Nandini Dhar writes: “This essay, at the end of the day, is a book review. It is a review of a children’s book called I Will Save My Land, written by Rinchin, the writer and activist based in Chattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh. Yet, before I go into the book review “proper,” I will talk about many other things, not the least of which would be a brief discussion on the politics of children’s literature. Which will, invariably, bring onto the discussion, the politics of childhood, because, in India, right now, childhood is a deeply political category.”

Kailash Satyarthi, India’s 2014 Nobel Laureate, attended this year’s RSS’s annual Vijaya Dashami celebrations at Nagpur, and amidst receiving the salute the RSS way, claimed, “In doing this and achieving the goal of building a great and child friendly nation the participation and leadership of conscientious youth is absolutely essential. I request the youth from Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh to take a lead on this path for saving the present and future of our motherland. If the branches (shakhas) of the Sangh situated in almost all villages across the length and breadth of our country serve as a firewall to protect this generation of children, then all the generations to come will become self-sufficient in protecting themselves.” What Satyarthi meant by “this”, was a celebration of Ramleela in his ashram for children, where the mythical rakshasha, Ravana, was symbolically killed and destroyed, thus creating a moment of informal, mythological education for the children. Replete with imageries of Ravana as evil, and Rama as good, both Satyarthi’s speech and his recounting of the informal moments of pedagogy within the institutions he has created, touted the official RSS cultural-political line that does not leave any room for any kind of critical distance. Furthermore, in thrusting upon RSS the responsibility to “protect” the children of the nation, Satyarthi’s speech provides further legitimacy to the Hindu religious right’s project of colonizing the nation’s childhood through systematically undertaken cultural and educational projects.

Satyarthi’s speech also actively constructs an image of a child. That image centers on the figure of a hapless child, a blank slate on whom the adults can write their own political agenda according to their will. Because a hapless child is also without any agency whatsoever, that child has to be “protected” by RSS youth. Of course, this culture of creation of the figures of victimized children and women is nothing new in the nation’s Hindu rightwing politics. Interestingly – as was obvious in Hadiya’s case – in contemporary India, it is precisely a language of infantilization of adult women that often dominates the state’s rhetoric when it comes to one of its core projects – controlling women’s bodies and lives . In other words, metaphors of childhood and children are deeply intertwined with the Hindu right wing’s overarching politics, which includes, but is not limited to its gender and sexual politics. While such an issue demands discussions on its own right, this essay is not necessarily about the Hindutva strategy of infantilizing women. Instead, it throws light on childhood itself. The “real”, material childhood, so to say. Childhood, in this essay, is not a metaphor per se, to talk about oppressed adulthood. In other words, this essay begins from a very simple political premise. It begins from the premise that we must ask ourselves, what kinds of images and stories of childhood can we come up with that do not recreate and reinforce the very philosophy and politics of childhood that RSS is attempting to institutionalize.

To begin with, childhood has always been a deeply political category in the history of capitalist modernities. In fact, there has never been a time in the history of modernity in India that childhood has not been politicized. Barely a little more than one fifty years ago – in 1835 — wasn’t Thomas Babington Macaulay proclaiming the need for an education system that would “form a class who may be interpreters between us and the millions whom we govern, –a class of persons Indian in blood and colour, but English in tastes, in opinions, in morals and in intellect”? Can we actually think of connections between what was then the Macaulayization of education, and what we now term as ?

A proclamation that still possesses the power to startle us with its sheer directness, Macaulay’s Minutes nevertheless establishes the fact that education has always been a political project, and always will be. And, if education is a political project, then those who are to be educated – the children and the youth – are indeed to be treated as political beings.

Consequently, even a quick cursory look through the archives of the children’s literatures in most countries would reveal a directness of political rhetoric which, when, thought through, befuddles the adult mind. Because, inherent within our very understanding of children’s political selfhood, is a double bind. As adults, we tend to think, children can be politically inculcated. Yet, we also think, children are not political subjects to begin with. Children, after all, don’t vote. And, because they don’t vote, children irrespective of class, caste, race, religion or gender, cannot, in the perceptions of the very foundational politics of representative democracies, be political subjects.

In our adult perceptions, children are often described as “innocent.” Needless to say, the very word “innocence,” when used to refer to children, comes to signify a lack of subjectivity of any kind. And, this is often times also the dominant perception that we — the adults — bring onto the discussions of children’s literature too.

Children’s literatures, according to the default adult perception, are “simple” texts. These are texts which must also reproduce the cuteness and sweetness we associate with children and childhood. As a result, our discussions of children’s literature very quickly assumes a moralistic tone. We ask each other, should children be exposed to violence within the pages of a book written for them. Interestingly, the moralism of this very discussion also finds a material resonance in the fact that when we refer to “children’s literature” we refer, mostly, to books written by adults for children. Yes, in most children’s magazines, a few pages are “reserved” for children’s own creations. But, rarely do we use the term “children’s literature” to refer to literature created by children. In academic literary studies, texts created by children are often termed as juvenilia, thus, keeping the terrain of the creation of children’s literature reserved strictly for adults.

And, we conveniently forget, in the middle of it all, all children, much before they experience violence on the pages of a book meant for them, experience violence in real life. That violence often comes in the form of a quick slap, a sound scolding, an angry look, being force-fed. Incidentally, this is a kind of violence that we adults term as love. And indeed, they are, often, expressions of love. Yet, looking at such violence exclusively through the lens of love and caregiving also erases the fact that these are indeed acts of violence. In other words, there is a very core essence of adult-centricism in our efforts to erase the small but relentless incidences of violence that form the backbone of our adult love for children. The kind of violent love that forms the fulcrum of at least two social institutions we all vouch by – family and school. On the other hand, this also makes children privy to a strange knowledge. The knowledge that love and violence can reside within the same act. This is a form of knowledge for which we don’t give children enough credit. Hence, our efforts to moralize the very question of violence in children’s texts.

What I am also trying to point out here, creation of meaningful representations for children is a politically messy business. If the contemporary Hindu right’s educational and cultural projects targeted towards children are to be countered, we, who belong to the world of democratic and progressive social movements, need to think through the artistry and politics of such representations. What would progressive representations of childhood look like? It is a question that we, in the left, have often historically ignored. And, standing at the present historical juncture, this is precisely the question that we cannot afford to ignore. Not anymore.

To begin with, texts written for children are far from simple. The experience of childhood is far from simple. There is no childhood that exists outside of the inequalities that the adults have created. And, if there cannot be any such space where children can reside beyond the complex forms of social, economic and political inequality, moralizing about the presence of violence in children’s texts, becomes a futile exercise, at best.

As a writer and teacher, I am always looking for children’s books that can offer complex and well-done stories of childhood. Complex representations of childhood that would reveal to me the world a child resides in as a human being. Complex representations of childhood that would reveal to me the ways in which children are processing the social reality in contradictory ways. Complex representations of childhood that would show me, children can act as agents beyond adult intervention.

And, it is in the context of that quest that I first came across Rinchin, in a panel on art for children at the People’s Literary Festival, 2018 – in Kolkata. Rinchin divides her time between Chattisgarh and Madhya Pradesh. She happens to be an activist who works with people’s movements, and so far has written six books for children. Let me put it clearly. I was tempted to take a look into Rinchin’s oeuvre of work, precisely because I was interested to see what kinds of representations for children would an activist create.

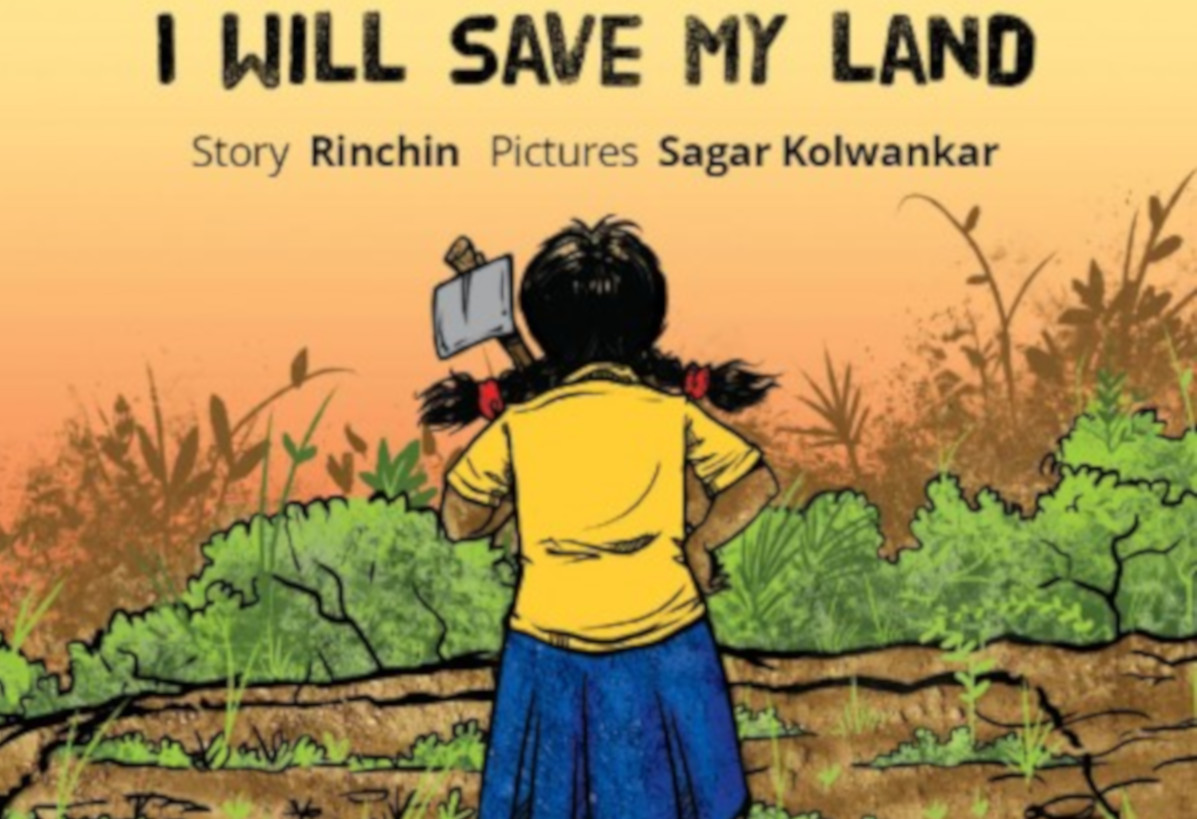

To begin with, Rinchin’s books are done well. The storylines are clear, yet complex. They always offer us complex representations of children – most often girls – who are involved in some quest or the other. For example, her The Trickster Bird and Sabri’s Colours. Most often, these girls happen to belong to marginalized communities in India, thus, prompting us to think of childhood as a category that exists beyond our middle-class protectionism and helicopter parenting. The illustrations in Rinchin’s books are exquisite, thus providing an additional layer of complexity for the young readers. Of all of Rinchin’s books, my own personal favorite is I Will Save My Land (2017). And, because this essay will have to be brief, it is that book of which I will provide a more in-depth reading in this essay.

I Will Save My Land begins from that premise that a concern over the presence of violence in children’s stories – I will repeat myself here– is at best a position that reeks of middle-class adult moralism. To begin with, the protagonist, Mati, is a daughter of the peasants, who, after school, works in the potato-fields of her family. In the fields, Mati can’t always carry the potato-basket, because it’s too heavy. She still doesn’t know how to use the spade. Her father warns her, that to use a spade without knowing how to use it, is to both risk getting oneself hurt, and spoil the crop. Here is, then, a child’s story that is already inextricably linked with agricultural labour. If back-breaking labour in the fields is a form of violence, then, an attempt to imagine Mati’s life without the presence of such violence is indeed fruitless.

Juxtaposed within the story of Mati’s life is also the story of her grandmother, who had fought to inherit her own land. A fight that was, the book tells us, as much against caste norms, as it was against the gendered norms of inheritance. In a dexterous use of a one-liner, the book reveals to the readers that Mati is not an upper-caste child. That line happens to be, “And since when have people from lower castes started to inherit land?” they [ie. The upper-caste villagers] wanted to know.”

Mati, too, dreams of her own land – the “doli” where she would work hard everyday after school. Yet, Mati’s story unfolds within a bigger story – a bigger story that is the story of her community, of contemporary India, of our contemporary globe. What is that story? A coal-mining company has been sending its representatives to the village to persuade the villagers to give up their land. That bigger story, then, happens to be one of land-grab. A story that in twenty-first century India has become one of the most potent forms of dispossessing communities and individuals of what rightfully belong to them. In other words, Mati’s story is implicated within the bigger story of “development.” The political narrative that the music video Gaon Chodab Nahi reminded us, turns villages like Mati’s, into our colonies. The colonies of the urban, elite folks.

In making the story of land-grab central to Mati’s story, then, the writer undertakes an interesting political move. If land-grab is one of the most important political realities in contemporary India, then, obviously, children cannot remain insulated from it. And, if children cannot remain insulated from bigger political realities, the latter also turns them into political subjects. Yes, that political subjectivity differs from adult political subjectivities. And, it is indeed difficult, as adults, to narrativize children’s political subjectivities. Yet, it is ultimately this difficult task that Rinchin attempts to bring through.

Rinchin. Photo courtesy: https://counterview.org/2017/07/14/sign-of-rising-state-repression-murder-of-land-rights-defenders-shoots-up-dramatically-in-india/

I Will Save My Land is ultimately the story of Mati’s evolving political subjectivity. To that end, Mati witnesses events that are crucial to anyone’s political growth – community meetings in the village, political gatherings, land already taken away to make space for the coal-mines, new friends. Yet, there is nothing special in these events that speak to the uniqueness of a child’s life or perspective. The uniqueness that is supposedly the special forte of children’s literature.

The book, then, begs for the question, what is it that makes certain books for children stick out? I would say, children’s rebellion. Children’s rebellion against adults. Children’s rebellion against the spaces within which adults confine them, supposedly for their own good. Consequently, most of the children’s rebellions occur against the backdrop of two significant institutions named earlier in the essay – the family and school. It is also a kind of rebellion that we adults term as disobedience. But, without some form of disobedience built into the plot, all children’s texts would fail to appeal to its audiences. Hence, the centrality of “naughty children” in almost all of classic children’s literature. Think Kanchan of Bari Theke Paliye. Think Pagla Dashu. Think Tom Sawyer. Think Huckleberry Finn. Yet, in almost every children’s book we have ever loved, the errant, rebellious, disobedient child is tamed. The truant child comes to accept and love the discipline of the school. The fleeing child is brought back home, within the boundaries of a domesticity, the norms of which have been determined by adults.

I Will Save My Land provides an interesting twist to this very notion of children’s rebellion on which the very formal structure of children’s texts are predicated. Mati, after all, belongs to a community which is engaged in a struggle against a mining company. In other words, big capital. As adult readers, we know, this is also a struggle that is bound to be a struggle against the state. In very conspicuous ways, then, the spectre of state violence, hangs over Mati’s head in a way that is difficult for most urban, middle-class readers to imagine. Within the pages of the book, that impending state violence is never spelt out. But, as adult readers, we know.

And, it is through this already-existing adult language about state violence, that Rinchin, as a writer, both engages with and side-steps the issue of direct representation of violence in children’s literature. There is no “direct” gory violence in I Will Save My Land, after all. But, then, Mati’s life cannot be understood without understanding the multi-layered forms of social violences within which it is implicated. No one gives her any respite because she is a child. And, this too, as adult readers, we know.

But, then, there is a bigger question of how to write a child’s rebellion in a world where one group of adults is at war with another. In Rinchin’s book, this essential anxiety is handled through a slight modification of the plot – by endowing upon Mati a kind of excess. An excess that establishes her as a child to the readers, but also narrativizes her unique political selfhood as a child within the pages of the book. Yes, Mati, much to the consternation of her father and grandfather, flees from her home.

A replication of the classic trope of the fleeing child of most children’s literature, Mati’s disappearance also raises a larger political question. What is Mati fleeing from, if she belongs, as it is, to a home and community, that is engrossed in a struggle against the corporate capital and state? Can such communities be oppressive to children too, even as they are fighting vital political struggles?

Rinchin’s book does not provide a clear-cut answer to such questions. Instead, the book subsumes the very question of children’s rebellion and agency into the larger question of the struggle against land-grab. This is achieved in the story, of course, through the very trope of the fleeing child, but Rinchin also recycles other classic tropes of children’s literature, while recasting them to suit her own purpose. When Mati disappears from her home, leaving her father and grandfather behind, she does not go for any random search for adventure. As it often happens in children’s adventure stories.

Instead, later at night, her grandmother finds her in the fields, sleeping, holding onto her little spade. Mati tells her grandmother, “I am saving my land.” In making her do so, Rinchin grants upon her a very specific kind of political subjectivity. Mati didn’t need any adult to tell her that she needs to save her land. Neither did she need any RSS volunteer to “protect” her from anything. Indeed, she possesses her own understanding of what needs to be done. What is more, she is willing to put her body on the ground for it. Literally.

Her grandmother responds, “We have to save our land. But now, come inside and sleep.” Like other children’s books, then, I Will Save My Land, too, writes the return of the child into the adult homestead. Yet, that return, operates only as a form of incomplete return — precisely because the community will have to return to the fields, the struggle against the land-grab is yet to begin. In that struggle, Mati’s presence, too, will be necessary. Her excess – represented in the book through her leaving of home – can be harnessed into something bigger. The child’s rebellion, for the moment, becomes one with the community’s rebellion – the adult rebellion, so to say – and thus, gains a kind of legitimacy within the book.

Even as we recognize the political relevance of such a move, we are prompted to ask, what kind of language and tropes will give equal primacy to both an autonomous children’s rebellion – against that ultimate form of tyranny that is the adult organization of the world – and socio-economic and political issues, within which the children are invariably implicated as members of specific class, caste, gender, racial or religious groups, and which need to be fought with adults. That language is yet to be born.

(Cover Image: Book cover for I Will Save My Land, Tulika 2017)

[…] is an activist based in Chattisgarh, and also a writer of fiction for children, in which capacity she was part of the first People’s Literary Festival last year, and joined […]