The “spontaneous” tendency of capitalism to produce “wealth at one pole and poverty at another” has been accelerated with a vengeance under neo-liberal capitalism. Post-reform India, since 1990s, is a classic example of this phenomenon. But under the Narendra Modi regime, inequality in India has reached obnoxious levels. 2018 saw historic levels of inequality in India (along with the rest of the world) according to several survey reports. A GroundXero recap of the ‘Year of Unprecedented Inequalities’.

Economic inequality as reflected in disparities of income and wealth distribution has received a good deal of attention from economist, policy makers and lately also sociologists. Within economics, the question of inequality has been studied in the context of economic growth. The proponents of ‘trickle down’ theory of development tell us, certain level of inequality is better to be accepted to accelerate economic growth. The benefits of increase in growth will trickle down to all sections of the society and lead to overall rise in income. The bigger is the size of the pie the better for all. When India ushered in neoliberal economic reforms (Liberalization-Privatization-Globalization ) during the early 1990s, under the leadership of Indian National Congress, the arguments were similar. Structural reforms, dictated by World Bank and IMF, it was argued will free the economy from the ‘fetters’ that were arresting its growth. The promise was job creation, inclusive growth and prosperity for all. But, some 25 years down the line, India today has the fourth highest number of billionaires, but also ranks 130th in Human Development Index (HDI) out of 188 countries; India is the third strongest economy in the world but also it stands in the 100th position on Global Hunger Index (GHI) out of 119 countries.

Narendra Modi came to power in 2014 backed by the Corporates, both domestic and global, as an architect of the ‘Gujarat model of development’, promising ‘Sabka Saath Sabka Vikaas’, which meant overall inclusive development for all. However, the reality on the ground and various studies and surveys, however, tells a different story. At the fag-end of his five years term it is crystal clear that like his other promises, this too was a ’Jumla’(false promise) to confound the people.

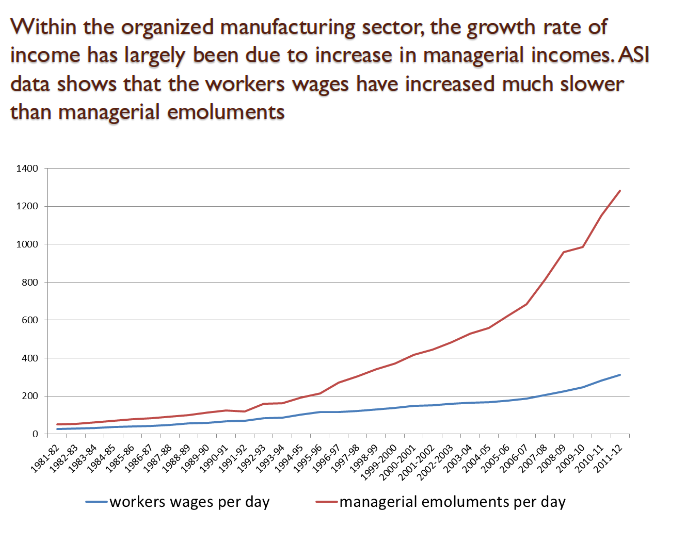

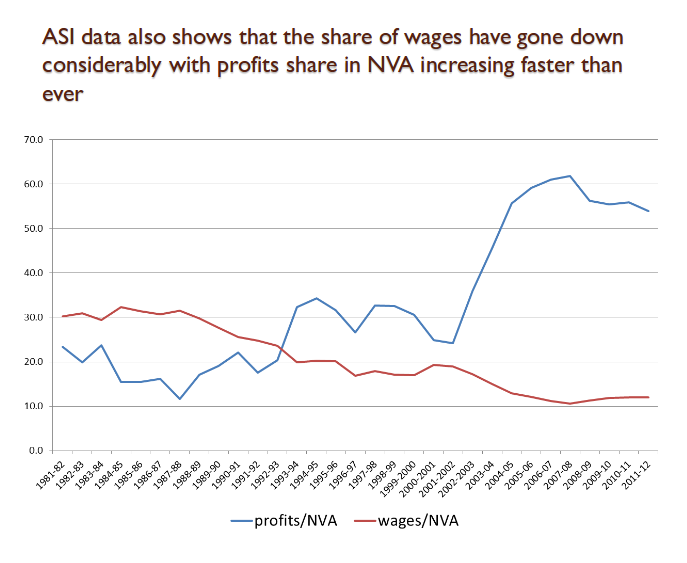

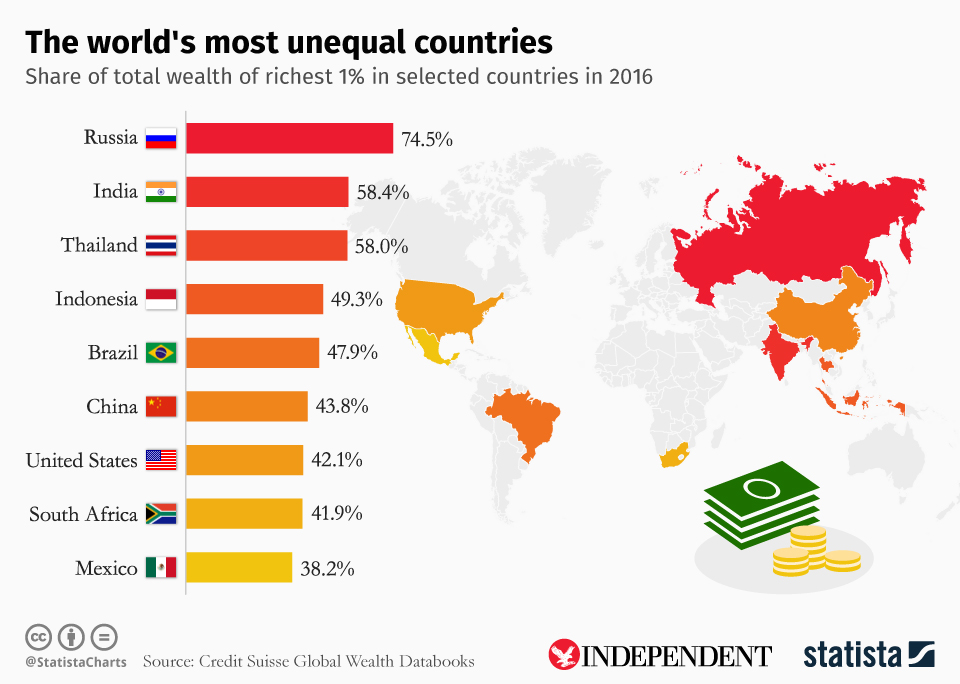

India is currently the fastest growing large economy. But this growth in GDP is also associated with shocking income disparities and overall deterioration in all human development indicators. India is experiencing the twin shocks of high levels of income inequality and a rapidly widening pace of such inequality.

Oxfam Survey report 2018

The annual Oxfam survey is keenly watched and is discussed in detail at the World Economic Forum annual meeting where rising income and gender inequality is among the key talking points for the world leaders. The 2018 report, released on 21 January, points out that the richest 1% in India has amassed 73% of the wealth generated in the country in 2017, presenting a shocking picture of rising income inequality. This year’s survey showed that the wealth of India’s richest 1% increased by over ₹20.9 trillion during 2017—an amount equivalent to the total budget of the central government in 2017-18. As per the survey report, 67 crore Indians comprising the population’s poorest half saw their wealth rise by just 1%.

Some shocking facts about inequality in India revealed by the report are summarized below :

1) India added 17 new billionaires in 2017, raising the number to 101. The number of Indian billionaires has increased from only 9 in 2000 to 101 in 2017.

2) Indian billionaires’ wealth increased by INR 4891 billion —from INR 15,778 billion to over INR 20,676 billion. INR 4891 billion is sufficient to finance 85 per cent of the all the states’ budgets on Health and Education.

3) In the last 12 months the wealth of this elite top 1 percent group increased by ₹20,913 billion. This amount is equivalent to total budget of the Central Government in 2017-18.

4) It would take 941 years for a minimum wage worker in rural India to earn what the top paid executive at a leading Indian garment company earns in a year. It would take around 17.5 days for the best paid executive at a top Indian garment company to earn what a minimum wage worker in rural India will earn in their lifetime (assuming 50 years at work).

5) It would cost around ₹326 million a year to ensure 14,764 minimum wage workers in rural India were paid a living wage. This is about half the amount paid out to wealth shareholders of a top Indian garment company.

6) India’s top 10% of population holds 73% of the wealth.

Credit Suisse’s India wealth report, 2018

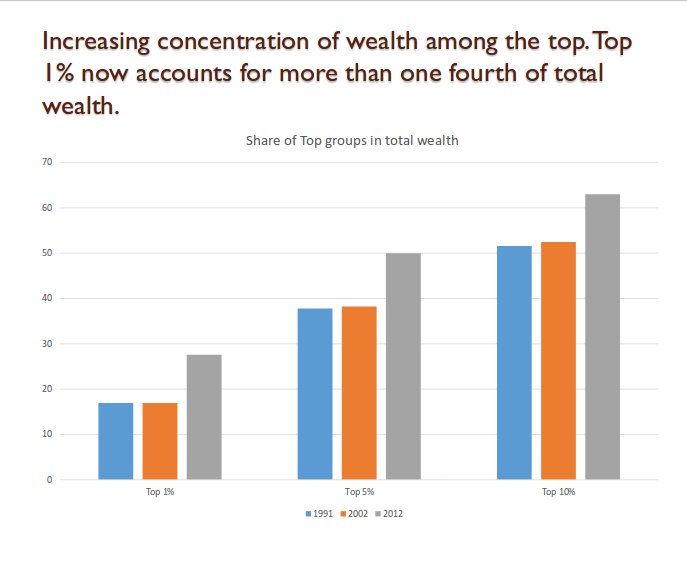

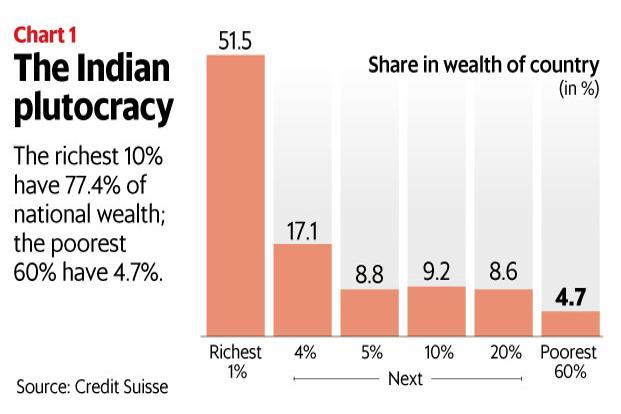

While wealth has been rising in India, not everyone has share in this growth. There is still considerable wealth poverty, says Credit Suisse’s India wealth report. The richest 10% of Indians own 77.4% of the country’s wealth, says Credit Suisse in their 2018 Global Wealth Report. The bottom 60%, the majority of the population, own 4.7% while the richest 1% own 51.5% of the country’s total wealth (see chart 1 below).

Strikingly, this enormous imbalance in wealth distribution – otherwise known as inequality – has worsened since the BJP government led by Narendra Modi came to power in 2014. In that year, the shares were reverse with the top 1% owning about 49% and the rest 99% owning 51% of the wealth, as per the 2014 Credit Suisse report.

The Gini coefficient is one way of measuring inequality, with a reading of 100% denoting perfect inequality and zero indicating perfect equality. According to Credit Suisse, the Gini wealth coefficient in India has gone up from 81.3% in 2013 to 85.4% this year, which shows inequality is rising.

World Inequality Report 2018

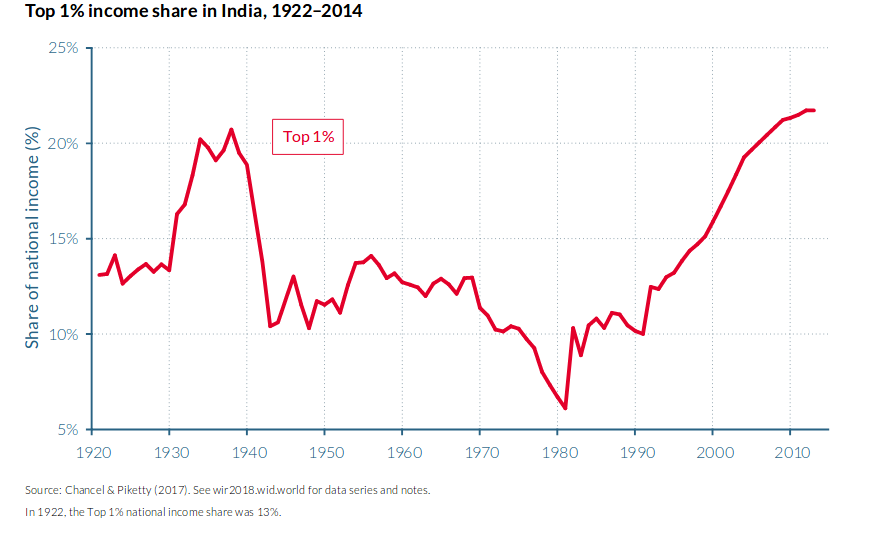

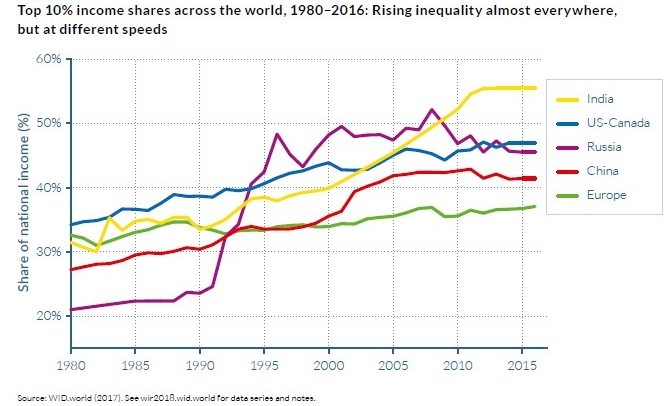

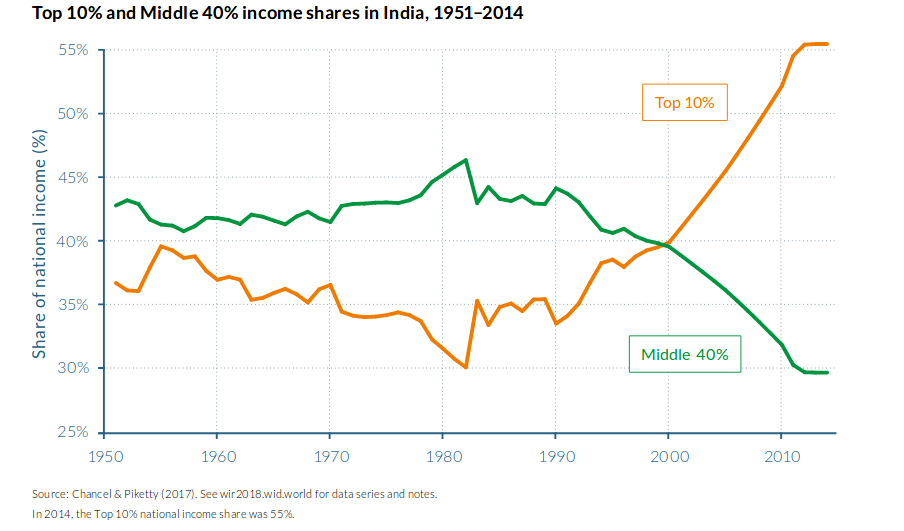

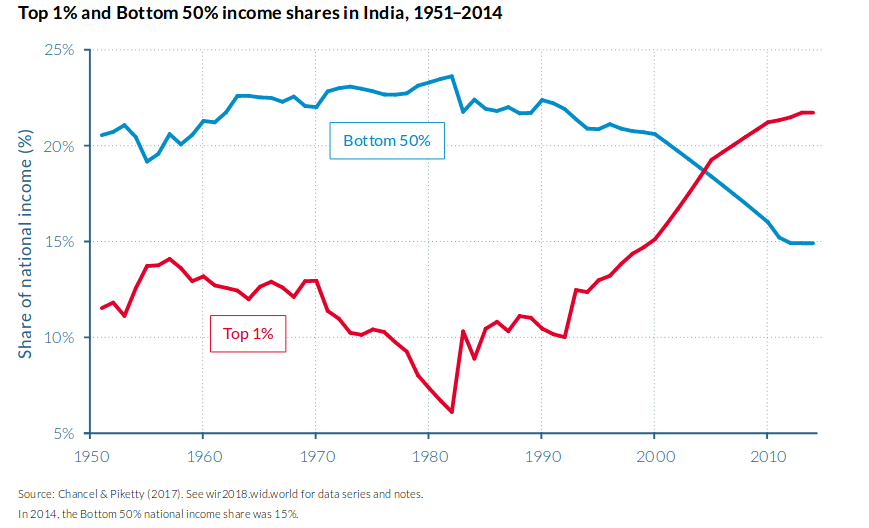

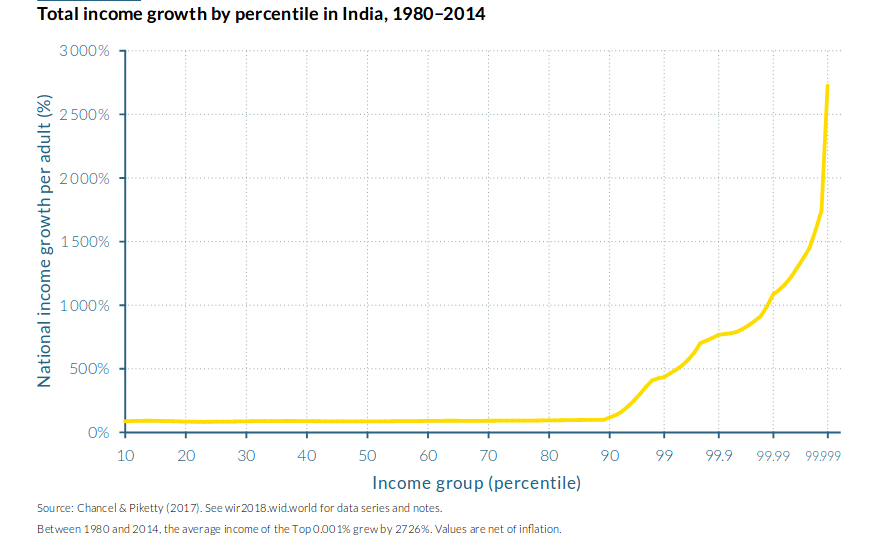

According to the World Inequality Report 2018, Inequality in India has risen substantially from the 1980s onwards, following profound transformations in the economy that centered on the implementation of deregulation and opening-up reforms. Since the beginning of deregulation policies in the 1980s, the top .01 per cent earners have captured more growth than all of those in the bottom 50 percent combined.

“The structural changes to the economy along with changes in tax regulation, appear to have had significant impact on income inequality in India since the 1980s. In 1983, the share of national income accruing to top earners was the lowest since tax records started in 1922: the top 1 per cent captured approximately 6 per cent of national income, the top 10 per cent earned 30 per cent of national income, the bottom 50 per cent earned approximately 24 per cent of national income and the middle 40 per cent just over 46 per cent, but by 1990, these shares had changed notably with the share of the top 10 per cent growing approximately 4 percentage points to 34 per cent from 1983, while the shares of the middle 40 per cent and bottom 50 per cent both fell by 2 percentage points to around 44 per cent and 22 per cent, respectively,” the report said.

The various estimates of inequality have been questioned by many economists like Montek Singh Ahluwalia, Jagdish Bhagwati, and Surjit Bhalla. In their opinion the methods used by those who find high and increasing inequality are problematic. Using proper methods, they argue, it can be shown that inequality in India is low to moderate and increasing slowly, if at all.

Data on income inequality can always be questioned. In India we have no income surveys. All we have are sample surveys relating to consumption expenditure. Firstly, from the distribution of consumption expenditure (based of NSS data), it is problematic to derive the distribution of income since we do not know how savings, which constitutes the difference between the two, are distributed. Secondly, the upper tail of the income/wealth distribution in India is inscrutable. Surveyors are never able to enter the houses and gated apartments in which the super rich and upper class live and ask them about their income or wealth. Even if some survey did manage to do so, there is no reason to expect that they will be told the truth. Therefore, all arguments on inequality based on such survey data are futile.

Also, income tax data does provide some information, but they cover a small proportion of the population and are notoriously prone to “understatements.” But no matter how one views the absolute figures of inequality, the trends revealed by these surveys can scarcely be questioned, since more or less the same method of estimation is employed across time. And this trend tells us that in India, as everywhere else in the world, the rich are getting richer and the share of the poor is drastically declining. And this decline has gathered more pace during the last five years under the Modi government.

Crony Billionaires and the political system

Men like Vijay Mallya, Nirav Modi are members of India’s expanding billionaire class, of whom there are now 119 members, according to Forbes magazine. Last year, the collective worth of all these billionaires amounted to a staggering $440bn. The amount of tax breaks and handouts given to the corporate sector and the massive amount of corporate debt written off by state-owned banks, while farmers kill themselves en masse because of paltry debts, is a result of corporate-state nexus which gave rise to this neo-liberal crony-billionaire class.

In 2014, within two months of the BJP government at the center, the RBI introduced a scheme called 5/25. This scheme allowed PSU banks to refinance and restructure the bad loans of many of the big corporates. The payment period for these bad loans was extended to 25 years from original maturities of 10 years or so. The direct beneficiaries of this new scheme are the billionaires like Gautam Adani, Mukesh Ambani and Anil Ambani.

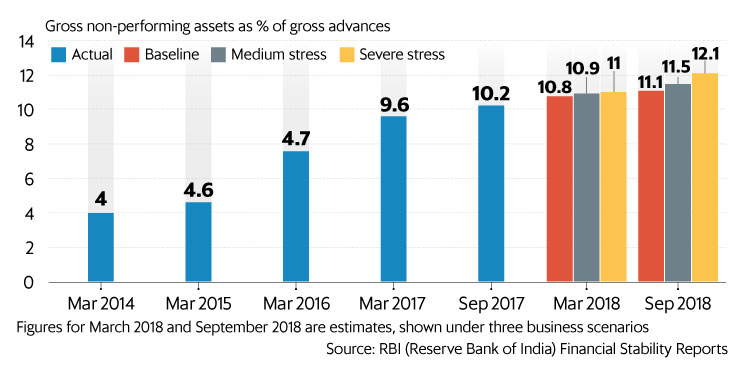

Vijay Mallya defrauded a public sector bank of ₹9,000 crore; Gautam Adani owes a debt of ₹72,000 crore. During the Modi regime there has been a huge fall in the ‘bad loan’ collection owed by corporates to banks. RBI report according to NDTV says, “In 2015-16, the second year of the present Modi government and the last year for which data is available, gross NPA nearly doubled to 7.5%.” At least 10 major corporate borrowings were written off. SBI alone waived off ₹7,000 crore owed by 63 big capitalist defaulters. In reply to an RTI filed by economist Prasenjit Bose, RBI admitted, “There were 9193 cases of Loans Frauds in the last 4 years (April 2014 to March 2018), involving an amount of ₹77521 crore”.

Latest data released by the RBI reveals that fraudsters have looted Indian banking institutions of ₹42,167 crores in 2017-18 alone. A majority – about 80% of all recorded frauds in 2017-18 – were large-value frauds, wherein each case involved an amount of ₹50 crore or more. These crony-billionaires had borrowed huge sums from state-backed banks and invested with gleeful abandon, in one of the largest deployments of private capital during recent times. But after the global financial crisis 2008, the tycoons’ hubris was exposed, leaving their businesses over-stretched and struggling to repay their debts. In 2017, 10 years on from the crisis, India’s banks were still left holding at least $150bn of bad assets.

India’s old system created fertile grounds for corruption, forcing citizens and businesses alike to pay myriad bribes for basic state services. But these humdrum problems were trivial compared with the grand scandals that emerged after the 2000s covering the rule of UPA and extending till now. Assets worth billions were gifted under the table to big tycoons by politicians and bureaucrats. Giant kickbacks helped businesses acquire land, bypass environmental rules and win infrastructure contracts. One estimate suggested that India’s 2014 election cost close to $5bn, a huge increase over the polls of the pre-liberalisation era. Political parties had to raise more money, to fight elections and fund the patronage that kept them in office. Election experts believe most of this money is brought in illegally from favoured business tycoons, in exchange for promised future favours.

We present below a few examples of how the political class has collaborated and helped in the amassing of huge wealth by some these crony-billionaires in the top 1 percent.

The spectacular rise of Vijay Shekhar Sharma, owner of Paytm

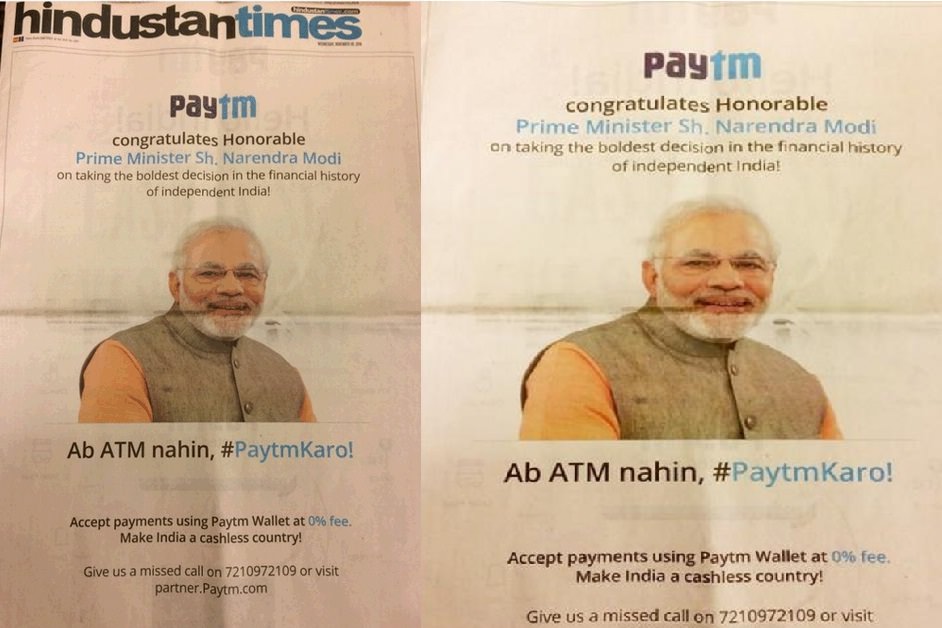

Son of a schoolteacher from a small city in north India, Vijay Shekhar Sharma founded fast-rising mobile wallet Paytm in 2011. Paytm went on to become one of the biggest beneficiaries of demonetisation. On 8 November 2016, Prime Minister Narendra Modi had demonetised all five hundred and one thousand rupee notes in an unscheduled televised address. That night, 85% of India’s cash in circulation ceased to be legal tender. The very next morning, Paytm took out front page newspaper advertisements congratulating the prime minister on the “boldest decision in the financial history of Independent India!”

The use of PM’s picture was deliberately done to create an impression that Modi, the Prime Minister, was endorsing the brand Paytm. This has never happened before. Many, including Delhi CM Kejriwal, described Modi’s presence in the advertisements not only objectionable but also suspect.

But the trick was done. The money deposited in Paytm mobile wallets had increased a 1000% in just one month. The company’s user base catapulted from 140 million in October of 2016 to 270 million in November of 2017. The company raised a massive USD 1.4 billion amount in May of 2017 from Japan’s Softbank, even as other consumer internet companies floundered for money in a depressed economy. The company’s valuation also more than doubled to USD 7 billion.

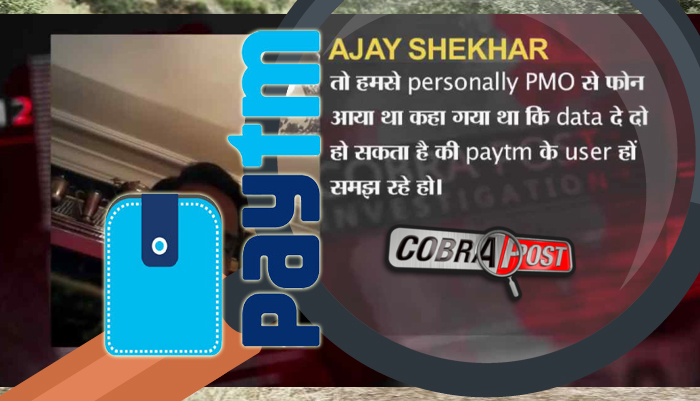

Eighteen months later, on May 25, 2018, in a grainy footage shot on a hidden camera, Ajay Sharma, brother of Vijay Shekar, appears to tell an undercover CobraPost journalist that Paytm had very close relations with Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), the parent organisation of the ruling Bharatiya Janta Party. Ajay also appears to say that the “RSS is in our blood”, and that Paytm gave advertisements in the Organiser, the RSS’s mouthpiece, as a way to fund the parent organisation. These two viral videos point to Paytm’s cosy relationship with the ruling party, and cement his reputation as the most recent crony-corporate — in an economy ruled by politically-connected oligarchs – to get crucial policy decisions to swing their way.

Vijay Shekhar Sharma is hardly alone

The phenomenal rise of Gautam Adani has happened during the time of the Gujarat Model of growth propounded by Narendra Modi. In the 10 year period from 2002 to 2012, Adani rose from an ordinary medium term businessman to become India’s 21st richest man according to the Fortune magazine. The relationship of corporate-state nexus is further strengthened by the fact that Modi uses the Adani’s plane to travel all over India during elections. Adani cancelled the sponsorship of a Wharton India Economic Forum event last year after it dropped a live video address by Modi.

Oil and gas tycoon Mukesh Ambani added $9.3 billion in the year 2018 alone, amid the continuing success of his Reliance Jio broadband telecom service. Modi Government’s promotion of Jio to gain domestic market share by denying 4G spectrum licence to public sector telecom company VSNL is well known. This rise of crony capitalists is intimately connected with gutting of public sector enterprises like VSNL.

Gutting of HAL

Recently, Hindustan Aeronautics Ltd (HAL), in order to meet the monthly salary bill of ₹358 crore, and to keep the production lines running (which requires ₹1,300-1,400 crore per month), took a bank loan of ₹781 crore. This was the first time in history that HAL had to take such a loan. The Indian Air Force (IAF) owes HAL dues of ₹20,000 crore (₹200 billion), says the Chairman, R Madhavan. HAL, traditionally a cash-rich firm, has steadily transferred ₹11,024 crore of its cash reserves to the government. In addition, over the past five years, HAL paid the government dividend and taxes worth ₹4,631 crore.

In a press conference held on 10th January, employees of HAL had accused the Modi government of a systematic conspiracy to “bleed and shut” down the public sector aerospace firm. The Modi Government is drying the company of new orders. HAL, which was initially the most preferred ‘offshore’ partner for Rafale deal, was dropped out in favour of Anil Ambani’s newly created defence firm. The sinister design is to push HAL into losses and ultimately sell it off to his favoured cronies.

Even the much publicised Fasal Bima Yojna, launched by Narendra Modi to insure farmers against crop damage caused by drought or flood, was a scheme designed to ‘transfer’ millions of Government (public) money to private insurance companies. “The Pradhanmantri Fasal Bima Yojana is a bigger scam than even the Rafale scam. Selected corporates like Reliance, Essar have been given the task of providing crop insurance,” said journalist P. Sainath.

Giving an example of Maharashtra, Sainath said: “Some 2.80 lakh farmers sowed soya in their farms. In a district, the farmers paid a premium of Rs 19.2 crore, the state government and the central governments paid Rs 77 crore each, amounting to a total of Rs 173 crore, which was paid to Reliance insurance. The entire crop failed and the insurance company paid out the claims. Reliance paid Rs 30 crore in one district, giving it a total net profit of Rs 143 crore without investing a single rupee. Now multiply this amount to each of the districts it has been entrusted,” he said.

The list of such loots of public money can go on and on. Many of those who backed India’s economic reforms had hoped that a dismantling of license-permit raj in favour of a more free-market economy would lead to more honest and transparent government decisions. Instead, crony capitalism captured almost every aspect of national life. Billions of dollars were siphoned away by a shadowy alliance of colluding politicians and business tycoons. India’s old system of retail corruption has become wholesale.

Conclusion

The redistribution of this fraudulently acquired wealth from the top 1-10 percent to the lowest 20 percent surviving on less than 10,000 per month is the only way to control this obnoxious inequality plaguing the country. This will need, in the least, introduction of wealth tax, increase in income tax rates for the rich, stopping tax concessions for corporates, provision of quality education and health services to all by the State, less dependence on indirect tax for revenue collection, fair wage for all, distribution of land among the landless peasantry, ensuring the right of Adivasis on forest land and its produce, government funding of elections, holding PSU bank managements accountable for siphoning of public money by the corporate, etc.

This means abandoning the path of neo-liberalism. But this is not just a matter of policy choice for the Indian rulers that it can be given up at will. Neo-liberalism corresponds to the current stage of capitalism in which international finance capital’s hegemony holds sway. Overcoming it will need a radical transformation of the polity and economy, which the current ruling class because of its very nature is incapable of doing. The Gilet Jaunes (Yellow Vests) in France showed us a glimpse of what to expect, unless some of the above peaceful methods are pursued sincerely by the rulers of this country.

Feature image courtesy Johnny Miller.

Wonderful