On the day when millions of workers across the country struck for Minimum Wage, the Parliament almost unanimously passed the 124th Constitution Amendment Bill, introducing reservation for the socially and educationally forward classes. Coming to be called the ‘Upper Caste Quota Bill’ in common parlance, this Bill is being seen as Modi Government’s last minute desperate attempt at winning back upper caste votes for the 2019 General Elections. Almost every other electoral party, from CPI(M), Congress to the BSP, supported the move. Here we look at what’s new and what’s not about the Government’s move to introduce ‘Upper Caste Quotas’. In an upcoming article, we will discuss the larger Constitutional crisis at hand, and look into the history of legislative battles around the idea of ‘backwardness’, reservations and ‘equal opportunities’. Siddhartha Dasgupta writes.

Constitution (124th Amendment) Bill, 2019

The Parliament on Wednesday passed what is being popularly called the ‘Economic Reservation for Upper Castes’ Bill. At the outset it must be mentioned that the actual Bill that was tabled is a Constitution amendment bill – a legally necessary precondition for the Government’s announced policy of reserving 10% of public jobs, and public and private education seats (both State aided and unaided) for ‘economically backward’ sections not covered under social reservations. The Government still has to introduce the required Memorandum for the actual reservation framework.

The Constitution (124th Amendment) Bill, 2019 came on the very same day when millions of workers across the country went on a nation-wide strike demanding a guaranteed minimum wage of at least Rs 18000, and other demands including creation of jobs, right to form Unions, etc. The same Government that is denying this minimum wage that would amount to an income of Rs 2.16 lakh per annum for a typical working class family, has announced reservations for ‘forward class’ families with incomes up to Rs 8 lakh per annum. The only necessary criteria: they can’t belong to either the so-called socially and educationally backward classes or the Scheduled Castes and the Scheduled Tribes – “classes mentioned in clauses (4) and (5) of Article 15”, as the legal lingo goes.

[metaslider id=”6295″]

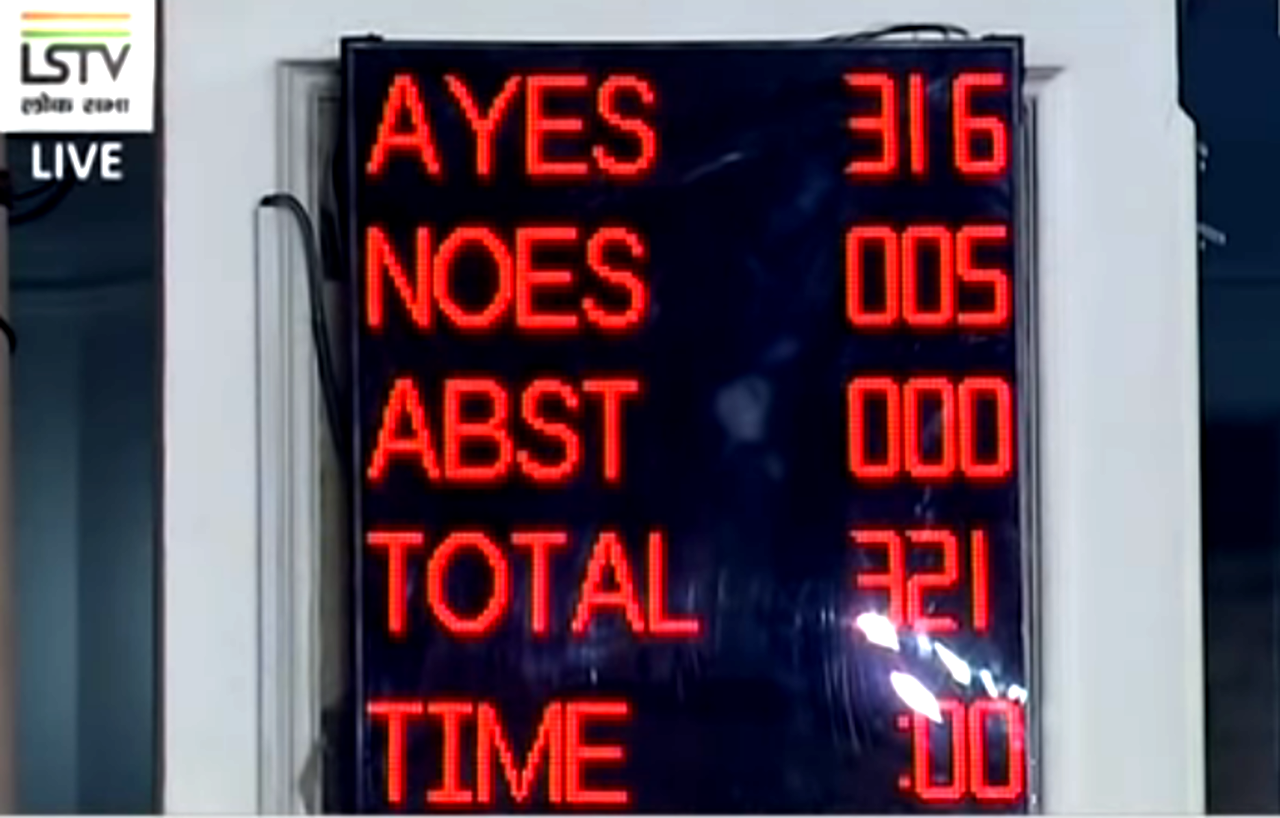

The Bill proposes amendments to Articles 15 and 16 of the Constitution, in order to pave legal way for the so-called ‘Economic Reservations’. It is alleged to have been drafted over 3 days, under topmost secrecy, at the residence of Narendra Modi, approved by the Cabinet on Monday, tabled and passed almost unanimously in the Lok Sabha on Tuesday [there were only 5 votes against], and passed in the Rajya Sabha on Wednesday. The business of the Rajya Sabha was extended by a day (till Wednesday) in order to pass the bill.

The same Government that is denying this minimum wage that would amount to an income of Rs 2.16 lakh per annum for a typical working class family, has announced reservations for ‘forward class’ families with incomes up to Rs 8 lakh per annum.

Social Justice Minister Thawarchand Gehlot described this as a “happy moment for all the sections, including Brahmin, Thakur, Patel, Baniya”, while placing the Bill before the Lower House. Gehlot claimed the issue has been debated for long in public and the government has consulted the common people and experts and their opinions have been taken. He rejected the opposition’s demand for referring the bill to a Joint Select Committee for detailed consideration, saying it has already got delayed enough. “This bill ensures ‘sabka saath, sabka vikas’,” said Finance Minister Arun Jaitley, making this the first time the Government has come clean on what Narendra Modi’s election chant really meant.

Opposition caught off-guard

Reservations for the economically weaker sections of all communities ‘without disturbing the existing reservation for under-privileged communities’ has been a promise of every political party in the country for long now. This, together with the secrecy in which the Government moved on this matter, meant that almost all of them were caught off-guard – not being able to back out on something that has been their own promise as well, not being able to take the credit for such a move, and having to support the Government on the issue.

“It would have been better had the government taken the decision not right before its tenure ends, but much earlier. So that this new reservation policy could be implemented in a proper way or provide true benefits to the poor Savarnas”: Mayawati

Their embarrassment and awkwardness was clear from the array of reactions. “We are not against it (the bill). We support the concept. But the way you are doing it, (your) sincerity (is) questioned. Send it to JPC, why are you in hurry?,” said KV Thomas of Congress. BSP Chief Mayawati said reservation for “poor Savarnas” (poor upper castes) had in fact been a long-standing demand of the BSP, adding that the Government should have actually done this earlier. “It would have been better had the government taken the decision not right before its tenure ends, but much earlier. So that this new reservation policy could be implemented in a proper way or provide true benefits to the poor Savarnas,” she said.

The ‘criticisms’ from the spectrum of opposition parties were few, and almost sounded like a lovers’ quarrel. Here is an essential sum-up: “Election stunt” (Every Opposition party); “Too late, should have been done earlier and properly implemented by now” (BSP); “What does reservation mean since there are no jobs anyway” (LJP); “Too hasty, send it to a Joint Parliamentary Committee to do it in a more sincere fashion” (Congress); “Won’t hold up in the Supreme Court” (TMC); “The cutoff of 8 lakhs per annum is too high and the true beneficiaries won’t be the real poor upper castes” (CPI(M)).

AIMIM chief Asaduddin Owaisi was one of the 5 LS members who opposed the Bill, saying, “This is a fraud on Constitution and insult on Babasaheb Ambedkar. Our Constitution doesn’t recognise economically-backward. Have the Savarnas ever faced untouchability? There is no empirical data to show the Savarna people are backward.” Deputy Speaker M. Thambidurai of the AIADMK, walked out saying that reservations for economically weaker sections cannot ensure social justice.

“This is a fraud on Constitution and insult on Babasaheb Ambedkar. Our Constitution doesn’t recognise economically-backward. Have the Savarnas ever faced untouchability?”: Asaduddin Owaisi

What in this is not ‘new’

This is not the first time that a Government of this country or its states has tried implementing economic reservations. In 1991, PV Narsimha Rao had issued an Office Memorandum reserving 10% of Government jobs for economically backward sections of people “who are not covered by any existing schemes of reservation”, in order to quell the post-Mandal Commission upper caste rage across the country. But the following year, a 9-judge SC bench struck it down (the Indra Sawhney case).

In 2008, the CPI(M) Government of Kerala, under Chief Minister VS Achuthanandan, decided to reserve 10% seats in all graduation and post-graduation courses in government colleges and 7.5% seats in universities for students belonging to economically backward among ‘forward’ communities. Kerala Muslim Jamaat Council challenged this in High Court, and then the Supreme Court. The case is still pending.

In 2008, the CPI(M) Government of Kerala, under Chief Minister VS Achuthanandan, decided to reserve 10% seats in all graduation and post-graduation courses in government colleges and 7.5% seats in universities for students belonging to economically backward among ‘forward’ communities.

Various Governments and political parties in the history of this country have used the carrots of ‘pro-people’ economic reservation policies, specifically when crucial elections have knocked at the gates. None of these attempts have however stood up the scrutiny of the Courts, which has led many to claim that Modi’s move also is fated to die its natural death in the Supreme Court. Though by the time that happens if at all, the ’19 Elections would have happened, and political benefits if any, would have been reaped.

In fact the State is mandated to decide “backwardness”

Article 16(4) of the Indian Constitution entrusts the State with making provisions for the reservation of appointments or posts in favor of any backward class of citizens which, “in the opinion of the State,” is not adequately represented. Accordingly, the Union Government has set up multiple Commissions to decide upon what is a “backward class”, and what should be the criteria for deciding “backwardness”.

Kaka Kalelkar Commission, the first such Backward Class commission set up in January 1953, listed out 2,399 castes as ‘socially and educationally backward’ (for short ‘SEBCs’) on the basis of an 11-point Social, Educational and Economic criteria. The Nehru government, not satisfied with the commission’s proposed criteria for identifying ‘backward classes’ under Article 15(4), ignored the report.

The Second Backward Classes Commission (popularly known as Mandal Commission) was set up about twenty-four years after the First Commission submitted its Report, on 1st January 1979 under the Chairmanship of Shri B.P. Mandal. One of the terms of reference of the Commission was to determine the criteria for defining the SEBCs.

Based on the recommendations of the Mandal Commission, the VP Singh Government issued a memorandum in 1990, reserving 27% of Government of India jobs, to be extended to public sector undertakings and financial institutions including public sector banks, for the SEBCs.

One year later, after the change of the Government at the Center, PV Narasimha Rao amended the VP Singh Office Memorandum (OM), issuing a fresh OM that said [relevant parts]:

(i) Within the 27% of the vacancies in civil posts and services under the Government of India reserved for SEBCs, preference shall be given to candidates belonging to the poorer sections of the SEBCs…

(ii) 10% of the vacancies in civil posts and services under the Government of India shall be reserved for other economically backward sections of the people who are not covered by any of the existing schemes of reservation.

“Till now, the Central Government has not evolved the economic criteria as contemplated by the later Memorandum,” noted the Supreme Court in its order in the Indra Sawhney case in 1992, striking down the Narasimha Rao OM. It is important to note that the main point of the 9-bench judgment was not that ‘economic backwardness’ is irrelevant for the question of reservation, but that there must be proper criteria and procedure to judge such backwardness.

Not unlike the Narasimha Rao Government, the Modi Government made no attempts in evolving any kind of objective criteria for deciding who is ‘economically backward’. Quite to the contrary, the present Government has constantly fiddled with data regarding economic condition of people, joblessness, etc., fudged with the very mechanisms to measure and analyse such data, and made it extremely difficult to get access to the existing data.

Not unlike the Narasimha Rao Government, the Modi Government made no attempts in evolving any kind of objective criteria for deciding who is ‘economically backward’. It did not set up any Commission to take up a comprehensive study to decide what it means by ‘economically backward’ among the upper castes. Any such Commission surely would have told the Government in the least that it does not make logical sense to tax those with more than 2.5 lakh annual income while also declaring anyone with less than 8 lakh annual income as ‘Economically Backward’. A ‘pro-poor’ Government should not be, even on paper, taxing its ‘economically backward’ people. Quite to the contrary, the present Government has constantly fiddled with data regarding economic condition of people, joblessness, etc., fudged with the very mechanisms to measure and analyse such data, and made it extremely difficult to get access to the already existing data. This (and the previous) Government did not even release the full data from the Socio-Economic Caste Census conducted in 2011. Surely that data would have enriched the ‘public consultation’ and ‘expert opinions’ that Mr. Gehlot suggests were conducted by the present Government.

What is new this time

What is structurally new with this latest attempt at introducing economic reservations, is the complete side-stepping of any of the usual processes for arriving at an objective, meaningful definition of economic ‘backwardness’. The Modi Government has learnt from the mistakes of its predecessors, like Narasimha Rao who relied on Office Memoranda, etc. that were struck down by the Court, and realised it is impossible to introduce ‘Upper Caste Quota’ without an amendment of the Constitution. This is of course in line with the RSS’s declared hatred for the Indian Constitution.

The road to the current Amendment of the main legal text of the land was however not laid by the RSS, but by the Supreme Court itself, last September.

This was to be expected…

On September 26th 2018, in a historic judgment, a 5-judge SC bench under then Chief Justice Deepak Mishra upheld the ‘creamy layer’ argument in the context of reservation for Dalits and Adivasis. “We reiterate that the ceiling limit of 50%, the concept of creamy layer and the compelling reasons, namely, backwardness, inadequacy of representation and overall administrative efficiency are all constitutional requirements without which the structure of equality of opportunity in Article 16 would collapse,” the Court said.

The road to the current Amendment of the main legal text of the land was however not laid by the RSS, but by the Supreme Court itself, last September.

There have been several landmark judgments by the apex court where it refused to apply the ‘creamy layer’ argument to SCs and STs, even as they did not necessarily reject the idea of reservations based on ‘economic backwardness’. In the 1992 Indra Sawhney case, the 9-judge bench, while noting that “exclusion of such socially advanced members will make the ‘class’ a truly backward class and would more appropriately serve the purpose and object of Clause (4),” added immediately that “this discussion is confined to Other Backward Classes only and has no relevance in the case of Scheduled Tribes and Scheduled Castes.” Earlier in 1985, in the 5-judge bench Vasant Kumar case, Justice Chinnappa Reddy had demolished the idea of a ‘creamy layer’ for backward classes: “How can it be bad if reserved seats and posts are snatched away by the creamy layer of backward classes, if such snatching away of unreserved posts by the top creamy layer of society itself is not bad?” he wrote. In the 2008 Ashok Kumar Thakur judgment, the 5-judge bench order stated, “‘Creamy layer’ principle is one of the parameters to identify backward classes. Therefore, principally, the ‘creamy layer’ principle cannot be applied to STs and SCs, as SCs and STs are separate classes by themselves.”

“It is only those persons within that group or sub-group, who have come out of untouchability or backwardness by virtue of belonging to the creamy layer, who are excluded from the benefit of reservation”: SC judgment, 26th September 2018

Overturning all of these judgments, and in a way many senior lawyers claimed was unConstitutional, the 2018 Deepak Mishra judgment fundamentally revamped the way social and economic backwardness, and the conflict between the two, will be seen now on in this country. “The caste or group or subgroup named in the said List continues exactly as before. It is only those persons within that group or sub-group, who have come out of untouchability or backwardness by virtue of belonging to the creamy layer, who are excluded from the benefit of reservation,” the court order said.

Indira Jaisingh, a petitioner in the 2018 case had argued that the five-judge Ashok Thakur judgment could not be overruled by another five-judge bench. “In my opinion a constitutional amendment is on the cards soon,” said Jaisingh. This judgment now is what Narendra Modi hopes will uphold the validity of his amendment.

[In an upcoming piece, we discuss the Constitutional crisis between ‘Equality for All’ and ‘Protection for Some’ and trace the history of this conflict, in an attempt to investigate how the Modi Government bypassed, and tried to erase, an entire history of serious legislative debates, in its path to possibly the last ‘jumla’ of this regime. Stay tuned.]

The author is a political worker and a freelance journalist. [All emphasis used in the article are by the author.]