The All India Union of Forest Working People and Delhi Solidarity Group organized a public hearing at the Constitution Club of India to talk about the increasing incarceration of women, the prison conditions, and the targeting of women from specific communities. Women spoke of their experiences in prisons across the country, from Tamil Nadu to Chattisgarh to Kashmir. Avantika Tewari reports on what was discussed, and the importance of the call for prison abolition.

With a steady rise in the incarceration rate of women over the last fifteen years, and with only 18 jails out of the 1401 in the country reserved for women, it seems rather obvious to ask – how do these 18 jails hold 2985 female prisoners? Most of the women inmates are housed in women’s enclosures of general prisons designed in colonial times to keep ‘delinquent’ men and freedom fighters. According to the Commonwealth Human Rights Initiative (CHRI) Report 2015, globally, the number of women and girls in prison have increased by 50 percent in the past 15 years. India, too, has seen an increase in the number of women prisoners. In 2001, 11094 women inmates formed 3.5 percent of the prison population. 15 years later, Indian prisons house 17834 women inmates — an increase of 61 percent — with their share in prison population having gone up to 4.3 percent.

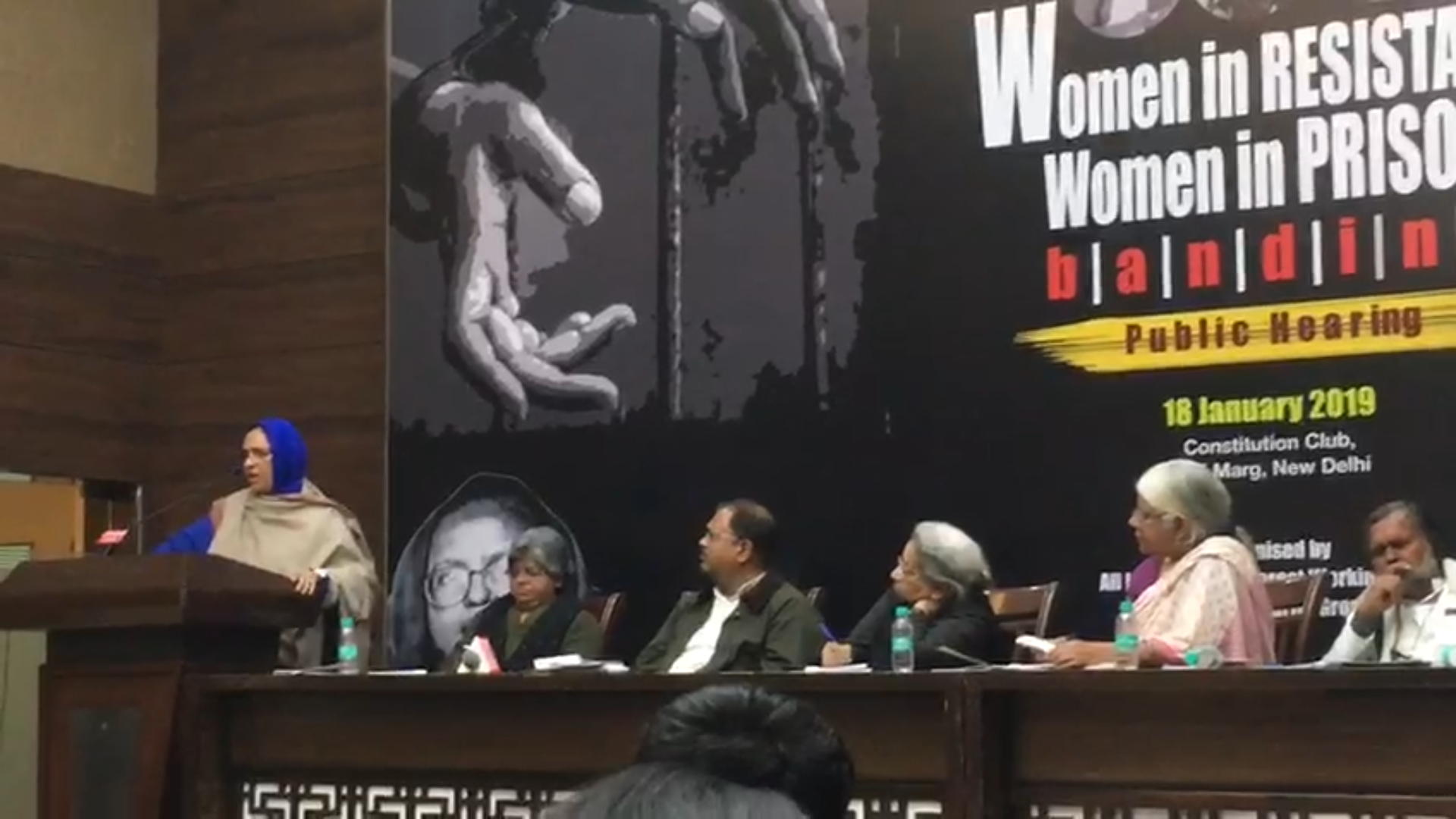

On 18th January, 2019, All Indian Union of Forest Working People and Delhi Solidarity Group organized a public hearing at the Constitution Club of India. Soni Sori from Chhatisgarh, Manorama Khatua and Harabati Gando from Odisha, Sokalo Gond, Rajkumari, Sobha, Lalti, Kismati, Phulri from Uttar Pradesh, Xavieramma from Tamill Nadu, Anjum Zamrud Habib from Kashmir, Nikita from Jagdalpur Legal Aid and Sweta Daga shared their experiences with the assembled crowd. The panel also included Uma Chakravarty, Vrinda Grover, Vikas Narayan, Prafulla Samantara and Bela Bhatia. Teesta Setalvad was expected to join the jury but couldn’t make it to the event due to personal reasons. The public hearing was initiated in memory of Bharti Roy Chaudhary, who was one of the founding members of the National Forum of Forest Working People and Uttar Pradesh Land Right and Labour Rights Campaign Committee.

The Making of a Mythical Criminal

“Jail is for politically conscious women. Jail se matt daro!”

Anjum Zamrud Habib

A range of immediate and long term solutions arose from the sharing of prison experiences – relating to prison rights, prison reform, bettering prison conditions, and to articulating a political imagination of prison abolition when prison has come to be a political holding place to crush resistance. One can anticipate from the life and loss of different women such as Mathura and Thangjam Manorama that to be in direct confrontation with the security apparatus of the State means being vulnerable to custodial rape, torture, denial of health services, lack of clean food, bonded labour, experiencing daily humiliation and more.

Incidentally, it is after the 2006 Forest Rights Act – which was to precisely correct the wrongs of the previous Forest Act of 1927 by recognizing the rights of traditional forest dwelling communities over the land, without branding them as ‘encroachers’ to serve the end of dispossessing them of their land – that the number of cases against tribal communities has actually increased, said Roma Malik, Deputy General Secretary of the All India Union of Forest Working People. Despite the law being on the side of people, talking about the right of the community over their land, the same law is being used to further incarcerate them. In places like Lakhimpur Khiri, Sonbadhra, including other forest areas of Uttar Pradesh, women have been falsely accused of cutting trees and booked under the Forest Act, along with other charges under the Indian penal code. What makes their trials endless is also this precise practice of putting double cases – leaving most women languishing in jail for years, under trial – the trial is the punishment.

Tangentially, Roma remembers the curious case of forgery that witnessed the transformation of Kismati to a Manju. How miraculously, all Manjus become this Manju and how Kismati’s very identity despite the promise of identity ‘proof,’ stood erased when a criminal charge sheet was being manufactured before her eyes. Kismati witnessed her own unmaking and was forced to assume a new name, Manju. Her village’s Pradhan testified to her being Manju, and that was enough, as against all the ‘Adhaars’ (markers of identity in documentation) that say otherwise. How fickle is the promise of democracy, how hollow its claims! The real tragedy though is that not only does Kismati get incarcerated, but due to a variety of compulsions she has to also actively participate in the making of her own myth, in the construction of the fabricated case. Kismati is no exception in being a victim of lost identity.

Parallels can be drawn to extend the inner logic of manufactured cases to show how most of the encounters of villagers in Bastar is given the appearance of gunned down ‘Maoists,’ or ‘Jihadis’ in Kashmir. So shoddy is the job of the State, so emboldened their lies that they have increasingly stopped bothering to even clean up its tracks – recall, when the National Investigation Agency had busted, what it claimed to be an ISIS inspired group of 10 people, with Sutli bombs (firecrackers) presented as part of the evidence of the ‘explosives’ recovered in the raid. Anjum Habib, who was falsely implicated under POTA in 2003 and was jailed and released in the winter of 2007, succinctly captured this phenomenon in a phrase, “Special Cells ki Specialty Hoti hai Kashmiriyon ko bandd karna.”

Anjum Habib speaks about the silence around Kashmir, her long years in prison, and more. Photo: Avantika.

Law as Weapon of Warfare: Trial as Punishment

“I was in jail because I fought for my land, not because I committed a crime. I wasn’t afraid of jail then and I’m not afraid of it now.”

Rajkumari, from the Bhuiya Adhivasi Community in Dhuma village of Sonbhadra district of Uttar Pradesh, who was jailed in 2015 for participating in protests against the Kanhar irrigation project.

Vrinda pointed out how we need to correct the myopic idea that the police botches up cases as an exception, while accepting the unstated premise that the police and the State have used in conflict torn areas – the law is a weapon of warfare to criminalise people, especially political activists who are locally fighting the power structures. She backed her claim by using the 2014 report submitted to the Ministry of Tribal Affairs which was prepared by Prof Xaxa, which stated that the encounter of the Adivasi with the law is mediated through criminal law, which effectively means that the Adivasi doesn’t approach the courts of law to make rights-based claims, but is brought to the court through criminal cases that are put on them. Thus, the relationship between the Adivasi and the law-court is one of a purely negative interaction. The situation is so bad that the then Commissioner for Scheduled Castes and Scheduled Tribes, in his 29th Report, said that “The criminalisation of the entire communities in the tribal areas is the darkest blot on the liberal tradition of our country.” (Government of India 1992)

Xavieramma, from the struggle against the Kudankulam Nuclear Power Project in Tirunelveli district of Tamil Nadu, had been framed on charges of sedition and other grave offences. The two-decade-long struggle against setting up of a nuclear plant in Koodankulam, which challenges the fishermen communities’ livelihood and the environment, has not yet moved the governments in power.

The situation is no different outside of the ‘conflict torn regions.’ Roma told us how in UP, for one of the women prisoners, “a habeas corpus petition is filed and the Allahabad court takes three months instead of 24 hours to produce the person before court.” One can see how the law doesn’t even care to maintain the farce of its own procedure anymore and how the liberal-democratic institutions are gradually revealing their thinly veiled ideological orientation.

Most of the Adivasis who are pronounced ‘Naxals’ are then charged with cases under UAPA and/or IPC which have no half-sentences in case of an impending trial, leaving them with nothing. So even though she points out, that there is a provision of Malicious FIR under the Law Commission of India to compensate for the lost time, for when they were under trial in cases in which they were wrongly implicated, such compensation has failed to come through in most cases. Vrinda recounted the case of Khwasi Hidme: Hidme was picked up when she was 15, shuttled between thanas in Sukma, Dantewada, Bhansi, beaten relentlessly, raped, and after eight years acquitted when the charges of ‘Naxal activities’ against her proved false. In 2008, on her way to a fair, Hidme was picked up by the police in a case involving the killing of 23 policemen. As Nikita from the Jagdalpur Legal Aid Group said, quoting Surendra Gadling, who is himself in jail as a token of reward by the State for his struggle to represent those political prisoners whose cases who otherwise find no representation and hearing – “the rule of law is a law of re-arrests.”

Soni Sori speaking at the event:

Tribal Activist Soni Sori Recounts her Horrific Time in Prison

Tribal Activist Soni Sori Recounts her Horrific Time in PrisonSoni Sori speaking at the conference, 'Women in Prison, Women in Resistance,' recounted her experience in jail. She talks about the brutality of the police force and other authorities. She also speaks about the strength and resistance of other women who were in jail with her.

Posted by NewsClick.in on Tuesday, 22 January 2019

Everyday Life of Prison

Jail se darr nahi lagta. Chhadi pade chham chaam, vidya aayi gham gham.”

Kamala Yadav, NAPM

Kismati lamented the pettiness that is engineered within the jails due to the ration-corruption, lack of infrastructure, and run down conditions of the prisons. A prisoner from UP, who was out on bail, shared that about 70 women and 10 children are at present in the Mirzapur jail which she inhabited. So a 20 seater jail is housing 80 persons! Vrinda Grover also pointed out how the Courts of the country had devised a plan to address the overcrowding of jails by suggesting that those inmates who are under trial should be allowed to serve half their punishment term and be allowed out on bail. Yet, this didn’t result in stopping from the jails from spilling over with fresh inmates for more often than not, with the charges leveled on them including a sentence of life imprisonment – which has no half sentence. Moreover, most prisoners are set free only to be rearrested.

It is well imaginable that this deliberate squeezing of space and resources creates a condition for an unpleasant exchange between inmates, giving rise to new antagonisms besides the already existing ones. They would have to fight over every food grain, contestations over a bar of soap, blanket, space, besides simultaneously developing methods and processes of navigating through the chaos, like, taking turns to get a place to sleep, among others. Yet, there would be as they were called, “Dabangg Mahilayein” who will beat their fellow inmates to better their chances of survival within the jail, who would hoard ration, take over more space in jails. Anjum Habib, a former prisoner of Tihar Jail, concurred that the prison economy is no different from the world outside. That the social relations are bound to get replicated inside along caste, class, regional, religious lines even within the jail is no surprise. To ignore that, would be a grave mistake. One needs to remember that while these women are being victimized by the State, they are also simultaneously oppressing those prison inmates they deem ‘below’ them.

Vrinda reminded us that while it is important to talk of prison reforms, demands of reforms don’t hit the prison complex where it should hurt. For, ultimately, it is also for managerial and administrative reasons that the jail authorities will find some ‘reform’ essential to enhance its own efficiency. One such reason lies in the fear jail authorities have of riots and jail break. But for the political struggle, the end goal cannot be limited to piecemeal bargains.

In fact, Soni Sori, showed us how these struggles are constantly waged within the jails and have also found success without ‘outside intervention.’ When women prisoners have acted in concert, their incipient power has brought positive changes despite the repressive character of the State machinery. In the Jail Andolan which was carried out in Jagdalpur Jail, prisoners refused to perform labour without wages, refusing to carry out cleaning of sewers, raising a voice against ration-corruption, demanding better quality food and water. It is here that Vrinda, too, suggests that the civil society must make legal interventions. She highlights how the Ahmedabad Court’s judgment rejecting minimum wage to prison workers must be challenged.

Sori, Kismati and Xavieramma all spoke about the kind of work that inmates are forced to carry out – for example, they are made to jump into sewers without being given any access to health facilities. The women complained that there aren’t enough guards on duty to take them to the hospital even during emergencies. Women have had to sit cross legged in quiet corners while on their period for they wouldn’t have sanitary pads or even unused pieces of cloth to drape themselves with. Often, the police staff would give medicines to women who are complaining of health issues without even maintaining transparency about the drugs that are being injected into their bodies. And more often than not, these drugs are used as sedatives to ‘tranquilize’ the women. Worse still, they fear displacement from the jail to the asylum upon being pronounced ‘mentally ill,’ as Sori mentions. Despite having borne the brutalities on their bodies, these women have no right to express their anger lest they be declared ‘mentally ill’ and be taken to asylums, which are themselves in bad shape.

Further, the women prisoners are paid less as compared to even the abysmal pay of their male counterparts. They are paid Rs 10 a day for the work they execute, and the State’s rationale for denying them minimum wage lies in the fact that the State incurs the expense for their lodging and food and that the labour they perform is not geared towards public good, it is rather a punishment. However, these prisoners have only their right to liberty curtailed and not their right to live with dignity, in which case if the inmates are being brutalized to work without wage and secure working conditions, beaten to produce goods for their own prison upkeep – then these acts do amount to extraction of forced labour. Moreover, the prisons don’t even fulfill the basic dietary requirements, not even close to meeting minimum humanitarian standards – they are often served half a plate of food, which women with children are expected to share with their wards.

Uma pointed at the crude irony of having made special provisions for cells for ‘high profile’ criminals who may or may never get ‘caught.’ So naturalized are the stratifications along caste and class lines, that the hollow claim of respectability associated with class trumps the idea of a life of dignity for each human life. Justice, for those who cannot afford it, means only to be punished for fighting the injustices that they endure.

From Ek Aur Inquilab Aaya, a film directed by the historian Uma Chakravarti. She has been working on an extended project on women political prisoners in India, and this is one of the films that have already been released. Image credit: Public Service Broadcasting Trust. Source: https://scroll.in/reel/850967/an-urdu-poet-her-activist-niece-and-two-faces-of-rebellion-at-lucknows-farangi-mahal

Those After Me – Intergenerational Scars and Inherited Oppression

The treatment of children in the prison was a recurring theme at the event and was discussed at length in the hearing. Women prisoners spoke about the heavy price that the children who have been brought into this world in the prison cells have to pay – they are born in the shadows to remain in the dark. The children are mostly products of unwanted pregnancies accruing from rapes by the forces. The fact of such a pregnancy in itself is a traumatic reminder of the violence that the women and girls had to endure. Sori shared with us the story of a minor girl who was raped by the Armed forces in the forests and was later put in prison with charges of being a ‘Naxal.’

Owing to her own tender age, she took time to understand that she was carrying a baby in her womb. The horror of such a reality was enough to want her to flush the baby down the toilet, the moment she got the chance to, until another inmate stepped in and volunteered to raise the child in her own name. The fear of societal shame, stigma for having had a baby without marriage was too great for the woman to keep the baby, besides the fact that the baby itself was a marker of a memory she wished to forget. She refused to feed the baby her breast-milk and the rest of the inmates were pushed towards making ethical decisions on her behalf. Sori recounted how conflicted she felt in having to forcefully squeeze out the milk off of the biological mother, despite her resistance, only to keep the baby alive. She later appealed for counseling for such mothers – who are weighed down by the burden of a forced motherhood.

Prison inmates are always running the risk of encountering infection while giving birth in such un-healthy environments. Soni also mentioned how more often than not, when entire villages are combed in search operations, it is the pregnant women who are unable to run and hide and therefore, are most likely to be framed and put behind bars. Therefore, there is a good number of child births that take place within these jails, despite the environment being the least conducive for it. Their children are later denied the right to attend school, are only expected to stay with the mother until the age of five and are later expected to enter the world they have had no interaction with or exposure to. They come out completely disoriented with the only learning being the power balance of the jailer and the function of the whip. Where would these kids go, if the natal families or kins of the prisoner have broken ties with her? Should not the State bear responsibility in integrating their children with the outside world? Xavieramma from Kudankulam said that here is where the role of the political movements become important. With entire communities and families being invested in the fight against corporate land grabbing mafia, the kids always have a larger movement to fall back on. The women prisoners who belong to political movements are often greeted with slogans and chants upon their release, but it is the category of women prisoners not attached to political struggles who often don’t find themselves being accepted back in the society they had left for prison.

Body of a woman

Many of the speakers spoke – directly or indirectly—about the carefully crafted violence that the bodies of women — particularly those from marginalized backgrounds – have to face. Often, these women are from Adivasi, Dalit, and Muslim communities, and coming from places where the people are challenging the might of the State. Their bodies are often reduced to metaphors of war. But they are not only what the war writes on them, their bodies aren’t unmarked from before and then happen to get marked by violence. They are marked bodies who further get mutilated in and for their marked-ness. Soni Sori sharply articulated how it is the Adivasi, the Gonds, who are the resisting the State-corporate-Police nexus are the first to be pronounced Maoists as a self-justification for the State for every violation that they mete out on these ‘Maoists,’ thereon. Sori recounted the worst tortures that she and her inmates had to face. On the one hand their bodies were brutalized and on the other hand, they were shamed for sharing with the world their experiences of custodial violence. It is only when Sori upturned the Raipur jailer’s strategy to use shame as a weapon of silence, by staging a protest in which she refused to put on clothes if they were to anyway be snatched off her by the police forces – that the police was forced to concede to her appeals to stop the forced stripping.

Moving Forward

At what point the pen fell off my hands, I do not know. Was it when Anjum Zamrud Habib bemoaned the deafening silence of Indians on matters concerning Kashmir? Was it when one of the former inmates of Mirzapur jail shared her own disbelief of having survived in jail for five months on just an apple a day? Was it when Soni Sori recounted the screams of a minor child tormented by the baby in her womb, impregnated by the rape that one of the Army men had committed on her? Or when Soni Sori spoke of the of a fellow inmate, whose body was so badly brutalized that even she felt her wounds go cold?

Activist Arundhati Roy had once pointed out that all this is driven by the agenda to acquire land for industrialisation that Adivasis inhabit. She was backed in her claim by activist Himanshu Kumar, driven out of Bastar by state forces, who said that Kalluri once told a lawyer that he was doing what he did to get land. “Kalluri told this lawyer that he would shoot people if he had to, but he would not stop,” related Kumar. It is no surprise that cops like Kalluri are rewarded by political parties across the board, and encounter killings earn people promotions. In these prisoners of conscience, the state sees its enemies. Their activism, their expression of their political will is a direct threat to the legitimacy of the State, and so governments may change but their principled obligation to crush voices of resistance would not.

These accounts, as chilling as they were could not have been heard only to be forgotten. Uma Chakravarty, a member of the jury reminded us of our own responsibilities as listeners, as gatherers, as participants. In between spaces of resistance and suffering is an ethical responsibility that comes with feeling the pain of others. That the limits of our solidarity should not be that of mere consumption, feeling sorry, and a rendering present of our own gaze in the voices we heard. She reminded us that the struggle that lies ahead of us has a role for all of us, despite knowing well how the women who have served prison time are likely to remain more precarious than others in the room. A precise and poised Anjum Habib stated very matter of factly, “Jo bhi haq ki ladai ladega usko toh jail mein jaana padega! Toh jail se matt darein.”

Towards the end of the hearing Roma appealed to the audience in the room to not only limit its imagination to making demands for prison reform and rights. They are of course extremely important, but we should also extend the claim to saying as she does, “No woman should be in prison.” That the ultimate goal is to abolish prisons, that we are able to create a world in which we overcome the insecurities that engender its own necessity for a thriving prison complex. At the end of the program, it was decided that a detailed report would be worked on by the jury members, using the insights of the speakers.

Avantika Tewari is a political activist based in Delhi and a research scholar at JNU. Cover Image: Rajkumari, Kismati and others from Sonbhadra, Source: internet.

[…] SOURCE: https://www.groundxero.in/2019/01/25/women-in-resistance-women-in-prison/ […]