Rajveer Kaur, an MPhil student at the Department of Punjabi at Delhi University, along with her friends and comrades at bSCEM (Bhagat Singh Chhatra Ekta Manch), a student organization based in Delhi and the surrounding area, had brought out a wall-magazine with articles on Bhagat Singh and the poems of Paash, the left-revolutionary Punjabi poet. The HoD of the department, Dr. Jaspal Kaur, tore it to pieces. A seemingly trivial act, this incident gave birth to an interesting series of events on campus, which bring onto the fore multiple questions about gender, democratic spaces within the university campuses, alternative media cultures, Hindi-English domination inside DU, and the ways in which these things are intertwined. Nandini Dhar writes.

A wall-magazine is a strange form. It is cheap, invariably. All one needs is a sheet of paper to begin with, and a few hands to do the writing and drawing to complete it. A wall-magazine, because it is cheap, is almost always more democratic than any other form of media that we can think of. Part of its inherent democracy lies in the fact that a wall-magazine never lasts long. A perfect embodiment of ephemerality, the wall-magazine has nonetheless played an extremely significant role in the history of India’s radical and counter-cultural youth and student movements. There is a history of the strange intersection between political mobilizations and ephemeral literary-artistic forms which has yet to be written.

For many of us, a wall-magazine was one of the first platforms to write, vent, draw or doodle on. For many of us, the bringing out of a wall-magazine was one of the first collective endeavours which provided opportunities to learn and understand the stakes of collective editorial work. For many of us, wall-magazines were a kind of cultural artefact which made us realize, no progressive political-cultural work is neutral or completely risk-free. Yes, for many of us, attempts to paste a wall-magazine onto a college or university wall was also the first occasion to get beaten up or maligned by the powers that be. For many of us, seeing the wall-magazine we spent many sleepless nights to create get torn down by the authorities – college administrations, members of “mainstream” student organizations, professors who believed students should only come to college to “study hard” and pass exams – was also the first lesson in political pain, in cultural loss. In other words, what I am trying to say here is simple. Wall-magazines have existed within radical and alternative youth subcultures as a form of autonomous and independent mode of cultural production, which taught many of us the meaning and value of alternative media during times when we were not even aware that such a media could exist.

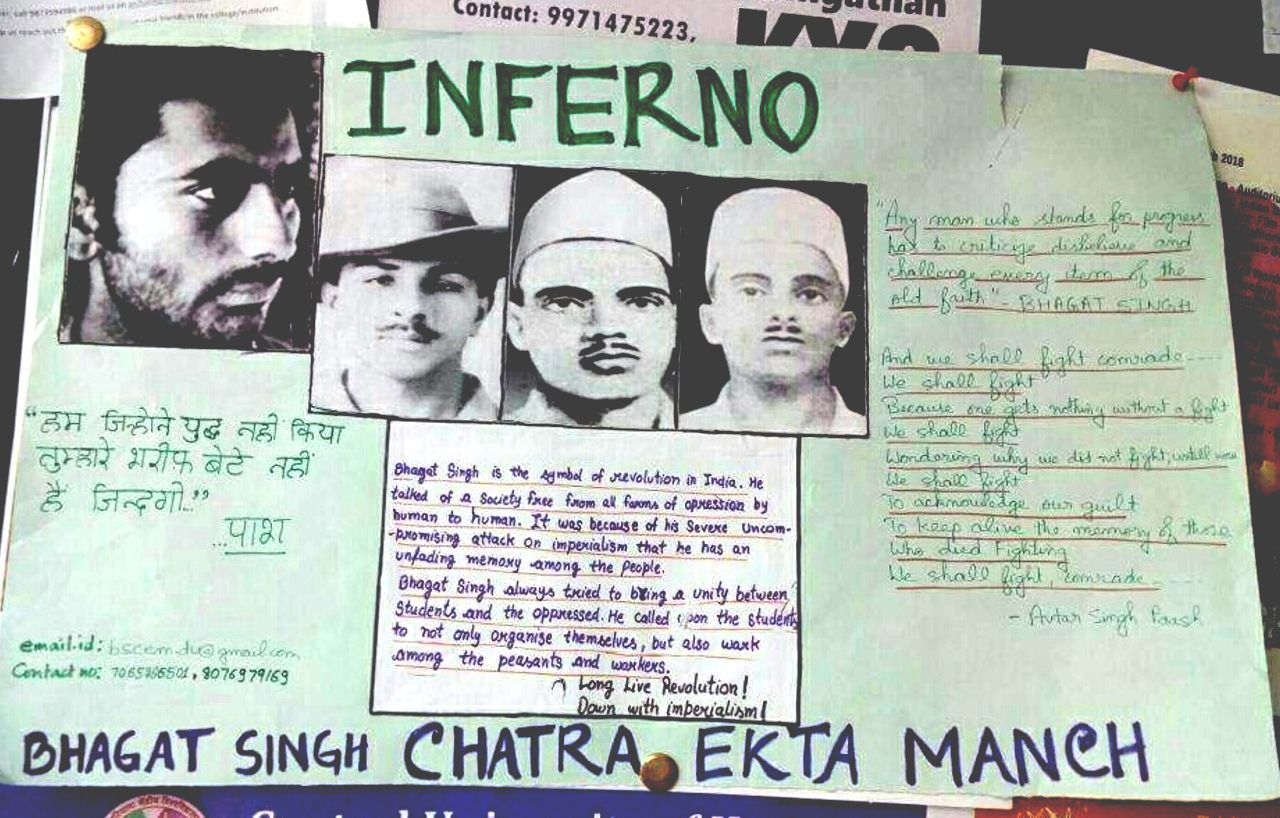

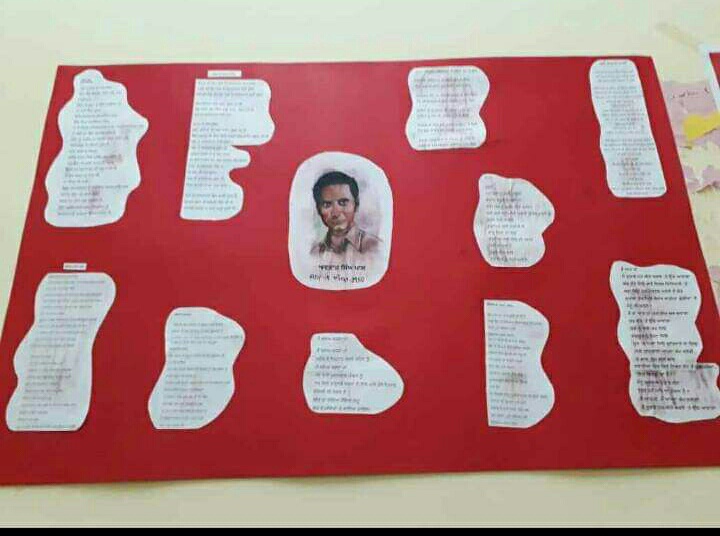

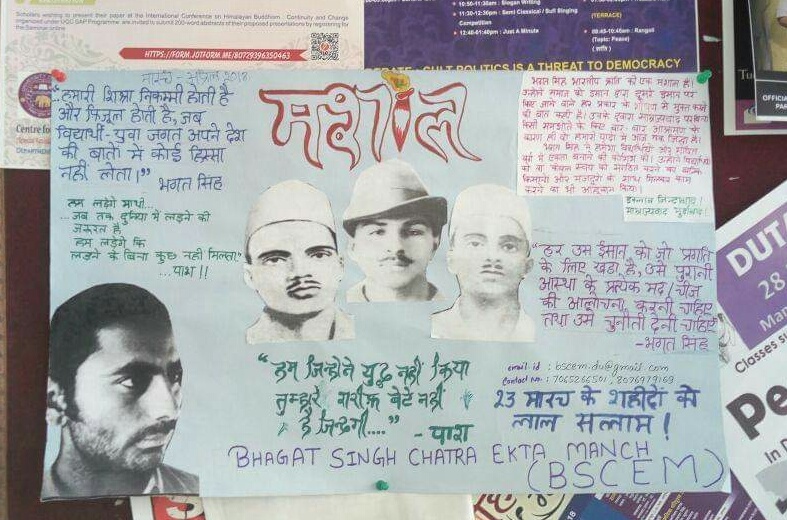

It is hardly surprising, then, that Rajveer Kaur, an MPhil student at the Department of Punjabi at Delhi University, along with her friends and comrades at bSCEM (Bhagat Singh Chhatra Ekta Manch), a student organization based in Delhi and the surrounding area, brought out a wall-magazine with articles on Bhagat Singh and the poems of Pash, the left-revolutionary Punjabi poet. Nor is it surprising that Rajveer, along with her friends and comrades, pasted the wall-magazine on the wall and the notice-board of the department. This is, after all, as I have pointed out earlier, an old strategy within radical and leftist student movements, through which students claim spaces within educational institutions.

For many of us, wall-magazines were a kind of cultural artefact which made us realize, no progressive political-cultural work is neutral or completely risk-free. Yes, for many of us, attempts to paste a wall-magazine onto a college or university wall was also the first occasion to get beaten up or maligned by the powers that be.

Rajveer happens to be an active member and President of bSCEM. According to her, bSCEM publishes wall magazines in four languages every month – Hindi, English, Urdu and Punjabi. In Hindi, Urdu, and Punjabi, the magazine is called Mashaal. In English, Inferno. Normally, these magazines act as spaces for students to comment upon current events and are put up in places such as the University Central library, walls and notice-boards of different departments and faculties within the university, and hostel canteens.

To those of us who are familiar with the everyday organizational methods of leftist, radical and/or progressive student movements and organizations, there is hardly anything new in this method. Yet soon after Rajveer put up the wall-magazine on the department wall, the Head of the Department (HoD) of the Department of Punjabi, Dr. Jaspal Kaur, tore it into pieces. Rajveer herself was summoned to Dr. Kaur’s office, and was told, if any such wall-magazine was put up again, she would be thrown out from the department and the university.

Just in the same way that one can place Rajveer’s actions in the context of a larger history of the strategies that have often been adopted by left and democratic student movements in this country and elsewhere, Dr. Kaur’s actions, too, can be put in a larger context of the reactions such strategies often elicit amongst professors and administrators. There is, of course, the tight-lipped professorial reaction to anything remotely political that students do, and that takes students out of the classroom space. I remember such professors from my own college and university days. The ones who believed students should be “apolitical.” The ones who would do something like what Dr. Kaur had done. And it is true, a lot of them did those things without having a specific political agenda in mind. In a strange kind of a way, many of the women’s colleges in India still reside within this space of death-like “apolitical” academic efficiency. In other words, there is a long tradition and culture of assault on the cultures of youth-led independent and alternative media that are inbuilt to the structure of our educational institutions.

But in the context of the present, one also needs to see the treatment meted out to Rajveer as far more complicated than that of a reaction of a tight-lipped professor who believes in the philosophy of an “apolitical” campus. Instead, Dr. Kaur’s actions need to be seen as examples of the ways in which, within this nation, the spaces of democratic discussion and dissent are shrinking under the current political regime. They are shrinking in accordance with a specific brand of right-wing Hindutva politics, which aims at erasing and invisibilizing any voices and opinions which can even be remotely described as democratic, egalitarian, anti-casteist, pro-feminist and pro-leftist. Yes, there is a way in which such politically motivated authoritative strategies bank upon the philosophy of “apolitical” professorial strictness. There does seem to be an unholy alliance of the two. Yet the current atmosphere of attack on any forms of speech that does not tow the official, government-sponsored line, goes far beyond the so-called apolitical culture of authoritarian professorialism.

In other words, seemingly trivial as it is, the threat of expulsion directed at Rajveer needs to be seen as the inevitable outcome of such shrinking of critical spaces within the universities and other crucial institutions of the nation. Rajveer’s story needs to be placed within the same continuum as the increasing repression of dissenting students at universities such as JNU and HCU, and within a larger context of increasing violence against women, dalits and minorities within the nation.

According to Rajveer, there is a patriarchal and “anti-woman” environment within the Punjabi department. For example, Dr. Kaur, as the HoD of the department, has a history of saying to the women students applying for PhD, “Tum PhD kar ke kya karogi, Punjab chali jao aur shaadi karo” (What will you do with a PhD, go back to Punjab and get married). On top of that, Rajveer continued, Dr. Kaur has habitually commented on the personal relationships the women students in the department have. Women students are also routinely asked to leave the class during certain discussions to make the male students feel “comfortable.” Rajveer uses the term “feudal patriarchal” to describe the environment in the department.

The threat of expulsion directed at Rajveer needs to be seen as the inevitable outcome of such shrinking of critical spaces within the universities and other crucial institutions of the nation. Rajveer’s story needs to be placed within the same continuum as the increasing repression of dissenting students at universities such as JNU and HCU, and within a larger context of increasing violence against women, dalits and minorities within the nation.

Rajveer notes that bSCEM has routinely spoken against such practices, and during such protests, the authorities — whether of the university or of the department — have given primacy to male voices. Rajveer tells us, “Unko lagta hai ki women ko koi na koi male hi guide karta hai, aur woh apne dimaag se faisle karne mein saksham nahi hain” (They think that women are always guided by some man or the other, and women can’t think or decide for themselves). Incidentally, Rajveer had continued with her political work even after the “warning” from the HoD. Representatives from bSCEM claim Rajveer was continuously harassed and verbally abused thereafter by Dr. Kaur, who found it difficult to come to terms with Rajveer’s political views and persona. According to Rajveer, “Jab koi woman student khadi ho kar unke saamne bolti hain to HoD ko sahan karna mushkil ho jata hai” (Whenever a woman student says anything, standing upright in front of her, it becomes difficult for the HoD to tolerate that).

According to bSCEM sources, when the results of the MPhil coursework were declared shortly afterwards, it was discovered that Rajveer had failed the exams. Two days after the results were declared, the HoD arbitrarily conducted a re-examination, without any formal consultation with the MPhil committee. bSCEM had formally written to the Dean of Examination, expressing an apprehension that the results would be biased against Rajveer. And they were.

Rajveer, along with her classmate Manpreet, who was also detained for similar reasons, began a hunger strike. They claimed there were irregularities in the MPhil exam results, and there was clearly a “bias” against Rajveer and other student activists. Consequently, they demanded that an independent committee should be formed to look into the matter. Along with these immediate demands, the hunger strike also included some long-term issues on which bSCEM had been mobilizing students within the department for some time. Such demands included the installation of drinking water facilities for the students within the department, better library facilities, and last but not the least, the demand that notices in the department should be written in Punjabi.

In fact, Rajveer points out, Hindi-English domination is a long-term issue within the department. The MA, MPhil or PhD syllabi are all written in English, while students who are writing their MPhil or PhD dissertations/thesis on Punjabi literature are required to turn in a translation of their work in Hindi or English, if it is written in Punjabi. Consequently, the question of linguistic hegemony within DU was an important issue within the movement. Rajveer told me, “Hamari to demand hai ki har department (history, economics, political science, environment, law etc.) ki kitaabe har language mein hona chahiye. Lekin DU mein to language departments mein bhi Hindi-English ki supremacy rehti hain. To yeh demand aur bhi door ki baat hain” (Our demand is to have every book in every other department, such as History, Economics, Political Science, Environment, Law, available in every language. But, in DU, where the Hindi-English supremacy operates even in language departments, this demand isn’t going to be met very soon).

“Hamari to demand hai ki har department ki kitaabe har language mein hona chahiye. Lekin DU mein to language departments mein bhi Hindi-English ki supremacy rehti hain. To yeh demand aur bhi door ki baat hain” – the question of linguistic hegemony within DU was an important issue within the movement.

On the first day of the hunger strike, the results of the re-examination were brought out. Manpreet had passed the exams, but it was found out that Rajveer has failed again. The students of bSCEM feel this was a planned move, undertaken by the authorities to “break the resolve” of the striking students. Meanwhile, the striking students weren’t allowed to bring bedsheets or blankets for staying on the university premises at night. It was cold outside, and it was only after the students raised slogans and made some militant speeches, did the security guards allow them to stay within the campus for the night. The hunger strike continued for the next three days – 26th to 29th November, 2018. But the university authorities did not send any representatives to open a conversation with the students. Neither was a doctor sent.

A doctor was sent on the night of day three, only after the student-activists had done another round of militant sloganeering in front of the Dean and Proctor’s offices. The doctor, bSCEM informs GX, opined that Rajveer needed to be hospitalized immediately. Otherwise, there is a high chance of kidney failure. Rajveer decided against going to the hospital, and decided to continue with the hunger-strike until all demands were met.

On the fourth day, as other student organizations and the general students on campus began to show their solidarity towards the striking-fasting students, the administration agreed to negotiate, and publicly accepted all the demands. Dr. Kaur, the HoD of the Punjabi department, agreed to form an independent MPhil committee that will look into the allegations of the irregularity in the exam results. bSCEM activists claim, Dr. Kaur made the agreement in front of a camera, and it is all recorded. Rajveer was asked to submit an application, based on which the MPhil committee will call a meeting. Rajveer duly submitted her application on the very next day. But even after five days, no meeting was called. Meanwhile, the strike had been called off.

According to the bSCEM activists, they kept up the conversation within the university, and while they were being asked to move from pillar to post – the Proctor, the Dean, the HoD – no one was ready to work according to the promises they had made in public. Rajveer observes that from 4th to 6th December, gheraos of different offices within the University were also organized. bSCEM activists feel strongly about the fact that the public assurance forwarded by the university authorities was a “tactic.”

“This administration believes,” the bSCEM representatives said, “it can break the spirit of unity of students through such under-handed tactics.” They also feel such tactics are completely congruent with the current political climate in the country, which thrives upon crushing any and all voices of dissent and thus destroying the “democratic spirit” of students. According to Rajveer herself, “Delhi University mein lagatar thodi bohut bachi hui space ko bhi khatam kiya ja raha hai. Humara Constitution citizen ko free speech ka right to deti hai, lekin humare educational institutions (jaise DU) mein is se opposite rules nikal kar aa rahe hain” (At Delhi University, there has been a consistent effort to destroy whatever little space that has been left. Our constitution does grant its citizens the right to free speech, but in our education institutions, like DU, it’s exactly the opposite kinds of rules that dominate).

In fact, Rajveer reminds us, the struggle at the Department of Punjabi need to be seen in the context of a larger structural nexus between the state and the university authorities. “Only a few days ago, there were notices sent by Delhi police. Anyone who would write on the campus wall or paste posters, will be fined and given a jail sentence for a year.” Earlier this year, the Delhi High Court had issued an order that every college within DU should put up two “Democracy Walls”, where the candidates and the organizations can put up their posters and slogans. Any organization or candidate found side-stepping this order, and pasting posters and slogans anywhere else on campus, would be disqualified. As if democracy can be bound by and to specific walls!

Delhi High Court had issued an order that every college within DU should put up two “Democracy Walls”, where the candidates and the organizations can put up their posters and slogans. Any organization or candidate found side-stepping this order, and pasting posters and slogans anywhere else on campus, would be disqualified. As if democracy can be bound by and to specific walls!

The fight, then, is ultimately about the question of access to and ownership of spaces. Who gets to decide how a given space is to be used. Who gets to decide when a given space is to be used. Who gets to decide who has the right to use a given space, and why. Who gets to decide on the penalization and punishments handed out to the transgressors. Rajveer was indeed a transgressor. A transgressor who had her own interpretation of what the university walls should be used for. And that is why, those who believe in the essential value of limiting slogans, propaganda, difficult and different opinions – the essential ingredients a democracy is constituted of – to specific walls, made every effort to spit her out of the spaces that compose the university system at large.

But the syllabus, too, is a kind of space. A literal space and a metaphorical space, at the same time. What or who is let into that space, has always been political. What is excluded from that space is also political. It might come as a surprise to the readers of this article that the poems of Pash are included in the MPhil syllabus in Punjabi at DU. Yes, Pash is a poet, whose work students pursuing an MPhil in Punjabi at DU read and analyse inside their classrooms. Yes, Pash is a poet on whom one can write an MPhil dissertation or PhD thesis. Yes, Pash is a poet about whom students write on their answer-scripts for the qualifying exams, and get their degrees. Rajveer asks, in the course of our conversation, “Aur Paash toh syllabus ka hissa hain. Us literature pe students jab discussion karne ki baat karte hain to woh khatarnaak kyon hota hai administration ke liye?” (And Paash is part of the syllabus. But why does it become so dangerous for the administration when students begin to discuss his work?)

Rajveer answers her own question: “Kyun ki agar syllabus ke baahar students Paash ki kavita ko padhenge to woh is structure pe sochenge aur sawaal uthana shuru kar denge” (Because if the students begin to read and discuss Paash outside of the syllabus, they will begin to think about this structure and will begin to raise questions). In other words, Paash locked into the syllabus is safe. Paash let loose on handwritten wall-magazines by students is dangerous, and Paash written on the walls of the university campus in forms of fragmented quotes– even more so.

“Aur Paash toh syllabus ka hissa hain. Us literature pe students jab discussion karne ki baat karte hain to woh khatarnaak kyon hota hai administration ke liye?” Rajveer answers her own question: “Kyun ki agar syllabus ke baahar students Paash ki kavita ko padhenge to woh is structure pe sochenge aur sawaal uthana shuru kar denge”

I asked Rajveer, why wall-magazines. What relevance can wall-magazines and posters possess in the age of social media? Rajveer responds by drawing a half-sarcastic analogy. “Yeh sawaal bhi ho sakta hai ki regular classes ki kya zaroorat hai! Ghar baithe online classes bhi ho sakta hai” (This question too can then be raised that there is no need for regular classes. One can sit at home and take online classes). Then, she provides a fuller explanation. “Wall magazines aur posters se ek toh universities mein different thoughts ke upar discussion ki spaces reclaim karna sambhav hota hai. Aur jab fascist forces ka bachi-kuchi democratic spaces pe bhi hamlaa teji se badh raha hai, tab universities mein ek resistance ka culture establish karne ki zaroorat hai” (Through wall magazines or posters, on the one hand, it is possible to reclaim spaces within universities within which discussions on different thoughts can be held. And when the attack of the fascist forces on whatever little democratic spaces we are left with is rising, it is essential to establish a culture of resistance). Rajveer and her comrades believe wall-magazines can establish such cultures of resistance.

They do not reject the use of social media. In fact, like most student organizers and organizations of our times, they make creative uses of social media. But, for them, these virtual spaces do not replace physical spaces or the struggles over them. In fact, the two complement each other, as Rajveer points out.

As we rounded up the conversation, I could not help comparing Rajveer with another young woman whose name features in our recent memories in complicated ways. For the intellectuals of the liberal mainstream, like Shiv Viswanathan, she is the reminder of the “chilly justice of the Gulag.” For journalists like Bhanuj Kappal, she is an anti-caste pioneer, who “broke” “savarna feminist” “rules.” Yes, I am talking about Raya Sarkar, whose LoSHA (List of Sexual Harassers in Academia) made her visible in social media, gaining interviews from feminist and non-feminist online sources alike.

In contrast, Rajveer’s story has received almost no media attention. Raya Sarkar claimed her Singaporean citizenship and physical location in the USA – away from India — would insulate her from the backlash. Rajveer has no such privileges. Rajveer fought, and continues to fight within the spaces where she belongs. Additionally, unlike many women who anonymously sent the names of their professors to Sarkar’s list, for the fear of having their careers “destroyed,” Rajveer’s risked her career.. Raya, said, in an interview with NewStatesmanAmerica, “They did not approach any committee in place because it is exhausting. They are scrutinised and singled out in their institutions.”

Yes, it is exhausting to register a complaint against a harasser in liberal institutions – sexual or otherwise. Yes, anyone who does so is scrutinized and singled out. There is no reason to deny the sheer realism of Raya’s pronouncements. And, no, I am not trivializing the fear that follows many women students who are harassed by the male faculty within their respective university or college campuses. Nor am I in favour of an uncritical advocacy of “due process.” And, needless to say, there is absolutely no question of trivializing sexual harassment. My observation is of a slightly different order. There is a curious demand in Raya’s commentary. It is the demand that things need to change for better, but without any personal cost. Activism, in Raya’s version, is bereft of labour. Activism, in Raya’s version, is a non-acknowledgment of how that labor changes an individual. And, often, at a great personal cost. Activism, then, in Raya’s narrative, becomes too easy. Like going out to shop. Like consumption.

What I am pointing out is that today’s India is seeing the emergence of two kinds of feminism. If the first one is represented by Raya Sarkar, which by and large thrives on constructing a figure of a victimized young woman, whose only agency lies in narrating – and often anonymously – the story of her sexual violation, the other, represented by Kanupriya of Punjab University, Pinjra Tod and Rajveer, believe in looking power straight in the eye. The latter, as multiple examples from the recent past will show, believes in constructing figures of feminine resistance, believes in moving past the figure of the victimized woman, on whom powerful men only act upon. And, most often, this effort to create a culture of feminine resistance takes – has to – the form of militant everyday organizing. The latter’s work, thus, is exhausting. Yes, many of them are often scrutinised within their respective institutions. Yes, many of them are singled out, as Rajveer was. But that is what activism is about. Nothing in this world changes for the better without considerable personal costs in some form or the other.

What should be noted here is a seemingly simple fact. Rajveer has been singled out for her political opinions, for her activism, and more specifically, for being a woman-student who dares to speak back to power. Yet, Rajveer’s experience of being singled out did not lead her to flee the complicated spaces of mass mobilizations and collective struggles. Instead, the very issue of Rajveer’s being singled out became the cause for further mobilizations for her friends, comrades, organization, and obviously, her own self.

And, there are partial victories. At the time of uploading this article, the department has reached a settlement. Rajveer’s exam had been re-conducted. But, the other demands – those demanding structural changes – remain unattended. There have been oral assurances, but no concrete steps so far. A representative from bSCEM told me, “Rajveer had shown a great resistive strength. She was never ready to give up on the hunger strike. Seeing her deteriorating health, we asked her to call it off. But, she never moved away. She always connected this struggle with the democratic struggle of women against the feudal patriarch, social and state institutions.

It is perhaps premature to say these two forms of gender mobilizations – one represented by the likes of Raya Sarkar, and one represented by the likes of Rajveer — are at radical odds with each other. But it is perhaps not too difficult to see that they differ in their approaches to power, patriarchy and resistance. And, for now, that difference itself needs to be noted.

Rajveer tells me, “Mujhe is system pe gussa aata hai. Or ye gussa har ek woman student ko hona chahiye” (I am angry at this system. And this anger should be felt by every woman student). For her, the future is clear. “Baaki puri Delhi University mein democratic space ke liye ladaai jaari rahegi. Punjabi department mein is movement ne bohot positive asar paida kiya hai. Kyuki students mein anti-women practice ke khilaaf bolne ka honsla aaya hai. Hamari ladaai yahaan pe khatam nahi hogi” (The struggle to claim democratic spaces throughout the rest of Delhi University will continue. Within the Punjabi department, this struggle has yielded lots of positive results. Because, the students now feel empowered to speak openly against the anti-women practices. Our fight hasn’t ended).

No, Rajveer and her comrades do not believe in “whisper campaigns”, even though they might use it as one of their many tools. They believe in shouting slogans, making speeches, rallies, gheraos and hunger strikes. And, yes, these things are exhausting and do not provide the protection of anonymity and distance that digital activism often accords. But that is what being an activist within a community means. That is what being an activist within a specific institution means.

It is perhaps premature to say these two forms of gender mobilizations – one represented by the likes of Raya Sarkar, and one represented by the likes of Rajveer — are at radical odds with each other. But it is perhaps not too difficult to see that they differ in their approaches to power, patriarchy and resistance. And, for now, that difference itself needs to be noted.

The author is a writer and an independent media activist. All photos are courtesy Bhagat Singh Chhatra Ekta Manch.