Few days back, Kolkata Uber and Ola drivers and operators withdrew their vehicles in the middle of the peak holiday season, protesting against severe financial crisis caused due to the predatory business policies of these companies. Many cab drivers burst into spontaneous militant protests across various parts of the city, preventing other cabs from operating. There were also reports of some vehicles being damaged, and passengers being asked to get off. Mainstream media immediately demonized the protests citing “inconvenience faced by the passengers”, and the TMC-led Online Cab Operators’ Guild – biggest organisation of online cab operators in the city – distanced itself from the protests after having themselves called for a strike. The crisis of the cab drivers persists however, and the rage continues to simmer. This is Part One of a GroundXero coverage, where we discuss the economic crisis faced by the tens of thousands of online cab operators in the city.

“The Dream has failed”

Around 4 years back, when they first launched their business in India, including in the city of Kolkata, online cab service providers had promised people earnings of more than one lakh rupees a month. But today, many vehicle owners are not even in a position to pay their EMIs to the banks. The average rate of revenue for these cab operators has slumped down to ₹10-11 per km, while the rates for normal AC taxis in the city are more than ₹18/km. “We have been demanding an increase in the rates for a long time now, but the companies are not responding. Our dreams have failed,” lamented one of the vehicle owners who is also a working committee member of the West Bengal Online Cab Operators’ Guild. Last Monday when a group of vehicle owners and drivers went to the Salt Lake office of one of the online cab companies to get their IDs unblocked, the company called the police, and the drivers were lathi charged, allegedly injuring 3 to 4 of them. Incidentally, this slump in the rate comes at the same time when the cab fares for customers have risen steadily.

Initially when the number of online cabs were still low and the rates high, a vehicle owner would typically earn around ₹40k per month, after paying the driver and taking care of other costs. “Now I earn only ₹12k to 13k per week from the trips, from which I have to take care of the daily costs. For 15 trips in a day, I have to pay the driver ₹ 900, the fuel cost comes up to around ₹800. And then you have daily maintenance costs associated with running a commercial vehicle, amounting up to more than ₹300. This means an expense of more than ₹2000 per day. You do the math now,” explained one vehicle owner who is incurring a net loss on a regular basis. The rate of ₹60 per trip for the driver is a market rate the cab owners have fixed. Uber or Ola does not take any responsibility in fair wages being paid to the driver.

Anti-Uber protests have been going on for years now in the US, amidst growing financial crisis and regular suicides among the drivers and operators. Uber faces multiple big lawsuits in its home country for labour law violations and other offenses. Photo: Eric Pendzich/REX Shutterstock

Our interviews revealed, many people have bought vehicles using loans obtained from mortgaging gold or land deeds. Many have taken loans from informal sources, at high interest rates of 10 to 15 percent per month. Many of them are still paying their EMI’s. “We are stuck. The drivers are also now used to working at ₹900 per day. They can’t cut down on their family expenses, so they won’t work for any less. We have to also pay the police extortion money regularly,” he added.

“I used to earn ₹10,500 per month from driving a private vehicle. After a while the wage got stagnated, and I decided to drive my own vehicle, and earn as much as I could. Last August I took a loan, bought a vehicle and registered with Ola. I have to pay an EMI of ₹14900, which is much more than what I should be paying. But I still agreed since I had no other choice,” said Jhontu Mondal, an Ola cab driver. Meanwhile Mondal’s car had started giving trouble and he found out he had been duped with an “accident car”. “I asked the bank to take the car back, but they said I’d have to forgo ₹60k, and I’d still have to pay the interest. So I had to keep the vehicle, there was really no option,” he went on. The ₹10 to ₹11 per km that he earns now is hardly enough to maintain his family, which now primarily depends on his wife’s sewing work for sustenance. “I tried talking to the company people, but they are not interested in talking to us. After trying various things, today I have come to this Union office to enlist my name. Let’s see what happens. I am hoping dada (TMC leader Madan Mitra, President of the West Bengal Online Cab Operators’ Guild) will be able to do something. Phense gechhi didi [I am stuck now sister],” Mondal said. Over and above, Jhontu Mondal recently discovered that his vehicle has pending old traffic violation cases, to the tune of ₹35k. A huge number of cab drivers in the city, including the yellow taxis and not just the Ola or Uber cabs, have been served with arbitrary cases recently for petty traffic violations or sometimes even for non-violations, and are being hounded by the police to pay up. The police administration has in fact announced a 60 percent discount, for those who settle pending cases by Jan 14th, to incentivize the payments. “I can’t even sit with a begging bowl on the street because I don’t even look like a real beggar. Ei cheharay ke bhikkhe debe?! I go out for work early in the morning, and drive till 2 in the night. I am losing my breath, and my health. I am now thinking of taking shelter in some ashram, I don’t see any other option,” Mondal added.

I should have rather bought 10 rickshaws instead, it would have been much better. At least I would be independent, I would be working within a fixed area. Here I have no control on where I would be asked to go!

The exploitative economic model of Ola and Uber runs much deeper than just low rates for drivers. Many drivers alleged that the special offers of “10 percent, 20 percent less” on the Uber or Ola services in fact come at the cost of the vehicle owners. “The company takes that money from us. They don’t bear the cost, we earn 10% less, 20% less on such trips,” one of them alleged. When the payment is made through Paytm, the cut from the drivers is 30 percent instead of the usual 26 percent [for Uber]. “Recently I had a booking from the Airport to Behala. The customer paid using Paytm. The App on his phone showed ₹780. But when I dropped him, I got only ₹330. So basically Paytm gets its cut, but that cut is not taken from Uber or Ola, it is taken from me! If it was paid directly without Paytm, I would have to pay ₹100 for the Airport charges and 26% to Uber. I would have got around ₹480. But there is nothing I can do about this, I have to agree to be paid through Paytm because the customer wants to pay using Paytm! I drove for 29 km to earn only ₹330,” said Asok Banerjee, a vehicle owner with Uber who drives his own vehicle. “I should have rather bought 10 rickshaws instead, it would have been much better. At least I would be independent, I would be working within a fixed area. Here I have no control on where I would be asked to go!”, he added. “One day I was completing a trip at Nagerbazar, and they gave me a booking at Ruby hospital [more than 15km away]! Once they blocked my ID while I was at the Airport, and I had to drive back the empty vehicle home all the way to Alipur, 28 kms away!” told another driver.

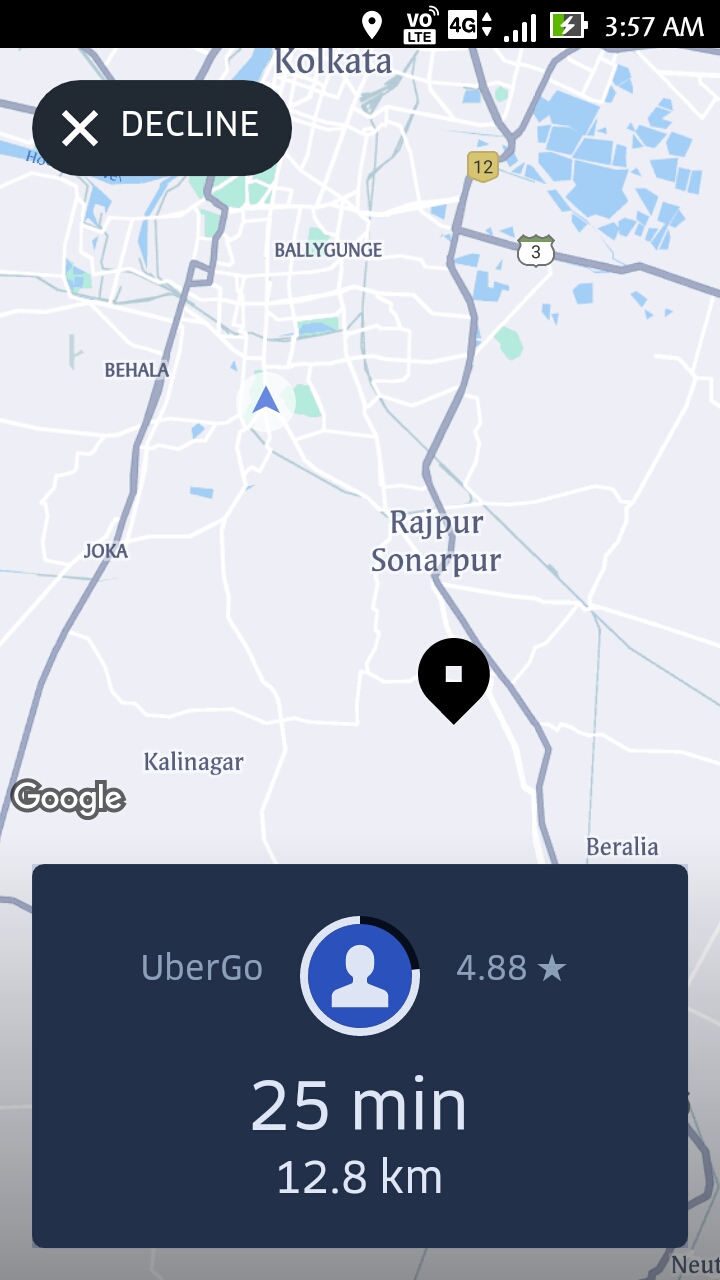

Its usual practice for these companies to assign bookings at far off locations, at times even 13km away

“Many times I travel 10 km for a pickup, and the trip is only for 2km. How is this sustainable for me? Often the customer cancels just as I am reaching to pick up. Which means I had to drive up the empty car all the way, for nothing,” alleged one of the drivers. “Every now and then they are taking cuts from the payments in the name of ever new surcharge, etc. Initially, both the driver and the owner would get a message about the billing amount. But now over the years as a large number of vehicles have signed up with these companies, they are showing their true colours, because there are excess vehicles now,” alleged another Ola driver. “These companies are nothing more than a bunch of middlemen, and they are cutting one-fifth from what actually should have been our own earnings,” said Mr. Banerjee.

The online cab companies maintain that they are only a “service providing platform” and not a transportation company, and that the drivers and operators are not their employees, but business partners. This implies that the companies hold no responsibility in accordance with the labour laws.

The Revenue Model

GX spoke with one of the Ola vehicle owners, who on conditions of anonymity gave the details of his own finances. This may only be representative of a particular case, but still gives some idea about the rough picture. He had made a one-time down payment of ₹2.3 lakh for buying the vehicle. Below is a breakup of his yearly expenditures:

Taxes – ₹16.5k

Insurance – ₹23.5k

Road permit (to be paid annually, except for first two years) – ₹10k

Certificate of Fitness – ₹8k

Mandatory Repairs for Certificate of Fitness (for new car) – ₹8k

Compulsory Servicing (every 2 months, costing ₹10k each time) – ₹60k

EMI (₹500 per day for a loan of ₹5.3 lakh) – ₹1.83 lakh

The daily maintenance cost comes to around ₹850 per day. This excludes daily washing, small repairs, traffic police extortion, bribes for receiving certificates, and other such costs.

Here is an example of typical “Incentives” from Uber:

60 trips in 4 days – ₹1800

45 trips in 3 days – ₹1350

100 trips in 1week – ₹6000

Ola also has similar offers and incentives, though they keep changing from time to time, and driver to driver. While Ola deducts 20 percent from the fares, Uber deducts 26 percent because of GST. The person speaking to us, said that he typically completes 22 trips daily on average on his Ola vehicle, earning ₹4400 (including the incentive). After the company’s 20 percent deductions, he gets ₹3520. 1 percent of this amount is actually deducted for TDS that he is supposed to get later after he pays some additional fees, but we leave it for the purpose of this calculation. The diesel cost for 22 trips (around 300km) is ₹1200. He pays the driver ₹60 per trip, amounting to ₹1320. Thus, at the end of every day, he is left with around ₹1000. If we deduct the daily maintenance costs (calculated earlier) of ₹850 from this, we are left with a daily earning of around ₹150. It is to be noted that completing 22 trips a day requires around 16 hours of driving. And these rates fluctuate a lot. There have been days when in order to reach ₹4400 on the bill, the driver has to complete as many as 28 trips.

These companies are nothing more than a bunch of middlemen, and they are cutting one-fifth from what actually should have been our own earnings

Such meager end amounts like ₹150, match with the accounts of many other drivers who said, “We consider it a good day if we come back home with ₹500 at the end of the day.” The monthly earning @₹150/day comes up to ₹4500 – not only far less than the initial promise of “more than rupees one lakh of earnings per month”, but also much less than what the traditional neighborhood car rental agency used to earn. Many of these agencies have been slowly wiped out from the city, others have had to switch their business models, due to the ever growing duopoly of Uber and Ola. It’s worth pointing out that the above calculation does not even include the initial down payment amount required to buy the vehicle.

Dara Khosrowshahi (CEO of Uber) and Bhavish Aggarwal (Co-Founder and CEO of Ola Cabs). Source: EDTimes

Ola operates across 169 cities in India, Australia and UK, while Uber has spread its business to 785 cities across the world. According to some reports, Bhavish Agarwal owned Ola Cabs’ revenue reached ₹1286 crore in the last financial year, and that of the American company Uber has reached ₹2.5 lakh crores. Just over this past one year, their revenues in India grew by 70% and 85% respectively. Incidentally, Uber has faced multiple big lawsuits in the US for labour law violations and fraud, after which its American business took a hit. This was when they spread to other third world countries that included India. Over the past couple of years there had been regular news of Uber and Lyft (another online cab company) drivers committing suicides in the US because of financial desperation.

This was a brief account of the financial crisis that the online cab operators are dealing with. In Part 2, we report on the other aspects of the crisis – punishments and trickeries from behind the smokescreen of an “App” and harassment from customers high on their entitlement to convenience. We also discuss the role of the Government and the online cab operators organisations in negotiating with this crisis.

Photos are from the Internet.

Too good a report to understand actually what is going on… beside of

that it is a warning to the ones who wants to become the Ola/Uber partner