. Now the tree has grown and fruits have come, and he is not around to see it. It is another thing that at the same time, several others are reaping those fruits for their own selfish interests,” said Khalid, alleging that the case for bringing Shahid’s murderers to justice was not pursued by the legal cell he himself helped create and run. One of the accused has gotten bail since, and now that almost a decade has gone by after Shahid’s murder, chances are very bleak that we will ever find out who really was behind the assassination. Reportedly, even in the 2006 Bombay train blasts case, many of Shahid’s affidavits were not brought on record subsequently by the other lawyers involved in the case, and many of his consultations were not pursued. He argued that MCOCA was not applicable in this case, but he remained unheard. Khalid, who was also an active member of the legal cell, and was actively organising legal support for the vulnerable across the country, including Gujarat, Calcutta, Karnataka, Kashmir, etc., subsequently quit it. “People are now earning in crores, using my brother’s name and his hard work,” Khalid alleged.

As a tragic irony, Shahid’s death perhaps led to more people knowing about his work and life, than what was known about him while he was alive. Several young students of law approached his family and colleagues, to know more about him as a lawyer. “I want to become a lawyer like Shahid,” many of them would say.

Shahid was not just a good, hardworking, sharp lawyer, but he was also a ‘practical lawyer’. His own experience of being wrongly jailed as a minor under a law like TADA, shaped his pragmatism of what works and what does not. He trained himself in jail. He passed his 12th exam, and graduation from jail, and also obtained certificates in Computer skills and Language skills including Marathi and English. By the time he got out of jail, he was fully prepared in his mind for the fight he would put up for the rest of his life. While studying law, he was again pulled up by the Calcutta police in relation to the shooting at the American Embassy in Calcutta. He was flown from Bombay to Calcutta as a single passenger in the flight, and the Army came to “receive” him. Eventually they had nothing that could connect him in anyway with the shootings, so he was released.

His death shook the entire family – emotionally and financially. His mother, who was already a patient, went into depression following her son’s death. “The months of February and March even now are when our mother slips into depression. This time of the year is still a trauma for her, and she has to fight very hard to cope with it,” said another of Shahid’s brothers. Shahid’s death shook not just his own family, but also those of the people he was fighting for. Within a couple of weeks after his death, his brother Khalid, by now a lawyer himself, had to end his own mourning, and take up Shahid’s unfinished cases, including 26/11, Malegaon, 7/11, etc. “I had to take this decision that I must keep up the fight my brother started,” Khalid says.