In order to decide the meaning of ‘Economic Backwardness’, Modi Government set up no Commission, or undertake any comprehensive study across the country, unlike what the apex court had stipulated in the Indra Sawhney case (1992). But the present arbitrariness of a blanket 8 lakh per annum slab for economic backwardness for the ‘forward classes’ is more than just side-stepping standard procedures or a few court orders. What this Amendment represents is the current regime’s attempt of by-passing, and erasing, an entire history of legislative struggles around the idea of ‘backwardness’, reservations and ‘equal opportunities’. What it also signifies is a deep Constitutional crisis between the ideas of ‘Equality for All’ and ‘Protection for Some’. In this concluding part of a two-part coverage, we trace the history of this conflict that is essentially as old as the Constitution itself. Siddhartha Dasgupta writes. For the first part, click here.

‘Backwardness’ and the History of Legislative battles over Reservations

The Legislative history of reservations in India has been fraught with the tension between ‘Equal Opportunity for All’ and ‘Special Protections for Some’ – and legality around the notion of ‘backwardness’ has been the fulcrum on which this battle has always been fought. The key issue is regarding the proper legally acceptable definition of ‘backwardness’. Article 16(4) of the Constitution says, “Nothing in this article shall prevent the State from making any provision for the reservation of appointments or posts in favor of any backward class of citizens…”. It does not explain what ‘backward class’ really means. Kaka Kalelkar Commission, the first Commission set up to decide ‘backwardness’, listed out 2,399 castes as ‘socially and educationally backward’ (for short ‘SEBCs’) on the basis of an 11-point Social, Educational and Economic criteria. The Second Backward Classes Commission (aka Mandal Commission), in its very first letter dated 25th April 1979, addressed to all the Ministries and Departments of the Central Government, prescribed a test for determining ‘socially and educationally backward classes’. There is however no such expression as “Socially and Educationally Backward Classes” in Article 16(4) – a clause that has been in the Constitution from its very initial days. In the Indra Sawhney case, the SC noted that “This expression [SECB] is used as an explanatory one to the words ‘backward class’ occurring in Article 16(4).”

On the other hand however, Article 15(4), a later addition to the Constitution, does contain this phrase. And unlike 16(4), 15(4) was inserted in the Constitution not initially, but only after the Constitution (First Amendment) Act of 1951. The inclusion of Clause 4 in Article 15 through the Amendment, was a historic event, and captures the essence of the Constitutional crisis mentioned in the introduction.

The curious case of Article 15(4)

The Government of Tamil Nadu had issued in 1927 what was popularly termed as the ‘Communal G.O.’ making compartmental reservation of posts for various communities. In 1950 one Smt. Champakam Dorairajan who intended to join the Medical College, filed a Writ Petition for restraining the State of Madras from enforcing the ‘Communal G.O.’ on the ground that the G.O. was in violation of the fundamental rights guaranteed under Articles 15(1) and 29(2) – No citizen shall be denied admission into any educational institution maintained by the State or receiving aid out of State funds on grounds only of religion, race, caste, language or any of them.

Today when Narendra Modi redefines ‘backwardness’ as also ‘economic backwardness’, he is making instrumental use of this same crisis of the definition of ‘backwardness’ that has been intrinsic to our legislative history since the very beginning, dating back to the days of drafting of the Constitution.

Champakam Dorairajan won the case. The State of Madras filed an appeal in the Supreme Court. A seven-Judges SC Bench dismissed the appeal holding “the Communal G.O. … inconsistent with the provisions of Article 29(2)”. This judgment and the crisis it created for the very foundations of special protections as enshrined in the Constitution, necessitated the introduction of the Constitution (First Amendment) Bill, whereby Clause (4) was inserted to Article 15 – Nothing in this article or in clause (2) of Article 29 shall prevent the State from making any special provision for the advancement of any socially and educationally backward classes of citizens or for the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes. Thus, while the words “backward class of citizens” occurring in Article 16(4) are neither defined nor explained in the Constitution, the same words occurring in Article 15(4) are followed by a qualifying phrase: “Socially and Educationally”.

Today when Narendra Modi redefines ‘backwardness’ as also ‘economic backwardness’, he is making instrumental use of this same crisis of the definition of ‘backwardness’ that has been intrinsic to our legislative history since the very beginning, dating back to the days of drafting of the Constitution.

This was never a ‘new’ crisis

Article 16(4) (then Article 10(3)) in the initial draft of the Constitution did not even contain the qualifying word ‘backward’ preceding the phrase ‘class of citizens’, and had to be later inserted because of the crusade led by Dr. BR Ambedkar as the Chairman of the Drafting Committee. “… we have quite a massive opinion which insists that although theoretically it is good to have the principle that there shall be equality of opportunity, there must at the same time be a provision made for the entry of certain communities which have so far been outside the administration,” he argued. It was this demand which was mainly responsible for the incorporation of Clause (4) in Article 16. Ever since, it became necessary for the Courts to interpret and explain the words ‘backward class’, leading to a plethora of decisions and explanations, including several engaging debates on ‘class’ and ‘caste’ in this country – their divergences and their convergences. An archive of these decisions and interpretations, till 1992 at least, can be found in the judgment of the Indra Sawhney case.

A look at the Constituent Assembly debates shows how intrinsic this conflict between ‘Equality’ and ‘Reservation’ was to the construction of the nation’s legislative foundations itself, and how central a role the term ‘backward class’ played in this tension. During the discussions on draft Article 10 (today’s Article 16), while a significant section of the lawmakers went on a vicious battle against Dr. Ambedkar for his insistence on the adjective ‘backward’, there are extensive accounts of members belonging to the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes expressing serious apprehension on the other hand that the expression ‘backward’ was not precise. They were worried that large sections of people who did not belong to the Scheduled Castes or the Scheduled Tribes were likely to claim the benefit of reservation at the expense of the truly backward classes. Many wanted the expression ‘backward’ to be applied only to the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes. And none other than Dr. Ambedkar recognised the crisis. “…The Drafting Committee had to produce a formula which would reconcile these three points of views, firstly, that there shall be equality of opportunity, secondly that there shall be reservations in favour of certain communities which have not so far had a ‘proper look-in’ so to say into the administration…,” he said.

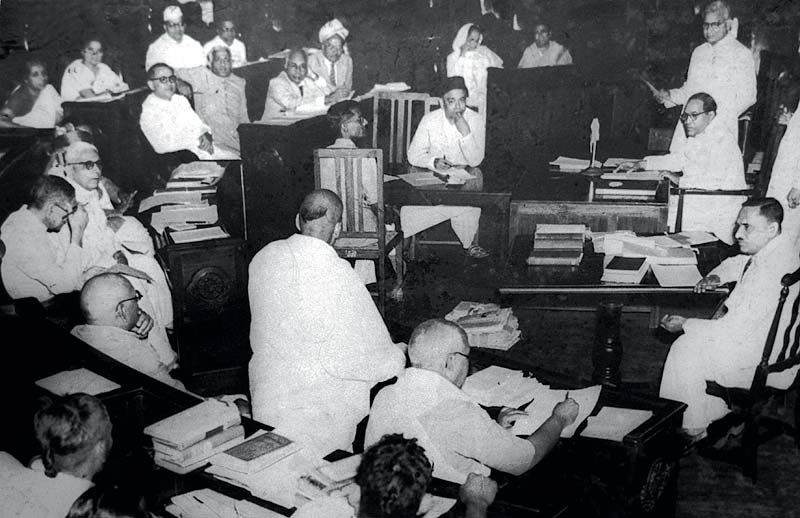

A Constituent Assembly of India meeting. B.R. Ambedkar can be seen seated top-right. Source: Wikimedia Commons.

Not just Caste, but also Religion

This same conflict took place between the the idea of ‘Secularism’ and special protections for minority religions in the country. Perhaps the most telling admission of the crisis of an ‘Indian secularism’ is Loknath Misra’s comment in the Constituent Assembly debate on December 6, 1948. “…I thought that the secular State of partitioned India was the maximum of generosity of a Hindu dominated territory for its non-Hindu population. I did not, of course, know what exactly this secularism meant and how far the State intends to cover the life and manners of our people,” he said. Vice president of the drafting committee, HC Mookherjee asked, “Are we really honest when we say that we are seeking to establish a secular state? If your idea is to have a secular state it follows inevitably that we cannot afford to recognise minorities based upon religion.”

On November 15, 1949, Professor K.T. Shah wanted to include the words “secular, federal, socialist” in Article 1(1) of the Constitution, the article that now reads, “India, that is Bharat, shall be a Union of States”. Ambedkar, however, rejected this saying “What should be the policy of the State, how the Society should be organised in its social and economic side are matters which must be decided by the people themselves according to time and circumstances. It cannot be laid down in the Constitution itself because that is destroying democracy altogether,….It is perfectly possible today for the majority people to hold that the socialist organisation of society is better than the capitalist organisation of society. But it would be perfectly possible for thinking people to devise some other form of social organisation which might be better than the socialist organisation of today or of tomorrow. I do not see therefore why the Constitution should tie down the people to live in a particular form and not leave it to the people to decide it for themselves.”

Given how much our society and politics has gone down the path of religious majoritarianism in the recent years, if one were to bet, the next unanimous legislative attacks would possibly be on Article 30, using the rationale of ‘secularism’.

Prof. Shah’s amendment was rejected by the Assembly. Instead of writing ‘Secularism’ into the document, Articles 25, 26, 27 were adopted (free profession, practice and propagation of religion; to establish and maintain institutions for religious and charitable purposes; protection from religious taxes and religious instruction in state-funded institutions; permission of educational institutions of choice to linguistic and religious minorities; etc). Articles 29 and 30 were simultaneously added, giving special protection for the minorities (Protection of interests of minorities; Right of minorities to establish and administer educational institutions). Many historians and Constitution experts have argued that the reluctance of democrat lawmakers like Dr. Ambedkar in incorporating the word ‘Secular’ was their apprehension that the limits of the ‘generosity’ of the Hindu majoritarian secularists, as is apparent from Loknath Misra’s comments, would work against the idea of ‘Special Protection’ for the minority religions. They were anxious that the majoritarians would in that case cite the Constitution itself (specifically, the mention of the term ‘Secular’ in it) to push their agenda against religious minorities and the special protections meant for them.

As a cruel irony of history, the term ‘secular’ was to be finally added to the Constitution by one of the most despotic leaders the country has seen – Smt. Indira Gandhi. ‘Secular’ made it to the Preamble through the 42nd Amendment Act, 1976, at the time when the country’s democracy was reeling under the Emergency. After the Emergency, the 44th Amendment by the Janata government undid most of the substantial damage done by the 42nd Amendment. But it, too, chose to preserve the addition of the words “socialist” and “secular” to the Preamble.

Exactly 42 years after Mr. Misra made those comments about his understanding of ‘Securalism’, this nation witnessed the official demolition of the idea, on December 6, 1992. It is interesting that during tabling of the 124th Amendment Bill in the Lok Sabha, Arun Jaitley did cite the inclusion of “Secular” in the Constitution during the Emergency years, hinting that reservation for “Economically backward” upper castes was in the same ‘secular’ spirit of equal opportunity for all. Given how much our society and politics has gone down the path of religious majoritarianism in the recent years, if one were to bet, the next unanimous legislative attacks would possibly be on Article 30, using the rationale of ‘secularism’.

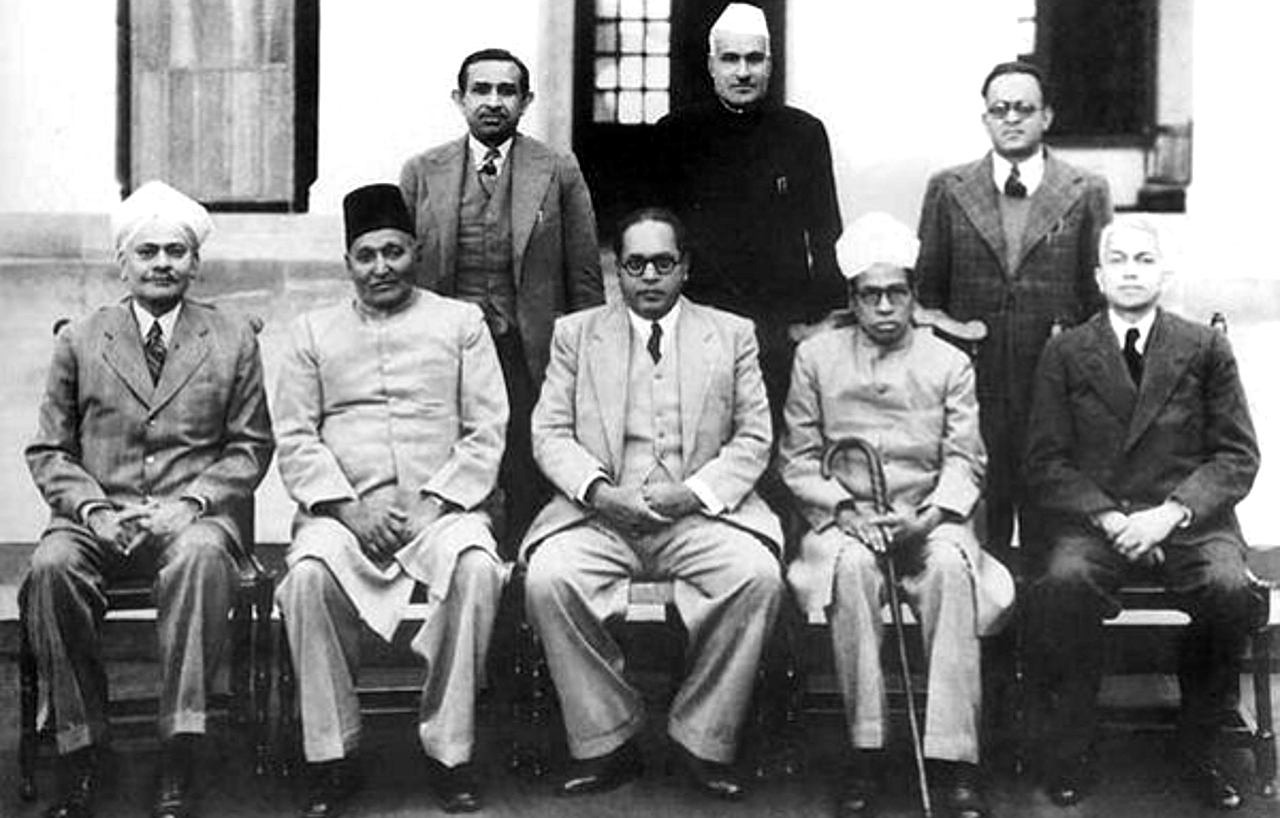

Dr. BR Ambedkar, chairman of the Drafting Committee, presenting the final draft of the Indian Constitution to Dr Rajendra Prasad on 25 November, 1949.

Back to the crisis around ‘Backwardness’

Though Dr. Ambedkar said at one point during the Constituent Assembly debates, “what are called backward classes are…nothing but a collection of certain castes,” but at other points he also recognized the complexities of reaching a proper legally objective definition, and the inevitability of such complexities. While answering criticisms regarding the qualifying word ‘backward’, he said: “I am not prepared to say that this Constitution will not give rise to questions which will involve legal interpretation or judicial interpretation. In fact, I would like to ask Mr. Krishanamachari if he can point out to me any instance of any Constitution in the world which has not been a paradise for lawyers. I would particularly ask him to refer to the vast storehouse of law reports with regard to the Constitution of the United States, Canada and other countries. I am therefore not ashamed at all if this Constitution hereafter for purposes of interpretation is required to be taken to the Federal Court. That is the fate of every Constitution and every Drafting Committee. I shall therefore not labour that point at all.”

At the same time however, he warned the Assembly of the dangers of ‘reservation for (essentially) all’ in the name of ‘equal opportunity for all’, when he said, “I am sure they will agree that unless you use some such qualifying phrase as “backward”, the exception made in favour of reservation will ultimately eat up the rule altogether.” (Constituent Assemble Debates, Volume VII Pages 700-703). He knew that awarding reservation to a group of people can only come at the cost of taking it away from another. “Every Hindu has a caste – he is either a Brahmin or a Mahratta or a Kundby or a Kumbhar or a carpenter. There is no Hindu – that is the fundamental proposition – who has not a caste. Consequently, if you make a reservation in favour of what are called backward classes which are nothing else but a collection of certain castes, those who are excluded are persons who belong to certain castes. Therefore, in the circumstances of this country, it is impossible to avoid reservation without excluding some people who have got a caste,” he said in his speech during the first Amendment to the Constitution.

In conclusion

BR Ambedkar was relentless in his battle for defending the legal recognition of ‘social backwardness’, and it was not an easy fight. Not just because of the opposition he faced from his upper caste colleagues, but also because it is a genuinely hard legal-philosophical fight to reconcile the two apparently antagonistic principles of ‘Equality for All’ and ‘Protection for Some’. The reason he could carry out the battle with such sharpness was because he was backed by, and came from a larger social movement across the country, fighting to eradicate an institution such as caste. He was representing not himself, or his own caste community, or his political party, but an entire spectrum of caste oppressed people’s resistance. If we are to give ourselves any chance of fighting a similar battle on the question of ‘economic backwardness’ in the Legislature or the Courts, we need lawmakers who, like Dr. Ambedkar, are thrown up by social political movements and can genuinely represent entire spectra of the street resistance against economic backwardness and economic inequality, going beyond themselves, or their party interests, or their own caste-class interests.

It is shameful that a Government can claim to have provided economic reservation for essentially the entire ‘upper caste’ middle class, albeit purely at the level of mere pen and paper, while shooting bullets at the poorest of its people demanding mere minimum wages – on the very same day!

Perhaps today’s debate around ‘economic backwardness’ and reservations on such a basis, would have been much more meaningful if there was a history of lawmakers in this country sweating over the issue of economic backwardness, with the same sincerity that Dr. Ambedkar pursued when it came to social backwardness. Perhaps it would have been much more easier to see through the Modi Government’s veil of lies around the crucial issue of economic backwardness, if the country’s legislative history had taken up the debate around class struggle with the kind of fervour and engagement that it deserves. It is unfortunate for the people of this land, that Governments that openly protect those who steal thousands of crores of public money and flee to foreign lands, get to also take moral electoral high ground on issues such as ‘economic backwardness’, amending the Constitution of the land in just a matter of 3 days. It is shameful that a Government can claim to have provided economic reservation for essentially the entire ‘upper caste’ middle class, albeit purely at the level of mere pen and paper, while shooting bullets at the poorest of its people demanding mere minimum wages – on the very same day!

Social Justice and Empowerment Minister Thaawarchand Gehlot and other BJP MPs after Lok Sabha passed the 10 per cent quota bill . Source: PTI

It is one thing to call out the lies of this Government, or its predecessor Government, or the regional satrap parties, it is one thing to panic over a handful of people destroying a Constitution that belongs to a billion and enshrines the history of serious labour and sweat by sincere lawmakers like Dr. Ambedkar (and we must do all of that!), but we ought to recognise where the traps are. Otherwise tomorrow it is possible that just like the word “Secular”, the word “Reservation” also loses its final traces of meaning while still decorating the text of the Constitution as a mere ornament, with people like Arun Jaitley whitewashing the scandal by claiming how “[Economic reservations] won’t disturb the already existing quota system, the bill is to provide economic justice”. Repeating Dr. Ambedkar one last time, “the exception made in favour of reservation will ultimately eat up the rule altogether.”

The author is a freelance journalist and a political worker. The feature image is a group photo of the Constitution Drafting Committee.